L’attenzione nei confronti di tutti i dettagli del vivere attuale esercita sugli artisti contemporanei una fascinazione alla quale è difficile sottrarsi, soprattutto perché è compito dei creativi lasciare una traccia dei tempi che vivono per poi consegnarli alle generazioni future; elaborare e interiorizzare le sensazioni, che poi vengono espresse in maniera impulsiva e disordinata, appartiene a chi sceglie lo stile informale tanto quanto descrivere e immortalare scorci di realtà, interpretabili sulla base della traccia che l’artista suggerisce ma anche sulla sensibilità e capacità di analisi dell’osservatore, è caratteristica di chi invece preferisce restare all’interno dello stile figurativo. Il protagonista di oggi si aggancia alla rappresentazione dell’osservato, scegliendo un mezzo inconsueto come l’acquarello per contraddistinguere la parte più consistente della sua produzione, ma poi si spinge verso l’immaginazione per andare a indagare i sogni nascosti, le energie sottili non evidenti eppure in grado di emergere e avvolgere la realtà e che può risultare visibile solo a chi resta legato a una sensibilità attraverso cui riesce ad andare oltre.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte più recente, quella tra la fine del Diciannovesimo e l’inizio del Ventesimo secolo, si è assistito a un tipo di approccio bivalente nei confronti della pittura, o forse sarebbe meglio dire della rappresentazione del visibile, poiché una volta abbandonata la tendenza al ritratto commissionato dai nobili e dalle famiglie più abbienti, alcuni artisti hanno cominciato a porre maggiore attenzione alle persone più umili, ai lavoratori, a una classe operaia o contadina il cui lavoro produceva ricchezza per i proprietari terrieri o per quelli delle nuove fabbriche della produzione in serie. Dunque il Realismo di metà Ottocento mise in evidenza, con Gustave Courbet e Jean-François Millet, gli scorci di vita quotidiana del popolo, della gente comune povera e senza speranza di affrancarsi dal loro destino; con il proseguire degli anni e il sopraggiungere del Novecento l’accezione iniziale di osservazione si trasformò in denuncia, con il Muralismo di Diego Rivera o le lotte di classe di cui il Terzo stato di Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo fu il simbolo, e incitazione alla rivalsa, alla presa di coscienza da parte del popolo della propria forza. Parallelamente si stava però concretizzando una declinazione dello stile che da un lato tese verso il mistero, l’enigma esistenziale che ebbe la sua manifestazione nel Realismo Magico, mentre dall’altro, in un periodo in cui l’urgenza di alzare la testa e combattere per condizioni migliori si era affievolita, si concentrò sulle sensazioni dell’individuo, nelle emozioni e nella solitudine percepita malgrado il benessere ottenuto o a dispetto del trovarsi in mezzo a una folla. Il Realismo Americano, in particolar modo con Edward Hopper nelle sue silenziose atmosfere notturne cittadine o dei sobborghi in cui viveva l’emergente classe media e con George Bellows che invece era molto più ammaliato dalla vita nelle strade e dal rumore di tutta la moltitudine di persone che abitava le metropoli, riuscì a lasciare un interessante scorcio sulla società statunitense di inizio secolo. In entrambi i movimenti, il Realismo Magico e il Realismo Americano, mancava tuttavia quell’attenzione verso la fantasia, l’immaginazione, la capacità di porsi in ascolto di tutto ciò che pur non essendo chiaramente visibile era in ogni caso presente, sotto la linea inavvertibile della percezione.

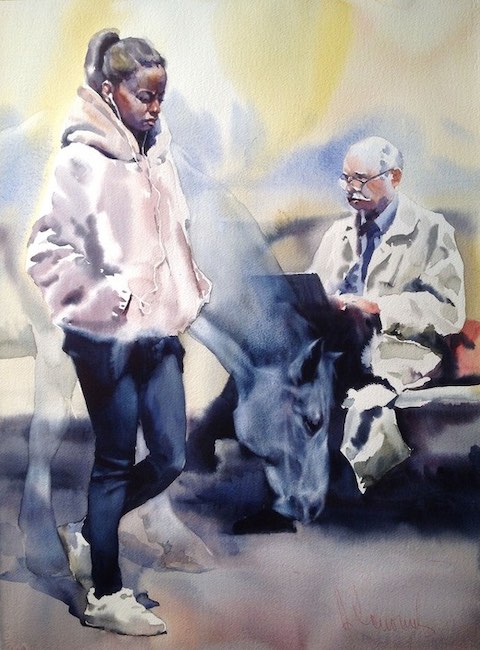

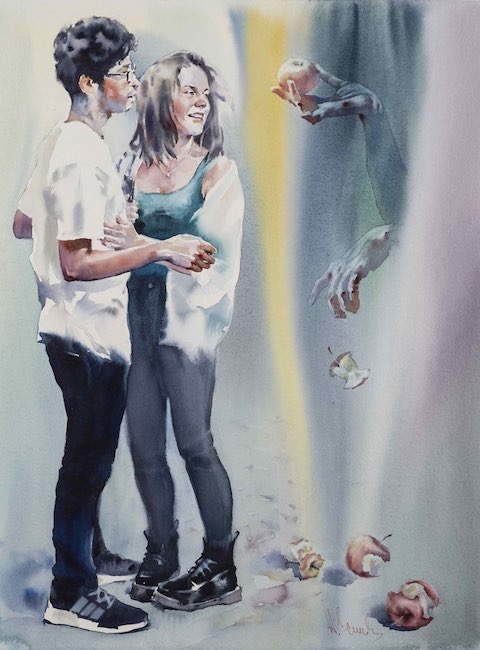

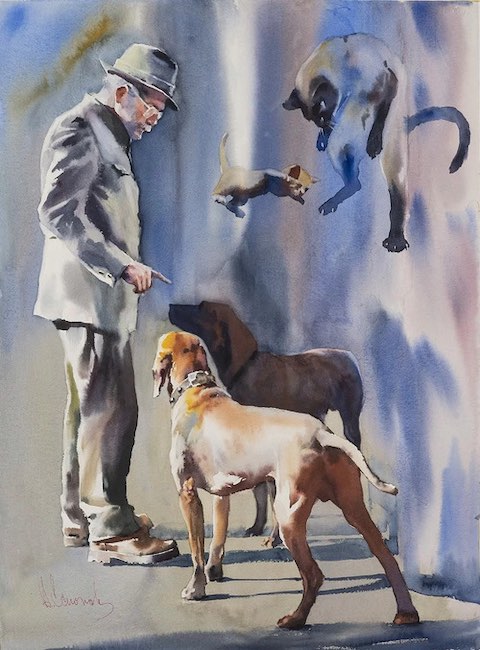

L’artista uzbeko Andrey Esionov crea un ponte in cui l’osservazione di tutto ciò che appartiene alla realtà moderna e al vivere contemporaneo, viene sovrapposto come in una dimensione magica al lato immaginario, al sentire spesso consapevole ma molte altre volte inconsapevole, di quelle sensazioni, quelle dimensioni a metà tra presente e passato che pervadono e accompagnano ogni gesto, ogni azione della quotidianità; le sue opere in acquarello, usato però in maniera definita e al tempo stesso evanescente proprio nella parte in cui l’artista descrive la dimensione immaginaria, raccontano la vita delle città piena di persone che camminano, si muovono, viaggiano, dando rilevanza al fare piuttosto che all’essere e dunque di frequente distratte da una contingenza che impedisce loro di connettersi con l’interiorità, quell’anima che percepisce il disagio di non potersi esprimere e così aleggia sui personaggi come avesse una propria personalità. Il Realismo Visionario è lo stile a cui Esionov appartiene, quello a cui di fatto ha dato origine per la sua capacità di mettere in luce il non detto, il sussurrato, la realtà parallela che talvolta emerge mentre altre tende a nascondersi agli attori principali diventando però evidente a chi, come lui, osserva tutto dal di fuori della scena.

Il suo talento nel disegno si sposa pertanto con una particolare capacità di dosare sapientemente l’acquarello, distinguendo la parte vissuta da quella fantastica che tuttavia riesce a emergere in maniera consistente, come se il suo essere quasi dissolta negli sfondi o in tutto ciò che si trova dietro di essa contribuisse a farla fuoriuscire in maniera persino più netta.

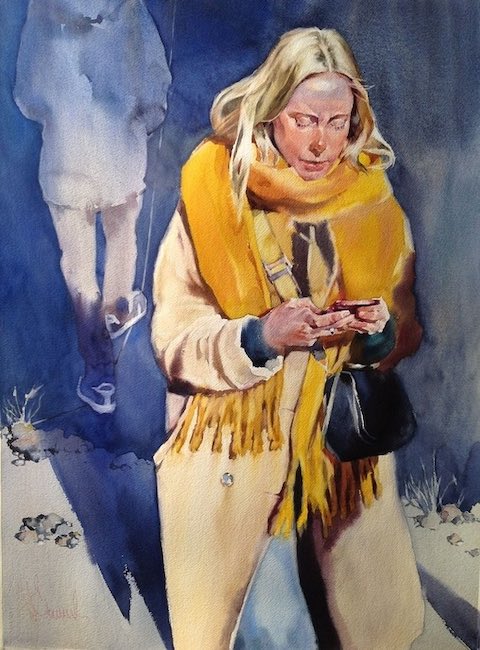

Ma ciò che più colpisce di Andrey Esionov è la maestria nel descrivere con leggerezza le caratteristiche umane, osservando, entrando in empatia e a volte criticando sottilmente tutto ciò che appartiene al mondo attuale e che genera un eccessivo individualismo, un attaccamento agli oggetti ma un distacco dalle persone che si incrociano quotidianamente.

È proprio a questo che è dedicata l’opera Empathic blindness in cui una giovane donna è talmente concentrata a controllare il suo cellulare da non riuscire a sollevare lo sguardo perdendosi il bello dell’ambiente che la circonda, dell’uomo che incrocia e che potrebbe aver avuto il desiderio semplice e spontaneo di salutarla o di sorriderle; lei però pensa solo al messaggio da leggere, a quella tecnologia che ormai è talmente parte della vita di ogni giorno da aver assorbito l’attenzione e la concentrazione, perché forse è più facile scrivere una frase a effetto piuttosto che confrontarsi faccia a faccia, lasciando fluire le emozioni e dedicando del tempo all’interazione. La presenza della donna appare forte e ben definita, eppure c’è qualcosa che la fa sembrare anche fragile, forse proprio la sua incapacità di sollevare lo sguardo scegliendo di essere se stessa, senza nascondersi dietro lo schermo di un cellulare che permette di celare le proprie emozioni.

Nel lavoro Absolut rumor la violoncellista si distrae dalla sua musica al punto di voler dare voce ai manichini di una vetrina, come se l’arco con cui abitualmente fa fuoriuscire note dallo strumento si trasformasse in una bacchetta magica in grado di dar vita a ciò che non ne ha, di esortare chi abitualmente si occupa solo della forma esteriore ad approfondire e curare anche il lato sostanziale. In qualche modo l’opera è una metafora del vivere contemporaneo, di una società troppo preoccupata di correre dietro all’effimero che non lascia testimonianza del suo passaggio una volta che gli abiti verranno gettati e che il corpo affronterà il decadimento dovuto all’età. Dunque la musicista, di fatto un’artista, sembra suggerire a quegli esangui manichini di risvegliarsi dal torpore, di cominciare a vivere intensamente l’esistenza coltivando l’anima e tutto ciò che può costituire un valore aggiunto, una consistenza dell’essere che ha bisogno di nutrirsi di altro rispetto alla pura apparenza.

In No fate Esionov, profondo osservatore dei dettagli metropolitani, immortala delle donne comuni mentre siedono nella stessa panchina in cui un artista di strada, probabilmente autore della scritta che dà il titolo all’opera, ha lasciato le bombolette spray, quasi incuranti che proprio in quello scorcio urbano si è consumata la manifestazione di un pensiero, di una critica verso la società attuale impegnata a celebrare chi già ha possibilità economiche e dunque un fiorente futuro già scritto, lasciando indietro con indifferenza che invece un domani diverso vorrebbe scriverlo, o guadagnarselo. I volti delle donne infondono nell’osservatore la sensazione di far parte di quel gruppo di dimenticati, di chi sopravvive senza avere un vero senso nella vita, senza essere in grado di uscire da quell’ombra fatta di giorni tutti uguali a se stessi dove l’unico svago è sedersi su una panchina e parlare dei propri piccoli drammi, delle insoddisfazioni che non riescono a non permeare la loro esistenza.

La capacità di Andrey Esionov di guardarsi intorno andando a cercare tutto quel sottile che a uno sguardo superficiale sfugge costituisce la caratteristica principale del suo Realismo Visionario, così come la gamma cromatica evanescente ma al contempo reale esalta il lato immaginario della sua osservazione sul mondo contemporaneo. Andrey Esionov è maestro di acquarello, disegno e pittura, le sue opere fanno parte di musei in Russia – Mosca e San Pietroburgo – in Tatarstan, in Uzbekistan e in Italia, e ha al suo attivo mostre personali e collettive.

ANDREY ESIONOV-CONTATTI

Email: andrey@esionov.ru

Sito web: https://esionov.ru/en/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Esionov

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/esionov_italy/

The Visionary Realism of Andrey Esionov, between metropolitan lives and the lack of perception of an invisible that nevertheless exists

Attention to all the details of modern life exerts a fascination on contemporary artists that is difficult to escape, especially since it is the task of creative artists to leave a trace of the times they live in order to hand them down to future generations; elaborating and internalising sensations, which are then expressed in an impulsive and disorderly manner, belongs to those who choose the informal style just as much as describing and immortalising glimpses of reality, which can be interpreted on the basis of the trace that the artist suggests but also on the observer’s sensitivity and capacity for analysis, is characteristic of those who prefer to remain within the figurative style. Today’s protagonist latches onto the representation of the observed, choosing an unusual medium such as watercolour to distinguish the most consistent part of his production, but then pushes towards the imagination to investigate hidden dreams, the subtle energies that are not evident yet able to emerge and envelop reality and that can only be visible to those who remain bound to a sensibility through which they are able to go beyond.

In the course of more recent art history, that between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, there has been a kind of bivalent approach to painting, or perhaps it would be better to say to the representation of the visible, as once the tendency towards portraits commissioned by the nobility and wealthy families had been abandoned, some artists began to pay more attention to the humblest people, to workers, to a working class or peasant class whose labour produced wealth for landowners or for those in the new factories of mass production. Thus, mid-nineteenth-century Realism emphasised, with Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, the glimpses of the everyday life of the people, of poor ordinary people with no hope of freeing themselves from their fate; as the years went on and the 20th century arrived, the initial meaning of observation turned into denunciation, with the Muralism of Diego Rivera or the class struggles of which Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo‘s The Third Estate was the symbol, and incitement to revenge, to the people’s awareness of their own strength. At the same time, however, a declination of style was taking shape, which on the one hand tended towards mystery, the existential enigma that had its manifestation in Magic Realism while on the other hand, at a time when the urge to raise one’s head and fight for better conditions had waned, it focused on the individual’s feelings, emotions and perceived loneliness in spite of the affluence achieved or in spite of being in a crowd.

American Realism, especially with Edward Hopper in his silent nocturnal city or suburban atmospheres in which the emerging middle class lived, and with George Bellows who was much more fascinated by life in the streets and the noise of the multitude of people inhabiting the metropolises, managed to leave an interesting insight into American society at the turn of the century. However, both movements, Magic Realism and American Realism, lacked that attention to fantasy, imagination, the ability to listen to everything that although not clearly visible was nevertheless present, beneath the unnoticeable line of perception. The Uzbek artist Andrey Esionov creates a bridge in which the observation of everything that belongs to modern reality and contemporary living is superimposed, as if in a magical dimension, on the imaginary side, on the often conscious but many times unconscious feeling of those sensations, those dimensions somewhere between the present and the past that pervade and accompany every gesture, every action of daily life; his artworks in watercolour, used in a defined and at the same time evanescent manner precisely in the part where the artist describes the imaginary dimension, tell the story of city life full of people walking, moving, travelling, giving importance to doing rather than being and therefore frequently distracted by a contingency that prevents them from connecting with their interiority, that soul that perceives the discomfort of not being able to express itself and thus hovers over the characters as if it had a personality of its own.

Visionary Realism is the style to which Esionov belongs, the one to which he in fact gave rise because of his ability to highlight the unspoken, the whispered, the parallel reality that sometimes emerges while at others tends to hide from the main actors but becomes evident to those who, like him, observe everything from outside the scene. His talent in drawing is therefore combined with a particular ability to skillfully dose watercolour, distinguishing the lived part from the fantastic part, which nevertheless manages to emerge consistently, as if its being almost dissolved in the backgrounds or in everything behind it contributes to making it stand out even more clearly. But what is most striking about Andrey Esionov is his mastery in lightly depicting human characteristics, observing, empathising with and sometimes subtly criticising everything that belongs to today’s world and that generates excessive individualism, an attachment to objects but a detachment from the people one encounters on a daily basis. It is precisely to this that is dedicated the artwork Empathic blindness, in which a young woman is so concentrated on checking her mobile phone that she is unable to lift her gaze, missing the beauty of her surroundings, of the man she crosses and who may have had the simple and spontaneous desire to greet her or smile at her; she, however, thinks only of the message to be read, of the technology that is now so much a part of everyday life that it has absorbed her attention and concentration, because perhaps it is easier to write a catchphrase than to confront each other face to face, letting emotions flow and devoting time to interaction.

The woman’s presence appears strong and well-defined, yet there is something that also makes her seem fragile, perhaps her inability to lift her gaze and choose to be herself, without hiding behind the screen of a mobile phone that allows her to conceal her emotions. In the artwork Absolut rumor, the cellist distracts herself from her music to the point of wanting to give voice to the mannequins in a shop window, as if the bow with which she habitually lets out notes from the instrument were transformed into a magic wand capable of giving life to what has none, of exhorting those who habitually deal only with the exterior form to also deepen and take care of the substantial side. In a way, the work is a metaphor for contemporary living, of a society too preoccupied with running after the ephemeral that leaves no evidence of its passing once the clothes are thrown off and the body faces the decay due to age. So the musician, in fact an artist, seems to be suggesting to those lifeless mannequins to awaken from their torpor, to begin to live existence intensely by cultivating the soul and everything that can constitute an added value, a consistency of being that needs to be nourished by something other than pure appearance.

In No Fate, Esionov, a profound observer of metropolitan details, immortalises ordinary women as they sit on the same bench where a street artist, probably the author of the work that give its title to the watercolor, has left his spray cans, almost oblivious to the fact that it is in that very urban setting that a thought has taken place, of a critique of today’s society committed to celebrating those who already have economic possibilities and thus a flourishing future already written, leaving behind with indifference those who would instead like to write or earn a different tomorrow. The women’s faces instil in the observer the sensation of being part of that group of forgotten, of those who survive without having any real meaning in life, without being able to come out of that shadow made up of days all the same where the only entertainment is to sit on a bench and talk about their own little dramas, the dissatisfactions that cannot fail to permeate their existence. Andrey Esionov‘s ability to look around for all that subtlety that escapes a superficial glance constitutes the main characteristic of his Visionary Realism, just as the evanescent yet real colour palette enhances the imaginary side of his observation of the contemporary world. Andrey Esionov is a master of watercolour, drawing and painting, his works are part of museums in Russia – Moscow and St Petersburg – in Tatarstan, Uzbekistan and Italy, and he has solo and group exhibitions to his credit.