La necessità di superare la bidimensionalità ha costituito un passaggio importante nella storia dell’arte più recente generando una costante affermazione, spesso addirittura un distacco, da parte di alcuni artisti dai confini delineati dalla superficie limitante della tela; molti di loro hanno decisamente rinunciato alla staticità per fare arte in un modo innovativo, calato nello spazio circostante e poi, nell’estremizzazione della rilevanza dell’oggetto, distaccandosi completamente dalla base pittorica. L’artista di cui vi parlerò oggi invece, pur riconoscendo l’esigenza di porre in dialogo il quadro con l’ambiente esterno attraverso la materia, non prescinde dalla superficie della tela e dalla base cromatica.

L’Arte Informale nacque intorno alla metà del Ventesimo secolo come movimento di distacco dalla figurazione ma anche dall’emotività o dall’approccio psicologico di altre correnti dello stesso periodo. La scomposizione dell’immagine già avviatasi con il Futurismo e con il Cubismo trovò il suo culmine con l’Astrattismo, il Neoplasticismo, e il Suprematismo per i quali l’aderenza alla realtà osservata non contava, non doveva essere legata al visibile perché non era fondamentale per dar vita a un’opera d’arte, bensì il gesto plastico prescindeva da qualsiasi nozione visiva a cui lo sguardo fosse abituato. L’Informale Materico accolse le linee di base, i principi essenziali di queste avanguardie del primo ventennio del Novecento attraverso la rinuncia alla forma ma introducendo anche un’innovazione, quella cioè di inserire nella tela parti materiche, come plastiche, sabbie, legni, sacchi di juta, lamiere, schegge di vetro che non solo permisero di oltrepassare il confine della bidimensionalità dell’opera ma anche di reintrodurre all’interno della tela un’emotività, un pathos a cui in precedenza si era preferito rinunciare. Così le ferite e le bruciature delle opere di Alberto Burri, comunicavano direttamente con l’osservatore inducendolo a sentirsi quasi parte del sentire dell’autore, partecipando anche in virtù di quel fuoriuscire dei materiali che sembravano tendere verso l’esterno per superare il confine tra arte e quotidiano che avvicinavano il fruitore in virtù dell’inedita consapevolezza che un oggetto potesse trasformare il suo ciclo vitale divenendo altro ed entrando all’interno della fase creativa, dell’emotività dell’esecutore dell’opera. Altrettanto coinvolgimento è generato dai segni primordiali e al tempo stesso spirituali di Antoni Tapìes, in cui l’impeto non era tanto forte e intenso come quello del collega Burri bensì finalizzato alla riflessione, al lasciarsi avvolgere dal mistero segnico che svela, attraverso il contatto con il profondo, quelle sensazioni che emergono lentamente senza perdere la loro consistenza emozionale. I successivi passaggi artistici estremizzarono questi concetti e si fece strada la necessità di spostarsi sulla terza dimensione con lo Spazialismo e il Concettuale, l’uno interferente con la stessa tela per determinarne l’appartenenza a uno spazio, l’altro rinunciando completamente alla superficie di base per interagire direttamente con l’ambiente trasformando così in manifestazione artistica ogni oggetto o gesto appartenente al vivere quotidiano. L’artista pisana Lucia Pecchia oltrepassa e supera il distacco dalla forma, recuperando così il contatto con il visibile e con la realtà cromatica che appartiene a luoghi e a paesaggi esistenti o immaginati, mantenendo però una necessaria connessione con la materia, fondamentale per infondere vitalità, movimento e tendenza verso l’esterno, nelle sue coinvolgenti tele.

Il suo stile è sperimentale perché necessita di andare a scoprire di volta in volta oggetti e materiali introducibili nelle sue opere sulla base del concetto o del posto in cui colloca le sue riflessioni, i suoi ricordi o semplicemente i suoi sogni; si lascia andare a sensazioni terrene, ai piccoli e semplici piaceri della quotidianità Lucia Pecchia, esplicitando con immediatezza tutto ciò che appartiene all’immaginario comune, a quel desiderio di scoperta dell’inconoscibile dentro cui ciascun essere umano prima o poi si perde. L’interazione tra colore e materia è totale, completante, come se l’uno non potesse prescindere dall’altra e l’altra fosse condizione necessaria per dare spessore e consistenza all’immagine generata dalle tonalità scelte dall’artista e funzionali a raccontare il concetto o la sensazione che sente nel momento in cui si lascia andare all’atto creativo.

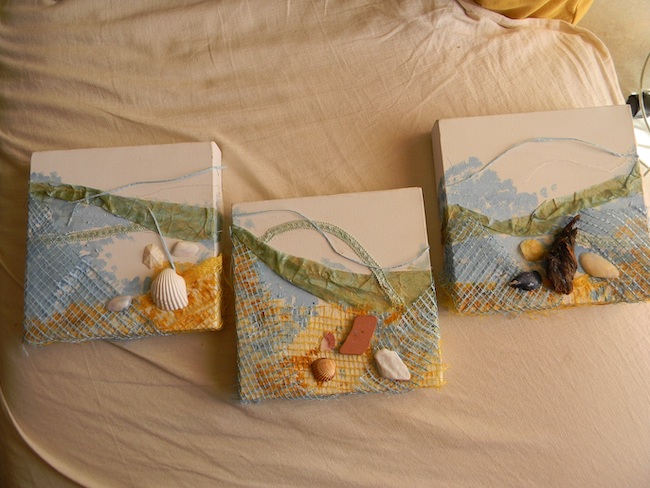

A volte Lucia Pecchia lascia trapelare ricordi, frammenti di vita appartenenti al passato ma ancora vividi nella sua interiorità per il senso di piacevolezza, di semplicità che hanno suscitato in lei e che ha sentito il desiderio di imprimere nella tela; nel trittico Passeggiata al mare 2 le tonalità chiare e solari di base fanno da sfondo agli elementi raccolti durante un giorno d’estate, le conchiglie e i sassi levigati si intrecciano a retine e pezzi di stoffa attraverso i quali l’artista definisce le onde e il confine tra acqua e sabbia. È evidente in quest’opera l’attenzione dell’artista al dettaglio, a quei frammenti in grado di attrarre la sua attenzione fino a divenire elementi fondamentali per la realizzazione dell’opera stessa, protagonisti di quel segmento di memoria grazie alla loro naturalezza e semplicità.

Nell’opera La vita invece, l’interrogazione della Pecchia si sposta su un tema più esistenziale, meno legato alla propria emozione e più orientato a esplorare quel mistero mai svelato che identifica il cammino di ciascun individuo ma anche quello dell’umanità più in generale, quell’alternarsi di alti e bassi, di cadute e discese, raccontate attraverso stralci di rete e di fili che si avvicendano in successione e che costituiscono l’essenza stessa del vivere; non solo, sottolineano anche quanto tutti i tasselli restino legati tra loro a comporre il puzzle del percorso personale, quanto ogni evento abbia una causa e un effetto che si concatena implementando l’evoluzione personale. Le tonalità chiare, basate sui bianchi e sulle gradazioni di verde, lasciano emergere il punto di vista positivo dell’artista, quella consapevolezza che tutto abbia un senso funzionale al passaggio verso il livello successivo, persino le circostanze meno piacevoli contengono in sé il seme per la comprensione, il superamento e la progressione.

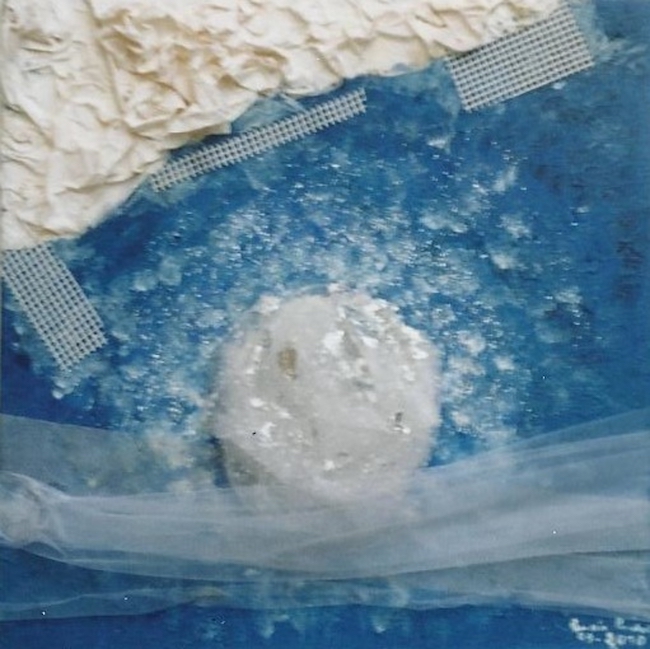

In La luna in un nastro di nebbia l’interrogazione si sposta verso il mistero di un astro che domina la quotidianità tanto quanto il sole, eppure in virtù del suo esistere nelle ore notturne, sembra non lasciarsi scoprire, sembra volersi mostrare parzialmente solo agli occhi di chi desidera andare oltre; la materia in quest’opera predomina sul colore, forse per dare solidità a quello che nell’immaginario comune sembra essere più un concetto, un pensiero legato al romanticismo, piuttosto che un elemento astronomico. Ecco dunque che il nastro di nebbia può rappresentare quella scia a cui l’uomo affida desideri e sogni, quella via lattea dentro la quale perdersi ammirati immaginando un domani migliore, più affine a tutto ciò che all’interno dell’emotività si nasconde.

Lo spazio, l’universo esercitano una particolare fascinazione in Lucia Pecchia, perché il suo desiderio di scoperta si spinge oltre e va verso le nebulose che racconta come esplosioni vivaci e colorate, piene di luce che riesce a squarciare il buio circostante, mettendo in evidenza l’atteggiamento comune all’essere umano di soffermarsi sulle ombre, sul negativo anziché provare ad avere una visione diversa, più propositiva e certa che tutto possa accadere, cambiare, colorarsi proprio in virtù di un punto di vista più positivo.

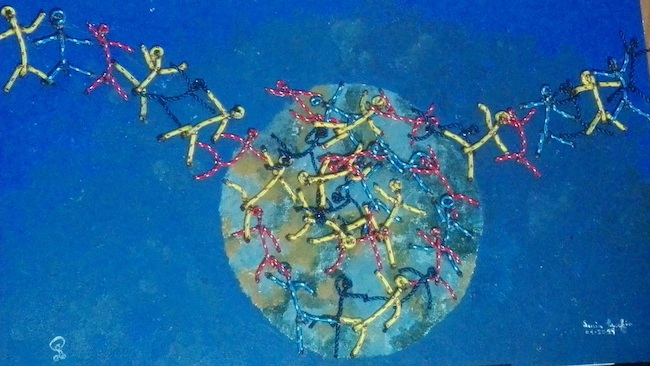

Esortazione che ha il suo culmine nell’opera L’uomo esce dal suo mondo, in cui la materia torna protagonista per descrivere un’umanità stilizzata che solo unendosi sarà in grado di cambiare le sorti del pianeta stesso e potrà modificare ciò che sembra inevitabilmente destinato a essere immodificabile. Lucia Pecchia è un’artista poliedrica, ama misurarsi con differenti declinazioni della sua creatività: disegna abiti, allestisce vetrine, crea oggettistica, vasi in terracotta, ha illustrato e realizzato la copertina di un libro. Nel corso della sua carriera ha partecipato a molte mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero – Varsavia, Barcellona, Parigi, Bruxelles, Budapest.

LUCIA PECCHIA-CONTATTI

Email: lucia.pecchia@virgilio.it

Sito web: https://www.pitturiamo.com/it/pittore-contemporaneo/lucia-pecchia-13959.html

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lucia.pecchia.1

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lucia.pecchia.1/

Lucia Pecchia, when colour cannot do without matter and vice versa

The need to go beyond two-dimensionality has been an important step in recent art history, generating a constant affirmation, often even a detachment, on the part of some artists from the boundaries delineated by the limiting surface of the canvas; many of them have decisively renounced staticness in order to make art in an innovative way, immersed in the surrounding space and then, in the exaggeration of the relevance of the object, detaching themselves completely from the pictorial base. The artist I am going to talk about today, on the other hand, while recognising the need to establish a dialogue between the painting and the external environment through matter, does not disregard the surface of the canvas and the chromatic base.

Informal Art was born around the middle of the twentieth century as a movement of detachment from figuration but also from the emotionality or psychological approach of other currents of the same period. The decomposition of the image, which had already begun with Futurism and Cubism, reached its peak with Abstractionism, Neoplasticism and Suprematism, for which adherence to observed reality was not important, it did not have to be linked to the visible because it was not fundamental to create a work of art, but rather the plastic gesture was independent of any visual notion to which the eye was accustomed. The Materic Informal embraced the basic lines, the essential principles of these avant-garde movements of the first twenty years of the twentieth century by renouncing form but also introducing an innovation, that of inserting material parts into the canvas, such as plastics, sand, wood, jute sacks, sheet metal and glass splinters, which not only made it possible to go beyond the two-dimensionality of the artwork but also to reintroduce into the canvas an emotionality, a pathos that had previously been renounced. Thus the wounds and burns in Alberto Burri’s artworks communicated directly with the observer, inducing him to feel almost part of the author’s feelings, participating also by virtue of the outflow of materials that seemed to tend outwards to cross the border between art and everyday life, bringing the observer closer by virtue of the unprecedented awareness that an object could transform its life cycle, becoming something else and entering the creative phase, the emotionality of the artwork’s creator. The same involvement is generated by the primordial and at the same time spiritual signs of Antoni Tapìes, in which the impetus was not as strong and intense as that of his colleague Burri, but aimed at reflection, at letting oneself be enveloped by the mystery of signs that reveal, through contact with the depths, those sensations that emerge slowly without losing their emotional consistency.

Subsequent artistic steps took these concepts to extremes and the need to move into the third dimension made itself felt with Spatialism and Conceptualism, one interfering with the canvas itself to determine its belonging to a space, the other completely renouncing the basic surface to interact directly with the environment, thus transforming every object or gesture belonging to everyday life into an artistic manifestation. Pisan artist Lucia Pecchia goes beyond and surpasses the detachment from form, thus recovering contact with the visible and with the chromatic reality that belongs to existing or imagined places and landscapes, while maintaining a necessary connection with the material, fundamental for infusing vitality, movement and a tendency towards the outside world into her engaging canvases. Her style is experimental because it requires her to discover objects and materials that can be introduced into her artworks on the basis of the concept or the place where she places her reflections, memories or simply her dreams; she lets herself go to earthly sensations, to the small and simple pleasures of everyday life Lucia Pecchia, making explicit with immediacy everything that belongs to the common imagination, to that desire to discover the unknowable within which every human being sooner or later loses himself. The interaction between colour and material is total, complete, as if one could not be separated from the other and the other was a necessary condition to give depth and consistency to the image generated by the shades chosen by the artist and functional to tell the concept or the sensation she feels in the moment she lets herself go to the creative act. At times Lucia Pecchia lets out memories, fragments of life belonging to the past but still vivid in her inner self because of the sense of pleasantness, of simplicity that they have aroused in her and that she has felt the desire to imprint on the canvas; in the triptych Passeggiata al mare 2 (Walk by the sea 2), the light, sunny tones of the base form the backdrop for the elements collected during a summer day, the shells and polished stones intertwined with nets and pieces of fabric through which the artist defines the waves and the borderline between water and sand.

The artist’s attention to detail is evident in this painting, to those fragments capable of attracting her attention to the point of becoming fundamental elements for the creation of the work itself, protagonists of that segment of memory thanks to their naturalness and simplicity. In the artwork La vita (Life), Pecchia’s questioning shifts to a more existential theme, less linked to her own emotions and more oriented towards exploring that never revealed mystery that identifies the path of each individual but also that of humanity in general, that alternation of highs and lows, of falls and descents, told through excerpts of net and threads that follow one another in succession and that constitute the very essence of living; not only that, they also emphasise how all the pieces remain linked together to make up the puzzle of the personal journey, how each event has a cause and an effect that interconnects, implementing personal evolution. The light tones, based on whites and shades of green, allow the artist’s positive point of view to emerge, that awareness that everything has a functional meaning for the passage to the next level, even the least pleasant circumstances contain within themselves the seed for understanding, overcoming and progression. In La luna in un nastro di nebbia (The moon in a ribbon of fog) the question moves towards the mystery of a star that dominates everyday life as much as the sun, yet because of its existence at night, it seems not to let itself be discovered, it seems to want to show itself partially only to the eyes of those who wish to go further; the material in this artwork predominates over the colour, perhaps to give solidity to what in the common imagination seems to be more of a concept, a thought linked to romanticism, rather than an astronomical element.

The ribbon of fog can therefore represent the trail to which man entrusts his desires and dreams, the milky way within which one can lose himself in admiration, imagining a better tomorrow, more akin to everything that is hidden within his emotions. Space and the universe are particularly fascinating to Lucia Pecchia, because her desire for discovery goes further and towards the nebulae she describes as lively and colourful explosions, full of light that manages to pierce the surrounding darkness, highlighting the common human attitude of dwelling on the shadows, on the negative instead of trying to have a different, more proactive vision, certain that everything can happen, change, become more colourful precisely because of a more positive point of view. This exhortation culminates in the work L’uomo esce dal suo mondo (Man comes out of his world), in which matter is once again the protagonist to describe a stylised humanity that only by uniting will be able to change the fate of the planet itself and modify what seems inevitably destined to be unchangeable. Lucia Pecchia is a multifaceted artist who loves to measure herself with different forms of creativity: she designs clothes, sets up shop windows, creates objects, terracotta vases, and has illustrated and created a book cover. During her career she has taken part in many group exhibitions in Italy and abroad – Warsaw, Barcelona, Paris, Brussels, Budapest -.