Le fragilità, le debolezze, la tendenza a perdersi all’interno di percorsi e di quesiti che non sono mai stati davvero spiegati, appartengono all’uomo contemporaneo tanto quanto sono appartenute a quello del passato perché forse in fondo è impossibile dare una spiegazione definitiva a ciò che è in costante cambiamento ed evoluzione; tuttavia l’arte si è sempre posta come mezzo interpretativo quanto meno di una realtà relativa, poiché la verità assoluta è sempre risultata sfuggente e inconoscibile, quella cioè legata al punto di vista e al personale sentire dell’esecutore di un’opera, anche quando l’autore stesso proclamava l’intenzione di distaccarsi dal mondo emotivo. Il protagonista di oggi sceglie la sfera, simbolo di perfezione e di compiutezza di ogni tempo, per far fuoriuscire le sue riflessioni sull’eterna spaccatura tra ideale, verso cui l’essere umano tende, e il reale, l’effettiva capacità di dare compimento a quella ricerca.

I primi anni del Novecento segnarono una svolta importante nel modo di approcciare e concepire l’arte poiché tutto ciò che era legato alle precedenti regole, agli schemi accademici fino a quel momento considerati la base imprescindibile dell’espressione creativa vennero sovvertiti, stravolti e completamente rinnegati in nome di un’innovazione necessaria a dare un nuovo senso a un concetto ormai superato, a introdurre la necessità di andare alla sostanza anziché fermarsi alla forma, a spingersi oltre il visibile per scoprire da un lato la supremazia dell’arte intesa come gesto plastico assolutamente autonomo dalla riproduzione di ciò che lo sguardo osserva, dall’altro l’introduzione del significante che emerge esattamente grazie all’assenza di un’immagine attinente alla realtà. Colui che fu considerato il fondatore dell’Astrattismo, Vassily Kandinsky, sottolineò la sussistenza delle sensazioni malgrado l’occhio non fosse in grado di razionalizzare la somma di forme indefinite che contraddistinguevano la sua produzione artistica; il legame dunque tra mondo interiore e pittura astratta era essenziale per l’intento espressivo del grande maestro del Novecento, così come lo era la connessione con la musica grazie alla quale le emozioni potevano liberarsi con maggiore facilità durante l’atto pittorico. Le forme privilegiate erano le linee sinuose alternate ad altre geometriche più rigorose come il triangolo e il rettangolo, e poi la sfera che nel corso del tempo assunse nella sua produzione via via maggiore rilevanza. Qualche anno dopo emersero però correnti pittoriche, anch’esse fermamente orientate a mantenere l’Astrattismo come principio imprescindibile per l’indipendenza dell’arte da ogni contingenza, le quali però irrigidirono l’espressione pittorica fino al punto di delegare alla razionalità, rinunciando pertanto al lirismo teorizzato da Kandinsky, e al rigore geometrico e cromatico l’intera loro espressione pittorica. Il Suprematismo di Kazimir Malevich asciugò l’opera d’arte dai colori tenui e sfumati andando verso una gamma più ristretta seppur ancora ampia rispetto a quella dei soli colori primari, mentre le forme geometriche accettate erano rigorosamente quadrangolari, rette od oblique; parallelamente alla sua opera emerse con il Neoplasticismo un’ulteriore estremizzazione, visibile nelle opere di Piet Mondrian e Theo Van Doesburg, dove i colori primari erano gli unici ammessi sulla tela e persino la linea obliqua, considerata ambigua come la forma circolare o sferica, doveva essere rigorosamente esclusa. Con l’Astrattismo Geometrico fu superata la rigidità del Neoplasticismo ma non ancora recuperata quella connessione con le sensazioni e la morbidezza esecutiva teorizzata e contraddistinguente invece l’opera di Kandinsky.

L’artista lombardo Paolo Cantù Gentili si riavvicina al maestro dell’Astrattismo Lirico reintroducendo e rendendo protagonista assoluta proprio la sfera, quella figura che rappresenta da sempre la perfezione, la compiutezza superiore, e il simbolo dell’evoluzione dell’individuo e della sua esistenza; dalla filosofia greca dell’antichità fino a quelle orientali, la sfera è un simbolo fondamentale che costituisce la base stessa della vita, quel tendere verso un costante ricongiungimento con l’energia superiore, o universale, che rappresenta il compimento dell’individuo.

Parmenide ne aveva fatto il simbolo della perfezione assoluta, l’entità superiore, l’assoluta armonia rappresentante l’Essere supremo, tanto quanto nella filosofia orientale il Tao simboleggia nella sua circolarità la tensione costante verso la ricerca di un miglioramento del sé, quel ciclo di esperienza che conduce l’individuo verso una maggiore conoscenza e coscienza del proprio cammino, della propria spiritualità.

In Paolo Cantù Gentili invece la sfera è strumento di approfondimento, di studio, di interrogazione sui grandi temi dell’esistenza che sono da sempre oggetto di riflessione da parte di studiosi ma anche dell’uomo comune che cerca di applicare all’ambito pratico le grandi domande spesso rimaste senza risposta, e l’interazione, la correlazione emozionale che domina la sua esistenza; la gamma cromatica scelta è decisamente vivace, vibrante tanto quanto lo sono gli elementi che compongono le sue tele, elementi in apparente perpetuo movimento quasi come se rappresentassero il cammino da compiere per realizzare il concetto espresso attraverso il titolo.

Nella tela Demiurge (Demiurgo) Paolo Cantù Gentili riprende la figura platonica del divino artigiano in grado di superare l’eterno dualismo tra mondo delle idee e realtà sensibile, laddove ancora una volta la sfera rappresenta quell’ideale che funge da esempio, da modello da perseguire per l’essere umano, quel concatenamento di concetti perfetti verso cui l’uomo deve tornare dopo aver sperimentato la corruttibilità del mondo reale. Per l’artista il migliore dei mondi possibili che il Demiurgo genera si ricongiunge alla forma sferica, dunque naturalmente perfetta e inattaccabile, ma anche a tonalità morbide, solari, positive per quella prospettiva di crescita e di miglioramento dell’essenza che intorno a esse si libera.

E ancora nell’opera Fenditure nella divinità Paolo Cantù Gentili si spinge verso il fascino assolutamente umano di cercare quel contatto identificativo con la spiritualità, con il divino a cui l’individuo si affida per oltrepassare gli ostacoli del vivere, a cui demanda tutto ciò che non può spiegare, conoscere, consegnandogli a volte il proprio destino. Eppure, sembra suggerire l’artista, l’essere umano è comunque al centro della sua stessa esistenza, perché il solo fatto di rivolgersi all’entità superiore ne consacra in qualche modo il ruolo attribuitogli e dunque l’uno sembra essere imprescindibile per l’altro; le tre sfere sono inserite all’interno di uno schema più geometricamente regolare, una sorta di autodeterminazione che pone più in basso le passioni primordiali contraddistinte dal colore rosso, al centro un passaggio intermedio che corrisponde al percorso di elevazione attraverso la consapevolezza della determinatezza del ruolo dell’uomo e infine in alto l’essenza divina, quel punto di arrivo desiderato ma in fondo mai raggiunto che domina l’intera vita.

In Palpiti invece l’artista scende verso le emozioni più spirituali ma connesse all’individuo e perciò più terrene rispetto al più alto ideale espresso nelle tele precedenti, e avvicina le circolarità protagoniste di un universo intimo, quello delle sensazioni che hanno bisogno di un’atmosfera più soffusa e sfumata per ascendere verso la coscienza; lo sfondo su cui emergono le emozioni, quel groviglio di sensazioni che vengono osservate solo calandosi nel silenzio, nell’intimità delle proprie profondità, sono definite da uno sfondo polveroso, grigio come la suggestione necessaria per compiere il percorso introspettivo. Quello a seguito del quale i palpiti, le sensazioni riescono a fuoriuscire in maniera più nitida.

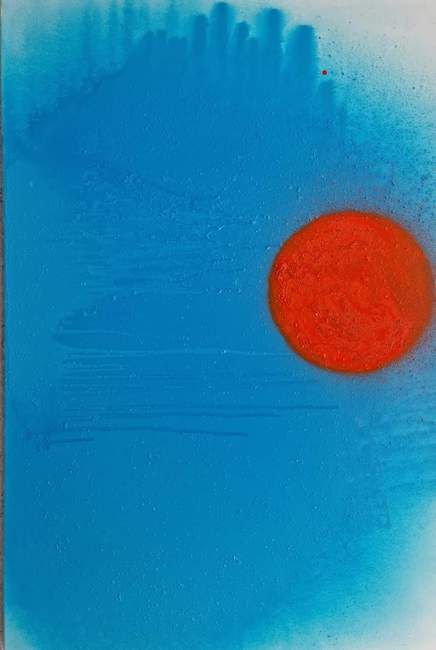

Dirompente, vivace e travolgente appare al contrario la tela Closeness (Vicinanza), l’opera in copertina articolo, in cui l’interrelazione diviene risorsa, capacità di superare insieme ostacoli e difficoltà ed è proprio grazie a quell’apertura empatica che ogni cosa assume maggiore piacevolezza, maggiore intensità e, di conseguenza, più predisposizione a osservare il risvolto positivo degli accadimenti.

Paolo Cantù Gentili è il fondatore del gruppo artistico Disnormalità, ha all’attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive in Italia e una videoesposizione a New York; le sue opere sono state inserite in molti importanti cataloghi d’arte.

PAOLO CANTÙ GENTILI-CONTATTI

Email: paocantu44@gmail.com

Sito web: https://arcaniblog.wordpress.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paolo.cantu4

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/paolocantugentili/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/paolo-cant%C3%B9-b0946043/

Paolo Cantù Gentili’s Abstractionism, the perfection of the spherical shape to tell the incompleteness of the man of all times

Fragilities, weaknesses and the tendency to lose oneself in paths and questions that have never been truly explained belong to contemporary man just as much as they did to that of the past, because perhaps it is impossible to give a definitive explanation for what is constantly changing and evolving; however, art has always set itself up as a means of interpreting at least a relative reality, since the absolute truth has always been elusive and unknowable, i.e. linked to the point of view and personal feelings of the artist, even when the author himself proclaimed his intention to detach from the emotional world. Today’s protagonist chooses the sphere, the symbol of perfection and fulfilment of all time, to bring out his reflections on the eternal rift between the ideal, towards which the human being tends, and the real, the actual ability to give fulfilment to that quest.

The early years of the twentieth century marked an important turning point in the way of approaching and conceiving art, since everything that was linked to the previous rules, to the academic schemes that until then had been considered the essential basis of creative expression were subverted, overturned and completely repudiated in the name of an innovation necessary to give a new meaning to an outdated concept, to introduce the need to go to the substance instead of stopping at the form, to go beyond the visible to discover on the one hand the supremacy of art understood as a plastic gesture absolutely independent from the reproduction of what the eye observes, and on the other hand the introduction of the signifier that emerges precisely thanks to the absence of an image related to reality. Vassily Kandinsky, who was considered the founder of Abstractionism, emphasised the existence of sensations despite the fact that the eye was unable to rationalise the sum of indefinite forms that distinguished his artistic production; the link between the inner world and abstract painting was therefore essential to the expressive intent of the great 20th-century master, as was the connection with music, thanks to which emotions could be more easily released during the act of painting. The preferred forms were sinuous lines alternating with more rigorous geometric ones such as the triangle and the rectangle, and then the sphere, which over time became more and more important in his production.

A few years later, however, pictorial currents emerged, which were also firmly oriented towards maintaining Abstractionism as an essential principle for the independence of art from all contingencies, but which stiffened pictorial expression to the point of delegating the entirety of their pictorial expression to rationality, thus renouncing the lyricism theorised by Kandinsky, and to geometric and chromatic rigour. Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism wiped away the artwork of soft, muted colours by moving towards a narrower, though still wide range of primary colours alone, while the geometric shapes accepted were strictly quadrangular, straight or oblique; parallel to his work, a further extreme emerged with Neoplasticism, visible in the works of Piet Mondrian and Theo Van Doesburg, where primary colours were the only ones allowed on the canvas and even the oblique line, considered ambiguous like the circular or spherical shape, had to be strictly excluded. With Geometric Abstractionism the rigidity of Neoplasticism was overcome, but not yet reclaimed that connection with sensations and softness of execution theorised and distinguishing Kandinsky’s work. The Lombard artist Paolo Cantù Gentili gets close to the master of Lyrical Abstraction by reintroducing and making the sphere the absolute protagonist, the figure that has always represented perfection, superior completeness, and the symbol of the evolution of the individual and his existence; from ancient Greek philosophy to oriental philosophy, the sphere is a fundamental symbol that constitutes the very basis of life, that tendency towards a constant reunion with the superior or universal energy that represents the fulfilment of the individual. Parmenides had made it the symbol of absolute perfection, the superior entity, the absolute harmony representing the supreme Being, just as in oriental philosophy the Tao symbolises in its circularity the constant tension towards the search for an improvement of the self, that cycle of experience that leads the individual towards greater knowledge and awareness of his own path, of his own spirituality. In Paolo Cantù Gentili’s artwork, on the other hand, the sphere is an instrument for in-depth study, for questioning the great themes of existence, which have always been the subject of reflection by scholars but also by the ordinary man who seeks to apply to the practical field the great questions that often remain unanswered, and the interaction, the emotional correlation that dominates his existence; the range of colours chosen is decidedly lively, as vibrant as the elements that make up his canvases, elements in apparent perpetual movement almost as if they represented the path to be followed to realise the concept expressed in the title.

In the canvas Demiurge Paolo Cantù Gentili takes up the Platonic figure of the divine craftsman capable of overcoming the eternal dualism between the world of ideas and sensible reality, where once again the sphere represents that ideal which serves as an example, a model for human beings to pursue, that chain of perfect concepts towards which man must return after experiencing the corruptibility of the real world. For the artist, the best of the possible worlds that the Demiurge generates is reunited with spherical form, which is therefore naturally perfect and unassailable, but also with soft, sunny, positive tones for that prospect of growth and improvement of the essence that is released around them. And again, in the artwork Fenditure nella divinità (Splits in the Divinity), Paolo Cantù Gentili pushes towards the absolutely human fascination of seeking that identifying contact with spirituality, with the divine to which the individual relies to overcome the obstacles of life, to which he entrusts everything he cannot explain, know, sometimes handing over his own destiny. And yet, the artist seems to suggest, the human being is in any case at the centre of his own existence, because the mere fact of addressing the superior entity in some way consecrates the role attributed to him, and so one seems to be inseparable from the other; The three spheres are inserted into a more geometrically regular pattern, a sort of self-determination that places the primordial passions, marked by the colour red, at the bottom; in the centre, an intermediate passage that corresponds to the path of elevation through the awareness of the determinacy of man’s role; and finally, at the top, the divine essence, that desired point of arrival but, in the end, never reached, which dominates the whole of life.

In Palpiti (Heartbeats), on the other hand, the artist descends towards emotions that are more spiritual but connected to the individual and therefore more earthly than the higher ideal expressed in the previous canvases, and brings closer the circularities that are the protagonists of an intimate universe, that of sensations that need a more suffused and nuanced atmosphere to ascend towards consciousness; the background against which the emotions emerge, that tangle of sensations that can only be observed by descending into silence, into the intimacy of one’s own depths, are defined by a dusty background, grey like the suggestion needed to make the introspective journey. This is the path after which the throbbing, the sensations are able to emerge more clearly. On the contrary, the canvas Closeness, the artwork on the cover of the article, appears disruptive, lively and overwhelming, in which interrelation becomes a resource, the ability to overcome obstacles and difficulties together, and it is thanks to this empathic openness that everything becomes more pleasant, more intense and, consequently, more willing to observe the positive side of events. Paolo Cantù Gentili is the founder of the artistic group Disnormalità, and has taken part in many group exhibitions in Italy and a video exhibition in New York; his artworks have been included in many important art catalogues.