Esistono tematiche che da sempre esercitano un fascino magnetico sugli artisti, perché spesso inspiegabili e inafferrabili e per questo oggetto di indagine, di riflessione che si manifesta attraverso linguaggi interpretativi differenti, spesso opposti tra loro ma che inevitabilmente convergono sull’accettazione dell’impossibilità di cogliere una realtà assoluta o di stabilire una spiegazione universalmente corretta, giusta. Di conseguenza i quesiti e i concetti continuano a prestarsi a essere decifrati e osservati dalle varie sfaccettature e accordandosi all’approccio pittorico di ciascun creativo che però sa perfettamente di poter dare una risposta solo parzialmente reale o attendibile, immergendosi così nel mondo delle infinite possibilità. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi sceglie uno stile fortemente legato alla figurazione pur entrando in un mondo parallelo fatto di significati profondi, da esplorare e decodificare a seconda del punto di vista di chi si pone davanti alle sue tele.

A partire dai primi anni del Novecento cominciò a emergere negli artisti dell’epoca l’esigenza di porsi in contatto con l’interiorità, con le proprie emozioni ma anche con le riflessioni e le paure che affioravano in modo via via più incisivo a causa dei venti di guerra e dell’alienazione dell’essere umano a fronte sia del veloce e rapido progresso tecnologico che spersonalizzava il lavoratore rendendolo parte di una catena di montaggio, e sia delle atrocità vissute durante il conflitto mondiale, il primo, che aveva privato le persone di mogli, mariti, figli, genitori e dunque delle certezze costruite fino a quel momento. Fu proprio il grande neurologo e psicoanalista Sigmund Freud a studiare i meandri dell’inconscio analizzando e aiutando militari di ritorno dai campi di battaglia a guerra finita affetti da sindrome post-traumatica, scoprendo che tutti i fantasmi che impedivano loro di condurre una vita normale si affollavano nell’inconscio e nella dimensione onirica; e fu proprio ispirandosi agli studi del grande Freud che il Surrealismo segnò le sue linee guida che intendevano rappresentare e portare alla luce attraverso l’arte tutto ciò che abitualmente veniva soffocato dalla mente cosciente, quei turbamenti, quegli incubi che emergevano quando l’individuo si trovava solo con se stesso. Le opere di Salvador Dalì erano testimonianza di un mondo distorto, popolato di creature inquietanti, di concetti ripetuti e ossessionanti come il tempo, la sessualità, costituito da scenari desolati e sinistri spesso privi della presenza umana; così come invece quelle di Max Ernst tendevano verso mondi apocalittici costituiti da entità mostruose appartenenti al regno degli incubi, a metà tra esseri umani e terrificanti mutanti, a sottolineare quanto la mente nella sua dimensione più inconscia fosse in grado di concretizzare fantasmi interiori e paure. E poi René Magritte, la cui pittura meno angosciante rivolgeva invece l’attenzione alle sottili energie della realtà che giungono all’individuo inducendolo a meditare sui significati stessi dell’esistenza, sul senso della vita e di tutto ciò che la compone. L’artista romano Sergio Alessandrini mostra un approccio più vicino all’esplorazione meditativa e sottile di Magritte piuttosto che all’universo dell’incubo inquietante e ossessivo di Dalì o Ernst, manifestandosi nel suo caso attraverso concetti per lui essenziali, come quello del tempo o l’apparente delicatezza della natura, come i fiori, che nei suoi lavori mostrano in realtà tutta la loro forza.

Ma soprattutto ciò che ama raccontare l’artista è la costante metafora dell’uomo contemporaneo esplorata da molteplici punti di vista, le inquietudini, le illusioni, le certezze così come le insicurezze inespresse che tuttavia non possono fare a meno di essere osservate ed esplicate attraverso le sue opere pittoriche o ad acquerello con un tocco delicato che sembra elevare ciascun concetto a un livello empirico perché sfuggente a ogni rigida regola o a ogni tentativo di afferrarlo attraverso la razionalità.

Da un punto di vista puramente stilistico l’approccio di Alessandrini è fortemente figurativo e concreto ma è esattamente da quel legame con l’immagine conosciuta che diventa possibile creare scenari paralleli che l’occhio conosce ma da cui un attimo dopo viene attratto per la loro irrealtà; eppure la sostanza dei pensieri espressi è fortemente legata all’uomo, a un’essenza che gli appartiene malgrado la sua tendenza a nasconderla, e si manifesta davanti all’osservatore sotto forma di allegoria che in prima battuta lo incuriosisce e poi, in un secondo momento, lo aiuta a riflettere, a compiere un percorso introspettivo all’interno di se stesso guidato dalle immagini apparentemente reali dell’artista.

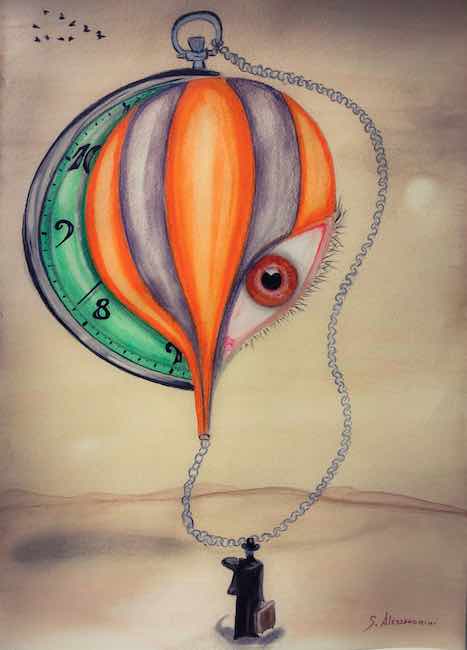

Uno dei temi principali della produzione di Sergio Alessandrini è il tempo, un elemento fondamentale della vita contemporanea di cui però l’essere umano tende a perdere il senso reale, credendolo infinito, recuperabile, rivivibile senza comprendere che invece tutto ciò che è possibile fare è afferrarlo e viverlo nel presente, prima che sia troppo tardi, senza aspettare di dover rimpiangere ciò che non si è colto.

Questo tipo di approccio emerge chiaramente dalla tela La percezione del tempo dove l’artista esplora varie sfaccettature, vari punti di vista su come affrontare l’elemento più sfuggevole e ne racconta il tentativo vano di catturarlo scoprendone il segreto, costituito dalla serratura di cui non si scorge la chiave; al tempo stesso ne evidenzia l’illusione, quella superficie in vetro che infonde la sensazione di un’illimitatezza che però di fatto viene immediatamente sovvertita dal riquadro dentro cui è collocata, tanto quanto le due finestre ai lati della composizione si affacciano su cifre ripetute che sembrano costituire un monito per l’essere umano e per l’osservatore, un suggerimento a non lasciare che i numeri si susseguano senza averne impiegato lo scandire.

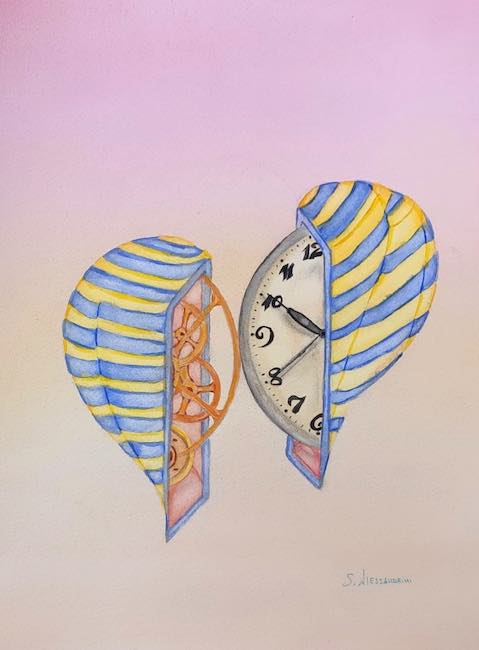

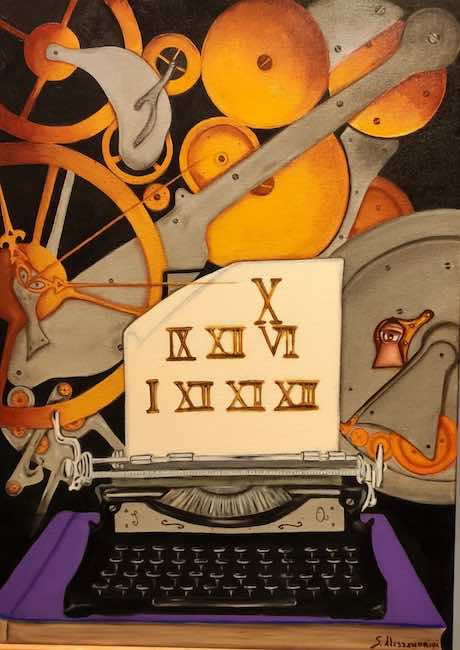

E ancora nel dipinto L’inganno Alessandrini affronta il tema dell’utopia dell’immortalità, di quella convinzione dell’uomo di poter essere eterno salvo poi fare i conti con l’evidenza di essere parte di un meccanismo, rappresentato dagli ingranaggi dello sfondo, del quale è più vittima che non protagonista, arrogantemente convinto di poter gestire l’ingestibile essendo invece solo un granello all’interno delle forze universali che muovo il mondo. L’artista suggerisce che solo attraverso la cultura, quella che oltrepassa il tempo e i secoli, è possibile lasciare una traccia di sé, trovare l’eternità che si concretizza solo nel caso in cui si riesce a uscire dagli schemi della società e a parlare con una voce solista, quella della scrittura che può ridimensionare con la sua solennità la sensazione di falsa immortalità in cui l’uomo contemporaneo, con tutta la sua attenzione alle cose più superficiali e vacue, crede di vivere.

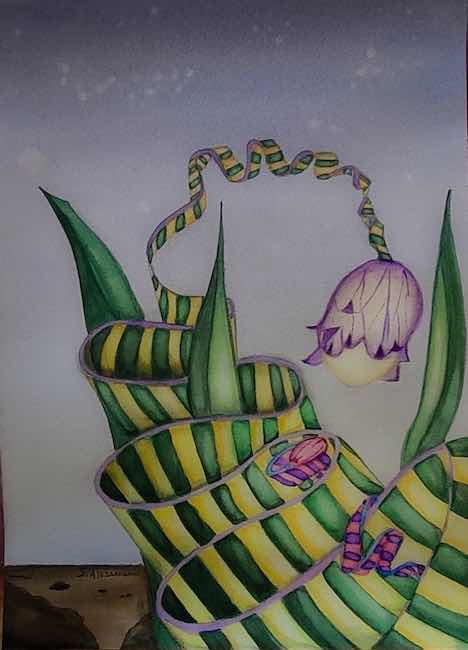

Dunque Sergio Alessandrini non può fare a meno di evidenziare le gabbie dentro cui la modernità tende a chiudere l’essere umano, inducendolo ad accettare rinunce e limitazioni in nome di una conformazione alla società troppo spesso tendente a uniformare l’individuo senza rispettarne le specificità; l’opera Il tulipano e la farfalla parla esattamente di questo, di un appiattimento generato dalle catene con cui spesso l’uomo moderno si intrappola, fatte di regole, di dettami, di leggi non scritte che entrano sottilmente nella vita e si avvolgono a essa generando di fatto un ingrigimento, un distacco dalla propria essenza che si propaga alla collettività. La farfalla rappresenta dunque la libertà, quella rara voce fuori dal coro in grado di sovvertire l’ordine delle cose in virtù della sua scelta di potersi elevare e distaccarsi dalle catene da cui tutto è avvolto e, attraverso la sua colorata leggerezza, può salvare anche chi sente il disagio di quella conformità, di quell’adeguamento a qualcosa di diverso dalla sua essenza.

Diverse sono le tecniche sperimentate da Sergio Alessandrini per narrare il suo mondo fatto di simboli e di significati nascosti, passa infatti dall’olio su tela alla tecnica mista all’acquarello su carta cotone, per mantenere la libertà di scegliere il mezzo espressivo più affine all’emozione o alla meditazione del momento in cui si appresta a creare, senza però mai tralasciare l’intensità espressiva, la tendenza ad approfondire tutte quelle sensazioni, tutti quei pensieri che attraversano la quotidianità e che spesso vengono lasciati sfuggire senza soffermarvisi. Alessandrini invece li rende protagonisti assoluti della sua riflessione e ne attraversa le pieghe più nascoste; l’artista ha cominciato a esporre solo recentemente i suoi lavori riscuotendo un ottimo successo di pubblico e interesse da parte della critica.

SERGIO ALESSANDRINI-CONTATTI

Email: sergioalessandrini79@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sergio.alessandrini.568

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lameccanicadellinconscio/

Journey into the world of the unconscious between illusion of time and awareness of fragility with Metaphysical Surrealism by Sergio Alessandrini

There are themes that have always exerted a magnetic fascination on artists, because they are often inexplicable and elusive, and for this reason they are the object of investigation, of reflection that manifests itself through different interpretative languages, often opposing each other but inevitably converging on the acceptance of the impossibility of grasping an absolute reality or of establishing a universally correct, right explanation. Consequently, the questions and concepts continue to lend themselves to being deciphered and observed from various facets and tuned to the pictorial approach of each creative artist, who, however, knows perfectly well that can only give a partially real or reliable answer, thus plunging into the world of infinite possibilities. The artist I am going to tell you about today chooses a style strongly linked to figuration while entering a parallel world made up of profound meanings, to be explored and decoded depending on the point of view of those who stand before his canvases.

Starting in the early years of the 20th century, began to emerge the need in the artists of the time to get in touch with their inner selves, with their emotions, but also with the reflections and fears that were surfacing more and more incisively due to the winds of war and the alienation of the human being in the face of both the fast and rapid technological progress that depersonalised the worker by making him part of an assembly line, and also of the atrocities experienced during the First World War, which had deprived people of wives, husbands, children, parents and thus of the certainties built up until then. It was the great neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud who studied the meanders of the unconscious by analysing and helping soldiers returning from the battlefields after the war was over and suffering from post-traumatic syndrome, discovering that all the ghosts that prevented them from leading a normal life crowded into the unconscious and dream dimension; and it was by drawing inspiration from the studies of the great Freud that Surrealism marked out its guidelines that intended to represent and bring to light through art all that was usually stifled by the conscious mind, those disturbances, those nightmares that emerged when the individual was alone with himself.

Salvador Dali’s artworks bore witness to a distorted world, peopled by disturbing creatures, repeated and obsessive concepts such as time and sexuality, made up of desolate and sinister scenarios often devoid of human presence. Similarly, Max Ernst’s works tended towards apocalyptic worlds made up of monstrous entities belonging to the realm of nightmares, halfway between human beings and terrifying mutants, underlining how much the mind in its most unconscious dimension was capable of concretising inner phantasms and fears. Then there was René Magritte, whose less distressing painting turned its attention to the subtle energies of reality that reach the individual, inducing him to meditate on the very meanings of existence, on the meaning of life and everything that makes it up. Roman artist Sergio Alessandrini shows an approach closer to the meditative and subtle exploration of Magritte than to the universe of the disturbing and obsessive nightmare of Dali or Ernst, manifesting itself in his case through concepts that are essential to him, such as that of time or the apparent delicacy of nature, such as flowers, which in his artworks actually show all their strength.

But above all, what the artist likes to tell us about is the constant metaphor of contemporary man explored from multiple points of view, the anxieties, illusions, certainties as well as unexpressed insecurities that nevertheless cannot help but be observed and explained through his pictorial or watercolour works with a delicate touch that seems to elevate each concept to an empirical level because it eludes any rigid rule or any attempt to grasp it through rationality. From a purely stylistic point of view, Alessandrini’s approach is strongly figurative and concrete, but it is precisely from that link with the known image that it becomes possible to create parallel scenarios that the eye is familiar with but to which it is attracted by their unreality a moment later; yet the substance of the thoughts expressed is strongly linked to man, to an essence that belongs to him despite his tendency to conceal it, and it manifests itself before the observer in the form of allegory that at first intrigues him and then, at a later stage, helps him to reflect, to make an introspective journey within himself guided by the artist’s apparently real images. One of the main themes of Sergio Alessandrini’s production is time, a fundamental element of contemporary life of which, however, human beings tend to lose the real sense, believing it to be infinite, recoverable, relivable without realising that instead all that can be done is to grasp it and live it in the present, before it is too late, without waiting to regret what has not been grasped. This type of approach emerges clearly from the canvas The Perception of Time where the artist explores various facets, various points of view on how to deal with the most elusive element and recounts the vain attempt to capture it by discovering its secret, consisting of the lock whose key cannot be seen; at the same time, he highlights its illusion, that glass surface that infuses the sensation of an unlimitedness that is in fact immediately subverted by the frame within which it is placed, just as the two windows on either side of the composition look out onto repeated figures that seem to constitute a warning for the human being and the observer, a suggestion not to let the numbers follow one another without having used their scanning.

And again in the painting The deception Alessandrini tackles the theme of the utopia of immortality, of man’s conviction that he can be eternal, only to then come to terms with the evidence of being part of a mechanism, represented by the gears in the background, of which he is more of a victim than a protagonist, arrogantly convinced that he can manage the unmanageable, being instead just a speck within the universal forces that move the world. The artist suggests that only through culture, the one that goes beyond time and centuries, is it possible to leave a trace of oneself, to find eternity, which is only realised if one manages to break out of society’s moulds and speak with a solo voice, that of writing, which can redefine with its solemnity the feeling of false immortality in which contemporary man, with all his attention to the most superficial and vacuous things, believes he lives. Thus Sergio Alessandrini cannot fail to highlight the cages within which modernity tends to enclose the human being, inducing him to accept renunciations and limitations in the name of a conformity to society that all too often tends to standardise the individual without respecting his specificities; the artwork The Tulip and the Butterfly speaks of exactly this, of a flattening generated by the chains with which modern man often traps himself, made up of rules, dictates, unwritten laws that subtly enter life and wrap themselves around it, generating a greying, a detachment from one’s own essence that spreads to the community.

The butterfly therefore represents freedom, that rare voice out of the chorus capable of subverting the order of things by virtue of its choice to be able to rise up and detach itself from the chains by which everything is enveloped and, through its colourful lightness, it can also save those who feel the discomfort of that conformity, of that adaptation to something different from its essence. Sergio Alessandrini has experimented with various techniques to narrate his world of symbols and hidden meanings, ranging from oil on canvas to mixed media and watercolours on cotton paper, in order to retain the freedom to choose the expressive medium most akin to the emotion or meditation of the moment in which he is about to create, without ever neglecting expressive intensity, the tendency to deepen all those sensations, all those thoughts that pass through everyday life and that are often let slip by without dwelling on them. Alessandrini, on the other hand, makes them the absolute protagonists of his reflections and traverses their most hidden folds; the artist has only recently begun to exhibit his works, gaining great success with the public and interest from critics.