La capacità di andare oltre la forma osservata, quella concreta a cui lo sguardo è abituato, ha contraddistinto gran parte degli artisti del secolo scorso, soprattutto quelli per cui il significato oppure l’approccio plastico dovevano essere predominanti su qualsiasi tipo di attinenza al vissuto quotidiano; nell’arte contemporanea le linee base sono state ampliate, mescolate e oltrepassate grazie alla possibilità di approfondire lo studio e la conoscenza di quei maestri innovatori in grado di aprire la strada a nuove idee suggerendo agli artisti di oggi di mantenersi saldi e fedeli alla loro indole espressiva, liberandosi dalle regole e creandone di proprie. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi ha compiuto un percorso evolutivo ed esplorativo non solo della propria inclinazione creativa ma anche nei confronti di un linguaggio stilistico che ha saputo far evolvere sulla base della propria visione.

Il Novecento è stato indubbiamente un secolo rivoluzionario, complesso anche a causa delle resistenze del mondo accademico nei confronti di quei ribelli che si erano imposti di dare una svolta, di generare una spaccatura tra l’approccio espressivo più tradizionale e quelle nuove idee più al passo con i tempi che avevano bisogno di fuoriuscire con forza per imporsi in un contesto conservatore e resistente. Lo spirito più sovversivo fu mostrato da quel gruppo di creativi che desideravano allontanarsi completamente dall’immagine conosciuta, quella quotidianamente davanti allo sguardo, perché riprodurre fedelmente la realtà era limitante per l’arte, ormai facilmente accessibile da altri metodi di riproduzione come la fotografia e l’emergente cinematografo, e lo era anche per la ricerca dell’artista che staccandosene poteva concentrarsi sulla purezza delle forme e sui concetti più celati. A partire dal Suprematismo e dal De Stijl con il loro approccio distaccato e puramente plastico per finire al Dadaismo, dove addirittura ogni regola stilistica venne annullata, dissacrata e rivoluzionata al punto di trasformare oggetti di uso comune in provocazioni artistiche, tutti i movimenti astrattisti che si avvicendarono nel Ventesimo secolo sottolinearono la necessità di epurare l’opera d’arte dall’emotività dell’artista, legando il suo punto di vista solo alla ricerca o al pensiero razionale. Tuttavia ben presto si concretizzò l’esigenza di tornare verso la soggettività interiore, pur mantenendo la non forma come base pittorica e scultorea. All’interno di questo processo si distinsero due artisti che in maniera diversa sembrarono giungere a una simile sintesi espressiva, Henri Matisse, che da un inizio Fauves si spostò verso un Espressionismo via via più stilizzato fino a stabilizzarsi negli ultimi anni all’interno di un contesto Informale però intriso delle emozioni suscitate in lui dalla natura; e poi Jean Arp, artista eclettico e sperimentatore, tra i fondatori del Dadaismo da cui poi lentamente si distaccò proprio per mantenersi fedele alla sua natura istintiva che lo conduceva verso l’assoluta libertà creativa, avvicinandosi in una seconda fase al Surrealismo, in cui mostrava un approccio più analogo a quello di Joan Mirò, e infine riavvicinandosi alla natura e all’emozione a essa legata, non poté fare a meno di sposare l’istintualità emozionale con l’opera che rientrava nell’intento artistico dell’Espressionismo Astratto. Le sue linee sinuose e tondeggianti, costituite da forme indefinite dentro cui si può immaginare tutto, sono state fonte di ispirazione per l’artista greca Kiriaki Nikoladi, diplomata presso la Scuola di Belle Arti di Salonicco e per molti anni insegnante d’arte presso la scuola primaria; la sua natura espressiva non riusciva però a essere soddisfatta nell’insegnamento perché la tendenza sperimentatrice, quella che la accomuna proprio a Jean Arp, l’ha spinta a inseguire la carriera artistica inducendola a compiere un cammino di approfondimento, di scoperta e di evoluzione del suo linguaggio artistico.

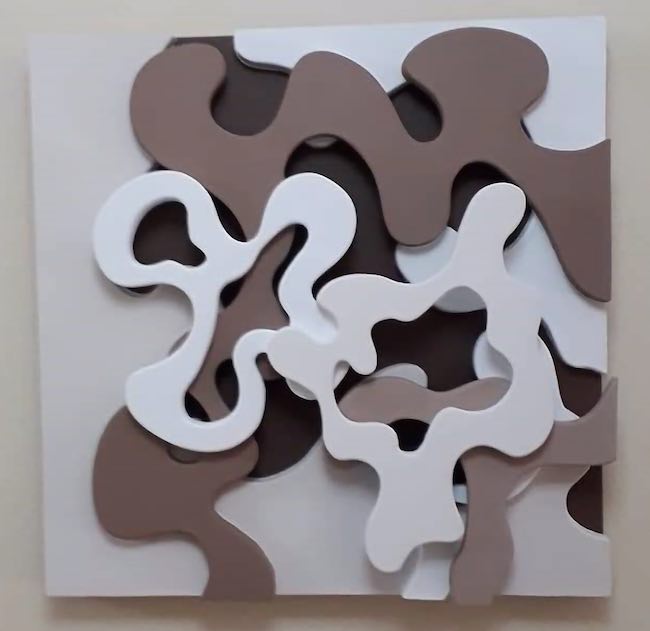

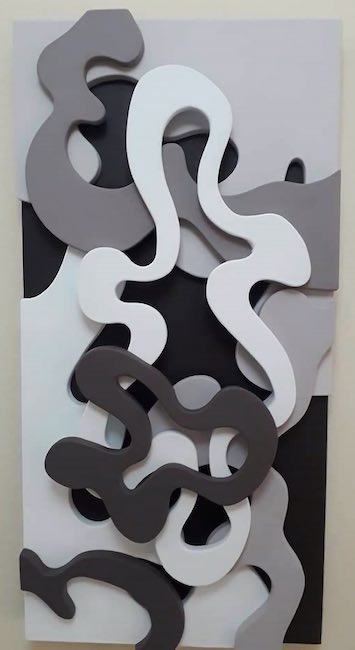

Nello stile attuale mescola le forme stilizzate e tondeggianti, che sembrano essere un’evoluzione e una sintesi di quelle di Arp e di Matisse, a una struttura materica, rigida, quasi a dare consistenza a quelle ondulazioni che si sovrappongono e si sovrastano entrando in contatto con lo spazio circostante, comunicando direttamente con l’osservatore, chiamandolo verso le sinuosità che corrispondono alle curve della vita, alle differenze dei pensieri che si susseguono osservando un paesaggio, riflettendo su un concetto o semplicemente lasciandosi conquistare dall’accostamento di tonalità in perfetta armonia tra loro, come se l’equilibrio cromatico potesse contribuire a infondere un senso di pace e di ordine.

Le sue sono pittosculture dove il Fibran, un materiale originariamente nato per l’edilizia, si associa al colore acrilico che Kikiaki Nikoladi sceglie di utilizzare in scala, dunque i beige saranno associati ai marroni, i bianchi ai grigi e gli acqua agli azzurri intensi perché, sembra suggerire l’artista, tutto ciò che in fondo l’essere umano cerca è l’equilibrio, un’armonia troppo spesso inseguita senza che sia raggiunta, un bilanciamento tra gli estremi dell’esistenza. Per esprimere questo concetto è necessario lasciare che le sensazioni fuoriescano, ecco il motivo della solidità delle forme, in maniera netta e decisa, lasciandosi osservare, capire, permettendo all’interiorità di comprenderne la consistenza e l’ingombro che generano nelle profondità in cui si nascondono.

Dunque per la Nikoladi le emozioni sono importanti, intense quanto lo sono le percezioni profonde che devono trovare una valvola di sfogo, una fuoriuscita prima che si cristallizzino al punto di non essere più comprensibili; così come è importante la contemplazione, la riflessione che la fa tendere verso forme astratte ma ben definite, geometriche perché l’interiorizzazione ha bisogno di distaccarsi da tutto ciò che lo sguardo conosce ma prevalentemente tondeggianti poiché davanti alla durezza della realtà è necessario che l’interiorità sia più morbida, che sia in grado di accogliere quelle complicanze che impediscono al sentire di incanalarsi in strade diritte e definite aprendosi invece a sfumature costituenti la base stessa della conoscenza di sé, di ciò che circonda l’essere umano, e degli altri con cui si interagisce.

Nell’opera Sea of Greece Kiriaki Nikoladi non può fare a meno di narrare i colori del meraviglioso paese in cui è nata, quelle sfumature di azzurro che non solo contraddistinguono il mar Egeo ma si uniscono al cielo generando un’armonia in grado di conquistare l’anima che davanti alla contemplazione di tanta armonica bellezza non può che lasciarsi andare, ascoltare il ritmo lento delle onde in sintonia con il vibrare delle sue corde emotive. La gradazione cromatica e le figure curvilinee si avvolgono richiamando il movimento del mare, cullando lo sguardo in maniera quasi ipnotica e inducendolo a entrare in sintonia con quella natura con cui da sempre il popolo greco è abituato a misurarsi e a ringraziare per la sua presenza e i suoi doni.

Le linee hanno costituito il punto base della ricerca artistica di Kiriaki Nikoladi perché anche nella produzione precedente, quella ancora pittorica, la realtà era scomposta e rappresentata attraverso di esse sia nel determinare le sfumature cromatiche sia per lasciar intuire quel movimento universale molto vicino al Pantha rei eracliteo che contraddistingue inevitabilmente tutta la realtà, persino quella che si crede essere immobile; la tela The loneliness ode appartiene a quelle opere che sono state il punto di partenza per l’evoluzione stilistica, in cui appare evidente la scomposizione in onde energetiche che si sono successivamente ingrandite fino a rinunciare all’immagine conosciuta per permanere sotto forma di energia che parte dal soggetto per interpretare l’oggetto o il concetto.

Tanto forte è l’esigenza di libertà che traspare dall’approccio esplorativo di Kiriaki Nikoladi, da lasciare molte opere senza titolo permettendo così all’osservatore di porsi in maniera completamente aperta e interattiva nei confronti delle sue pittosculture, senza alcuna indicazione da parte dell’artista perché è solo lasciando un canale aperto che è possibile generare quel contatto unico, quella connessione tra l’espressività spontanea dell’autore e le corde interiori di chi riceve e che decodifica sulla base della propria esperienza, sensibilità e approccio alla vita. Kiriaki Nikoladi ha preso parte alla mostra Pandora’ s box presso il Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art nel 2013, al Bazaart presso la galleria Ilios di Salonicco nel 2015 e al French Institute of Salonicco nel 2019. A gennaio 2023 ha partecipato alla collettiva La grande bellezza presso la Medina Art Gallery di Roma.

KIRIAKI NIKOLADI-CONTATTI

Email: twin.camgti@windowslive.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kiriaki.nikolaidi

Kiriaki Nikoladi’s three-dimensional curvilinear forms, where matter meets Abstract Expressionism

The ability to go beyond the observed form, the concrete one to which the eye is accustomed, characterised most of the artists of the last century, especially those for whom meaning or the plastic approach had to be predominant over any kind of relevance to everyday life; in contemporary art, the basic lines have been broadened, mixed and crossed thanks to the possibility of deepening the study and knowledge of those innovative masters who were able to pave the way for new ideas, suggesting to today’s artists that they remain steadfast and faithful to their expressive nature, freeing themselves from rules and creating their own. The artist I am going to tell you about today made an evolutionary and explorative journey not only of her own creative inclination, but also of a stylistic language that she was able to evolve on the basis of her own vision.

The 20th century was undoubtedly a revolutionary century, complex also because of the resistance of the academic world towards those rebels who had set out to make a breakthrough, to generate a split between the more traditional expressive approach and those new ideas more in step with the times that needed to break out forcefully to impose themselves in a conservative and resistant context. The most subversive spirit was shown by that group of creatives who wished to move away completely from the known image, the one daily before the eyes, because faithfully reproducing reality was limiting for art, now easily accessible by other methods of reproduction such as photography and the emerging cinematograph, and it was also limiting for the artist’s research, which by breaking away from it could concentrate on the purity of forms and the most concealed concepts. Beginning with Suprematism and De Stijl with their detached and purely plastic approach and ending with Dadaism, where even every stylistic rule was annulled, desecrated and revolutionised to the point of transforming everyday objects into artistic provocations, all the abstractionist movements that followed in the 20th century emphasised the need to purge the work of art of the artist’s emotionality, binding its point of view solely to research or rational thought. However, soon materialised the need to return to inner subjectivity, while maintaining non-form as the basis for painting and sculpture. Within this process, stood out two artists who, in different ways, seemed to reach a similar expressive synthesis, Henri Matisse, who moved from a Fauves beginning towards an increasingly stylised Expressionism until stabilising in his later years within an Informal context, but imbued with the emotions aroused in him by nature; and then Jean Arp, an eclectic artist and experimenter, one of the founders of Dadaism from which he then slowly detached himself in order to remain faithful to his instinctive nature that led him towards absolute creative freedom, approaching Surrealism in a second phase, in which he displayed an approach more akin to that of Joan Mirò, and finally drawing closer to nature and the emotion attached to it, he could not help but marry emotional instinctuality with the artwork that was part of the artistic intent of Abstract Expressionism.

Its sinuous, rounded lines, consisting of undefined shapes within which one can imagine anything, were a source of inspiration for the Greek artist Kiriaki Nikoladi, a graduate of the School of Fine Arts in Thessaloniki and for many years a primary school art teacher; however, her expressive nature could not be fulfilled in teaching because her experimental tendency, which she shares with Jean Arp, drove her to pursue a career in art, leading her on a path of deepening, discovery and evolution of her artistic language. In her current style, she mixes stylised and rounded forms, which seem to be an evolution and synthesis of those of Arp and Matisse, with a material, rigid structure, almost as if to give consistency to those undulations that overlap, coming into contact with the surrounding space, communicating directly with the observer, calling him towards the sinuosities that correspond to the curves of life, to the differences in the thoughts that follow one another while observing a landscape, reflecting on a concept or simply allowing oneself to be won over by the juxtaposition of tones in perfect harmony with each other, as if the chromatic balance could contribute to instilling a sense of peace and order. Hers are pictosculptures where Fibran, a material originally created for the building trade, is associated with the acrylic colour that Kiriaki Nikoladi chooses to use in scale, so beiges will be associated with browns, whites with greys and aqua with intense blues because, the artist seems to suggest, all that the human being is basically looking for is balance, a harmony too often pursued without being achieved, an equilibrium between the extremes of existence. In order to express this concept, it is necessary to let the sensations escape, hence the reason for the solidity of the forms, in a clear and decisive manner, allowing themselves to be observed, to be understood, allowing the interiority to understand their consistency and the encumbrance they generate in the depths in which they hide.

So for Nikoladi, emotions are important, as intense as deep perceptions that must find an outlet, an escape before they crystallise to the point of no longer being comprehensible; in the same way, contemplation is important, the reflection that makes it tend towards abstract but well-defined forms, geometric because interiorisation needs to detach itself from everything that the eye knows, but prevalently rounded because in the face of the harshness of reality, it is necessary for interiority to be softer, to be able to accept those complications that prevent feeling from channelling itself along straight and defined paths, opening up instead to the nuances that form the very basis of knowledge of the self, of what surrounds the human being, and of the others with whom we interact. In the artwork Sea of Greece, Kiriaki Nikoladi cannot help but narrate the colours of the marvellous country where she was born, those shades of blue that not only distinguish the Aegean Sea but also join with the sky, generating a harmony capable of conquering the soul, which before the contemplation of such harmonious beauty cannot avoid to let itself go, listening to the slow rhythm of the waves in tune with the vibrating of its emotional chords. The gradation of colours and the curvilinear figures wrap themselves around recalling the movement of the sea, lulling the gaze in an almost hypnotic way and inducing it to enter into harmony with that nature with which the Greek people have always been accustomed to measure themselves and give thanks for its presence and gifts. Lines constituted the basic point of Kiriaki Nikoladi’s artistic research because even in her previous production, which is still pictorial, reality was broken down and represented through them both in determining the chromatic nuances and in allowing intuition of that universal movement very close to the Heraclitean Pantha rei that inevitably characterises all reality, even that which is believed to be immobile; the canvas The loneliness ode belongs to those artworks that have been the starting point for the stylistic evolution, in which the decomposition into energy waves that have subsequently enlarged to the point of renouncing the known image to remain in the form of energy that starts from the subject in order to interpret the object or concept is evident. So strong is the need for freedom that transpires from Kiriaki Nikoladi’s exploratory approach, that she leaves many works untitled, thus allowing the observer to be completely open and interactive with her pictosculptures, without any indication from the artist, because it is only by leaving a channel open that it is possible to generate that unique contact, that connection between the author’s spontaneous expressiveness and the inner chords of the recipient, which he decodes on the basis of his own experience, sensitivity and approach to life. Kiriaki Nikoladi took part in the exhibition Pandora’ s box at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art in 2013, in Bazaart at the Ilios Gallery of Thessaloniki in 2015 and at the French Institute of Thessaloniki in 2019. In January 2023, she participated in the group exhibition La grande bellezza at the Medina Art Gallery in Rome.