Nell’arte contemporanea è visibile spesso l’esigenza di un ritorno alle origini, di un legame con quel passato che può essere un punto fermo, un modo per oltrepassare e superare le incertezze di una realtà contemporanea a tratti destabilizzante, in altri invece talmente propulsiva verso la velocità e la routine tecnologica da indurre l’essere umano a dimenticarsi di riflettere su se stesso e ricordare da dove viene. Il protagonista di oggi sviluppa un personale stile in cui il segno delle sue origini berbere diviene la base per un dialogo con la propria interiorità e al contempo un modo per indurre l’osservatore a riflettere sull’essenza delle cose, senza lasciarsi distrarre da una forma esteriore.

Fin dai tempi più remoti l’uomo ha sempre avvertito l’esigenza di lasciare testimonianza scritta del proprio passaggio nella storia, anche quando il linguaggio non era ancora comprensibile ed era necessario ricorrere a segni per rappresentare una scena, una tradizione, un avvenimento rilevante che non doveva essere dimenticato; queste testimonianze erano incise sulla roccia e presero il nome di Graffiti proprio per la loro caratteristica di essere realizzate attraverso l’uso di scalpelli, chiodi, punteruoli od oggetti appuntiti. Ma ciò che contava era la necessità di esprimersi attraverso una primordiale forma d’arte che precedeva ogni altra forma di comunicazione, lasciando un inconsapevole messaggio che sarebbe divenuto testimonianza di quelle civiltà passate e che avrebbe ispirato, molti secoli dopo, un vero e proprio movimento artistico, il Graffitismo, dove gli artisti replicano lo scopo della loro arte, quello cioè di essere testimonianza dei tempi, di lanciare un messaggio alla società, di far sentire la propria voce altrimenti silenziosa. La Street Art si è andata affermando intorno alla seconda metà del Ventesimo secolo in quel territorio vasto e spesso alienante, gli Stati Uniti delle metropoli, proprio per divenire canale espressivo di persone ai margini che, malgrado il talento artistico e la forza dei contenuti, non avevano possibilità di accedere al sistema dell’arte, quello delle gallerie, dei musei e dei grandi critici. Dunque quello di esprimersi in modo istintivo e primordiale sui muri delle città era l’unico modo per gridare il proprio disagio, il senso di disadattamento e di rifiuto da parte di una società a cui non riuscivano ad appartenere; uno dei maggiori esponenti della Street Art degli anni Ottanta fu Jean-Michel Basquiat che si avvalse di quella pittura segnica e istintiva tipica degli antichi Graffiti e in virtù della quale è riuscito a emergere dando al suo stile un’immeditata riconoscibilità. Le linee semplici e di forte impatto raggiungevano l’osservatore con tutta la loro forza emotiva proprio per l’immediatezza del messaggio, e perché testimoniavano un sentire interiore, quella rabbia, quel malessere che aveva bisogno di fuoriuscire. La pittura segnica è stata utilizzata anche da molti esponenti dell’Arte Informale, come Franz Kline, Carla Accardi, Pierre Tal Coat, in cui la semplificazione dell’immagine era funzionale al messaggio interiore che in qualche modo, seppur a volte ingannevole per lo sguardo perché riconducibile a forme solo apparentemente conosciute, doveva indurre l’osservatore alla riflessione. Ma le iscrizioni segniche, quell’equilibrio a metà tra scrittura e rappresentazione figurativa dell’interiorità e delle tradizioni culturali, ha sempre contraddistinto anche la manifestazione artistica di culture lontane dal punto di vista del linguaggio ma vicine da quello geografico, come quelle dell’area del Mediterraneo in cui la scrittura stessa diveniva forma d’arte in virtù della sinuosità e della bellezza del tratto con cui era espressa in armonia con messaggi profondi e con simboli spirituali. È esattamente in questo contesto che si inserisce la produzione artistica di Massinissa Askeur, con origini berbere ma ormai da molti anni residente in provincia di Varese, a un passo dalla Svizzera, che trasforma la tradizione del suo popolo, i suoi usi e costumi, le sue credenze, per attualizzarle, per renderle affini a un vivere contemporaneo in cui non bisogna mai, sembra suggerire l’artista, dimenticare il passato più lontano che ha costituito quelle radici forti sulla base delle quali delineare il proprio carattere, la propria determinazione, il proprio desiderio di essere pienamente calati nell’attualità senza però mai tralasciare il luogo da cui si proviene.

L’essenzialità del segno grafico diviene così un mezzo attraverso il quale stimolare l’osservatore a riflettere, trovare un senso, un ordine tra le immagini che sembrano inserite a caso dall’artista ma che in realtà devono essere impulso di approfondimento, di meditazione per contrastare la corsa all’apparenza, quella superficialità che contraddistingue il vivere moderno.

Allo stesso modo delle incisioni di molti secoli fa, i segni di Massinissa Askeur evocano simboli, episodi, frammenti che vanno a comporre la sfaccettata realtà interiore ma anche quella esterna perché è in virtù degli accadimenti che tutto prende una direzione inaspettata eppure inevitabile per la crescita interiore; allo stesso tempo però non è possibile cancellare tutti quei passaggi che appartengono indissolubilmente non solo all’individuo bensì anche a tutto ciò a partire da cui egli stesso ha intrapreso il cammino di autoconoscenza.

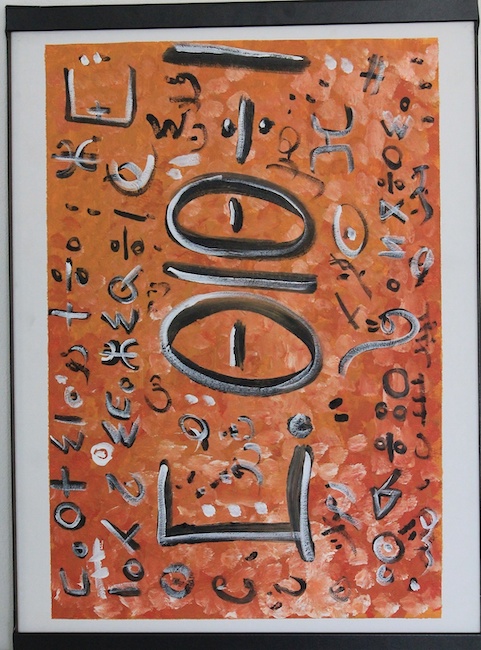

Nella tela Patrimoine (Patrimonio) l’artista usa le lettere della sua affascinante lingua berbera, quella dei Tuareg, per sottolineare l’importanza di mantenere il proprio patrimonio culturale dentro di sé esattamente come il suo popolo tradizionalmente nomade si aggrappa alle sue radici, le uniche facilmente trasportabili nei continui spostamenti; l’opera è metafora dell’uomo moderno che non dovrebbe mai cedere alla globalizzazione al punto di tralasciare l’importanza della memoria storica che gli appartiene, quella somma di usi, costumi, abitudini, che ciascuna persona dovrebbe sempre portare con sé, ovunque vada.

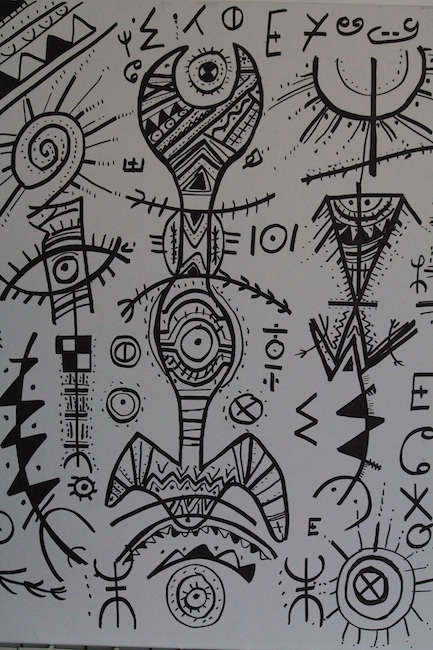

In Ancestrale infatti riproduce tutti quelli che sono i simboli religiosi, spirituali, in grado di rassicurare l’uomo sul suo destino, quelle forze superiori a cui l’essere umano si affida quando non riesce a intravedere un futuro che di fatto è inconoscibile; dunque la richiesta di essere protetto viene affidato alle potenti forze esterne, quelle in grado di esercitare il loro potere energetico per vegliare su chi si mette nelle loro mani. Il simbolo più evidente in quest’opera è l’occhio di Allah che allontana la negatività, dunque l’ancestrale del titolo evoca tutte quelle credenze, quella fede inspiegabile nei confronti di ciò che gli antenati hanno tramandato e che restano addosso all’individuo come una seconda pelle.

E ancora nel dipinto Theory of Relativity (Teoria della Relatività) Massinissa Askeur prende un concetto scientifico e lo trasporta verso il mondo dell’indefinito, dell’inspiegabile, dell’irrazionale, sostituendo le formule matematiche elaborate dal suo scopritore, Albert Einstein, con lettere berbere, aggiungendo forti emblemi scaramantici come la Mano di Fatima, potente amuleto in grado di scacciare l’invidia e le sue vibrazioni negative e limitanti, suggerendo all’osservatore che in fondo quella relatività di cui parlava il genio matematico può essere applicata a qualsiasi campo dell’esistenza, trasformandosi così in un credo filosofico che accetta il possibilismo, il non determinismo come opzione per accogliere tutto il costante cambiamento che nella vita sopraggiunge, per non ancorarsi a false certezze che dopo un attimo possono risultare già superate, errate o semplicemente non più appartenenti all’evolvere delle situazioni.

In tutto questo scorrere, le energie sottili, quelle inspiegabili forze che dominano a dispetto della resistenza dell’uomo ad accoglierle e lasciarsi andare a esse, costituiscono elemento fondamentale dell’esistenza perché in grado di modificare il punto di vista, di trasformare in maniera radicale il corso degli eventi a prescindere dalla volontà individuale di restare ostinatamente attaccati a punti fermi e opinioni spesso fuori luogo rispetto al fluire della vita. Studioso delle civiltà del Mediterraneo, della filosofia antica greco-romana e della storia, Massinissa Askeur ha una personalità poliedrica e dinamica in virtù della quale realizza progetti differenti contemporaneamente alla produzione e alla promozione della sua figura artistica; ha infatti creato una linea personale di orologi, Napoleon Watches, per la quale ha ricevuto un riconoscimento da parte del Consolato di Algeria di Milano. Partecipa regolarmente alle più importanti manifestazioni artistiche ricevendo premi e consensi dal pubblico e dalla critica.

MASSINISSA ASKEUR-CONTATTI

Email: massinissaaskeur@gmail.com

Sito web: https://massinissaaskeur.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/numidicus87

https://www.facebook.com/Askeurmassinissa

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/massinissa_askeur/

Massinissa Askeur’s sign painting, between graffiti and Berber culture to bring out the essence of things

Contemporary art often reveals a need to return to one’s origins, a link with the past that can be a fixed point, a way of overcoming the uncertainties of a contemporary reality that is sometimes destabilising and sometimes so driven by speed and technological routine that human being forget to reflect on himself and remember where he comes from. Today’s protagonist develops a personal style in which the sign of his Berber origins becomes the basis for a dialogue with his own interiority and at the same time a way to induce the observer to reflect on the essence of things, without letting himself be distracted by an external form.

From the earliest times man has always felt the need to leave written testimony of his passage through history, even when language was not yet comprehensible and it was necessary to use signs to represent a scene, a tradition, an important event that should not be forgotten; these testimonies were engraved on the rock and took the name of Graffiti precisely because of their characteristic of being made through the use of chisels, nails, awls or sharp objects. But what mattered was the need to express oneself through a primordial form of art that preceded any other form of communication, leaving an unconscious message that would become a testimony of those past civilisations and that would inspire, many centuries later, a true artistic movement, Graffitism, where artists replicate the purpose of their art, that is to be a testimony of the times, to send a message to society, to make their otherwise silent voice heard. Street Art became established around the second half of the 20th century in the vast and often alienating territory of the United States metropolis, precisely in order to become an expressive channel for people on the margins who, despite their artistic talent and the strength of their content, had no chance of accessing the art system, that of galleries, museums and major critics. Therefore, expressing themselves in an instinctive and primordial way on the walls of the cities was the only way to shout out their discomfort, their sense of maladjustment and rejection by a society to which they did not belong. One of the major exponents of Street Art in the 1980s was Jean-Michel Basquiat, who used the sign-like and instinctive painting typical of the old Graffiti artists, which enabled him to emerge, giving his style an immediate recognisability.

The simple, high-impact lines reached the observer with all their emotional force precisely because of the immediacy of the message, and because they testified to an inner feeling, that anger, that malaise which needed to escape. Sign painting was also used by many exponents of Informal Art, such as Franz Kline, Carla Accardi and Pierre Tal Coat, in which the simplification of the image was functional to the inner message that in some way, even if at times misleading to the eye because it can be traced back to forms that are only apparently known, had to induce the observer to reflect. But sign inscriptions, that balance between writing and figurative representation of the inner self and of cultural traditions, has always distinguished the artistic manifestation of cultures that are distant in terms of language but close in geographical terms, such as those in the Mediterranean area where writing itself became an art form by virtue of the sinuosity and beauty of the line with which it was expressed in harmony with profound messages and spiritual symbols. It is precisely in this context that the artistic production of Massinissa Askeur, of Berber origin but now living for many years in the province of Varese, just a stone’s throw from Switzerland, fits. He transforms the traditions of his people, their customs and beliefs, to bring them up to date, to make them akin to contemporary living in which we must never, seems to be suggesting the artist, that we should never forget the more distant past, which constitutes the strong roots on the basis of which one can define his character, his determination and his desire to be fully integrated into the present, without ever forgetting where one comes from.

The essentiality of the graphic sign thus becomes a means of stimulating the observer to reflect, to find meaning, an order among the images that seem to have been inserted at random by the artist but which in reality must be an impulse for in-depth study, of meditation to counter the race to appearances, the superficiality that characterises modern life. In the same way as the engravings of many centuries ago, Massinissa Askeur’s signs evoke symbols, episodes and fragments that compose the multifaceted inner and outer reality, because it is by virtue of events that everything takes an unexpected but inevitable direction for inner growth. At the same time, however, it is not possible to erase all those passages that belong indissolubly not only to the individual but also to everything from which he has embarked on the path of self-knowledge. In the canvas Patrimoine (Heritage), the artist uses the letters of his fascinating Berber language, that of the Tuareg, to underline the importance of keeping one’s own cultural heritage within oneself, just as his traditionally nomadic people cling to their roots, the only ones that are easily transportable in their constant movements. The artwork is a metaphor for modern man, who should never give in to globalisation to the point of neglecting the importance of his own historical memory, the sum total of customs and habits that each person should always carry with him wherever he goes. In Ancestrale (Ancestral), in fact, he reproduces all the religious and spiritual symbols capable of reassuring man about his destiny, those higher forces to which the human being relies when he cannot glimpse a future that is in fact unknowable; thus the request to be protected is entrusted to powerful external forces, those capable of exercising their energetic power to watch over those who place themselves in their hands.

The most obvious symbol in this artwork is the eye of Allah, which banishes negativity, so the ancestral of the title evokes all those beliefs, that inexplicable faith in what the forefathers have handed down and which remain on the individual like a second skin. And again, in the painting Theory of Relativity, Massinissa Askeur takes a scientific concept and transports it into the world of the indefinite, the inexplicable, the irrational, replacing the mathematical formulas developed by its discoverer, Albert Einstein, with Berber letters, adding strong superstitious emblems such as the Hand of Fatima, a powerful amulet capable of chasing away envy and its negative and limiting vibrations, suggesting to the observer that, after all, the relativity of which the mathematical genius spoke can be applied to any field of existence, thus transforming itself into a philosophical creed that accepts possibilism, non-determinism as an option for accepting all the constant changes that occur in life, so as not to anchor oneself to false certainties that after a moment may already be outdated, mistaken or simply no longer belonging to the evolution of situations. In all this flowing, the subtle energies, those inexplicable forces that dominate in spite of man’s resistance to accept them and let himself go to them, constitute a fundamental element of existence because they are able to change the point of view, to radically transform the course of events regardless of the individual’s will to stubbornly stick to fixed points and opinions that are often out of place in relation to the flow of life. A scholar of Mediterranean civilisations, ancient Greco-Roman philosophy and history, Massinissa Askeur has a multifaceted and dynamic personality, which enables him to carry out different projects at the same time as producing and promoting his art. He has created a personal line of watches, Napoleon Watches, for which he has received recognition from the Algerian Consulate in Milan. He regularly takes part in the most important artistic events, receiving awards and acclaim from the public and the critics.