L’elemento naturale, i luoghi incontaminati in cui l’essere umano si trova da sempre a vivere, hanno costituito fonte di ispirazione per tutti quegli artisti che desideravano porsi in contatto con il proprio io più profondo ma anche raccontare la sensazione di serenità, di rilassatezza che proprio davanti ai paesaggi naturali affioravano nel loro sentire; la scoperta di panorami nuovi e mozzafiato induceva, e induce, questa categoria di artisti fortemente legati alla figurazione e alla rappresentazione delle immagini catturate dallo sguardo e interiorizzate dall’anima, a interpretarne quei piccoli dettagli apparentemente insignificanti ma che in realtà andavano a fissarsi nelle emozioni fino a necessitare di fuoriuscire sulla tela. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi non solo fa dell’osservazione della natura la base principale della sua produzione pittorica, ma immortala anche scorci caratteristici da cui è rimasta affascinata durante i suoi viaggi, scegliendo uno stile legato al passato e con lei fortemente riattualizzato.

Fatta eccezione per la parentesi costituita dal Romanticismo inglese, dove i dipinti di William Turner e John Constable colpirono per la loro forza espressiva e la quasi totale mancanza di presenza umana in un periodo, quello di inizio Ottocento, in cui la pittura era ancora fortemente orientata a rendere protagonista l’uomo attraverso il ritratto o le scene familiari nobili, fu necessario attendere la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo prima che l’Impressionismo giungesse a rompere gli schemi esecutivi e a sovvertire le regole sull’uso del colore e sui soggetti protagonisti delle opere. In particolar modo fu la contemplazione della natura a emergere in maniera netta, in contrasto con l’antecedente Realismo che diede invece rilievo all’essere umano, quello delle classi meno abbienti, quello che lavorava in fabbrica o svolgeva mestieri umili. I maestri impressionisti come Claude Monet, il cui dipinto Impressions au soleil levant segnò ufficialmente la nascita della nuova corrente pittorica, lasciavano invece che lo sguardo vagasse sui paesaggi incontaminati, a volte scorci cittadini, altre invece su luoghi di campagna, come nei dipinti di Camille Pissarro, o sulle sponde del fiume, come nelle affascinanti tele di Alfred Sisley e di Berthe Morisot, lasciandosi avvolgere dalla luce e dalla consistenza delle pennellate date a tocchi lievi e brevi in modo che la contiguità dei colori, non più dunque stesi e mescolati sulla tavolozza, desse il risultato finale più vicino alla realtà. Ciò che emergeva dalle opere di questi maestri, malgrado la loro attenzione fosse rivolta essenzialmente all’estetica, alla riproduzione fedele di quanto lo sguardo riusciva a cogliere nel momento in cui era di fronte al paesaggio immortalato, era però l’atmosfera circostante, la poesia che inevitabilmente usciva dalla tela per entrare in comunicazione con l’interiorità dell’osservatore. L’esperienza dell’Impressionismo fu solo l’inizio non solo della rivalutazione del paesaggismo come forma d’arte di grande valore tanto quanto ne aveva il ritratto, ma anche di quel processo di scomposizione dell’immagine che proseguì con il Postimpressionismo, il Divisionismo per poi divenire la base di partenza dei nuovi sistemi di riproduzione di immagini, sia fotografiche che video, suddivisi appunto in pixel attraverso cui dare il risultato visivo finale. Al di là del successivo periodo di distacco da tutto ciò che fosse riconducibile alla realtà contingente, sancito dall’emergere dell’Arte Astratta, il paesaggio tornò a essere protagonista, a periodi alterni ma soprattutto sulla base dell’indole del singolo autore dell’opera, perché la seconda metà del Novecento fu contraddistinta dalla coesistenza di vari movimenti pittorici e dalla libertà dei creativi di scegliere lo stile più affine al proprio estro. L’artista altoatesina Angela Carboni Monauni non solo rende il paesaggio e l’ammirazione verso la natura i principali protagonisti delle sue opere, ma di fatto compie un balzo indietro nel tempo riprendendo e amplificando il tema della frammentazione delle pennellate tipico dell’Impressionismo e che nella sua pittura si attualizza e asseconda al suo modo di vedere la realtà che intende descrivere e anche al bisogno di scegliere liberamente l’assonanza cromatica che predilige, tralasciando per scelta ogni regola che tenderebbe a farla sentire intrappolata all’interno di uno schema predefinito.

E non solo, Angela Carboni Monauni ama raccontare frammenti di ricordi, di scorci che hanno colpito la sua emotività durante i numerosi viaggi e che poi ha sentito il bisogno di rendere protagonisti assoluti delle sue opere; sì perché lei, tanto quanto faceva Camille Pissarro, frequentemente esclude la presenza umana, come se l’equilibrio e la serenità che riceve dalla natura non possa essere disturbata dalla presenza dell’uomo, troppo spesso una minaccia nei confronti della bellezza e della purezza degli ambienti che lo accolgono.

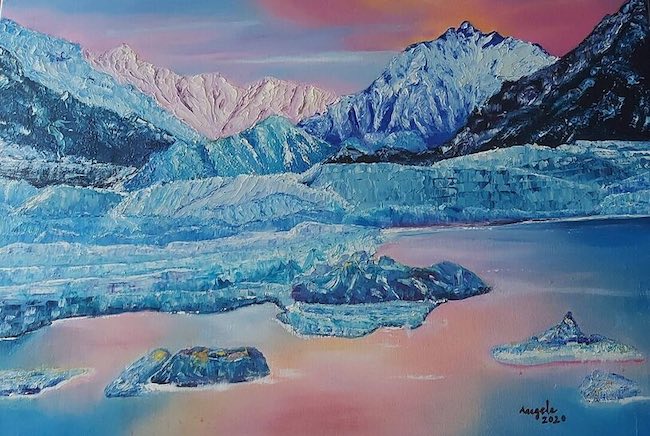

La pennellata è densa e molto breve, in alcune opere talmente consistente da divenire essa stessa fondamentale per determinare le ombre e i rilievi delle immagini, mostrando una tridimensionalità coinvolgente che a volte alterna a una stesura più tradizionale ottenuta mescolando i colori sulla tavolozza; è questo il caso dell’opera Ghiacciaio sul Lago di Tasmania dove il ghiaccio è raccontato appunto con una densità quasi materica, proprio per sottolineare la sua durezza, la resistenza che questo elemento oppone alla corrosione delle acque sottostanti che sembrano calme, morbide, come se divenissero una culla accogliente.

Anche nel cielo la pittura è liscia, sfumata, evoca l’aria fresca di quel luogo incontaminato anche se la parte del giorno descritta è quella del tramonto; il contrasto con la coriaceità della montagna innevata che sembra non lasciarsi intimorire dal calore del sole. In questo dipinto emergono le sensazioni provate da Angela Carboni Monauni nel momento in cui si è trovata di fronte a quel suggestivo paesaggio nell’inverno australiano, il piacere nel lasciarsi trasportare dalla magia di quei colori tenui e avvolgenti, a dispetto del freddo che inevitabilmente aveva accompagnato quella visione.

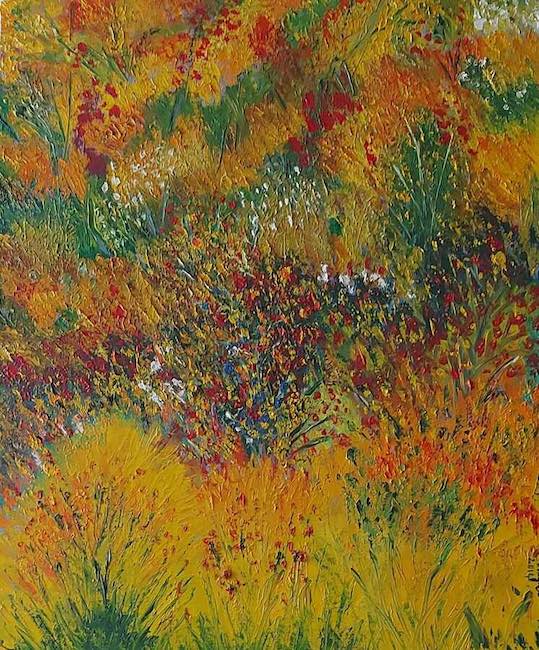

Nella tela Primavera, al contrario, l’artista descrive il risveglio della natura, la fase in cui il freddo invernale lascia il posto a un tepore in virtù del quale le piante ritrovano il loro verde brillante e i fiori rinascono riempiendo ogni luogo di vivaci o teneri colori; lo scorcio descritto potrebbe trovarsi ovunque perché ciò che la Monauni desidera esprimere è solo il senso di vitalità, quella morbidezza poetica che la stagione suscita in chiunque sia in grado di porsi in sensibile posizione di ascolto verso tutto ciò che circonda la vita umana. Qui la pennellata è fortemente impressionista, talmente frammentata da rendere più comprensibile l’immagine generale solo allontanandosi da essa; l’accostamento delle tonalità è digradante soprattutto nella descrizione dei fiori, e contrastante in quella del prato e degli alberi che fanno loro da cornice, come se il verde e il giallo della vegetazione fossero al contempo appartenenti a specie diverse ma fondamentali per infondere vivacità al paesaggio e per dare all’osservatore il senso di meraviglia che l’artista vive ogni volta in cui ammira quel magico posto.

In Autunno astratto racconta della stagione opposta, quella del momentaneo addormentarsi della vegetazione che perde le sue foglie oppure le trasforma modificandone il colore, quasi proteggendosi dalle piogge e dal freddo che di lì a poco giungeranno; la rappresentazione che Angela Carboni Monauni ne fa è comunque gioiosa, consapevole che nell’equilibrio naturale ogni fine non è che il preludio a un nuovo inizio, che la rigenerazione consente di rafforzarsi, di rinascere dalle proprie ceneri per tornare a nuova vita. Sembra quasi una metafora della vita stessa quest’opera in cui ciò che conta è perdersi all’interno di quelle foglie ingiallite e rossastre, di quegli arbusti pronti a entrare in letargo vitale che si scioglierà solo con la fine dell’inverno; eppure l’artista ne sottolinea la bellezza poetica, la vitalità persistente perché in fondo tutta la natura ha un suo equilibrio intrinseco che non può non conquistare con la sua spontaneità.

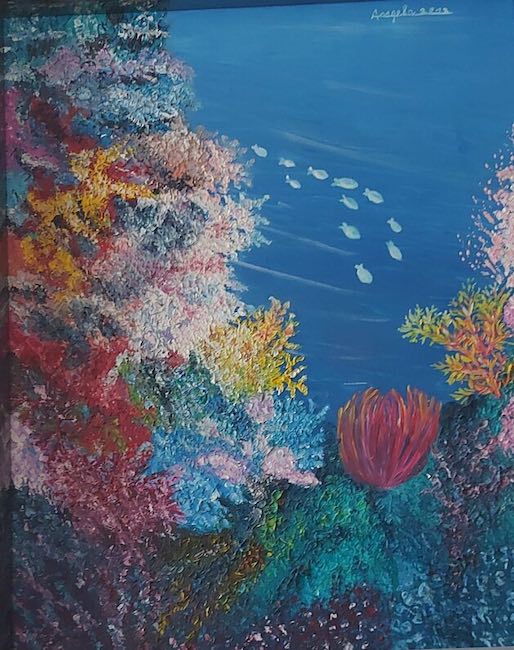

Anche i fondali marini sono spesso protagonisti delle opere di Angela Carboni Monauni, quelli ammirati nei viaggi in Egitto, Hurgada e Sharm el Sheik, ricchi di colori, di pesci variopinti e di meravigliosi coralli e piante che fluttuano con il muoversi delle acque e che nascondono la loro natura resistente e in grado di resistere alla corrosione della salsedine. Ciò che emerge in maniera chiara anche da questa serie di opere è la fascinazione che l’artista subisce ogni volta in cui il suo sguardo si posa sulla natura, in ciascuna delle sue sfaccettature.

Angela Carboni Monauni, dopo aver seguito un corso di studi distante dalla sua passione per l’arte, riprende in mano tele e pennelli diversi anni fa seguendo corsi di vari maestri e oggi espone regolarmente le sue opere con il Club Arcimboldo di Bolzano ricevendo consensi dalla critica e dal pubblico che si lascia conquistare dai suoi paesaggi incontaminati.

ANGELA CARBONI MONAUNI-CONTATTI

Email: angelamonauni@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100087843717214

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/angelacar2123/

The admired contemplation of nature in all its facets in the artworks by Angela Carboni Monauni

The natural element, the uncontaminated places in which human being has always lived, have been a source of inspiration for all those artists who wished to get in touch with their deepest selves but also to recount the feeling of serenity, of relaxation that emerged in their feelings when faced with natural landscapes; the discovery of new and breathtaking panoramas induced, and induces, this category of artists strongly tied to figuration and the representation of images captured by the gaze and internalised by the soul, to interpret those small details that are apparently insignificant but which in reality go on to fix themselves in the emotions to the point of needing to come out on canvas. The artist I am going to tell you about today not only makes the observation of nature the main basis of her pictorial production, but also immortalises characteristic views that she was fascinated by during her travels, choosing a style linked to the past and strongly updated with it.

With the exception of the interlude of English Romanticism, where the paintings of William Turner and John Constable were striking for their expressive force and the almost total lack of human presence in a period, the early 19th century, in which painting was still strongly oriented towards making man the protagonist through portraits or noble family scenes, it was not until the end of the 19th century that Impressionism broke the mould and subverted the rules on the use of colour and the subjects that were the protagonists of the works. In particular, it was the contemplation of nature that emerged sharply, in contrast to the earlier Realism that instead emphasised human beings, those of the lower classes, those who worked in factories or did menial jobs. Impressionist masters such as Claude Monet, whose painting Impressions au soleil levant officially marked the birth of the new pictorial current, instead let their gaze wander over pristine landscapes, sometimes city views, sometimes country scenes, as in the paintings of Camille Pissarro, or on river banks, as in the fascinating canvases of Alfred Sisley and Berthe Morisot, allowing themselves to be enveloped by the light and the texture of the brushstrokes given in light and brief touches so that the contiguity of the colours, no longer spread and mixed on the palette, gave the final result closer to reality. What emerged from the artworks of these masters, despite the fact that their focus was essentially on aesthetics, on the faithful reproduction of what the eye was able to grasp when it was in front of the immortalised landscape, was however the surrounding atmosphere, the poetry that inevitably emerged from the canvas to enter into communication with the interiority of the observer. The experience of Impressionism was only the beginning not only of the re-evaluation of landscape painting as an art form as valuable as the portrait, but also of that process of decomposition of the image that continued with Post-Impressionism, Divisionism and then became the starting point of the new systems of image reproduction, both photographic and video, subdivided precisely into pixels through which the final visual result was achieved. Apart from the subsequent period of detachment from everything that was ascribable to contingent reality, sanctioned by the emergence of Abstract Art, the landscape returned to prominence, in alternating periods but above all on the basis of the temperament of the individual author of the artwork, because the second half of the 20th century was characterised by the coexistence of various painting movements and the freedom of creative artists to choose the style most akin to their own fancy.

The South Tyrolean artist Angela Carboni Monauni not only makes the landscape and admiration for nature the main protagonists of her artworks, but also takes a leap back in time by resuming and amplifying the theme of the fragmentation of brushstrokes typical of Impressionism, which in her painting is brought up to date and is in keeping with her way of seeing the reality she intends to describe and also with the need to freely choose the chromatic assonance she prefers, omitting by choice any rule that would tend to make her feel trapped within a predefined scheme. And not only that, Angela Carboni Monauni loves to recount fragments of memories, of glimpses that have struck her emotionally during her numerous travels and that she then felt the need to make the absolute protagonists of her canvases; yes, because she, as much as Camille Pissarro did, frequently excludes the human presence, as if the balance and serenity she receives from nature cannot be disturbed by the presence of man, too often a threat to the beauty and purity of the environments that welcome it. The brushstroke is dense and very brief, in some works so consistent that it itself becomes fundamental in determining the shadows and reliefs of the images, showing an engaging three-dimensionality that sometimes alternates with a more traditional drafting obtained by mixing colours on the palette; this is the case of the artwork Glacier on Lake Tasmania where the ice is portrayed with an almost material density, precisely to emphasise its hardness, the resistance that this element opposes to the corrosion of the waters below, which seem calm, soft, as if they were becoming a welcoming cradle. Even in the sky, the painting is smooth, shaded, evoking the fresh air of that uncontaminated place even though the part of the day described is that of sunset; the contrast with the leatheriness of the snow-covered mountain that seems not to be intimidated by the warmth of the sun.

In this painting, the sensations felt by Angela Carboni Monauni when she stood in front of that evocative landscape in the Australian winter emerge, the pleasure in letting herself be carried away by the magic of those soft, enveloping colours, in spite of the cold that had inevitably accompanied that vision. In the painting Spring, on the other hand, the artist describes the reawakening of nature, the phase in which the winter cold gives way to a warmth in virtue of which the plants regain their brilliant green and the flowers are reborn, filling every place with vibrant or tender colours; the view described could be found anywhere because what Monauni wishes to express is only the sense of vitality, that poetic softness that the season arouses in anyone capable of placing themselves in a sensitive position of listening to everything that surrounds human life. Here the brushstroke is strongly impressionistic, so fragmented that the overall image can only be more comprehensible if one moves away from it; the combination of tones is degrading, especially in the description of the flowers, and contrasting in that of the meadow and the trees that frame them, as if the green and yellow of the vegetation belonged to different species at the same time but were fundamental to infusing the landscape with liveliness and giving the observer the sense of wonder that the artist experiences every time she admires that magical place. In Abstract Autumn, she tells of the opposite season, that of the momentary falling asleep of vegetation that either loses its leaves or transforms them, changing their colour as if to protect itself from the rain and cold that will soon arrive; the portrayal that Angela Carboni Monauni makes of it is nonetheless joyful, aware that in the natural balance, every end is but the prelude to a new beginning, that regeneration allows one to strengthen oneself, to be reborn from one’s own ashes to return to new life.

It almost seems like a metaphor for life itself in this artwork, in which what matters is to lose oneself within those yellowed and reddish leaves, those shrubs ready to enter into a vital hibernation that will only melt away with the end of winter; yet the artist emphasises their poetic beauty, their persistent vitality because after all, all nature has its own intrinsic balance that cannot fail to conquer with its spontaneity. Even the seabed is often the protagonist of Angela Carboni Monauni‘s works, those admired in her travels to Egypt, Hurgada and Sharm el Sheik, rich in colours, multi-coloured fish and marvellous corals and plants that fluctuate with the movement of the water and conceal their resistant nature, able to withstand the corrosion of the saltiness. What also emerges clearly from this series of paintings is the fascination that the artist undergoes every time her gaze rests on nature, in each of its facets. Angela Carboni Monauni, after having followed a course of studies far removed from her passion for art, took up canvas and paintbrushes again several years ago, following courses with various masters, and today regularly exhibits her works with the Club Arcimboldo in Bolzano, receiving acclaim from critics and the public, who are won over by her unspoilt landscapes.