La società attuale tende verso un’individualità che spesso induce a isolarsi dal mondo circostante, come se la socialità potesse distrarre dal coltivare quelle emozioni singole che sono essenziali per non perdere il contatto con l’interiorità; di fatto questo tipo di atteggiamento si è tradotto in arte con una predisposizione dei creativi a manifestare le proprie sensazioni in maniera soggettiva, tralasciando a volte persino l’ascolto circostante pur di restare connessi con le proprie profondità poi liberate sulla tela. Eppure l’essere umano non può prescindere dalla comunità in cui vive, non può trascurare quanto il suo destino sia legato a quello di chi fa parte della sua vita e quanto la società, intesa nel senso più universale e generale del termine, sia determinante nell’originare anche quei cambiamenti e quelle propagazioni del sentire che da soli non è possibile affrontare. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi mostra, nella serie che andremo a scoprire, un approccio decisamente osservativo nei confronti di quel gruppo di persone che rappresentano esattamente quella generalità, quella comunità di individui che, pur diversi, non possono fare a meno di vivere le stesse vibrazioni.

Nella storia dell’arte vi sono stati molti esempi di opere in cui la collettività era stata inserita nei dipinti, nel caso dei secoli più lontani soprattutto quando rappresentativi di temi religiosi, di allegorie o di ritratti di battaglie epiche; nel Cinquecento vi fu però un precursore di quelle che furono le tematiche della riflessione sull’umanità, il Fiammingo Hieronymus Bosch, che ebbe il coraggio di creare uno stile pittorico inconsueto anche e soprattutto per il significato che dalle sue tele fuoriusciva, quello cioè della rappresentazione di una pluralità legata alle regole del Cristianesimo ma al contempo piena di contraddizioni, di ribellioni segrete che sfociavano in vizi, nell’inevitabile giudizio con speranza di salvezza che apparteneva alla religione. Per riscontrare la medesima attenzione nei confronti dell’uomo inteso come comunità, con le sue necessità di riscatto e con il suo desiderio di far sentire la propria voce, fu necessario attendere qualche secolo, poiché fu attraverso il Realismo, dunque nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento, che gli artisti cominciarono a osservare le classi sociali degli invisibili, quei lavoratori che producevano pur essendo sfruttati e privati dei loro diritti; ma i tempi erano maturi per le lotte sociali e gli esponenti di questo movimento pittorico altrettanto pronti a documentare quelle rivoluzioni e la capacità dell’essere umano di unirsi per generare una forza maggiore di quella del singolo. Il Quarto stato di Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, ma anche tutta la produzione artistica del messicano Diego Rivera, posero l’accento sulle voci degli ultimi, delle persone che volevano conquistare un posto più dignitoso all’interno della società. Pablo Picasso utilizzò il Cubismo anche per raccontare il dolore di un popolo, come nel celeberrimo quadro Guernica, sottolineando le sensazioni condivise in un momento di sofferenza; qualche anno dopo, intorno alla metà del Ventesimo secolo, quando il mondo sembrava aver raggiunto una fase di stabilità, l’arte cominciò a considerare maggiormente le sensazioni individuali, oppure ad alleggerire la sua forma pur non tralasciando di lasciare messaggi sociali di grande spessore. Questo è stato il caso della Pop Street Art di cui Keith Haring fu grande interprete soprattutto nell’accezione della condivisione, della consapevolezza della necessità per l’uomo di fare gruppo e combattere le proprie battaglie di accettazione, nel suo caso specifico quella della sua omosessualità, concretizzate sulla tela dalla presenza dei suoi omini stilizzati, tutti uniti dal medesimo destino come in un reticolo indivisibile.

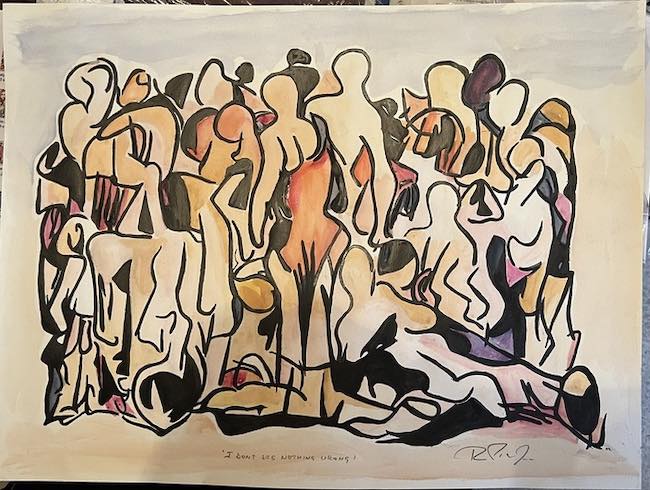

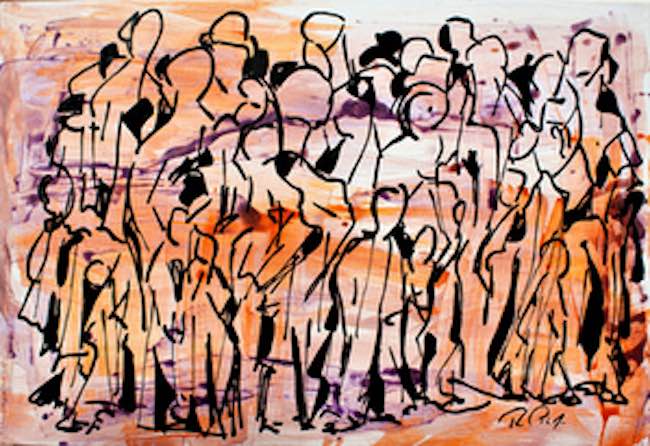

La serie di opere di Ray Piscopo che andremo ad approfondire oggi si lega fortemente a questa tendenza ad ascoltare la comunità, a osservare la moltitudine non più come una minaccia all’individualismo e al sentire del singolo, piuttosto come la consapevolezza della propagazione delle medesime sensazioni davanti ai grandi eventi, o ai grandi temi universali, che l’umanità si trova ad affrontare e a scegliere se accettarli o combatterli; è esattamente in questo delicato momento che si posa lo sguardo di Ray Piscopo, nella fase della presa di coscienza a seguito della quale sarà poi necessario decidere se reagire oppure piegarsi alla circostanza sapendo che potrebbe modificare il corso dell’esistenza comune. Lo stile espressivo è indubbiamente espressionista eppure non si può non notare il riferimento alle figure di Keith Haring, così come la loro inestricabile connessione, che sembrano sottolineare e mettere in evidenza un pensiero condiviso, considerazioni comuni che vanno a generare un’energia dalla quale il singolo difficilmente riesce ad allontanarsi e a cui al contempo non vuole rinunciare, proprio perché il senso di appartenenza e di solidarietà contraddistingue da sempre la natura dell’essere umano.

La gamma cromatica si adegua alle sensazioni evocate dai titoli, che in alcune tele attingono a quelli delle canzoni più famose perché tutto sommato anche la musica è un forte aggregante in grado di creare una profonda connessione energetica tra le persone ma soprattutto è un modo per Ray Piscopo di dare all’osservatore una traccia immediata del concetto che desidera mettere in evidenza, proprio perché la mancanza di dettagli dei suoi personaggi, di quelle moltitudini stilizzate, impedirebbero una comprensione chiara del suo messaggio emozionale.

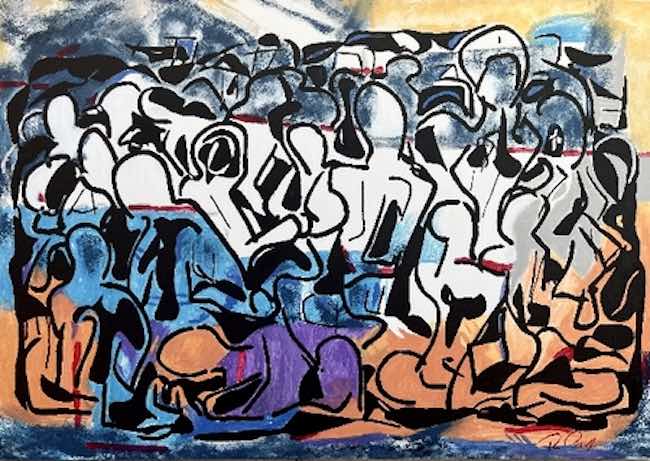

Infatti ciò che fuoriesce in modo inequivocabile è l’emozione, la forza collettiva del sentire, e che viene intuita dalla posizione dei corpi, dalle posture che contribuiscono a sottolineare l’atteggiamento comune o la reazione a una circostanza; in Everybody wants to rule the world sembra che gli omini cerchino di emergere dalla massa, anche a costo di prevaricare chi sta più al di sotto, perché il desiderio di raggiungere l’obiettivo più alto, quello di entrare nella cerchia di chi davvero domina il mondo, è più forte di qualunque senso di umanità e di empatia. I corpi sembrano essere schiacciati per l’allungarsi verso una posizione più favorevole, mentre la gamma cromatica è giocata tra i toni del rosso granato che corrisponde alla determinazione e alla predisposizione a lottare, il giallo che in questa accezione rappresenta l’inganno e la competitività, e infine il blu riservato alla parte più alta, quasi impercettibile, nella declinazione più scura perché in fondo non è affatto detto che quel potere verso cui la massa anela, sia poi portatrice di felicità.

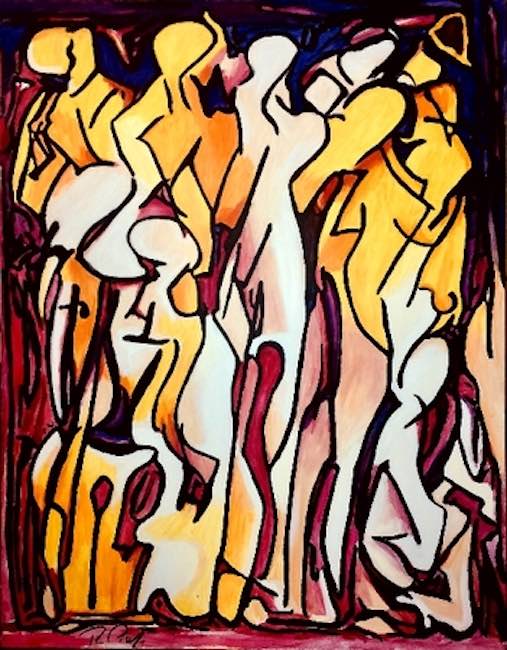

Nella tela In search of reason Ray Piscopo osserva la sofferenza condivisa dalle persone nel momento in cui si trovano di fronte a un evento doloroso, evitabile eppure accaduto per volontà di pochi, e sopraggiunto come un uragano a modificare per sempre il corso delle loro vite o in alcuni casi della storia dell’umanità; sì perché l’artista in questa serie pittorica si interroga sui grandi temi dell’esistenza, quelle domande che troppo spesso rimangono inascoltate e senza una risposta proprio perché sostenute da dinamiche che l’individuo non riesce a concepire, a spiegare o ad accettare come parte di una realtà accaduta. Una ragione spesso non esiste, semplicemente l’ambizione di qualcuno provoca dolore in molti altri, conduce verso scontri, conflitti, guerre che la moltitudine subisce senza aver avuto la possibilità di scegliere; il dripping rosso esalta in maniera netta ma discreta il significato del titolo, così come la posizione di alcuni personaggi è sopraffatta dalle ferite, dal dolore, dall’incredulità che qualcosa di tanto brutto e devastante possa essere accaduto.

Dunque l’aspetto Pop degli omini di Ray Piscopo si allontana dalla leggerezza che si potrebbe credere gli appartenga ed entra in quelle tematiche profonde che fanno parte del vivere contemporaneo e che sono comuni a tutte le persone chiamate a vivere, e a scegliere, nel tempo attuale.

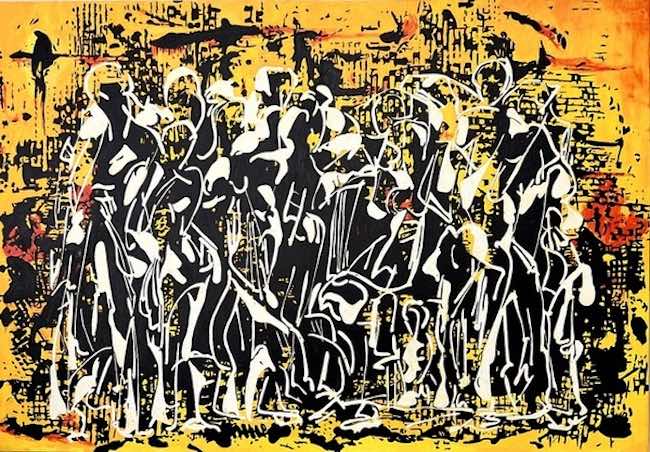

In The wall l’artista affronta il tema della divisione, di quei confini posti per dividere, più che proteggere, tralasciando quanto invece la gente, quella a cui non viene mai chiesta l’opinione, vorrebbe al contrario oltrepassarli per condividere anche le diversità; il riferimento è ovviamente quello del Muro di Berlino, abbattuto ormai nel secolo scorso e tuttavia ancora simbolo di quanto la separazione tra radici vicine e simili possa essere portatrice di sofferenza e di inutili distacchi, quando poi tutto ciò che desidera l’uomo è interfacciarsi e vivere in pace.

Ray Piscopo, artista sensibile e poliedrico, in questa produzione mostra tutto il suo lato più empatico, privo di giudizio nei confronti del popolo che spesso non riesce a comprendere le dinamiche che si muovo al di sopra della sua contingenza, ma lucido nel valutare e mettere in evidenza le mancanze di chi troppo spesso è disposto a tutto pur di ottenere un potere che poi non sa amministrare, provocando dolore e sofferenza; è proprio questo fascino narrativo che rende Ray Piscopo ambìto dai collezionisti che lo seguono nelle sue mostre a Malta e all’estero.

RAY PISCOPO-CONTATTI

Email: piscopoart@gmail.com

Sito web: www.piscopoart.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/ray.piscopo

Instagram: www.instagram.com/raypiscopo/

The emotional cry of the multitude in Ray Piscopo’s Expressionist Pop Art, between divisions and inclusions reflecting on the complexity of contemporaneity

Today’s society tends towards an individuality that often induces to isolate oneself from the surrounding world, as if sociality could distract from cultivating those individual emotions that are essential for not losing contact with one’s interiority; in fact, this type of attitude has been translated into art with a predisposition of creatives to manifest their sensations in a subjective manner, sometimes even neglecting to listen to the surrounding world in order to remain connected with their own depths then released on canvas. Yet the human being cannot disregard the community in which he lives, cannot overlook how much his destiny is linked to that of those who are part of his life, and how much society, understood in the most universal and general sense of the term, is decisive in originating even those changes and propagations of feeling that cannot be tackled alone. The artist I am going to tell you about today shows, in the series we will discover, a decidedly observational approach to that group of people who represent exactly that generality, that community of individuals who, although different, cannot help but experience the same vibrations.

In the history of art, there have been many examples of artworks in which the collective was included in the paintings, in the case of the earlier centuries especially when representing religious themes, allegories or portraits of epic battles; in the 16th century, however, there was a forerunner of what became the themes of reflection on humanity, the Flemish artist Hieronymus Bosch, who had the courage to create an unusual pictorial style also and above all because of the meaning that emerged from his canvases, that of the representation of a plurality linked to the rules of Christianity but at the same time full of contradictions, of secret rebellions that resulted in vices, in the inevitable judgement with hope of salvation that belonged to religion. To see the same attention paid to man as a community, with his need for redemption and his desire to make his voice heard, it was necessary to wait a few centuries, since it was through Realism, in the second half of the 19th century, that artists began to observe the social classes of the invisible, those workers who produced despite being exploited and deprived of their rights; but the time was ripe for social struggles and the exponents of this pictorial movement were just as ready to document those revolutions and the ability of human beings to unite to generate a force greater than that of the individual.

The Fourth Estate by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, but also the entire artistic production of the Mexican Diego Rivera, emphasised the voices of the last, of people who wanted to gain a more dignified place in society. Pablo Picasso used Cubism also to narrate the pain of a people, as in the very famous painting Guernica, emphasising the shared feelings in a moment of suffering; a few years later, around the middle of the 20th century, when the world seemed to have reached a stage of stability, art began to consider individual feelings more, or to lighten its form while not neglecting to leave social messages of great depth. This was the case of Pop Street Art, of which Keith Haring was a great interpreter, especially in the sense of sharing, of the awareness of the need for man to form a group and fight his own battles of acceptance, in his specific case that of his homosexuality, concretised on the canvas by the presence of his stylised little men, all united by the same destiny as in an indivisible network. The series of works by Ray Piscopo that we are going to explore today is strongly linked to this tendency to listen to the community, to observe the multitude no longer as a threat to the individualism and feeling of the single, but rather as the awareness of the propagation of the same feelings in the face of the great events, or the great universal themes, that humanity has to face and to choose whether to accept or fight them; it is precisely in this delicate moment that Ray Piscopo’s gaze rests, in the phase of awareness following which it will then be necessary to decide whether to react or to bow to the circumstance knowing that it could alter the course of common existence. The expressive style is undoubtedly expressionist, yet one cannot fail to notice the reference to Keith Haring’s figures, as well as their inextricable connection, which seem to emphasise and highlight a shared thought, common considerations that generate an energy from which the individual finds it difficult to distance himself and which at the same time he does not want to renounce, precisely because the sense of belonging and solidarity has always characterised the nature of the human being.

The chromatic range adapts to the sensations evoked by the titles, which in some canvases draw on those of the most famous songs because, after all, music is also a strong aggregator capable of creating a profound energetic connection between people, but above all it is a way for Ray Piscopo to give the observer an immediate trace of the concept he wishes to highlight, precisely because the lack of detail of his characters, of those stylised multitudes, would prevent a clear understanding of his emotional message. Indeed, what emerges unequivocally is the emotion, the collective force of feeling, and this is intuited by the position of the bodies, by the postures that contribute to underlining the common attitude or reaction to a circumstance; in Everybody wants to rule the world it seems that the little men try to emerge from the masses, even at the cost of prevaricating those who are lower down, because the desire to achieve the highest objective, that of entering the circle of those who really dominate the world, is stronger than any sense of humanity and empathy. The bodies seem to be crushed as they stretch towards a more favourable position, while the chromatic range is played out between shades of garnet red, which corresponds to determination and the predisposition to fight, yellow, which in this meaning represents deception and competitiveness, and finally blue, reserved for the highest, almost imperceptible part, in the darkest declination because in the end it is by no means certain that that power towards which the masses yearn is then the bearer of happiness.

In the canvas In search of reason, Ray Piscopo observes the suffering shared by people when they are faced with a painful event, avoidable but nevertheless happened by the will of a few, and has arrived like a hurricane to change the course of their lives or in some cases the history of humanity forever; yes, because the artist in this pictorial series questions the great themes of existence, those queries that all too often go unheard and unanswered precisely because they are sustained by dynamics that the individual is unable to conceive, explain or accept as part of a reality that has happened. A reason often does not exist, simply someone’s ambition causes pain in many others, leads towards clashes, conflicts, wars that the multitude suffers without having had the chance to choose; the red dripping clearly but discreetly enhances the meaning of the title, just as the position of some characters is overwhelmed by the wounds, the pain, the disbelief that something so ugly and devastating could have happened.

So the Pop aspect of Ray Piscopo’s little men moves away from the lightness that one might believe belongs to them and enters into those profound themes that are part of the contemporary living and that are common to all people called upon to live, and to choose, in the present time. In The Wall, the artist tackles the theme of division, of those borders set up to divide rather than protect, overlooking the fact that people, those who are never asked for their opinion, would instead like to cross them in order to share their differences; the reference is obviously to the Berlin Wall, demolished last century and yet still a symbol of how separation between close and similar roots can be the bearer of suffering and useless detachment, when all man wants is to interface and live in peace. Ray Piscopo, a sensitive and multifaceted artist, shows in this production all his more empathetic side, devoid of judgement towards the people who often fail to understand the dynamics that move above their contingency, but lucid in assessing and highlighting the shortcomings of those who are all too often willing to do anything to obtain a power that they do not know how to administer, causing pain and suffering; it is precisely this narrative charm that makes Ray Piscopo coveted by collectors who follow him in his exhibitions in Malta and abroad.