L’esigenza di attingere al passato più recente per disegnare uno stile personale attraverso il quale poter esprimere sensazioni profonde pur adattandole a una vita moderna completamente differente dalle radici a cui ispirarsi, è caratteristica distintiva di molti artisti che vivono e operano nei tempi attuali, approfittando del privilegio di aver potuto studiare quei rivoluzionari maestri del Novecento avendo così la possibilità di rielaborare le loro intuizioni espressive mescolandole e fondendole nella piena libertà che contraddistingue l’arte del Ventunesimo secolo. L’artista di oggi presenta esattamente questa peculiarità incrementata e accresciuta dalle sue radici familiari miste che le hanno sempre fatto percepire la positività e il valore dell’unione tra culture diverse inducendola ad applicare questo valore anche alle sue opere.

Il periodo storico a cavallo tra la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo e l’inizio del Ventesimo fu segnato da una serie di rivoluzioni pittoriche e scultoree destinate a rompere gli schemi precedenti, legati al Realismo e alla necessità di attenersi alle regole accademiche, e ad affermare con forza sia la necessità di mettere in primo piano l’interiorità dell’artista sia l’esigenza di libertà di sperimentare e sovvertire quei dogmi che fino a poco prima era inimmaginabile rompere senza essere esclusi dai salotti culturali che contavano. Tra i vari movimenti di quell’epoca ne emerse uno che investì nazioni europee differenti per storia artistica ma che si trovarono ad aderire con entusiasmo e forte spinta creativa alle proposte degli ideatori di un nuovo modo di concepire un’opera, includendo al suo interno anche tecniche artigiane ed estendendo la creatività a campi fino a poco prima assolutamente inesplorati. L’Art Nouveau, che in Italia prese il nome di Stile Liberty, in Spagna si chiamò Modernismo, in Inghilterra Arts and Crafts e in Austria Secessionismo Viennese, fu forse il primo a stabilire l’importanza delle arti applicate, dell’artigianato come risultato del lavoro dell’uomo che doveva contrapporsi all’industrializzazione spersonalizzante del periodo, estendendo le possibilità creative ai vetri, ai metalli, ai tappeti, e introducendo le tecniche decorative alla pittura che ancora manteneva un raffinato gusto estetico di forte impatto e di fascino sontuoso. Le opere di Gustav Klimt, maggiore esponente del Secessionismo Viennese, hanno tracciato un cammino che però è rimasto limitato alla sua genialità ed è entrato in contrasto con un’altra innovativa corrente pittorica, l’Espressionismo, che al contrario si imponeva di rinunciare completamente all’estetica per privilegiare l’emozione, le sensazioni intense, anche se questo significava rinunciare alla bellezza, all’attinenza a una realtà osservata che spesso non era affine all’interiorità necessitante di fuoriuscire. Fu proprio dalle ceneri della rivoluzione del Secessionismo che proprio Vienna vide la nascita di uno dei più grandi maestri dell’Espressionismo, Egon Schiele, il quale fece della bruttezza e della deformità dei corpi narrati la sua linea creativa, perché ciò che doveva emergere era il disagio esistenziale, le paure dell’animo che potevano essere placate e rassicurate con la sessualità. L’artista greca Sophie Iakovidi si avvicina spontaneamente allo stile dei due grandi maestri dei primi del Novecento in virtù delle sue origini miste greco-austriache che la spingono verso la sperimentazione, la comunicazione tra linguaggi apparentemente separati eppure in qualche modo conciliabili proprio in virtù di quella libertà espressiva che caratterizza l’epoca contemporanea e che le consente di cercare una propria cifra stilistica al contempo originale ma anche legata a quelle radici storiche che infondono ispirazione e conoscenza.

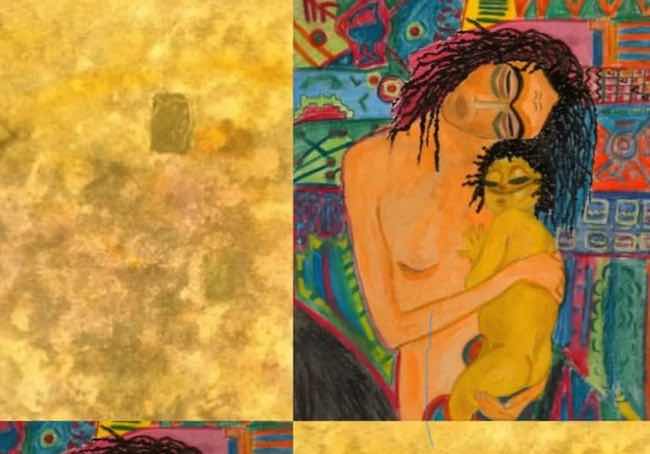

Da un lato le sue tele tendono verso il Secessionismo Viennese ispirato a Klimt, con un ampio utilizzo della foglia oro e delle tonalità auree che avvolgono i suoi personaggi, spesso delicatamente reclinati per esprimere dolcezza e intensità emozionale, dall’altro tendono verso l’Espressionismo, in alcuni dipinti vicino a quello di Schiele, di cui mantiene l’intensità espressiva e la tendenza all’interiorizzazione di un’emozione, di una sensazione o di un punto di vista sull’osservato che viene filtrato e reinterpretato dalla sua sensibilità e che giunge in modo diretto e immediato all’osservatore.

Ciò che emerge in maniera evidente è la delicatezza con cui Sophie Iakovidi affronta le emozioni, quasi con una discrezione che la induce a rispettare i suoi protagonisti, senza rivelarne più di quanto non sia necessario per trasmettere la forza del loro sentire, quasi come se i tratti che li renderebbero riconoscibili dovessero restare celati perché in fondo ciò che conta è la loro interiorità. La gamma cromatica si trasforma sulla base del soggetto scelto ma anche dello stile a cui il suo impulso la spinge, dunque più luminosa e solare quando resta legata al Secessionismo Viennese, più cupa quando invece si inoltra nell’Espressionismo perché il mondo delle emozioni può essere scoperto e svelato solo andando dentro le profondità dell’animo, attingendo a tutto quel ventaglio di sensazioni che non necessariamente riescono a essere positive anzi, spesso sono proprio quelle più oscure ad aver bisogno di raggiungere la luce per essere superate.

Nella tela Monochromatic feeling tutto ciò che esce in maniera chiara e riconoscibile è l’occhio chiuso da cui scendono lacrime scure a causa della loro forza spinta da un dolore interiore, da una disillusione, da un’aspettativa irrealizzata che induce la protagonista a raccogliersi in un istante di sofferenza che deve esse affrontato, accolto e compreso. Sophia Iakovidi immortala la sua protagonista esattamente in quel frangente, rivelandone solo il necessario per far fuoriuscire con grande impatto quella sensazione che appartiene in fondo a ciascun essere umano e che dunque può essere ricevuta in maniera spontanea e immediata dall’osservatore.

In Polychromatic mind invece ritrae un nudo femminile da dietro, escludendo pertanto tutta la valenza sessuale che era tipica di Egon Schiele, ma lasciando emergere la forza e l’introspezione di quel momento in cui la donna è sola con se stessa, come se mettendosi a nudo compisse un cammino di consapevolezza sulle sue debolezze e sulla sua forza, e dunque le tonalità utilizzate dalla Iakovidi tendono al positivo, all’armonia tra forma esteriore e forma interiore che inducono la donna a sentirsi seducente e sensuale proprio in virtù di quella sicurezza in se stessa. Le braccia aperte che sembrano invitare ad avvicinarsi un partner solo immaginato poiché escluso dalla tela, sono in realtà una metafora di tutto ciò che l’individuo, quando raggiunge il proprio equilibrio e la coscienza di quanto tutto dipenda da se stesso, sia in grado di ricevere se si pone in atteggiamento di apertura nei confronti di quanto la vita può offrire.

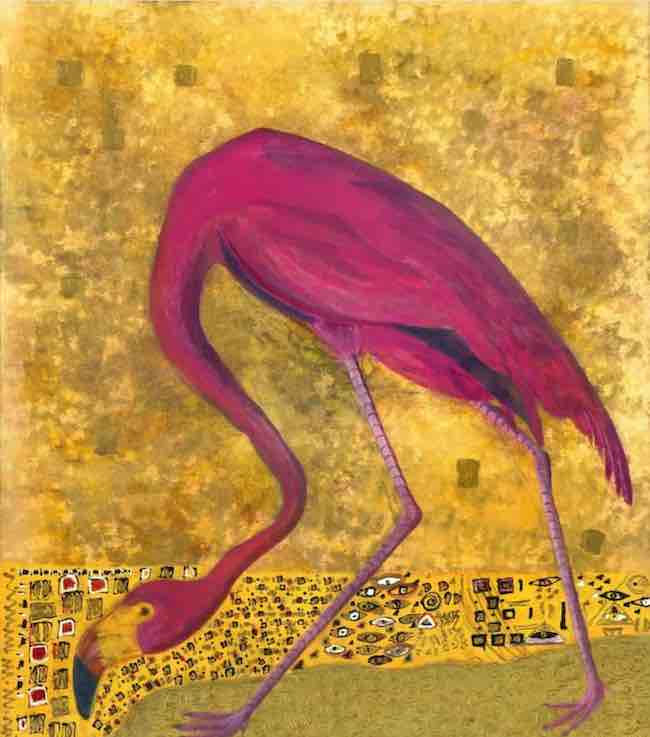

Nelle opere più legate al Secessionismo Viennese, come in Pink-Audubins flamingo, l’approccio di Sophie Iakovidi diviene più estetico, più orientato alla purezza della bellezza, sebbene lo stile pittorico rimanga sempre espressionista, e dunque la forza emozionale viene equilibrata da una ricercatezza, da un’eleganza arricchita dalla foglia oro e da quella sfarzosità che contraddistingue le opere di Gustav Klimt e che viene riproposta in questa tela in cui tutto ciò che deve emergere è la poesia del fenicottero rosa accompagnato da uno sfondo sognante, come se il grande trampoliere emergesse da un luogo fiabesco. In basso l’artista inserisce simboli tradizionali della cultura greca, unendo pertanto nella magia dell’arte le sue due origini, come l’occhio che nelle credenze popolari è una protezione contro l’invidia e i malauguri.

Ma Sophie Iakovidi non può dimenticare anche il paese che le appartiene per eredità genetica familiare ma in cui non vive, avendo scelto di restare in Grecia, e che si concretizza nel dipinto Austrian dream in cui il tratto espressionista si declina nel paesaggio, uno scorcio invernale e innevato, contraddistinto da un cielo scuro perché denso di nubi, che però non riesce a oscurare il candore della neve e la spontaneità degli animali che abitano quei luoghi lontani eppure vicini al suo cuore. L’intensità della nevicata, sottolineata da puntini che ricordano la tecnica del Pointillisme, sembra avvolgere l’osservatore che si sente coinvolto dalla pace e dalla tranquillità del paesaggio.

Sophie Iakovidi espone regolarmente le sue opere in diverse gallerie di Atene e sta per iniziare un percorso anche all’estero per farsi conoscere e apprezzare anche da un pubblico internazionale.

SOPHIE IAKOVIDI-CONTATTI

Email: sophie.iakovidi@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sophie.iakovidi

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/soph_ikv/

Sophie Iakovidi’s pictorial explorations, hovering between Viennese Secessionism and Expressionism to delicately portray intimate emotions

The need to draw on the most recent past in order to design a personal style through which to express profound sensations while adapting them to a modern life that is completely different from the roots that inspired them, is a distinctive characteristic of many artists who live and work in the present day, taking advantage of the privilege of having been able to study those revolutionary masters of the 20th century, thus having the opportunity to rework their expressive intuitions by mixing and blending them in the full freedom that characterises 21st century art. Today’s artist presents exactly this peculiarity, increased and enhanced by her mixed family roots that have always made her perceive the positivity and value of the union between different cultures, leading her to apply this value to her artworks as well.

The historical period between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century was marked by a series of pictorial and sculptural revolutions that were destined to break the previous patterns, linked to Realism and the need to adhere to academic rules, and to strongly affirm both the need to foreground the artist’s interiority and that for freedom to experiment and subvert those dogmas which until less time before were unimaginable to break without being excluded from the cultural salons that counted. Among the various movements of that era, one emerged that affected European nations, differed in artistic history but all adhering with enthusiasm and a strong creative drive to the proposals of the creators of a new way of conceiving an artwork, including artisanal techniques and extending creativity to fields that until recently had been completely unexplored. Art Nouveau, which in Italy took the name of Stile Liberty, in Spain was called Modernism, in England Arts and Crafts and in Austria Vienna Secession, was perhaps the first to establish the importance of the applied arts, of craftsmanship as the result of man’s work that was to contrast the depersonalising industrialisation of the period, extending creative possibilities to glass, metals and carpets, and introducing decorative techniques to painting that still retained a refined aesthetic taste with a strong impact and sumptuous charm.

The canvases of Gustav Klimt, the greatest exponent of Vienna Secession, traced a path that was, however, limited to his genius and came into contrast with another innovative painting current, Expressionism, which, on the contrary, imposed itself to completely renounce aesthetics in order to privilege emotion, intense sensations, even if this meant renouncing beauty, the relevance to an observed reality that was often not akin to the interiority that needed to escape. It was precisely from the ashes of the Secessionist revolution that Vienna saw the birth of one of the greatest masters of Expressionism, Egon Schiele, who made the ugliness and deformity of the bodies depicted his creative line, because what had to emerge was existential unease, the fears of the soul that could be soothed and reassured with sexuality. The Greek artist Sophie Iakovidi approaches spontaneously the two great masters of the early 20th century by virtue of her mixed Greek-Austrian origins, which pushed her towards experimentation, towards communication between languages that were apparently separate yet somehow reconcilable precisely because of that freedom of expression that characterises the contemporary era and that allows her to search for her own stylistic signature that is at once original but also linked to those historical roots that infuse inspiration and knowledge. On the one hand, her canvases tend towards Vienna Secession inspired by Klimt, with an extensive use of gold leaf and gold tones that envelop her characters, often delicately reclining to express sweetness and emotional intensity; on the other hand, she approaches Expressionism, in some paintings close to that of Schiele, of which she keeps the intensity and tendency to internalise an emotion, a sensation or a point of view on the observed that is filtered and reinterpreted by her sensitivity and that reaches the observer directly and immediately. What emerges clearly is the delicacy with which Sophie Iakovidi deals with emotions, almost with a discretion that induces her to respect her protagonists, without revealing more than is necessary to convey the strength of their feeling, almost as if the traits that would make them recognisable should remain concealed because in the end what counts is their interiority.

The chromatic range is transformed on the basis of the subject chosen but also of the style to which her impulse drives her, thus brighter and sunnier when she remains linked to Viennese Secessionism, darker when she moves into Expressionism because the world of emotions can only be discovered and unveiled by going into the depths of the soul, drawing on the whole range of sensations that are not necessarily positive, on the contrary, it is often the shady ones that need to reach the light to be overcome. In the canvas Monochromatic feeling, all that comes out clearly and recognisably is the closed eye from which dark tears flow because of their force driven by an inner pain, a disillusionment, an unrealised expectation that induces the protagonist to gather herself in a moment of suffering that must be faced, welcomed and understood. Sophia Iakovidi immortalises her protagonist exactly at that juncture, revealing only what is necessary to bring out with great impact that feeling which belongs deep down to every human being and which can therefore be received spontaneously and immediately by the observer. In Polychromatic mind, on the other hand, she portrays a female nude from behind, thus excluding all the sexual significance that was typical of Egon Schiele, but allowing the strength and introspection of that moment in which the woman is alone with herself to emerge, as if by laying herself bare she were making a journey of awareness of her weaknesses and her strength, and thus the tones used by Iakovidi tend towards the positive, towards harmony between exterior form and interior form that induce the woman to feel seductive and sensual precisely by virtue of that self-confidence. The open arms that seem to invite a partner only imagined as excluded from the canvas to approach, are in reality a metaphor for all that the individual, when he reaches his own equilibrium and the awareness of how much everything depends on himself, is capable of receiving if he adopts an attitude of openness towards all that life can offer.

In the paintings more closely linked to Vienna Secession, as in Pink-Audubins flamingo, Sophie Iakovidi’s approach becomes more aesthetic, more oriented towards the purity of beauty, although the pictorial style always remains expressionist, and thus the emotional force is balanced by a refinement by an elegance enriched by gold leaf and by that opulence that distinguishes the works of Gustav Klimt and which is re-proposed in this canvas in which all that needs to emerge is the poetry of the pink flamingo accompanied by a dreamy background, as if the great wader were emerging from a fairy-tale place. At the bottom, the artist inserts traditional symbols of Greek culture, thus uniting her two origins in the magic of art, such as the eye, which in popular belief is a protection against envy and bad luck. But Sophie Iakovidi also cannot forget the country that belongs to her by genetic family inheritance but in which she does not live, having chosen to remain in Greece, and which is embodied in the painting Austrian dream in which the expressionist trait is declined in the landscape, a winter and snowy view, marked by a dark sky because it is dense with clouds, which however cannot obscure the whiteness of the snow and the spontaneity of the animals that inhabit those faraway places yet close to her heart. The intensity of the snowfall, emphasised by dots reminiscent of the Pointillisme technique, seems to envelop the observer, who feels caught up in the peace and tranquillity of the landscape. Sophie Iakovidi regularly exhibits her artworks in various galleries in Athens and is about to start a journey abroad in order to make herself known and appreciated by an international audience as well.