L’approccio attuale all’arte, malgrado presenti dal punto di vista esteriore espressività riconducibili alle esplorazioni e sperimentazioni effettuate nel secolo scorso, ha di fatto un tipo di consapevolezza differente, più ampia, decisamente orientata a introdurre nel gesto plastico anche una riflessione sul significato profondo, dunque non solo emozionale bensì anche mentale, che entra all’interno dell’opera stessa costituendone una parte essenziale. Questo avviene maggiormente quando si tende verso l’indefinitezza, la non immagine che assume sfumature differenti a seconda dell’indole e del sentire del soggetto osservante, per far sì che essa diventi non solo pura percezione bensì anche meditazione sul concetto contemporaneo di interattività, di elevazione dell’arte a qualcosa di differente dalla pura contemplazione. Il protagonista di oggi non solo è interprete di questo approccio creativo ma elabora un concetto filosofico con cui arricchisce le sue opere.

Il mondo artistico moderno sembrava essere insofferente verso tutti gli schemi e le regole accademiche tradizionali poiché in contrasto con l’evolversi dei tempi e con la velocità evolutiva dei primi decenni del Novecento, pertanto emersero in questo vivace periodo movimenti che volevano sdoganare alcuni limiti che ormai non avevano più ragione di esistere. Già verso la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo in Inghilterra, l’Arts and crafts aveva mostrato al mondo quanto l’interazione con l’artigianato, tradizionalmente escluso dalla considerazione che ricevevano le belle arti come la pittura e la scultura, potesse invece dar vita a oggetti unici di grande valore, oltre che ampliare le conoscenze e le applicazioni delle tecniche principali, combattendo così l’incalzante industrializzazione che tendeva a oltrepassare il lavoro manuale abbassando notevolmente i prezzi degli oggetti e lasciando pertanto poco spazio all’antico artigiano. La successiva Arte Nuova ampliò ancor più il campo di applicazione dell’arte e di contaminazione con oggettistica, gioielleria, decoro urbano e nell’architettura; fu poi però la Bauhaus a creare un vero e proprio studio su questo nuovo approccio creativo e, sebbene con manifestazione stilistica completamente differente dall’Art Nouveau, di fatto accolse quel fondamentale suggerimento di apertura nei confronti delle varie discipline figurative. Nella scuola ideata e fondata da Walter Gropius infatti, gli allievi potevano approfondire, il design, l’architettura, la pittura, la scultura, la decorazione del vetro, la tipografia, la grafica, il teatro, la tessitoria, la falegnameria, tutto sotto quel Razionalismo che apparteneva all’impronta stilistica dell’istituto. Questa esperienza fu ripresa essenzialmente da molte correnti che seguirono, persino quando la forma espressa era completamente difforme, e costituì la base di tutta l’Arte Concettuale e dell’Informale Materico che contraddistinsero la seconda metà del Novecento. Alberto Burri con la sua intensa emozione, Antoni Tàpies con il suo desiderio di rendere protagonista la materia di oggetti ormai non più utilizzati e infine tutta l’Arte Cinetica, le contemporanee installazioni hanno proseguito quel cammino ampliando ed espandendo il dialogo tra arte, materia, musica, meccanica e interazione con il fruitore. L’artista e architetto marchigiano Claudio Pantana abbraccia le linee guida della grande scuola di inizio Novecento riadattandola al suo linguaggio artistico, quello di un Informale Materico che si pone come obiettivo il dare continua vita a oggetti che diversamente finirebbero per essere accantonati e gettati via, e al tempo stesso rigenerarli come in un ciclo continuo per farli rientrare in altri spazi, prendendo la loro inutilità per trasformarla in qualcosa di emozionalmente appagante ed esteticamente funzionale.

Sì perché la sua filosofia è quella dell’Estetica dell’uso che consiste in una progettualità che lo spinge a mettere in relazione il suo lato artistico, quello che ha bisogno della non forma per lasciar fluire le proprie sensazioni sulla tela, e il suo approccio di architetto, dunque più mentale, più schematico e predisposto alla praticità dell’oggetto, persino quando si tratta di un pezzo d’arte perché in fondo arredare significa anche rendere bello e accogliente l’ambiente in cui si vive. Non solo, tutto ciò che viene presto considerato inutile, secondo il contemporaneo approccio del mordi e fuggi che induce l’individuo a perdere interesse in qualcosa paradossalmente subito dopo averlo ottenuto, può trovare un nuovo impiego, una nuova vita che trascende il motivo per cui esso è stato creato e interagisce con l’uomo e con l’ambiente intorno a sé in maniera completamente diversa, coinvolgente perché parte di un qualcosa che non potrà mai più diventare desueto proprio perché il linguaggio artistico è senza tempo.

Si potrebbe associare il concetto espressivo di Claudio Pantana alle teorie delle filosofie orientali della sopravvivenza e della reincarnazione, secondo cui la vita precedente è inferiore a quella successiva in un corso e ricorso evolutivo sostanzialmente eterno; e questo concetto emerge anche nelle opere dedicate ai quattro elementi, acqua-aria-terra-fuoco in cui, come davanti a una costante rigenerazione, ne esplora differenti combinazioni, leggere varianti che ne modificano l’aspetto ma non l’essenza.

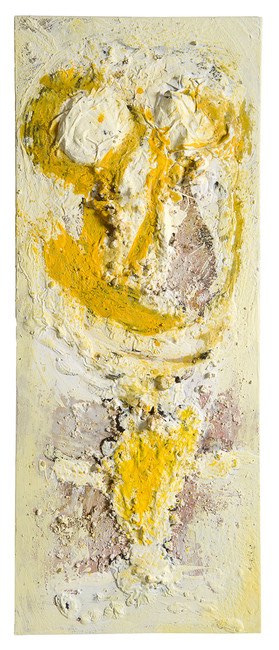

Ecco dunque che in Fuoco aria, la materia costituita da legno, carta e materiali vari va a rappresentare fiamme centrali che sembrano alimentarsi in verticale proprio per la leggerezza dell’aria che le spinge verso l’alto, in qualche modo forse controllandole; il fatto che esse non si propaghino in larghezza costituisce quasi una rassicurazione esprimendo la metafora che l’evanescenza e l’impalpabilità possano contrastare l’irruenza, l’impeto che tende a prevaricare e a invadere.

Diversamente, in Fuoco acqua la fiamma, il rosso intenso, si propaga in orizzontale e in maniera confusa, come se volesse disperatamente contrastare la forza pacata del suo elemento opposto, l’acqua, in grado con la sola presenza di spegnere ogni incendio. Anche in questo caso la similitudine con il comportamento umano è quasi inevitabile poiché molto spesso tutto ciò che sembra essere sopra le righe, irruento e prepotente, qualità attribuibili al fuoco, viene placato da un atteggiamento opposto, apparentemente tranquillo e invece forse persino più forte, perché in grado di controllarsi, agire silenziosamente per andare a mitigare gli eccessi.

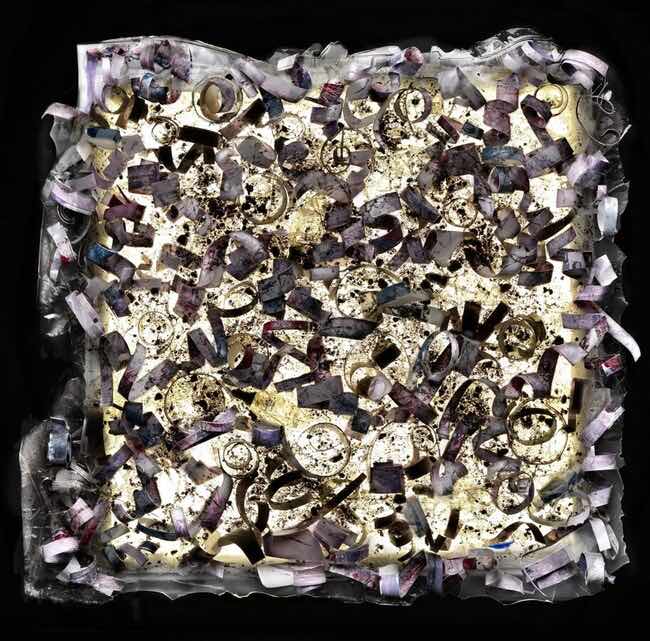

Il forte legame di Claudio Pantana con il design e l’arredamento d’interni emerge però nelle Creazioni di luce, opere d’arte concepite per divenire un dettaglio unico che può anche diventare il punto focale di un appartamento, unendo la funzionalità all’estetica, infatti questa serie di lavori sono illuminati da luce al led in virtù della quale tutti i dettagli sono amplificati, complice anche la presenza del plexiglas che con il suo aspetto trasparente rifrange la luce contenendo tutti gli elementi materici che di volta in volta vanno a strutturare la composizione.

Ogni creazione è un pezzo unico, originale, elemento d’arredo che si basa su un binomio estetico, quello della contemplazione concettuale che suscita la riflessione su quanto ciascun dettaglio dell’opera sia un pezzo recuperato e rinato a nuova vita, e quello del coinvolgimento puramente estetico del fascino della luce che permette all’indefinitezza dell’immagine finale di fuoriuscire dal supporto assumendo una struttura tridimensionale accentuata proprio dalla presenza dei led.

Per Claudio Pantana non esiste oggetto che non possa trasformarsi in bellezza e in arte, persino una semplice sedia può diventare uno spunto creativo ed è esattamente su questo approccio filosofico che ha creato le sedute Amore e Psiche, vicine eppure differenti nella gamma cromatica necessaria all’artista per distinguere le essenze dei due amanti, opposti nella sostanza ma che solo insieme riescono a completarsi. Ed è proprio sulla base del mito greco che vengono realizzate le due sedie, ottenute assemblando tavole di legno trovate in un cantiere edile e rigenerate con un trattamento a colore variopinto e vivace che le rende un pezzo di design contemporaneo. La sua Estetica dell’uso si materializza così in tutta la sua manifestazione creativa unendo l’attuale Arte del Riciclo al concetto di praticità, trasformando la bellezza plastica in oggetto di cui poter fruire quotidianamente. Ma il suo sogno è quello di ampliare questa sua filosofia facendola diventare un punto di dialogo tra varie forme artistiche, dal teatro alla musica, dal design alla moda alla poesia, oltre ovviamente all’arte e alla scultura, tanto quanto era stato fatto un secolo fa proprio dalla Bauhaus. Claudio Pantana ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre in Italia e all’estero – Osaka, Bangkok, New York, Dubai – sia nel campo dell’arte che in quello del design ed è membro dell’Associazione Culturale Don Quijote di Fermo.

CLAUDIO PANTANA-CONTATTI

Email: claudio_pantana@yahoo.it

Sito web: www.architettopantana.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/claudio.pantana.3

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/claudiopantanaartdesign/

The philosophy of interactivity and reuse in Claudio Pantana’s Material Informal

The current approach to art, despite presenting from the external point of view expressions traceable to the explorations and experimentations carried out in the last century, has in fact a different type of awareness, broader, definitely oriented to introduce in the plastic gesture also a reflection on the deep meaning, therefore not only emotional but also mental, that enters inside the artwork itself constituting an essential part of it. This happens more when tending toward indefiniteness, the non-image that takes on different nuances depending on the temperament and feeling of the observing subject, so that it becomes not only pure perception but also meditation on the contemporary concept of interactivity, of elevating art to something different from pure contemplation. Today’s protagonist is not only an interpreter of this creative approach but also elaborates a philosophical concept with which he enriches his artworks.

The modern art world seemed to be intolerant of all traditional patterns and academic rules since they were at odds with the changing times and the evolutionary speed of the first decades of the twentieth century, so movements emerged in this lively period that wanted to clear certain limits that by then had no reason to exist. Already towards the end of the nineteenth century in England, Arts and crafts had shown the world how interaction with craftsmanship, traditionally excluded from the consideration received by fine arts such as painting and sculpture, could instead give rise to unique objects of great value, as well as expand the knowledge and applications of the main techniques, thus combating the pressing industrialization that tended to overstep manual labor by greatly lowering the prices of objects and thus leaving little room for the old craftsman. The later Art Nouveau broadened even more the scope of art’s application and contamination with objects, jewelry, urban decoration and in architecture; it was then, however, the Bauhaus that created a real study of this new creative approach and, although with stylistic manifestation completely different from Art Nouveau, in fact embraced that fundamental suggestion of openness to the various figurative disciplines. In the school conceived and founded by Walter Gropius in fact, students could delve into, design, architecture, painting, sculpture, glass decoration, typography, graphics, theater, weaving, carpentry, all under that Rationalism that belonged to the stylistic imprint of the institute. This experience was taken up essentially by many currents that followed, even when the form expressed was completely dissimilar, and formed the basis of all Conceptual Art and Material Informal that distinguished the second half of the twentieth century.

Alberto Burri with his intense emotion, Antoni Tàpies with his desire to make the material of objects no longer used as protagonists, and finally all of Kinetic Art, contemporary installations have continued that path by broadening and expanding the dialogue between art, matter, music, mechanics and interaction with the user. Marche-based artist and architect Claudio Pantana embraces the guidelines of the great school of the early twentieth century by readapting it to his artistic language, that of a Materic Informal that aims at giving continuous life to objects that would otherwise end up being shelved and thrown away, and at the same time regenerating them as in a continuous cycle to make them re-enter other spaces, taking their uselessness and transforming it into something emotionally satisfying and aesthetically functional. Yes, because his philosophy is that of the Aesthetics of Use, which consists of a design that pushes him to relate his artistic side, the one that needs the non-form to let its sensations flow on the canvas, and his approach as an architect, therefore more mental, more schematic and predisposed to the practicality of the object, even when it is a piece of art because after all, furnishing also means making the environment in which one lives beautiful and welcoming. Not only that, everything that is soon considered useless, according to the contemporary hit-and-run approach that induces the individual to lose interest in something paradoxically soon after getting it, can find a new use, a new life that transcends the reason for which it was created and interacts with man and the environment around him in a completely different way, engaging because it is part of something that can never again become obsolete precisely because artistic language is timeless. One could associate Claudio Pantana‘s expressive concept with the theories of Eastern philosophies of survival and reincarnation, according to which the previous life is inferior to the next one in an essentially eternal evolutionary course and recourse; and this concept also emerges in the artworks dedicated to the four elements, water-air-earth-fire in which, as if in front of a constant regeneration, he explores different combinations of them, slight variations that change their appearance but not their essence. Here, then, in Fuoco aria, the material consisting of wood, paper and various materials goes to represent central flames that seem to feed vertically precisely because of the lightness of the air that pushes them upward, in some way perhaps controlling them; the fact that they do not spread in width almost constitutes a reassurance by expressing the metaphor that evanescence and impalpability can counteract the vehemence, the impetuosity that tends to prevail and invade. In contrast, in Fire Water the flame, the intense red, spreads horizontally and in a confused manner, as if desperate to counteract the calm force of its opposite element, water, capable by its mere presence of extinguishing any fire. Again, the similarity with human behavior is almost inevitable since very often everything that seems to be over the top, impetuous and overbearing, qualities attributable to fire, is quelled by an opposite attitude, seemingly calm and instead perhaps even stronger, because it is able to control itself, to act silently to go and mitigate the excesses.

Claudio Pantana‘s strong link with design and interior design emerges, however, in Creations of Light, works of art conceived to become a unique piece that can also become the focal point of an apartment, combining functionality with aesthetics, in fact, this series of works are illuminated by LED light by virtue of which all the details are amplified, also accomplice the presence of Plexiglas that with its transparent appearance refracts light containing all the materic elements that from time to time go to structure the composition. Each creation is a unique, original piece, a furnishing element that is based on an aesthetic pair, that of conceptual contemplation that provokes reflection on how much each detail of the artwork is a piece recovered and reborn to new life, and that of the purely aesthetic involvement of the fascination of light that allows the indefiniteness of the final image to escape from the support assuming a three-dimensional structure accentuated precisely by the presence of LEDs. For Claudio Pantana, there is no object that cannot be transformed into beauty and art, even a simple chair can become a creative cue and it is exactly on this philosophical approach that he created the Amore and Psiche seats, close yet different in the chromatic range necessary for the artist to distinguish the essences of the two lovers, opposites in substance but only together able to complete each other. And it is precisely on the basis of the Greek myth that the two chairs are made, obtained by assembling wooden planks found in a construction site and regenerated with a colourful and lively colour treatment that makes them a piece of contemporary design.. His Aesthetics of Use is thus materialized in all its creative manifestation by combining the current Art of Recycling with the concept of practicality, transforming plastic beauty into an object that can be enjoyed on a daily basis. But his dream is to expand this philosophy by making it a point of dialogue between various artistic forms, from theater to music, from design to fashion to poetry, as well as, of course, art and sculpture, much as was done a century ago by the Bauhaus itself. Claudio Pantana has to his credit participation in exhibitions in Italy and abroad – Osaka, Bangkok, New York, Dubai – both in the fields of art and design and is a member of the Don Quijote Cultural Association of Fermo.