L’approccio all’osservazione della realtà viene declinato sulla base della sensibilità e della capacità introspettiva di ciascun artista, dando la possibilità a ciascuno di lasciar emergere aspetti e atmosfere che allo sguardo di un altro magari resterebbero più in secondo piano; lo stile più affine a quest’esigenza di narrare scorci di normalità, piccoli dettagli osservati ogni giorno, è quello figurativo poiché è solo parlando un linguaggio facilmente comprensibile, quello dei riferimenti che l’occhio ben conosce, che poi l’autore dell’opera può avvolgere l’immagine delle sensazioni che riceve e di cui diventa interprete. Il protagonista di oggi compie una sottile analisi sull’ordinarietà, mettendo in rilievo tutti quei significati filosofici e psicologici che ne fanno parte, malgrado la sua apparenza di inosservata abitudine.

Intorno alla metà dell’Ottocento cominciò a emergere un nuovo modo di interpretare la realtà, diversamente da quanto accaduto in tutti i secoli precedenti, perché il Realismo si propose non più di dipingere soggetti religiosi o scene epiche o ancora ritratti di appartenenti alla nobiltà e all’aristocrazia, bensì si interessò di quella classe operaia, contadina, di persone meno abbienti che costituivano la maggior parte della popolazione, rappresentandone istanti di quotidianità, ritraendoli al lavoro e osservandone la dignitosa umiltà. Tuttavia l’esecutore della tela non entrava all’interno dell’opera, non lasciava che la sua interpretazione fuoriuscisse dall’osservato, perché ciò su cui si focalizzava era la pura rappresentazione di ciò che veniva colto. Fu solo con il Novecento, le sue rivoluzioni espressive e concettuali partite dalla forza espressiva dei Fauves e poi estese a tutti gli altri movimenti pittorici figurativi, che il sentire dell’autore, l’approfondimento introspettivo, psicologico e filosofico, o semplicemente emozionale, divenne imprescindibile dal dipinto; da quel momento, in tutte le correnti fortemente legate alla narrazione della realtà, non fu più possibile rinunciare a quella mescolanza tra tecnica artistica tradizionale e le innovazioni di pensiero che resero gli artisti liberi di dare il proprio punto di vista, di mostrare uno sguardo insolito eppure incredibilmente più profondo. In particolar modo negli Stati Uniti, un nutrito gruppo di creativi si concentrò proprio sull’osservazione della vita nelle città che stavano cominciando a trasformarsi in metropoli, evidenziandone le criticità, i momenti di socialità ma anche di solitudine che le persone si trovavano ad affrontare, e soprattutto le nuove architetture, i palazzi, i locali in cui si svolgeva la vita dopo il lavoro, o le case dei sobborghi, piene di luce ma anche di silenzio. Il Realismo Americano indagò sulla psicologia dei personaggi, sul progresso che spesso disumanizzava l’uomo e sulla malinconia appartenente inevitabilmente al processo di introspezione e di riflessione su se stesso; di questo genere di atmosfere fu maestro Edward Hopper, le cui immagini statiche collocate in scenari notturni o nelle periferie sottolineavano l’intensità della meditazione sull’epoca a lui contemporanea che permeava le sue tele. Parallelamente, dopo la fine della prima guerra mondiale, un altro movimento pittorico fortemente legato alla realtà, che prese il nome di Precisionismo, si pose come obiettivo quello di mettere in risalto tutti gli aspetti dell’industrializzazione, ritraendo i nuovi paesaggi urbani delle città, profondamente cambiate, con uno sguardo fiducioso e positivo verso il futuro che attingeva all’ottimismo del Futurismo e alla rigorosità geometrica del Cubismo, immettendo nelle opere una sorta di ammirazione per la capacità dell’uomo di aver generato quei cambiamenti epocali. L’artista Stefano Mariani sembra compiere una sintesi tra i due importanti movimenti del Novecento, il Realismo Americano e il Precisionismo, laddove con il primo infonde le sue tele di atmosfera suggestiva andando a stimolare la riflessione e l’occhio dell’osservatore che si sente attratto da immagini familiari,

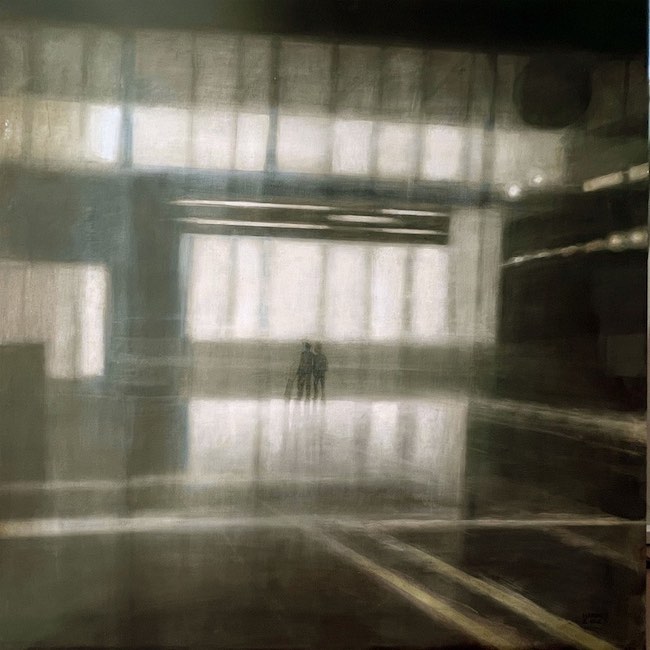

quasi vagando con lo sguardo per riconoscere gli scorci in cui l’uomo appare come semplice parte di una vitale moltitudine che quotidianamente riempie di vita le ambientazioni, mentre con il secondo si sofferma proprio sulle costruzioni dell’uomo, sugli edifici industriali, sui palazzi, sui parcheggi, riempiendo le sue immagini di riflessi, come se egli stesso si fosse trovato a osservare quegli scorci da dietro il vetro di un treno, di una metropolitana o di una finestra, sottintendendo che spesso l’essere umano è un semplice osservatore del prodotto della sua stessa creatività e che ha bisogno di prendere le distanze da ciò in cui è immerso quotidianamente per poterne notare le sfaccettature.

In Stefano Mariani il Precisionismo perde la sua connotazione fortemente geometrica e tende verso una morbidezza che si lega all’introspezione, all’interrogarsi sul ruolo dell’individuo in un mondo in cui la sua stessa presenza sembra essere superflua, quasi trascurabile; impossibile non notare l’interrogativo esistenzialista nei confronti del senso della vita, di quel vagare di persone, laddove la presenza umana faccia parte della tela, che quotidianamente si incrociano e si incontrano senza guardarsi, senza conoscere il volto dell’altro che diviene pertanto solo qualcuno che si muove accanto a sé.

Il pensiero va inevitabilmente verso la considerazione che forse sia proprio a causa di quell’industrializzazione, di quell’espansione selvaggia delle città dove sono stati eretti muri di cemento che si sono generati ostacoli all’umanizzazione, al piacere di incontrarsi e interagire, ciascuno preso dentro le proprie urgenze, i propri obiettivi materiali, i propri drammi quotidiani, per riuscire a ricordare il piacere di rimanere umano nel senso più pieno del termine. Dunque il Realismo diventa approfondimento, meditazione sul senso della vita dell’uomo moderno, di quell’essere parte di una moltitudine che da un lato forse rassicura illudendo di sentirsi meno isolati e parte di un mondo accogliente e inclusivo, dall’altro spersonalizza, appiattisce, omologa le persone che all’interno di quel senso di generalità pensano di sentirsi accettate mentre in realtà dimenticano la propria vera essenza.

Stefano Mariani lascia emergere le luci ma anche le ombre degli scorci urbani che appartengono alla sua produzione, quasi come se l’Esistenzialismo che contraddistingue le atmosfere narrate fosse costantemente in bilico tra positività e negatività, tra ammirazione verso l’innovazione e il progresso, e la sagace analisi delle conseguenze che esso porta con sé, come se non appena rivolge il suo sguardo all’essere umano non possa fare a meno di notarne l’inconsistenza, l’esiguità rispetto a tutto ciò che lo circonda, all’ambiente che abita e che da lui stesso è stato costruito.

Spesso infatti le persone protagoniste delle sue tele sono osservate dall’alto, oppure da lontano, quasi in dissolvenza o confuse negli sfondi, assorbite e fagocitate dai vetri, dal cemento, dai riflessi della città; questa particolarità mette in luce ancor più la sottile antitesi delle opere dell’artista, quell’essere perfettamente calato dentro la realtà contemporanea e al contempo sperare in un risveglio dell’uomo che lo conduca così a tornare a essere primo attore. La gamma cromatica utilizzata da Stefano Mariani è pertanto affine alle sue atmosfere introspettive, si sposta dai toni chiari e sabbiati, che sottolineano l’esistenza della luce, metafora della speranza di un ritorno alla consapevolezza della ricchezza dell’individualità intesa nell’accezione più positiva del termine, a quelli più scuri, in costante penombra, che contraddistinguono i palazzi ma anche le persone perché avvolte dalla sensazione di ordinarietà in cui non riesce a emergere l’eccezionalità di ciascuno.

Gli scenari sembrano essere immortalati nell’atmosfera soffusa dell’alba, quasi a sottolineare quanto ogni giorno possa essere quello giusto per effettuare quel cambiamento, quell’inversione di tendenza che potrebbe modificare ogni cosa, che potrebbe generare una dimensione differente e piena di colori; d’altro canto però, quel giorno si allontana ed è costantemente rinviato perché messo in secondo piano rispetto all’urgenza del compiere i gesti quotidiani, quelli necessari alla sopravvivenza e che costituiscono la rassicurante routine dentro cui l’individuo si nasconde. L’unico modo per valutare una realtà differente, sembra suggerire Stefano Mariani, è quello di allontanarsi e guardare tutto da un vetro, scoprendo impercettibili verità e consapevolezze che non si libereranno mai finché si sarà dentro quella dimensione consueta.

Stefano Mariani, architetto ed esperto di comunicazione visiva oltre che artista, è stato docente di pittura e tromp-l’oeil presso l’Accademia di Arti Visive di Cividale del Friuli. È titolare, dal 1992, della cattedra di Progettazione di Architettura e Ambiente presso il Liceo Artistico Guggenheim di Venezia specializzandosi, nel 2010, nell’insegnamento delle Discipline Audiovisive e Multimediali. Ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a numerose mostre presso gallerie d’arte e ha partecipato a mostre mercato e fiere di arte contemporanea in Italia e all’estero.

STEFANO MARIANI-CONTATTI

Email: marianiste@gmail.com

info@stefanomariani.com

Sito web: https://stefanomariani.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/stefano.mariani.3139

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/stefano_mariani_artworks/

The urban views of Stefano Mariani, when everyday life is enveloped in suggestion

The approach to the observation of reality is declined on the basis of the sensitivity and introspective capacity of each artist, giving each one the possibility of allowing to emerge aspects and atmospheres that would perhaps remain more in the background in the eyes of another one; the style most akin to this need to narrate glimpses of normality, small details observed every day, is the figurative one, since it is only by speaking an easily comprehensible language, that of references which the eye knows well, that the author of the artwork can wrap the image in the sensations he receives and of which he becomes the interpreter. Today’s protagonist makes a subtle analysis of ordinariness, highlighting all those philosophical and psychological meanings that are part of it, despite its appearance of unnoticed habit.

Around the middle of the 19th century began to emerge a new way of interpreting reality, unlike in all the previous centuries, because Realism no longer set out to paint religious subjects or epic scenes or portraits of members of the nobility and aristocracy, but was interested in the working class, the peasantry, the less well-off who made up the majority of the population, depicting moments of everyday life, depicting them at work and observing their dignified humility. However, the executor of the canvas did not enter inside the work, he did not let his interpretation escape the observed, because what he focused on was the pure representation of what was captured. It was only with the 20th century, its expressive and conceptual revolutions that started with the expressive force of the Fauves and then extended to all other figurative painting movements, that the author’s feeling, the introspective, psychological and philosophical, or simply emotional, insight became inseparable from the painting; from that moment on, in all currents strongly linked to the narration of reality, it was no longer possible to renounce that mixture of traditional artistic technique and innovations of thought that made artists free to give their own point of view, to show an unusual and yet incredibly deeper look.

Particularly in the United States, a large group of creative artists concentrated precisely on observing life in the cities that were beginning to turn into metropolises, highlighting their critical aspects, the moments of sociability but also of loneliness that people had to face, and above all the new architecture, the buildings, the places where life took place after work, or the houses in the suburbs, full of light but also of silence.

American Realism investigated the psychology of the characters, the progress that often dehumanised man and the melancholy that inevitably belonged to the process of introspection and self-reflection; Edward Hopper was a master of this kind of atmosphere, whose static images set in nocturnal scenarios or in the suburbs emphasised the intensity of the meditation on his contemporary era that permeated his canvases. At the same time, after the end of the First World War, another pictorial movement strongly linked to reality, who was named Precisionism, set itself the goal of highlighting all aspects of industrialisation, portraying the new urban landscapes of cities, profoundly changed, with a confident and positive look towards the future that drew on the optimism of Futurism and the geometric rigour of Cubism, injecting into his artworks a kind of admiration for man’s ability to have generated those epochal changes.

The artist Stefano Mariani seems to make a synthesis between the two important movements of the 20th century, American Realism and Precisionism, where with the former he infuses his canvases with an evocative atmosphere, stimulating reflection and the eye of the observer who feels drawn to familiar images, almost wandering with his gaze to recognise the views in which man appears as a simple part of a vital multitude that fills the settings with life on a daily basis, while with the second he dwells precisely on man’s constructions, industrial buildings, car parks, filling his images with reflections, as if he himself had found observing those glimpses from behind the glass of a train, an underground or a window, implying that the human being is often a mere observer of the product of his own creativity and that he needs to distance himself from what he is immersed in on a daily basis in order to notice its facets.

In Stefano Mariani, Precisionism loses its strongly geometric connotation and tends towards a softness that is linked to introspection, to the questioning of the role of the individual in a world in which his very presence seems to be superfluous, almost negligible; it is impossible not to notice the existentialist questioning of the meaning of life, of that wandering of people, where human presence is part of the canvas, who daily cross and meet without looking at each other, without knowing the face of the other, who therefore becomes just someone who moves beside. The thought inevitably goes towards the consideration that perhaps it is precisely because of that industrialisation, of that wild expansion of cities where concrete walls have been erected that obstacles to humanisation have been generated, to the pleasure of meeting and interacting, each one caught up in his own urgencies, his own material goals, his own daily dramas, to be able to remember the pleasure of remaining human in the fullest sense of the term. So Realism becomes an in-depth study, a meditation on the meaning of life of modern man, of that being part of a multitude that on the one hand perhaps reassures by deluding into feeling less isolated and part of a welcoming and inclusive world, on the other hand depersonalises, flattens, homogenises people who within that sense of generality think they feel accepted while in reality they forget their own true essence.

Stefano Mariani brings out the lights but also the shadows of the urban glimpses that belong to his production, almost as if the Existentialism that characterises the narrated atmospheres were constantly poised between positivity and negativity, between admiration for innovation and progress, and the shrewd analysis of the consequences it brings with it, as if as soon as he turns his gaze to human beings he cannot help but notice their insubstantiality, their meagreness compared to everything around them, to the environment they inhabit and that they themselves have built. In fact, the people protagonists of his canvases are often observed from above, or from afar, almost fading or blurred in the backgrounds, absorbed and phagocytised by the glass, the concrete, the reflections of the city; this peculiarity highlights even more the subtle antithesis of the artist’s works, that of being perfectly immersed in contemporary reality and at the same time hoping for a reawakening of man that will lead him to become a leading actor once again. The chromatic range used by Stefano Mariani is therefore akin to his introspective atmospheres, shifting from the light and sandy tones that emphasise the existence of light, a metaphor for the hope of a return to the awareness of the richness of individuality understood in the most positive sense of the term, to the darker tones, in constant semi-darkness, that characterise the buildings but also the people because they are enveloped in the feeling of ordinariness in which the exceptionality of each one fails to emerge.

The scenarios seem to be immortalised in the suffused atmosphere of dawn, almost as if to underline how every day could be the right day to make that change, that reversal of trend that could modify everything, that could generate a different dimension full of colour; on the other hand, however, that day recedes and is constantly postponed because it is put in the background compared to the urgency of carrying out daily gestures, those necessary for survival and that constitute the reassuring routine within which the individual hides. The only way to assess a different reality, Stefano Mariani seems to suggest, is to step back and look at everything through a glass, discovering imperceptible truths and realisations that will never be released as long as one is inside that usual dimension. Stefano Mariani, an architect and visual communication expert as well as an artist, has taught painting and tromp-l’oeil at the Academy of Visual Arts in Cividale del Friuli. Since 1992, he has held the chair of Architectural and Environmental Design at the Liceo Artistico Guggenheim in Venice, specialising, in 2010, in the teaching of Audiovisual and Multimedia Disciplines. He has taken part in numerous exhibitions at art galleries and has participated in contemporary art fairs and exhibitions in Italy and abroad.