L’era contemporanea è contraddistinta da una semplicità e immediatezza nel riprodurre frammenti di istanti vissuti che tendono spesso a far passare in secondo piano l’importanza del frangente per dare la priorità all’apparenza, all’immagine, più che alla sostanza. Eppure vi sono artisti, perché solo in questo modo possono essere definiti coloro i quali approcciano la fotografia in mondo intenso, poetico e romantico, che preferiscono soffermarsi sul dettaglio, sulla lentezza e sull’intensità del vissuto piuttosto che sulla fretta e l’urgenza di apparire. La protagonista di oggi utilizza la macchina fotografica quasi come fosse un pennello, trasformando un particolare, un dettaglio ordinario in qualcosa di straordinario.

Con il progredire delle scoperte tecnologiche e gli studi sulla riproduzione delle immagini che subì una forte accelerazione in quel dinamico e vivace Ventesimo secolo che, soprattutto nella prima parte, portò notevoli cambiamenti nel mondo artistico e culturale, cominciò a diffondersi la fotografia, non più destinata solo a esperti in grado di trasportare gli ingombranti e pesanti apparecchi in uso nel secolo precedente, bensì vennero create macchine più leggere e maneggevoli rendendo la possibilità di avere un ritratto fotografico più accessibile a un maggior numero di persone e rispetto a quello pittorico, ma anche concedendo a reporter e giornalisti di documentare frangenti importanti della storia dell’epoca. In qualche modo dunque, nei primi decenni del Novecento si creò quasi una contrapposizione tra arte e fotografia, perché un considerevole numero di artisti si mise in una posizione di difesa e volle distaccarsi dalla nuova tecnologia dando vita all’Astrattismo che affermava la priorità e la supremazia del gesto plastico rispetto alla freddezza di uno scatto fotografico. Eppure nel corso di quegli anni anticonformisti e sovvertivi le due tendenze non potevano non entrare in contatto e influenzarsi vicendevolmente, in particolar modo in una delle correnti artistiche più fuori dagli schemi, il Surrealismo, che con la sua tendenza a sperimentare accolse al suo interno due grandi fotografi, Man Ray e Bill Brandt, capaci di far emergere l’inconscio sia assecondando il loro intuito espressivo sia dalla realtà osservata di cui mostravano i lati oscuri allo sguardo comune. Da quel momento in avanti la fotografia cominciò a essere considerata per ciò che era, e cioè arte, diversa da quella più manuale della pittura o della scultura, ma comunque una forma espressiva intensa e coinvolgente che continuò a essere influenzata dalle correnti pittoriche prendendone spunto; la metà del secolo Diciannovesimo generò la più numerosa e importante generazione di fotografi di ogni tempo, dai cui scatti non poteva non scaturire emozione, coinvolgimento che arrivavano diretti all’osservatore avvolgendolo con le loro atmosfere. Il romanticismo di Robert Doisneau, l’ironia di Elliot Erwitt, l’indagine sociale di Gianni Berengo Gardin, solo per citarne alcuni maestri del bianco e nero, si affiancavano alle forti quanto immortali e apparentemente immobili immagini di reportage di Steve McCurry e a quelle paesaggistico-metafisiche di Franco Fontana, entrambi massimi esponenti della fotografia a colori; tutti a loro modo hanno sottolineato la versatilità della tecnica fotografica e la possibilità di fare arte con le loro macchine che oggi sono considerate superate.

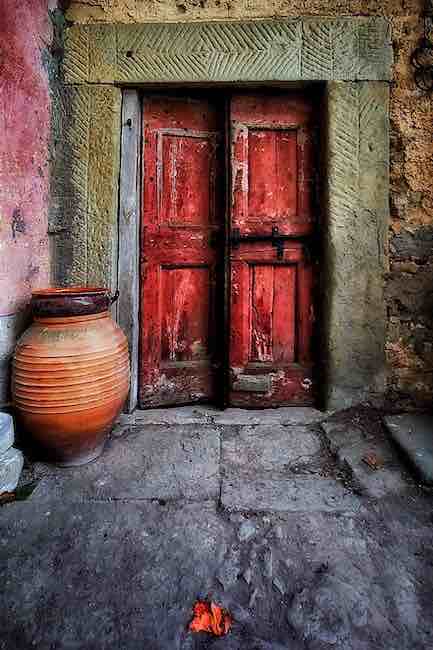

L’artista bolognese Maria Grazia Ferri sposa a sua volta il mondo del colore, come se il suo concetto di fotografia sentisse il bisogno di avvalersi di una gamma cromatica che usa per evidenziare i dettagli per lei essenziali, quelli che devono essere protagonisti dei suoi scatti, a cui riesce a dare una connotazione quasi fiabesca, vicina alle atmosfere filmografiche di Tim Burton, in cui il tempo è sospeso, dove non sembra esservi né lo ieri né il domani, semplicemente il presente immobile messo in evidenza dallo sguardo romantico della fotografa.

Gli oggetti, i dettagli, sono messi in risalto da una scelta di tonalità sature, piene, quasi espressioniste in quel loro legarsi all’emozione, alla sensazione che la Ferri avverte nell’osservare le scene e che sente il desiderio di immortalare; sembra quasi che ogni particolare sia accuratamente messo in posa, come se il momento dello scatto non derivasse da un istinto irrazionale bensì avesse bisogno di essere assorbito, meditato e solo in un secondo momento ripreso, a seguito di una riflessione sull’equilibrio dell’essere, sul senso di una vita troppo spesso vissuta di fretta e per questo necessitante un’analisi più approfondita, di una riconsiderazione del valore della lentezza che molto spesso nasconde la bellezza, la vera armonia. È proprio il suo essere contemporanea a farle desiderare di andare contro corrente, di legarsi ad atmosfere e ad ambientazioni che possono appartenere a un’epoca come a tante altre perché in fondo, sembra suggerire l’artista, ciò che resta è l’emozione, ciò da cui l’interiorità viene avvolta a dispetto di tutto quanto nell’oggi sembra essere prioritario. Alla corsa all’immagine Maria Grazia Ferri preferisce il significante, ciò che si nasconde oltre il visibile, come se la sua intuizione andasse verso quelle energie sottili che si susseguono sotto la realtà e tessono le trame degli accadimenti mentre gli oggetti restano a guardare.

Il suo mondo onirico e sospeso non può non essere collegato a quella Metafisica che tanta importanza ha avuto nell’arte dei primi anni del Novecento, contrapposta al Surrealismo nelle intenzioni di Giorgio De Chirico proprio per quel suo escludere il mondo degli incubi, del disordine, dell’irrazionalità, per addentrarsi nel concetto dello spazio, dell’essenza che tende a celarsi dentro la presenza apparente, nel collegamento tra l’oggi e lo ieri che avvolge l’osservatore in un’atmosfera romantica ma anche estraniante per l’assenza della presenza dell’essere umano.

Le medesime caratteristiche contraddistinguono le opere a colori di Maria Grazia Ferri; porte invecchiate e crepate dalle intemperie, muri scrostati, fioriere senza più fiori se non il loro ricordo, balconi perfettamente ordinati di case di campagna, sono questi i suoi soggetti preferiti nelle opere fotografiche a colori, che sembrano assistere al trascorrere del tempo, consapevoli del loro essere lì, immoti, spettatori del susseguirsi della vita e testimoni degli accadimenti. Quando tuttavia l’artista rivolge l’attenzione a istanti rubati da ciò che vede intorno a sé allora preferisce il bianco e nero, più narrativo ed efficace a porre l’attenzione su scorci di vita contemporanea da cui, anche in questo caso, cerca di estrapolare il senso più profondo di ciò che a uno sguardo distratto semplicemente apparrebbe. In questa serie il contrasto diventa il pennello attraverso il quale l’artista descrive il suo punto di vista, il suo approccio nei confronti di ciò su cui, qui sì in modo istintivo, lo sguardo si è posato; più definita è l’alternanza tra chiaro e scuro con un utilizzo della luce netto, scolpito, più l’intento è quello di infondere nell’osservatore il senso dell’evidenza della realtà, del focus su tutti i dettagli e i personaggi invisibili che appartengono alla società contemporanea ma che invece esistono, vivono tra l’indifferenza delle persone.

Più sfumata e rarefatta è l’atmosfera, in questo caso usando la luce in maniera sfumata e soffusa, più il desiderio è quello di dar vita a un racconto poetico, romantico tanto quanto il paesaggio naturale protagonista dello scatto.

Il tocco di Maria Grazia Ferri è in ogni caso sempre rapito dalle bellezze intorno a sé, che niente hanno a che vedere con l’inseguimento alla perfezione dell’immagine che contraddistingue la società moderna, soffermandosi sull’intensità e la capacità di trasmettere emozioni di qualcosa di apparentemente inanimato che attraverso la sua Canon Eos 5D riesce a trovare una voce comunicativa per uscire dal silenzio del tempo e dalla distrazione di un individuo troppo impegnato a correre verso l’ottenimento di qualcosa per essere capace di fermarsi a vivere il momento presente.

Appassionata di fotografia da sempre, Maria Grazia Ferri realizza i primi scatti con una macchina Minolta regalatale da suo padre e da quel momento in avanti non smette più di esplorare la realtà attraverso l’emozione che riceve proprio dal piacere di fotografare. È fondatrice e segretaria dell’associazione artistica Circolart, ha all’attivo molte mostre collettive e personali in Emilia Romagna e le sue opere sono inserite nel Catalogo dell’Arte Moderna edito da Giorgio Mondadori, edizione 2021 e nel volume di storia dell’arte contemporanea Alla ricerca della bellezza di Anna Rita Delucca edito da Cordero Editore Genova.

MARIA GRAZIA FERRI-CONTATTI

Email: m.g.ferri74@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MariaGrazia74Ferri

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/m.g.ferri74/

The metaphysical settings suspended in time of photographic art by Maria Grazia Ferri

The contemporary era is characterised by a simplicity and immediacy in reproducing fragments of lived instants that often tend to overshadow the importance of the moment in order to prioritise appearance, the image, rather than substance. Yet there are artists, because only in this way those who approach photography in an intense, poetic and romantic world can be defined, who prefer to dwell on detail, on the slowness and intensity of experience rather than on the haste and urgency to appear. Today’s protagonist uses the camera almost like a paintbrush, transforming a particular, an ordinary detail into something extraordinary.

With the advancement of technological discoveries and studies on image reproduction, which accelerated in that dynamic and lively 20th century that, especially in the first part, brought considerable changes in the artistic and cultural world, began to spread photography, no longer intended only for experts capable of carrying the cumbersome and heavy equipment in use in the previous century, but lighter and more manageable machines were created, making photographic portraiture more accessible to a greater number of people and compared to painting, but also allowing reporters and journalists to document important junctures in the history of the time. Somehow, therefore, in the first decades of the 20th century, an opposition between art and photography was almost created, as a considerable number of artists took a defensive stance and wanted to distance themselves from the new technology, giving rise to Abstractionism, which asserted the priority and supremacy of the plastic gesture over the coldness of a photographic shot. Yet during those non-conformist and subversive years, the two tendencies could not fail to come into contact and influence each other, particularly in one of the most unconventional artistic currents, Surrealism, whose tendency to experiment welcomed two great photographers, Man Ray and Bill Brandt, capable of bringing out the unconscious both by indulging their expressive intuition and by the observed reality whose dark sides they showed to the common eye. From that moment on, photography began to be considered for what it was, namely art, different from the more manual of painting or sculpture, but nonetheless an intense and involving form of expression that continued to be influenced by pictorial currents, taking its cue from them; the mid-19th century generated the wider and most important generation of great photographers of all times, whose shots could not fail to generate emotion, involvement that reached the observer directly, enveloping him in their atmospheres. The romanticism of Robert Doisneau, the irony of Elliot Erwitt, the social investigation of Gianni Berengo Gardin, to name but a few of the masters of black and white, stood side by side with the strong yet immortal and seemingly motionless reportage images of Steve McCurry and the landscape-metaphysical images of Franco Fontana, both leading exponents of colour photography; all in their own way emphasised the versatility of photographic technique and the possibility of making art with their cameras which today are considered outdated. In turn, the Bolognese artist Maria Grazia Ferri embraces the world of colour, as if her concept of photography felt the need to make use of a chromatic range that she uses to highlight the details that are essential to her, those that must be the protagonists of her shots, to which she succeeds in giving an almost fairy-tale connotation, close to the filmographic atmospheres of Tim Burton, in which time is suspended, where there seems to be neither yesterday nor tomorrow, simply the motionless present highlighted by the romantic gaze of the photographer. The objects, the details, are emphasised by a choice of tones that are saturated, full, almost expressionist in their link to emotion, to the feeling that Ferri feels when observing the scenes and that she feels the desire to immortalise; it almost seems as if every detail is carefully posed, as if the moment of the shot did not derive from an irrational instinct, but needed to be absorbed, meditated upon and only later resumed, following a reflection on the balance of being, on the meaning of a life too often lived in haste and for this reason in need of deeper analysis, of a reconsideration of the value of slowness that very often conceals beauty, true harmony.

It is precisely her being contemporary that makes her want to go against the tide, to bind herself to atmospheres and settings that may belong to an era like many others because in the end, the artist seems to suggest, what remains is emotion, that by which the interiority is enveloped in spite of everything that seems to be a priority in today’s world. Rather than the race for the image, Maria Grazia Ferri prefers the signifier, that which is hidden beyond the visible, as if her intuition were going towards those subtle energies that follow one another beneath reality and weave the plots of events while objects stand by and watch. Her dreamlike, suspended world cannot but be linked to that Metaphysical Art that was so important in the art of the early 20th century, opposed to Surrealism in Giorgio De Chirico’s intentions precisely because of its exclusion of the world of nightmares, of disorder of irrationality, in order to delve into the concept of space, of the essence that tends to conceal itself within apparent presence, in the connection between today and yesterday that envelops the observer in an atmosphere that is romantic but also alienating due to the absence of the presence of the human being.

The same characteristics characterise Maria Grazia Ferri’s colour works; weathered doors cracked by the elements, peeling walls, flower boxes with no more flowers but their memory, perfectly ordered balconies of country houses, these are her favourite subjects in her colour photographic works, which seem to witness the passing of time, aware of their being there, motionless, spectators of the succession of life and witnesses of events. When, however, the artist turns her attention to moments stolen from what she sees around her, she prefers black and white, which is more narrative and effective in focusing attention on glimpses of contemporary life from which, again, she tries to extrapolate the deeper meaning of what would simply appear to a distracted gaze. In this series, the contrast becomes the brush through which the artist describes her point of view, her approach to what, in this case instinctively, her gaze has fallen upon; the more defined the alternation between light and dark with a clear, sculpted use of light, the more the intention is to instil in the observer the sense of the evidence of reality, of the focus on all the details and invisible characters that belong to contemporary society but exist, living amidst people’s indifference.

The more shaded and rarefied the atmosphere, in this case using light in a nuanced and suffused manner, the more the desire is to give life to a poetic tale, as romantic as the natural landscape that is the protagonist of the shot. In any case, Maria Grazia Ferri’s touch is always enraptured by the beauty around her, which has nothing to do with the pursuit of the perfection of the image that characterises modern society, dwelling on the intensity and ability to convey the emotions of something apparently inanimate that through her Canon Eos 5D manages to find a communicative voice to break out of the silence of time and the distraction of an individual too busy rushing towards the achievement of something to be able to stop and live the present moment. A lifelong lover of photography, Maria Grazia Ferri took her first shots with a Minolta camera given to her by her father and from that moment on, she never stopped exploring reality through the emotion she receives from the pleasure of photography. She is the founder and secretary of the Circolart art association, has had many group and solo exhibitions in Emilia Romagna and her works are included in the Catalogo dell’Arte Moderna published by Giorgio Mondadori, 2021 edition, and in the contemporary art history book Alla ricerca della bellezza by Anna Rita Delucca published by Cordero Editore Genova.