Il legame con il passato rappresenta l’approccio meditativo e riflessivo per tutta quella categoria di artisti che ritengono fondamentale attingere proprio agli insegnamenti degli avi e alla cultura più antica per avere una panoramica più chiara del presente; soprattutto perché osservare ciò che era importante o temuto tanti secoli permette di evidenziare un corso e ricorso sempre attuale se solo si avesse la lucidità e la capacità di approfondimento di osservarne i risvolti più nascosti. Ecco dunque che raccontare quei miti e leggende di altre epoche può aiutare l’uomo moderno a scoprire quante siano le similitudini tra i dubbi esistenziali di oggi e quelli espressi più poeticamente attraverso la narrazione mitologica. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi sceglie uno stile pittorico fortemente figurativo ed evocativo per ricordare all’osservatore quanto sia importante il legame con le origini culturali per attraversare la lunga strada del presente.

Verso la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo si concretizzò nei salotti artistici europei l’esigenza di orientarsi verso l’essere umano, il sentire emozionale declinato in varie modalità espressive sulla base delle tendenze esecutive degli autori delle opere; da un lato infatti vi fu un rifiuto netto dell’armonia estetica e delle regole della pittura tradizionali per porre l’accento in maniera più incisiva sulla predominanza di tutte quelle sensazioni troppo a lungo escluse dall’arte precedente, accademica e troppo concentrata sulla fedeltà alla realtà narrata, che sfociò nell’Espressionismo. Dall’altro un approccio più equilibrato dal punto di vista figurativo ma esplorativo nei confronti dei significati, di quelle energie sottili, di quei misteri da sempre presenti nell’esistenza umana ma ignorati perché troppo indecifrabili e incomprensibili diedero vita al Simbolismo che si rivelò essere un anello di congiunzione tra l’intuito anticipatore di Hieronymus Bosch e il seguente orientamento verso il subconscio e l’inquietudine del Surrealismo. Gli artisti appartenenti a questa corrente prendevano letteralmente per mano l’osservatore conquistandolo con immagini che poteva riconoscere, ma poi lo conducevano verso l’esplorazione di significati più profondi, a metà tra credenze religiose, simboli antichi e interazione dell’essere umano con la natura infondendo nelle opere una sensazione di inspiegabile, di spirituale che sfuggiva al controllo della razionalità. Con stile pittorico fortemente classico Gustave Moreau rivisitò miti e icone bibliche, ma anche pagane, mantenendo una spiccata tendenza al Naturalismo attraverso cui realizzò dipinti di grande impatto dove metteva in risalto il soprannaturale fuso con la realtà, come se le sue atmosfere appartenessero a una terra di mezzo in cui tutto poteva essere possibile, esattamente come raccontato nelle antiche leggende. Allo stesso modo, o forse in maniera persino più evidente, Arnold Böcklin si occupò di interpretare attraverso la sua lente esplorativa, quei simboli epici appartenenti all’immaginario comune e tramandati nei secoli proprio per la loro funzione etica ma anche per la caratteristica di indecifrabilità che apparteneva loro; non solo, nelle sue opere maggiori come L’isola dei morti, riuscì a far emergere quel non detto, quella naturale curiosità dell’uomo nei confronti dell’alternanza tra la vita e la morte che, pur appartenendo all’evoluzione della vita, non riusciva a essere spiegata e affrontata dal punto di vista spirituale se non attraverso la religione oppure, nel suo caso, l’arte. Tanto tenebroso fu l’approccio pittorico di Böcklin quanto invece più decorativo, delicato e luminoso fu quello della fase matura di Odilon Redon, in cui la natura e l’alchimia dell’irrealtà erano base di tutta la produzione pittorica.

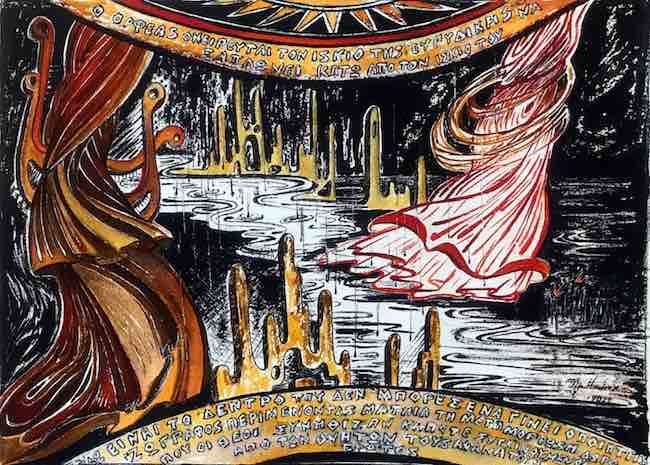

L’artista greca Olga Barmazi attualizza il Simbolismo di fine Ottocento e lo reinterpreta introducendo elementi e tradizioni appartenenti all’antica cultura del suo paese, culla della grande filosofia e delle leggende legate agli dei che dominavano le città e determinavano le vicende umane; allo stesso modo la vicinanza alla natura e alla sua purezza non possono non entrare all’interno delle sue tele che si trasformano in mezzo di ascolto, di attenzione nei confronti di quei sussurri, quei respiri che affiancano costantemente la vita dell’essere umano e che ne accompagnano ogni singolo passo evolutivo.

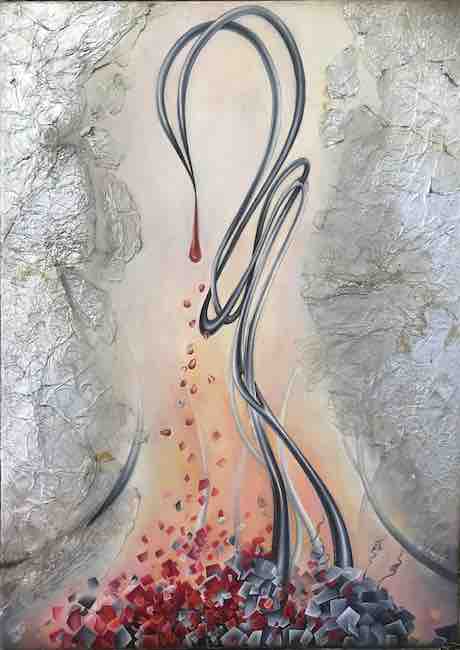

Lo stile pittorico è fortemente figurativo ma mentre in alcune tele è più tradizionale sia dal punto di vista cromatico che da quello esecutivo, in altre invece tende verso l’Espressionismo soprattutto per la linea netta del disegno che si amplia persino ai colori utilizzati infondendo la sensazione che ci si trovi davanti a opere grafiche, le stesse che utilizza nel suo lavoro di illustratrice di libri per bambini; e poi, in alcuni dipinti in cui il concetto deve sovrastare l’immagine, tende verso una stilizzazione vicina all’Astrattismo, quello sottile e delicato attraverso il quale racconta quanto la riflessione e il pensiero semplifichino a volte ciò che sembra complicato solo perché l’essere umano non è capace di andare verso l’essenza.

Il dipinto Fenice Eros appartiene esattamente a questo ciclo di opere in cui il significato viene spogliato da tutto ciò che sarebbe superfluo e così Olga Barmazi evidenzia la passionalità dell’animale mitologico in grado di rinascere dalle proprie ceneri che qui sono rappresentate come ferite, tagli sanguinanti non ancora risanati mentre ciò che invece è urgente è la necessità di ricominciare a risalire, a risorgere malgrado la difficoltà di lasciarsi alle spalle gli accadimenti. Lo sfondo è in foglia argento per indicare che intorno c’è la luce, che al di là dell’ostacolo c’è la capacità di superarlo ricominciando a camminare verso una nuova strada; è un’allegoria della vita dell’essere umano quella dell’artista che mostra un approccio positivo, forte e determinato in grado di trapelare dall’opera e di trasformarsi in esortazione nei confronti dell’osservatore ad avere un approccio simile perché in fondo è quello migliore per evolvere e trovare un senso a tutto ciò che si verifica.

In ognuna delle tele della Barmazi emerge un significato profondo, nascosto, quell’inspiegabile legato alla spiritualità oggettiva che appartiene a tutto ciò che ruota intorno all’uomo e che solo attraverso l’attento ascolto dell’artista riesce a trovare voce; anche quando rivolge la sua attenzione alla natura manifesta una predisposizione a farsi interprete dei respiri e dei sussurri che dai luoghi narrati sembrano fuoriuscire, come se in qualche modo attraverso il filtro della sua sensibilità riuscisse a creare l’atmosfera migliore per lasciar emergere il senso nascosto nella naturalezza che spesso viene trascurato dall’uomo contemporaneo.

In Santità anonima i fiori protagonisti appartengono a un regno irreale, mistico, da cui emerge tutta la magia della delicatezza poetica che si riceve prestando attenzione all’impalpabilità della natura, di quel mondo pulsante ma silenzioso che vibra delle energie dell’universo e che accompagna come in una danza la vita umana. In questa tela lo sfondo è notturno, probabilmente sotto la luce della luna piena che illumina gli steli e le corolle trasformandoli in fili d’argento, ed è proprio in quel contesto che l’artista riesce a catturare l’attenzione dell’osservatore, senza aggredirlo, senza alzare la voce bensì semplicemente conducendolo per mano nella magia di un punto di vista diverso, meno distratto.

Ma il Simbolismo più incisivo si concretizza quando Olga Barmazi unisce i miti antichi e le leggende e la sua forte inclinazione alla figurazione le consente di andare a indagare oltre il primo impatto di ciò che lo sguardo vede, di spingere il fruitore a fare i conti con i propri interrogativi, con le proprie perplessità e capacità di approfondimento, lasciandosi guidare verso sfaccettature da esplorare, da osservare con curiosità e apertura all’ascolto; questo è quanto emerge dal dipinto Libero arbitrio in cui Dio sta invitando Adamo, allo stesso modo che nell’affresco di Michelangelo, a compiere la scelta che si rivelerà fatale, quella che determinerà la caduta. Non c’è esitazione in quel gesto ma si preannuncia già l’esito finale, quello che indurrà lui ed Eva a precipitare sulla terra, la cui immagine è ispirata allo sfondo della Monna Lisa di Leonardo Da Vinci, dando di fatto inizio all’umanità. La capacità evocativa di Olga Barmazi si mescola al significato profondo di un gesto tanto importante, eppure non si percepisce giudizio bensì semplicemente la narrazione e l’attenzione verso il significato di quell’antico mito.

7 Leda Nemesis e Cygnus

Olga Barmazi, scrittrice, illustratrice di libri per bambini e responsabile dei laboratori di pittura per bambini e adulti presso l’Apothiki Technon, di cui è fondatrice, e la Kaloy Foundation for Arts and Culture di Corinto, città in cui vive e lavora, ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre collettive in Europa, Usa, Giappone e Australia, ha ricevuto premi e riconoscimenti negli Stati Uniti e in Giappone. Ha recentemente esposto presso la Medina Art Gallery di Roma.

OLGA BARMAZI-CONTATTI

Email: olgabarmazi@yahoo.gr

Sito web: https://olgabarmazi.wixsite.com/website

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/BARMAZIAGGOLGA

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/olgabarmazi/

Olga Barmazi’s Symbolism, between Greek mythology and the breath of nature

The link with the past represents the meditative and reflective approach for that whole category of artists who consider it fundamental to draw precisely on the teachings of their ancestors and the most ancient culture in order to have a clearer overview of the present; above all because observing what was important or feared so many centuries ago can highlight a course and recourse that is always current if only one had the lucidity and capacity for in-depth study to observe its most hidden implications. Thus, recounting those myths and legends from other eras can help modern man discover how many similarities there are between today’s existential doubts and those expressed more poetically through mythological narration. The artist I am going to tell you about today chooses a strongly figurative and evocative style of painting to remind the observer how important is the link with cultural origins to traverse the long road of the present.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the European art salons saw the need to focus on the human being, on emotional feelings expressed in various ways according to the executive tendencies of the artists. On the one hand, there was a clear rejection of aesthetic harmony and the traditional rules of painting in order to place a more incisive emphasis on the predominance of all those sensations that had been excluded for too long by the previous academic art that was too focused on faithfulness to the reality narrated, which led to Expressionism. On the other hand, a more figuratively balanced but exploratory approach to meanings, to those subtle energies, those mysteries that have always been present in human existence but ignored because they were too indecipherable and incomprehensible, gave rise to Symbolism, which proved to be a link between the anticipatory intuition of Hieronymus Bosch and the following orientation towards the subconscious and the restlessness of Surrealism. The artists belonging to this current literally took the observer by the hand, captivating him with images that he could recognise, but then leading him towards the exploration of deeper meanings, somewhere between religious beliefs, ancient symbols and the interaction of the human being with nature, infusing the artworks with a feeling of the inexplicable, the spiritual that was beyond the control of rationality. With a strongly classical pictorial style, Gustave Moreau revisited biblical myths and icons, but also pagan ones, maintaining a marked tendency towards Naturalism through which he produced paintings of great impact where he emphasised the supernatural fused with reality, as if his atmospheres belonged to a middle ground where everything could be possible, exactly as recounted in ancient legends.

Similarly, or perhaps even more clearly, Arnold Böcklin was concerned with interpreting, through his exploratory lens, those epic symbols belonging to the common imagination and handed down through the centuries precisely because of their ethical function but also because of the characteristic of indecipherability that belonged to them; not only that, in his major works such as The Isle of the Dead, he succeeded in bringing out that unspoken, that natural human curiosity about the alternation between life and death which, although belonging to the evolution of life, could not be explained and addressed from a spiritual point of view except through religion or, in his case, art. As gloomy was Böcklin’s pictorial approach as Odilon Redon’s one in his more mature stage was more decorative, delicate and luminous, in which nature and the alchemy of unreality were the basis of all painting. The Greek artist Olga Barmazi updates late 19th century Symbolism and reinterprets it by introducing elements and traditions belonging to the ancient culture of her country, the cradle of great philosophy and legends linked to the gods who dominated cities and determined human affairs; similarly, the closeness to nature and its purity cannot fail to enter into her canvases, which are transformed into a means of listening, of paying attention to those whispers, those breaths that constantly flank the life of the human being and that accompany every single evolutionary step. The pictorial style is strongly figurative, but while in some canvases it is more traditional in terms of both colour and execution, in others it tends towards Expressionism, especially in the stark lines of the drawing, which even extends to the colours used, giving the impression to be in front of graphic works, the same ones she uses in her work as a children’s book illustrator; and then, in some paintings in which the concept must dominate the image, she tends towards a stylisation close to Abstractionism, the subtle and delicate one through which she recounts how reflection and thought sometimes simplify what seems complicated only because the human being is unable to go towards the essence.

The painting Phoenix Eros belongs precisely to this cycle of artworks in which the meaning is stripped of everything that would be superfluous and thus Olga Barmazi highlights the passion of the mythological animal capable of rebirth from its own ashes which here are represented as wounds, bleeding cuts not yet healed while what is instead urgent is the need to re-start, to rise again despite the difficulty of leaving events behind. The background is made of silver leaf to indicate that there is light all around, that beyond the obstacle there is the ability to overcome it by starting to walk again towards a new road; it is an allegory of the life of the human being that of the artist who shows a positive, strong and determined approach that can seep out of the artwork and turn into an exhortation to the observer to have such an approach because after all it is the best one to evolve and find a sense in everything that occurs. In each of Barmazi’s canvases, a profound, hidden meaning emerges, that inexplicable linked to the objective spirituality which belongs to everything that revolves around man and that can only find a voice through the artist’s attentive listening; even when she turns her attention to nature, she manifests a predisposition to interpret the breaths and whispers that seem to escape from the places narrated, as if somehow through the filter of her sensitivity she manages to create the best atmosphere to allow the meaning hidden in the naturalness that is often overlooked by contemporary man to emerge. In Anonymous Holiness, the protagonist flowers belong to an unreal, mystical realm, from which emerges all the magic of the poetic delicacy that one receives by paying attention to the impalpability of nature, of that pulsating but silent world that vibrates with the energies of the universe and accompanies human life as in a dance. In this canvas the background is nocturnal, probably under the light of the full moon that illuminates the stems and corollas transforming them into silver threads, and it is precisely in that context that the artist succeeds in capturing the observer’s attention, without attacking him, without raising the voice but simply leading him by the hand into the magic of a different, less distracted point of view.

But the most incisive Symbolism is realised when Olga Barmazi combines ancient myths and legends, and her strong inclination towards figuration allows her to go beyond the first impact of what the eye sees, to push the observer to come to terms with his own questions, perplexities and capacity for in-depth analysis, letting himself be guided towards facets to be explored, to be watched with curiosity and openness to listening; this is what emerges from the painting Free Will in which God is inviting Adam, in the same way as in Michelangelo’s fresco, to make the choice that will prove to be fatal, the one that will determine the fall. There is no hesitation in that gesture but the final outcome is already announced, the one that will induce him and Eva to fall to earth, whose image inspired by the background of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, effectively starting humanity.. Olga Barmazi’s evocative ability is mixed with the profound meaning of such an important gesture, yet one does not perceive judgement but simply narration and attention to the meaning of that ancient myth. Olga Barmazi, writer, illustrator of children’s books and head of painting workshops for children and adults at Apothiki Technon, of which she is a founder, and the Kaloy Foundation for Arts and Culture in Corinth, the city where she lives and works, has participated in group exhibitions in Europe, USA, Japan and Australia, and has received prizes and awards in the United States and Japan. She recently exhibited at the Medina Art Gallery in Rome.