L’osservazione del mondo circostante viene a volte ammantato e arricchito dallo sguardo sensibile dell’artista che sceglie di immortalarlo, lasciando che le proprie vibranti corde interiori interpretino il visibile attraverso il filtro della capacità di ascolto, che comincia con gli occhi ma si sposta poi in fondo all’interiorità; ciascun creativo dona all’osservatore la propria interpretazione, a volte più mentale e filosofica, altre più morbida e poetica, sempre però esplorativa di ciò che ruota intorno e che troppo spesso tende a restare invisibile. Il protagonista di oggi ha la singolare capacità di riuscire a carpire il momento più intimo dei personaggi ritratti, entrando in connessione con il loro sentire e narrandolo in virtù del suo.

Il legame tra Surrealismo e Metafisica è stato sempre piuttosto sottile, malgrado il fondatore del secondo, Giorgio De Chirico, si sia sempre dichiarato distante, se non opposto, alle tematiche del primo; eppure il senso di mistero, quell’enigma mai svelato che nell’uno apparteneva al rapporto dell’uomo con il passato e alla capacità di accettare un’esistenza di cui è impossibile spiegare il senso, legandosi per questo a oggetti che a loro volta emanano energia proprio in virtù della loro immobile familiarità, mentre nell’altro si lega ai sogni, agli incubi, alle angosce della mente che tendono a materializzarsi nel mondo onirico, o alle inquietudini esistenziali che mettono in discussione le certezze interiori e quelle esterne. I maggiori rappresentanti delle due parallele correnti artistiche, Salvador Dalì, Yves Tanguy per il Surrealismo e Giorgio De Chirico e Carlo Carrà per la Metafisica, furono fortemente legati alla loro epoca, quegli inizi del Novecento che lasciarono una traccia profonda nella storia dell’arte e che nel tempo hanno subìto interpretazioni e rivisitazioni e che non hanno mai smesso di essere di ispirazione per i successivi decenni e ancora nel nostro secolo. In particolar modo René Magritte, un oustider che si è mosso costantemente sulla linea di confine tra i due movimenti, ha saputo interpretare magistralmente il mistero enigmatico dei luoghi apparentemente familiari eppure completamente decontestualizzati e al tempo stesso le inquietudini, le incertezze dell’uomo dell’epoca ponendo l’essere umano, costantemente assente nelle linee guida della pura Metafisica, al centro della sua ricerca. Lentamente dunque, nell’evoluzione successiva, l’apertura del maestro belga alla contaminazione delle due correnti coeve, diede vita a un nuovo modo di immettere l’esistenzialismo filosofico nella pittura metafisica che sfociò nel Realismo magico di Felice Casorati in cui la staticità dei personaggi rappresentati, il senso di solitudine e gli sguardi malinconici ma calmi, emanavano un senso di introspezione, di analisi e di meditazione in grado di indurre l’osservatore a riflettere su se stesso e sul senso profondo della vita. Si colloca esattamente in questo contesto, in questa terra di mezzo tra Metafisica e Realismo Magico, lo stile pittorico dell’artista romano Antonio Ricci che riesce a cogliere l’attimo più intimo, più meditativo o rappresentativo di un particolare frangente dei personaggi raccontati, di quegli uomini e quelle donne che si mettono in contatto con la loro essenza più profonda, prendono atto della propria instabilità, della loro solitudine la quale, agli occhi sensibili dell’artista, diviene istante lirico di silenziosa intensità.

Il tocco pittorico è realista eppure il suo sguardo non riesce a soffermarsi sull’apparenza, ha bisogno di andare oltre, di scavare nella mente e nelle emozioni dei suoi protagonisti, persone comuni e tuttavia straordinarie nella loro unicità, uomini, donne, anziani, bambini che perdono, oppure cercano di ritrovare, il senso di un’esistenza che troppo spesso corre via veloce, senza lasciare loro il tempo di prendere atto degli eventi, del suo scorrere, della necessità di guardarsi dentro prima che sia troppo tardi.

Emerge spesso il senso di nostalgia dalle tele di Ricci, quel legame con il passato che costituisce la base del presente, sia che sia stato positivo sia che invece abbia provocato ferite e cicatrici a causa delle quali il frangente attuale appare complesso, incerto, insoddisfacente; i protagonisti sono soventemente ripiegati su se stessi, come a proteggere la propria delicata interiorità o a raccogliere le idee, le emozioni, i ricordi dai quali è difficile prescindere, tanto quanto è impossibile dimenticare, malgrado la tendenza precedente a lasciarli in un angolo nascosto.

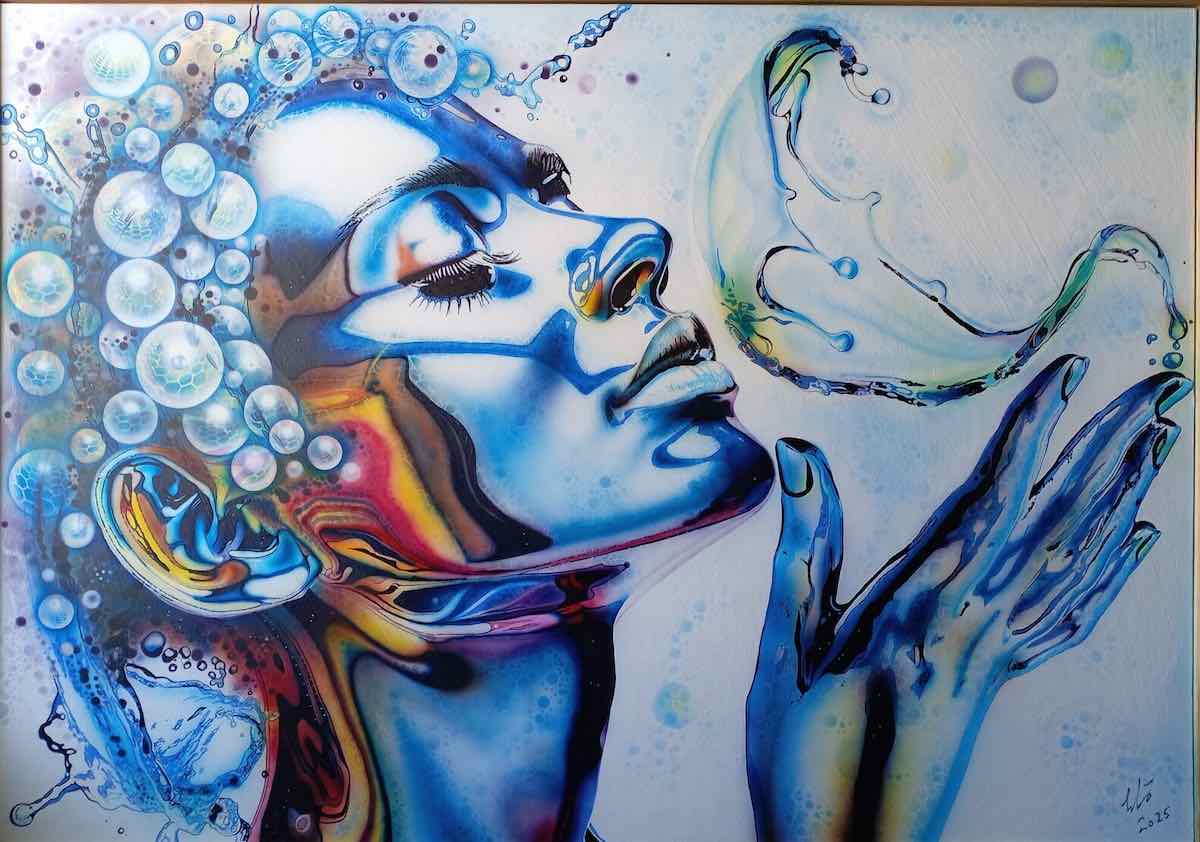

L’opera Associazioni armoniche descrive un momento di solitudine interiore, l’esigenza della protagonista di mettersi a nudo e di entrare in profonda connessione con le proprie sensazioni più nascoste, quelle che fino a un attimo prima ha fatto fatica ad ammettere persino con se stessa ma che poi non possono fare a meno di travolgerla inducendola a prendere atto della loro intensità. L’atmosfera con cui Antonio Ricci circonda il corpo della donna è morbida, carezzevole e sospende il tempo e lo spazio, come se ogni elemento fosse funzionale all’istante raccontato, allo stato d’animo del personaggio femminile narrato; le tonalità sono sfumate, quasi irreali, perché la luce che illumina il corpo è quella soffusa dell’alba per armonizzarsi con il risveglio di consapevolezza, vero protagonista della tela.

In Equilibrio instabile 3, al contrario, le tonalità sono più cupe, quasi a sottolineare il timore della donna, quasi ad accrescere il senso di disagio interiore che non le permette di trovare all’internò di sé quel bilanciamento a cui tende; l’espressione del volto è contratta, avvilita e dispiaciuta per non essere in grado di prendere atto delle proprie umane debolezze impedendo così a se stessa di accogliere e accettare ciò che non può essere cambiato. Solo attraverso l’ammissione dei propri punti di forza e della propria fragilità, senza combattere contro di essa, è possibile raggiungere quell’evoluzione che la indurrà a non temere più la caduta, l’incapacità di rialzarsi o di restare in piedi sulle proprie gambe; la gamma cromatica qui è più nitida, meno sfumata, come se l’artista volesse esortare la sua protagonista a effettuare quel passaggio verso una maggiore autocoscienza, ad abbandonare l’instabilità di una base, quella della sfera, che è solo un’illusione di equilibrio per andare verso un’accresciuta sicurezza di sé.

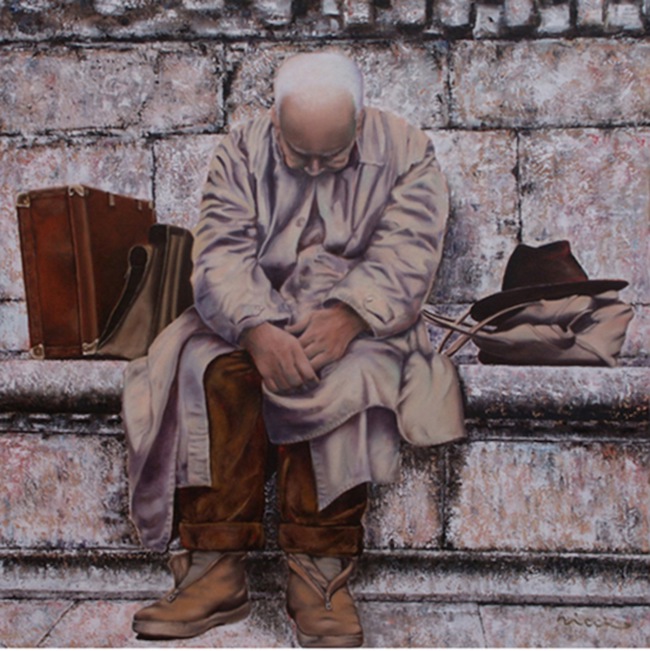

Nelle opere di Ricci la positività è sempre presente, a volte più sottintesa e altre più evidente come nell’opera Bisogna avere speranza in cui un tenero anziano allevia la sua solitudine nutrendo le colombe, lasciandosi avvolgere dalla loro delicatezza e cercando un silenzioso dialogo con quelle creature innocenti da proteggere tanto quanto sa che a sua volta vorrebbe sentirsi protetto durante l’ultimo percorso della sua esistenza; la luna e le stelle infondono quell’atmosfera poetica che contraddistingue l’intera produzione artistica di Antonio Ricci, quella capacità straordinaria di accordare i colori e le immagini allo stato d’animo non solo dei suoi personaggi, bensì anche a quello dell’osservatore che non può non sentirsi coinvolto dalle sensazioni che la tela emana.

Anche in All the love can do, opera esposta presso la Love Art Gallery di Palo Alto Hills, San Francisco, l’artista infonde la speranza, quel soffio delicato di positività e di buoni sentimenti che possono deviare il corso della storia, ammorbidire la durezza di posizioni che generano conflitti, guerre, distruzione; la scelta di rappresentare le armi in mano ai bambini costituisce una domanda all’osservatore, “vogliamo davvero lasciare questo futuro ai nostri figli?”, la cui risposta viene data da una coetanea, da una bambina che sembra tendere la mano richiamando l’attenzione su un’innocenza che non deve essere perduta e che può ancora trasformare la crudezza in amore, come il titolo evoca. Antonio Ricci è membro dell’Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta, con cui espone regolarmente, le sue opere sono inserite all’interno di importanti riviste d’arte e alcune sono in esposizione permanente presso la Pinacoteca della Galleria d’Arte Stomeo di Marzano (LE), presso la pinacoteca della Facoltà di Belle Arti di Luxor in Egitto, e nel Museo Civico d’Arte Contemporanea MAGMA di Roccamorfina (CE).

ANTONIO RICCI-CONTATTI

Email: antonricci@alice.it

Sito web: www.antonioricciartista.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/antonio.ricci.35574

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/antonio-ricci-50080233/

Antonio Ricci, when Metaphysics marries silence and turns into poetry

Observation of the surrounding world is sometimes cloaked and enriched by the sensitive gaze of the artist who chooses to immortalise it, letting his own vibrant inner chords interpret the visible through the filter of his ability to listen, which begins with the eyes but then moves deep into the interiority; each creative artist gives the observer his own interpretation, sometimes more mental and philosophical, sometimes softer and more poetic, but always exploratory of what revolves around and all too often tends to remain invisible. Today’s protagonist has the singular ability to capture the most intimate moment of the characters portrayed, connecting with their feelings and narrating them by virtue of his own ones.

The link between Surrealism and Metaphysical Art has always been rather thin, despite the fact that the founder of the latter, Giorgio De Chirico, always declared himself distant from, if not opposed to, the themes of the former; nd yet the sense of mystery, that never revealed enigma which in the one belonged to man’s relationship with the past and the capacity to accept an existence whose meaning it is impossible to explain, thus binding him to objects that in turn emanate energy precisely by virtue of their immobile familiarity, while in the other it is linked to dreams, nightmares, the anxieties of the mind that tend to materialise in the dream world, or to existential restlessness that calls into question inner and outer certainties. The greatest representatives of the two parallel artistic currents, Salvador Dali and Yves Tanguy for Surrealism and Giorgio De Chirico and Carlo Carrà for Metaphysical Art, were strongly linked to their era, those early twentieth-century periods that left a deep mark on the history of art and that over time have undergone interpretations and reinterpretations and have never ceased to be an inspiration for the following decades and still in our century. In particular, René Magritte, an oustider who constantly moved along the borderline between the two movements, was able to masterfully interpret the enigmatic mystery of apparently familiar yet completely decontextualised places and at the same time the anxieties and uncertainties of the man of the time, placing the human being, constantly absent from the guidelines of pure Metaphysics, at the centre of his research.

Slowly, therefore, the Belgian master’s openness to the contamination of the two contemporary currents gave rise to a new way of introducing philosophical existentialism into metaphysical painting, which culminated in Felice Casorati’s Magic Realism in which the static nature of the characters depicted, the sense of solitude and the melancholic but calm gaze emanated a sense of introspection, analysis and meditation capable of inducing the observer to reflect on himself and on the profound meaning of life. It is exactly in this context, in this middle ground between Metaphysics and Magic Realism, that the painting style of the Roman artist Antonio Ricci is placed. He succeeds in capturing the most intimate, most meditative or representative moment of a particular juncture of the characters told, of those men and women who get in touch with their deepest essence, take note of their instability, of their solitude which, to the sensitive eyes of the artist, becomes a lyrical instant of silent intensity. The artist’s pictorial touch is realistic, yet his gaze cannot dwell on appearances; it needs to go beyond them, to delve into the minds and emotions of his protagonists, ordinary people who are nonetheless extraordinary in their uniqueness, men, women, elderly people and children who lose, or try to find again, the meaning of an existence that all too often rushes by, leaving them no time to take note of events, of its passing, of the need to look inside themselves before it is too late. A sense of nostalgia often emerges from Ricci’s canvases, that link with the past which constitutes the basis of the present, whether it has been positive or has caused wounds and scars because of which the present situation appears complex, uncertain and unsatisfactory; the protagonists are often withdrawn into themselves, as if to protect their own delicate interiority or to collect ideas, emotions and memories from which it is difficult to prescind, just as it is impossible to forget, despite the previous tendency to leave them in a hidden corner.

The work Harmonic Associations describes a moment of inner solitude, the protagonist’s need to lay herself bare and to enter into a deep connection with her most hidden feelings, those which until a moment before she found it difficult to admit even to herself but which then could not help overwhelming her, inducing her to take note of their intensity. The atmosphere with which Antonio Ricci surrounds the woman’s body is soft, caressing and suspends time and space, as if every element were functional to the instant narrated, to the state of mind of the female character narrated; the tones are shaded, almost unreal, because the light that illuminates the body is the soft light of dawn, harmonising with the awakening of awareness, the true protagonist of the canvas. In Equilibrio instabile 3, on the other hand, the tones are darker, almost as if to underline the woman’s fear, almost as if to increase her sense of inner unease that does not allow her to find the balance within herself that she is striving for; the expression on her face is contracted, disheartened and sorry for not being able to acknowledge her own human weaknesses, thus preventing herself from accepting what cannot be changed. Only by admitting her own strengths and weaknesses, without fighting against them, is it possible to achieve the kind of evolution that will lead her to stop fearing the fall, the inability to get up or to stand on her own two feet; the chromatic range here is sharper, less blurred, as if the artist wanted to urge his protagonist to make that transition towards greater self-awareness, to abandon the instability of a base, that of the sphere, which is only an illusion of balance in order to move towards greater self-confidence. Positivity is always present in Ricci’s artworks, sometimes more subtly and sometimes more clearly, as in the work Bisogna avere speranza (We must have hope) in which a tender old man relieves his loneliness by feeding the doves, letting himself be enveloped by their delicacy and seeking a silent dialogue with these innocent creatures to be protected as much as he knows that he in turn would like to feel protected during the last stage of his existence; the moon and the stars infuse that poetic atmosphere that distinguishes Antonio Ricci’s entire artistic production, that extraordinary ability to tune colours and images to the mood not only of his characters, but also to that of the observer, who cannot help but feel involved in the sensations emanating from the canvas.

In All the love can do, a work exhibited at the Love Art Gallery in Palo Alto Hills, San Francisco, the artist also instils hope, that delicate breath of positivity and good feelings that can divert the course of history, soften the harshness of positions that generate conflicts, wars and destruction; the choice to represent weapons in the hands of children is a question to the observer, “do we really want to leave this future to our children?” awhose answer is given by a girl of the same age, a little girl who seems to hold out her hand, drawing attention to an innocence that must not be lost and that can still transform crudity into love, as the title evokes. Antonio Ricci is a member of the Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta, with which he exhibits regularly. His artworks are included in important art magazines and some of them are on permanent display at the Pinacoteca of the Galleria d’Arte Stomeo in Marzano (LE), at the art gallery of the Faculty of Fine Arts in Luxor, Egypt, and at the Museo Civico d’Arte Contemporanea MAGMA in Roccamorfina (CE).