La necessità di raccontare tutto ciò che lo sguardo, a volte distrattamente, coglie nel vissuto quotidiano emerge in molti artisti contemporanei, alcuni dei quali si concentrano solo e unicamente sul sentire escludendo l’immagine, altri invece rimangono fortemente legati alla figurazione, a quel contatto con l’osservato necessario a mettere in evidenza quegli istanti irripetibili da cui lasciarsi conquistare e ammaliare proprio per la caratteristica di fugacità che li contraddistingue. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi appartiene al secondo gruppo di creativi e, con il suo particolare linguaggio pittorico è in grado di lasciare all’osservatore la sensazione di trovarsi davanti a un caleidoscopio di fotogrammi che induco a credere che un secondo dopo tutto l’insieme della composizione potrebbe cambiare e trasformarsi in altro.

Intorno alla fine del Diciannovesimo secolo cominciarono a delinearsi le prime avanguardie che avvertivano il bisogno di introdurre un modo diverso di intendere l’espressione artistica, secondo un approccio nuovo che andava in contrasto con le linee guida accademiche precedenti e che proprio a causa di questo apporto innovativo furono osteggiate, almeno in principio. Tuttavia il cambiamento della società, le profonde modificazioni e l’esigenza sempre più forte di adeguare il mondo creativo e culturale a una maggiore velocità, a un impensabile rapido progresso, e a un pubblico più ampio rispetto alla ristretta cerchia della nobiltà, costrinsero anche i personaggi di rilievo del circuito dell’arte ad arrendersi ai cambiamenti e lasciare che il nuovo sostituisse o quanto meno coesistesse con tutto ciò che c’era stato in precedenza. L’Espressionismo fu una di quelle correnti che con più forza vollero sottolineare il diritto delle emozioni di prendere il sopravvento sulla realtà circostante, perché l’arte, che non doveva più essere un mero mezzo di riproduzione delle immagini, in quanto per questo si stava ormai affermando la fotografia, doveva legarsi al sentire, a quelle sensazioni in grado di travolgere l’interiorità tanto quanto l’opera d’arte dovesse divenire mezzo per esprimere quelle profondità. Dunque il distacco dalla terza dimensione e dal chiaroscuro, l’introduzione di tonalità cromatiche intense e irreali, l’abbandono di quell’equilibrio estetico e formale che aveva contraddistinto i pittori dei secoli precedenti, la mancanza di un qualsiasi schema compositivo e di profondità, tutto era funzionale a sottolineare l’importanza del punto di vista soggettivo dell’esecutore dell’opera. La contrapposizione con il Realismo che, al contrario, aveva dominato i decenni centrali dell’Ottocento era evidente e stridente eppure, con l’avvicinarsi del Ventesimo secolo e l’apertura dei creativi al confronto e all’accettazione delle diversità stilistiche, tanto quanto alla modificazione di tutto ciò che prima esisteva in un modo diverso, consentirono al Realismo di sopravvivere, al tratto perfetto, alla terza dimensione e alla gamma cromatica attinente alla realtà di divenire la base di successivi movimenti che trasgredirono e oltrepassarono la fedeltà a ciò che l’occhio poteva osservare trasportando il fruitore in mondi paralleli, come nel caso del Surrealismo, oppure misteriosi come nella Metafisica. Nei primi decenni del Ventesimo secolo anche l’Espressionismo attenuò il suo aspetto stilistico, quello per intenderci più vicino all’irruenza cromatica dei Fauves, senza però mai perdere il suo principale scopo, e cioè rimanere fortemente legato alla sfera interiore. È proprio in questo contesto che può essere collocata la cifra pittorica dell’artista austriaco Walter Schubert, in una terra di mezzo tra l’intensità comunicativa dell’Espressionismo e la necessità di aderire al visibile tipica del Realismo, senza che però l’uno prevalga sull’altro, come se fosse proprio nella strada di mezzo che egli riesce a trovare il linguaggio perfetto attraverso cui sospende le sue opere in un frammento di realtà avvolto da tutta quella miriade di piccole sensazioni che riescono a fuoriuscire proprio grazie allo sguardo rivelatore dell’artista.

Persino la scelta cromatica mostra la sua attitudine a rimanere in bilico tra realtà e percezione interiore, tra il raccontare e il lasciare intuire o immaginare, tra l’essere e l’intravedere, esattamente come se usasse una telecamera con cui riprende i frammenti di immagine in modo accelerato per poi rilasciare un fotogramma di un fuggevole istante; in virtù di questa evanescenza del momento immortalato, Walter Schubert descrive nitidamente alcuni dettagli, quelli su cui desidera si focalizzi l’attenzione dell’osservatore, mentre lascia più indefinite le parti trascurabili, gli sfondi, a meno che non siano fondamentali per l’ambientazione, allora anche un elemento di contorno può diventare parte integrante e funzionale del frangente che ha catturato la sua sensibilità artistica.

Proprio per questa sua caratteristica di usare la figurazione sulla base dell’esigenza comunicativa, in alcune opere tende verso la Metafisica perché i suoi personaggi sono decontestualizzati, impalpabili, sospesi tra realtà e possibilismo, come se in fondo ciò che è divenisse più concreto esattamente grazie a ciò che potrebbe essere; la collocazione dei protagonisti è infatti immaginaria, appartengono a qualunque luogo, si trovano in un posto indefinito che potrebbe essere in ogni parte del mondo, perché in fondo ciò che conta è il frangente descritto, la loro sensazione che può emergere da uno sguardo, da un sorriso, da un gesto spontaneo o da una non presenza.

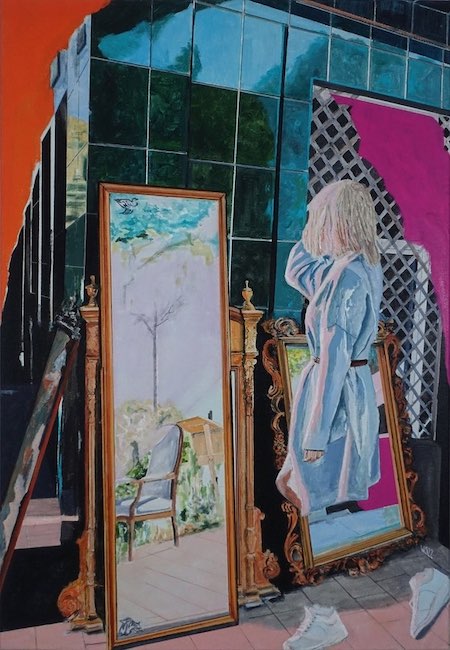

Quest’ultimo concetto è perfettamente descritto nell’opera Daily Mirror in cui la ragazza è davanti a uno specchio che non rimanda la sua immagine bensì racconta di un’altra ambientazione, forse un sogno o un ricordo verso cui la sua memoria inevitabilmente corre; e in effetti una parte di sé non è presente, le sue gambe sembrano non esserci proprio per sottolineare il suo desiderio di trovarsi lontana, all’interno di quel mondo che le rimanda una situazione felice e serena che ha vissuto. Il fatto che il titolo accenni a una quotidianità sottolinea quanto l’uomo contemporaneo sia spesso costretto a restare distante dal proprio sogno, dal luogo a cui sente di appartenere, per lasciar prevalere il pragmatismo, l’esigenza contingente di non poter sempre scegliere ciò che davvero vorrebbe.

Nell’opera Magenta meets Violet invece traspare la sensazione contraria, quella della donna sicura di sé e di ciò che ha voluto essere, ed è questo il frammento che Walter Schubert coglie, quell’istante in cui, sapendo di essere osservata, non può fare a meno di mostrare la sua determinazione, la sua forza, quasi stesse sfidando quell’osservatore indiscreto che sta in qualche modo entrando nel suo spazio vitale e nella sua anima. La ragazza ha con sé una chitarra elettrica, simbolo di libertà perché avere il coraggio di intraprendere una carriera musicale richiede abnegazione, attitudine all’indipendenza e capacità di rompere gli schemi dentro cui molti si rifugiano; e dunque i colori dello sfondo si armonizzano con le sue caratteristiche, il violetto da sempre associato all’anima e dunque alla capacità di restare in contatto con essa, e il blu elettrico simbolo di fiducia nelle proprie capacità.

Ma l’attitudine più prismatica di Walter Schubert si svela nelle opere della serie Everglow, ispirate alla canzone dei Cold Play che porta lo stesso titolo, che di fatto sono dei fotogrammi in sequenza delle emozioni e delle sensazioni evocate dal testo e narrate con la capacità dell’artista di andare a cogliere esattamente quel momento irripetibile che potrebbe svanire un istante dopo essere stato immortalato. Di fatto le tele di questa serie sono un omaggio alle donne, con la loro unicità, con la loro sensibilità, con la capacità di illuminare un giorno solo con un sorriso, resa evidente da Schubert immortalando quei volti in scala di grigi, come se tutto ciò che avesse bisogno di essere messo in risalto fosse solo e unicamente l’intensità delle emozioni provate.

Gli sfondi sono invece pure macchie di colore in accordo alla personalità delle ragazze protagoniste e del frammento di sensazione che deve emergere, dunque arancio per sottolineare la vitalità e l’allegria, il celeste per mettere in risalto un atteggiamento più intimista e riflessivo, il giallo per una personalità più determinata e al tempo stesso diffidente.

Walter Schubert, formatosi inizialmente come autodidatta, ha frequentato per molti anni diversi corsi presso l’Accademia di Pittura Geras che gli hanno permesso di perfezionare la sua tecnica frutto di un’inclinazione naturale verso la figurazione; partecipa a molte mostre collettive in Bassa Austria, dove vive, e anche a Vienna, riscuotendo grande successo di pubblico e di critica.

WALTER SCHUBERT-CONTATTI

Email: waschubert@gmail.com

Sito web: www.wschubert.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/wschubert.art

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/wschubert.art/

Fragments of existence in the artworks poised between Expressionism and Realism by Walter Schubert

The need to recount everything that the gaze, sometimes distractedly, catches in everyday life emerges in many contemporary artists, some of whom concentrate solely and exclusively on feeling to the exclusion of the image, while others remain strongly attached to figuration, to that contact with the observed that is necessary to highlight those unrepeatable instants from which to be conquered and bewitched precisely because of the characteristic fleetingness that distinguishes them. The artist I am going to tell you about today belongs to the second group of creatives and, with his particular pictorial language, is able to leave the observer with the sensation of being in front of a kaleidoscope of photograms that lead one to believe that one second later the whole composition could change and turn into something else.

Around the end of the 19th century, began to emerge the first avant-gardes began that felt the need to introduce a different way of intending the artistic expression, according to a new approach that went against the previous academic guidelines and that precisely because of this innovative contribution were opposed, at least in the beginning. However, the change in society, the profound modifications and the ever-increasing need to adapt the creative and cultural world to greater speed, to an unthinkably rapid progress, and to a broader public than the narrow circle of the nobility, forced even the leading figures in the art circuit to surrender to the changes and let the new replace or at least coexist with everything that had gone before. Expressionism was one of those currents that most forcefully wanted to emphasise the right of the emotions to take over from the surrounding reality, because art, which was no longer to be a mere means of reproducing images, as photography was now becoming established for this, had to bind itself to feeling, to those sensations capable of overwhelming the interiority as much as the work of art had to become a means of expressing those depths. Thus, the detachment from the third dimension and chiaroscuro, the introduction of intense and unreal colour tones, the abandonment of that aesthetic and formal balance that had distinguished the painters of previous centuries, the lack of any scheme of composition and depth, all served to emphasise the importance of the subjective point of view of the artwork’s executor. The contrast with Realism which, on the contrary, had dominated the central decades of the 19th century, was clear and strident, yet as the 20th century approached and creatives were open to confrontation and acceptance of stylistic diversity, as much as to modifying everything that had previously existed in a different way, allowed Realism to survive, the perfect stroke, the third dimension and the colour range pertaining to reality to become the basis for subsequent movements that transgressed and went beyond fidelity to what the eye could observe, transporting the viewer into parallel worlds, as in the case of Surrealism, or mysterious ones as in Metaphysics.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Expressionism also toned down its stylistic aspect, the one closer to the chromatic impetuosity of the Fauves, but without ever losing its main purpose, which was to remain strongly linked to the inner sphere. It is precisely in this context that the pictorial style of the Austrian artist Walter Schubert can be placed, in a middle ground between the communicative intensity of Expressionism and the need to adhere to the visible typical of Realism, without one prevailing over the other, as if it was precisely in the middle ground that he managed to find the perfect language through which he suspended his artworks in a fragment of reality enveloped in all the myriad of small sensations that manage to escape thanks to the artist’s revelatory gaze. Even his choice of colour shows his aptitude for hovering between reality and inner perception, between telling and letting guess or imagine, between being and glimpsing, exactly as if he were using a camera with which he shoots fragments of images in an accelerated manner and then releases a frame of a fleeting instant; by virtue of this evanescence of the immortalised moment, Walter Schubert sharply describes certain details, those on which he wants the observer’s attention to focus, while he leaves the negligible parts, the backgrounds, more indefinite, unless they are fundamental to the setting, then even an outline element can become an integral and functional part of the juncture that has captured his artistic sensibility. Precisely because of this characteristic of using figuration on the basis of communicative need, in some paintings he tends towards the Metaphysical because his characters are decontextualised, impalpable, suspended between reality and possibilism, as if in the end what is became more concrete precisely because of what could be; the location of the protagonists is in fact imaginary, they belong to any place, they are in an undefined place that could be anywhere in the world, because in the end what counts is the juncture described, their feeling that can emerge from a glance, a smile, a spontaneous gesture or a non-presence. This last concept is perfectly described in the canvas Daily Mirror in which the girl is in front of a mirror that does not reflect her image but tells of another setting, perhaps a dream or a memory towards which her memory inevitably runs; and in fact a part of herself is not present, her legs seem not to be there precisely to emphasise her desire to be far away, within that world that refers her to a happy and serene situation she has experienced. The fact that the title hints at an everyday life underlines how contemporary man is often forced to remain far away from his own dream, from the place where he feels he belongs, in order to let pragmatism prevail, the contingent need of not always being able to choose what he really wants.

In the painting Magenta Meets Violet, on the other hand, transpires the opposite feeling, that of the woman who is sure of herself and of what she wanted to be, and this is the fragment that Walter Schubert captures, that instant in which, knowing she is being observed, she cannot help but show her determination, her strength, almost as if she were challenging that indiscreet observer who is somehow entering her living space and her soul. The girl is carrying an electric guitar, a symbol of freedom because having the courage to embark on a musical career requires self-denial, an aptitude for independence and the ability to break the mould within which many take refuge; and so the colours in the background harmonise with her characteristics, violet, which has always been associated with the soul and thus with the ability to stay in touch with it, and electric blue, a symbol of confidence in one’s own abilities. But Walter Schubert‘s more prismatic attitude is revealed in the artworks of the Everglow series, inspired by the Cold Play song that has the same title, which are in fact photograms in sequence of the emotions and sensations evoked by the lyrics and narrated with the artist’s ability to capture exactly that unrepeatable moment that could vanish an instant after being immortalised. In fact, the canvases in this series are a tribute to women, with their uniqueness, their sensitivity, their ability to brighten up a day with just a smile, made evident by Schubert by immortalising those faces in greyscale, as if all that needed to be emphasised was the intensity of the emotions felt. The backgrounds, on the other hand, are pure patches of colour in accordance with the personality of the girls protagonists and the fragment of sensation that has to emerge, so orange to emphasise vitality and cheerfulness, light blue to emphasise a more intimate and reflective attitude, yellow for a more determined and at the same time diffident personality. Walter Schubert, who initially trained as a self-taught artist, attended various courses at the Geras Painting Academy for many years, which enabled him to improve his technique, the result of a natural inclination towards figuration. He has taken part in many group exhibitions in Lower Austria, where he lives, and also in Vienna, gaining great success with the public and critics.