Il mondo femminile è stato sempre un punto di partenza affascinante per molti artisti del passato perché in qualche modo costituiva un mistero inspiegabile, un enigma da cui lasciarsi ammaliare ma che molto spesso restava irrisolto perché in fondo la mente dell’uomo non riesce a comprendere l’universo irrazionale ed emotivo della donna, limitandosi così a interpretarne quella sottile energia arcana che ne accresce la bellezza. Nella storia dell’arte moderna non solo si è assistito all’affermarsi di donne pittrici di grande talento che seppero dare un apporto diverso proprio spiegando quel mondo che conoscevano più profondamente ma si è incrementata l’interazione tra il mondo maschile e quello femminile grazie a usi e costumi e rivoluzioni della società che hanno permesso un’interazione più profonda, più empatica. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi dedica la sua produzione artistica, ma anche quella manifatturiera, alla donna con tutta la poliedricità che la contraddistingue e la rende unica.

La musa ispiratrice di quasi ogni artista dei secoli passati è stata la figura femminile, spesso avvolta dal mistero, altre invece rappresentata sotto forma di divinità da ammirare, oppure come nobildonna algida ma e distante, insomma, i grandi maestri hanno sempre avuto un debole per quell’essere etereo e incredibilmente bello di cui però non sono stati in grado di scoprire il pensiero, i segreti più intensi e profondi, limitandosi necessariamente per questo a rappresentarne lo sguardo, l’accenno di sorriso agli angoli della bocca e la loro postura di circostanza, per quanto bella e morbida fosse. Nel Novecento però, quel secolo dopo il quale niente fu più come prima anche dal punto di vista artistico, cominciarono a emergere movimenti pittorici che non si limitavano più a riprodurre la realtà esaltandone la bellezza o concentrandosi sulla perfezione esecutiva del dipinto bensì sdoganarono il campo dell’emozione, del sentire, dello spingersi oltre l’apparenza per analizzare tutto ciò che era oltre la cortina della superficie; e fu proprio in quel secolo che cominciarono ad affermarsi artiste donne di grande spessore creativo che rivoluzionarono il modo di interpretare quel mondo fino a poco prima rimasto misterioso. Frida Kahlo fu una celeberrima esponente del Surrealismo che ebbe il coraggio e la determinazione di raccontare il dolore fisico, le ferite subìte a seguito del gravissimo incidente che ne aveva segnato la vita, e di esternare in maniera esplicita un amore tormentato, intenso e travagliato che ha accompagnato tutta la sua esistenza, quello per Diego Rivera. Nelle sue opere emergeva tutto il tormento interiore che lei in qualche modo esorcizzava con l’arte e che pose il mondo femminile su un livello completamente diverso. Poi ancora Tamara De Lempicka nella sua Art Decò, pur tornando verso la bellezza algida e distante di donne borghesi e desiderose di restare nel loro mondo patinato e chic, ne rappresentò in ogni caso gli stati d’animo, la noia, la voglia di libertà, la tendenza all’indipendenza che non poteva non emergere dai loro sguardi. E ultimo esempio, ma non meno importante, Paula Rego, originaria di Lisbona ma naturalizzata inglese e una delle maggiori esponenti della Scuola di Londra, dunque sostanzialmente di matrice espressionista, le cui tele raccontano della condizione della donna nella ristretta mentalità lisbonese di qualche decennio fa e della sua ribellione, della lotta per i diritti fondamentali, delle violenze troppo spesso subite e taciute, mettendo in luce le espressioni a volte desolate altre rassegnate delle sue protagoniste. Lo sguardo delle donne nei confronti del mondo femminile aprì la strada anche ai colleghi uomini a spingersi verso un’esplorazione diversa, più profonda di quell’interiorità che aveva bisogno di essere raccontata. L’artista italo-americano-canadese Paul Albert Dari sceglie proprio l’Espressionismo per narrare un universo che conosce molto bene perché effettua un lungo percorso nel campo dell’ideazione e della realizzazione di accessori moda, costumi e borse, dunque dedicandosi completamente a studiare i gusti, le tendenze, i desideri delle donne contemporanee creando ciò che le stesse possono desiderare e acquistare per sentirsi più belle, più ammirate, più alla moda.

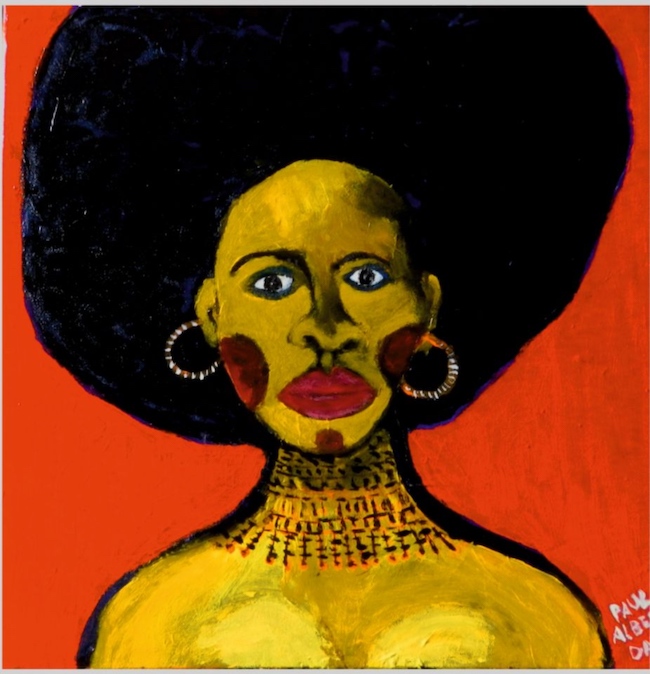

Eppure la narrazione che l’artista ne fa quando approccia la tela è molto più approfondita, non si limita a quella patina modaiola che contraddistingue il suo lato artigianale, piuttosto è interessato a dare un’impronta più intensa escludendo proprio quel velo legato alla perfezione e alla bellezza che invece contraddistingue l’ambito della moda; non è importante ciò che appare, sembra dire Paul Dari, bensì ciò che è oltre l’immagine, non serve la bellezza esteriore perché esiste una ricchezza interiore che fa passare in secondo piano un aspetto perfetto.

Questa è una delle linee guida fondamentali dell’Espressionismo che scelse di non curarsi dell’estetica per dare prevalenza alle sensazioni, al mondo emotivo, ed è esattamente ciò che contraddistingue le opere di questo artista diviso tra un istinto creativo che lo conduce verso l’approfondimento e quello artigianale che invece lo fa tendere verso l’esteriorità.

Eppure questi due aspetti in lui convivono senza contaminarsi ma al tempo stesso senza escludersi vicendevolmente, tutt’altro, forse è proprio la sua tendenza a interrogarsi sulle espressioni più incomprensibili e intime delle donne a renderlo capace di interpretarne i desideri più frivoli.

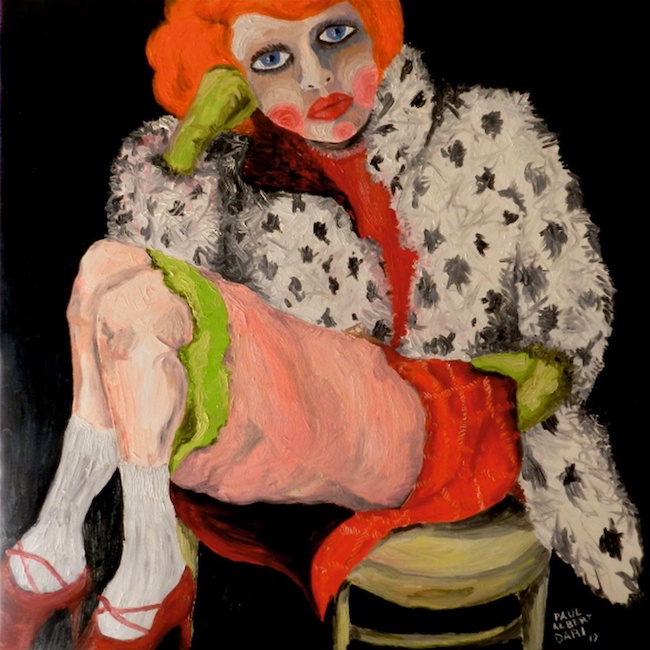

Nella tela Posa, la protagonista malgrado l’atteggiamento del corpo da cui traspare sicurezza in se stessa fino a sconfinare nella sfrontatezza, sembra avere una timidezza di fondo nello sguardo, come se tutto ciò che indossa e il modo in cui si pone fossero solo un mondo di assumere una personalità davanti al mondo che non corrisponde al suo vero io, quello che solo lei conosce. Eppure l’artista riesce a cogliere quell’impercettibile difformità tra l’apparire e l’essere, quella luce oltre gli occhi che mette in evidenza colpendo l’osservatore e attraendolo in un mondo interiore inaspettato.

Nell’opera La tanguera ciò che invece emerge è la passione della donna per la danza, quel mondo in cui ogni emozione può essere liberata senza alcun timore, in cui il movimento del corpo si allinea a quello del trasporto passionale dando vita a un tipo di libertà e di comunicatività che spesso gli individui, uomini o donne che siano, non riescono a lasciar fuoriuscire; ecco dunque che nell’espressione della figura femminile protagonista appare il senso dell’attesa per un invito, il desiderio di cimentarsi in quel vortice di sensazioni che le permette di esprimere se stessa senza filtri, lasciando che la musica guidi il corpo in perfetta armonia con quello di qualcun altro che non dovrà essere necessariamente un partner di vita bensì solo un compagno per il breve tempo dei un ballo.

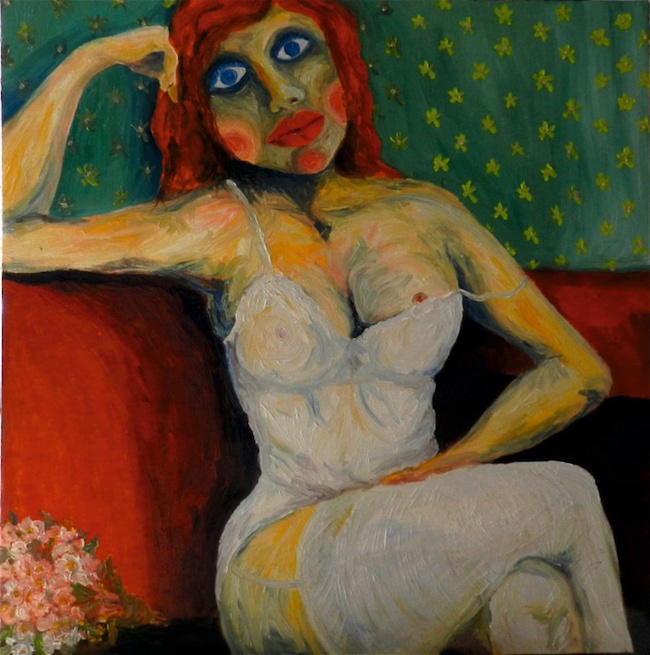

In Donna che fuma invece la sensazione che fuoriesce dalla tela è quella di rilassatezza ma anche di autocoscienza di una persona che ha preso atto dei suoi punti di forza e delle sue debolezze, che è caduta ma si è anche rialzata più volte, riuscendo a effettuare quel percorso di crescita necessario per l’evoluzione; la gamma cromatica è terrosa, quasi a esprimere la solidità faticosamente conquistata e che diviene terreno stabile su cui continuare a crescere, al di là di tutti gli accadimenti, dei cambiamenti, delle circostanze che possono verificarsi perché la consapevolezza di chi è anche in virtù del proprio passato, è incrollabile. È questo ciò che emerge dallo sguardo sicuro e determinato, al di là dei lembi di abito impalpabile che si intravedono ma che non deviano l’attenzione dai suoi occhi grandi e risoluti.

Il trucco che Paul Albert Dari mette sul volto delle donne, pur facendole somigliare a bambole di altre epoche serve in realtà a condurre l’osservatore a essere attratto dalla disarmonia per poi però lasciarsi trasportare verso altro, verso i dettagli circostanti, quelli che sono più funzionali al cammino di approfondimento che l’artista esorta a fare; è una metafora della vita la sua ma anche del rapporto uomo e donna che spesso si ferma alla superficie o al giudizio basato sulla mera apparenza. Dal punto di vista artigianale Paul Albert Dari ha creato una sua linea di borse in pezzi unici o in edizioni limitate che possono dare alla donna l’opportunità di mostrare la sua unicità anche grazie a un accessorio; dal punto di vista artistico invece ha all’attivo diverse mostre collettive sul territorio nazionale ma è ben determinato a farsi scoprire anche all’estero.

PAUL ALBERT DARI-CONTATTI

Email: paulalbertdari@gmail.com

Sito web: https://pauldari.com/

https://paulmeccanico.it/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paul.albert.dari

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/pauldari/

The multifaceted world of women in Paul Albert Dari’s Expressionism, between painting and fashion

The female world has always been a fascinating starting point for many artists of the past because in some way it constituted an inexplicable mystery, an enigma to be enchanted by but which very often remained unresolved because the human mind is unable to understand the irrational and emotional universe of women, limiting themeselves to interpreting the subtle arcane energy that enhances their beauty. In the history of modern art, we have not only witnessed the emergence of highly talented women painters who were able to make a different contribution by explaining the world they knew best, but the interaction between the male and female worlds has also increased, thanks to social customs and revolutions that have allowed a deeper, more empathetic interaction. The artist I am going to tell you about today dedicates his artistic production, but also her manufacturing one, to women with all the versatility that distinguishes her and makes her unique.

The inspirational muse of almost every artist in past centuries has been the female figure, often shrouded in mystery, others represented in the form of a divinity to be admired, or as an algid but distant noblewoman, the great masters have always had a soft spot for that ethereal and incredibly beautiful being, whose thoughts, however, they have been unable to discover, whose deepest and most intense secrets they have been unable to discover, necessarily limiting themselves to depicting their gaze, the hint of a smile at the corner of their mouth and their posture, however beautiful and soft it may have been. In the 20th century, however, the one after which nothing has no more been the same even from an artistic point of view, began to emerge pictorial movements that no longer limited themselves to reproducing reality by exalting its beauty or focusing on the perfection of the painting, but rather cleared the field of emotion, of feeling, of going beyond appearance to analyse everything that lay beyond the curtain of the surface; and it was in this century that women artists of great creative depth began to make their mark, revolutionising the way in which they interpreted their world, which until then had remained mysterious. Frida Kahlo was a celebrated exponent of Surrealism who had the courage and determination to talk about her physical pain, the wounds she suffered following the serious accident that marked her life, and to express explicitly a tormented, intense and troubled love that accompanied her entire existence, that for Diego Rivera. In her artworks all her inner torment emerged, which she somehow exorcised with art and which placed the female world on a completely different level. Then again, Tamara De Lempicka in her Art Deco, while returning to the algid and distant beauty of bourgeois women who wished to remain in their glossy and chic world, nevertheless represented their moods, boredom, desire for freedom, the tendency towards independence that could not fail to emerge from their gaze. And last but not least, Paula Rego, originally from Lisbon but now a naturalised Englishwoman and one of the leading exponents of the London School, hence essentially Expressionist, whose canvases tell of the condition of women in the narrow Lisbon mentality of a few decades ago and of their rebellion, their struggle for fundamental rights, of the violence too often suffered and concealed, highlighting the sometimes desolate and sometimes resigned expressions of her protagonists. The women’s gaze on the female world also opened the way for their male colleagues to move towards a different, deeper exploration of that interiority that needed to be told.

The Italian-American-Canadian artist Paul Albert Dari choses Expressionism to narrate a universe he knows very well because he has spent a long time designing and producing fashion accessories, costumes and bags, dedicating himself entirely to studying the tastes, trends and desires of contemporary women, creating what they might want and buy to feel more beautiful, more admired and more fashionable. And yet the artist’s narrative when he approaches the canvas is much more in-depth; he does not limit himself to the fashionable patina that distinguishes his craftsmanship, but rather he is interested in giving a more intense impression by excluding that very veil linked to perfection and beauty that instead distinguishes the field of fashion; what is important is not what it looks like, Paul Dari seems to be saying, but what is beyond the image, there is no need for external beauty because there is an inner richness that makes a perfect appearance take second place. This is one of the fundamental guidelines of Expressionism, which chose not to concern itself with aesthetics in order to give precedence to sensations, to the emotional world, and it is exactly what distinguishes the artworks of this artist divided between a creative instinct that leads him towards deepening and a craft instinct that makes him tend towards externality. And yet these two aspects coexist in him without contaminating or excluding each other; on the contrary, perhaps it is precisely his tendency to question the most incomprehensible and intimate expressions of women that enables him to interpret their most frivolous desires. In the painting Posa (Pose), the protagonist, in spite of the attitude of her body, from which she transpires self-confidence to the point of bordering on impudence, seems to have an underlying shyness in her gaze, as if everything she wears and the way she poses were just a way of assuming a personality in front of the world that does not correspond to her true self, the one that only she knows. Yet the artist succeeds in capturing that imperceptible difference between appearing and being, that light beyond the eyes that she highlights, striking the observer and drawing him into an unexpected inner world.

In the painting La tanguera (The tanguera), however, what emerges is the woman’s passion for dance, that world in which every emotion can be released without fear, in which the movement of the body is aligned with that of the passionate impulse, giving rise to a type of freedom and communicativeness that individuals, whether men or women, often fail to allow to emerge; in the expression of the female protagonist, therefore, the sense of waiting for an invitation appears, the desire to engage in that vortex of sensations that allows her to express herself without filters, letting the music guide her body in perfect harmony with that of someone else, who need not necessarily be a life partner but only a companion for the brief time of a dance. In Donna che fuma (Woman Who Smokes), on the other hand, the sensation that emerges from the canvas is one of relaxation but also of the self-awareness of a person who has taken note of her strengths and weaknesses, who has fallen but has also got back up several times, managing to carry out that path of growth necessary for evolution; the chromatic range is earthy, almost as if to express the solidity that has been painstakingly achieved and that becomes stable ground on which to continue growing, beyond all the events, changes and circumstances that may occur because the awareness of who one is, also by virtue of one’s past, is unshakeable. This is what emerges from his confident and determined gaze, beyond the flaps of impalpable clothing that can be glimpsed but which do not divert attention from his large, resolute eyes. The make-up that Paul Albert Dari puts on the women’s faces, even though it makes them look like dolls from other eras, actually serves to lead the observer to be attracted by disharmony, but then to let himself be transported towards something else, towards the surrounding details, those that are more functional to the path of in-depth study that the artist urges us to take; his is a metaphor of life but also of the relationship between man and woman that often stops at the surface or at judgement based on mere appearance. From the point of view of craftsmanship, Paul Albert Dari has created his own line of handbags in unique pieces or limited editions that give women the opportunity to show off their uniqueness through an accessory; from the artistic point of view, however, he has a number of group exhibitions to his credit in Italy, but is determined to be discovered abroad as well.