Oltrepassare il confine con la realtà per spingersi verso un universo completamente differente è una caratteristica di alcuni artisti contemporanei che si spingono a immaginare qualcosa di differente rispetto all’osservato, a ipotizzare un canale percettivo che vada oltre il visibile e conduca l’osservatore a interrogarsi sulle sottigliezze delle destabilizzazioni che l’esecutore dell’opera presenta davanti al suo sguardo. La protagonista di oggi osserva il mondo intorno a sé come se fosse una favola da esplorare e interpretare anche attraverso quel sottile mistero che tanto aveva affascinato molti maestri del secolo scorso.

Il Novecento ha tracciato solchi profondi nella storia dell’arte, riprendendo, ampliando e reinterpretando le anticipazioni di alcuni precursori che ebbero il coraggio di essere voci fuori dal coro dei secoli precedenti e che si erano spinti a rappresentare la dimensione della spiritualità, della connessione con un mondo emozionale o naturale troppo spesso ignorato dagli altri movimenti coevi; la Metafisica e il Surrealismo in fondo si ispirarono al Simbolismo ottocentesco e alle visioni di Hieronymus Bosch, prendendoli come spunto per procedere nell’indagine nei confronti dell’inspiegabile e degli enigmi della realtà attuale e per indagare l’inconscio, la dimensione onirica e le inquietudini umane. Le atmosfere quasi immobili e prive della presenza umana di Giorgio De Chirico, che stimolavano la riflessione nei confronti di un tempo sospeso tra passato e presente dove l’uomo in fondo è solo un protagonista effimero e transitorio, si collegavano in qualche modo all’indagine sull’essenza umana compiuta da René Magritte che si focalizzava non tanto sulle inquietudini e le angosce di un subconscio ingovernabile quanto invece sull’ironia della consapevolezza della totale mancanza di capacità di osservarsi in maniera approfondita, di dare un senso a tutti quegli automatismi dell’esistenza che presi singolarmente hanno un loro intimo significato. Il tema esistenzialista fu ripreso anche dal Realismo Magico dove però la rappresentazione della figura umana tornò a essere centrale, protagonista di emozioni e sensazioni che solo l’autore dell’opera riusciva a cogliere e a raccontare nella loro pienezza all’osservatore. Con il susseguirsi dei decenni l’approccio all’arte si modificò, cambiò la sua essenza mescolando a tutte le radici precedenti per dare vita a stili inediti, in cui la cultura popolare, base di partenza imprescindibile della Pop Art e della Street Art, si allargò a tutti gli altri mezzi di comunicazione come il cinema, i fumetti, la musica, la fotografia, creando linguaggi in grado di arrivare in maniera più diretta a un pubblico molto più vasto rispetto all’ambiente circoscritto degli appassionati d’arte. Intorno alla metà degli anni Settanta nacque il Pop Surrealismo, detto anche Lowbrow, un movimento pittorico che di fatto fuse le tematiche del Surrealismo, del Simbolismo e del Realismo Magico, permettendo agli artisti aderenti di generare atmosfere irreali, di dar vita a dimensioni fiabesche e gotiche in cui il bene e il male si affiancano e in cui l’apparenza nasconde risvolti molto più complessi rispetto a ciò che emerge a un primo sguardo. In un certo senso Lewis Carrol con il suo Alice nel paese delle meraviglie, fu precursore di uno stile che poi fu magistralmente reinterpretato da uno dei maggiori registi che ha dedicato la sua produzione a questo genere, Tim Burton. Esponente del Pop Surrealismo è l’artista giapponese Shiori Matsumoto, formatasi presso la Kyoto Saga University of Art e affascinata dall’arte fin da bambina, quando leggeva i libri del padre attraverso i quali sognava mondi fantastici grazie alle immagini che scorrevano sotto i suoi occhi; dopo essersi specializzata nella tecnica a olio su tela comincia a delinearsi il suo percorso espressivo che la conduce a dar vita a un universo costituito essenzialmente da bambine, associate all’innocenza e alla capacità di sognare, che però hanno mostrano sempre un’ambivalenza, un aspetto distaccato dalla realtà e in qualche modo enigmatico, come se nascondessero un significato differente da quello mostrato dalla loro estetica impeccabile.

Nelle tele di Shiori Matsumoto emerge costantemente l’aspetto inquietante, quello che si insinua sottilmente nella realtà e che viene rappresentato attraverso gli sguardi criptici, come se nascondessero segreti, come se volessero intendere tutt’altro rispetto a ciò che appare; non solo, le atmosfere raccontate sono fiabesche e al tempo stesso legate alla cultura dark, riconducibili proprio ai personaggi di Tim Burton che pur nel loro aspetto a volte sinistro si rivelano invece positivi.

Nelle tele della Matsumoto avviene l’esatto opposto, dunque malgrado l’aspetto formalmente armonioso e impeccabile le sue protagoniste sembrano rivelare sempre un aspetto negativo, inquietante, che induce l’osservatore a cercare il vero senso, il significato di tutti gli elementi che compongono le opere e il messaggio nascosto nello sguardo delle protagoniste.

La sensazione di straniamento tipica del Realismo Magico, qui viene ampliata e trasformata in ambiguità espressa attraverso gli occhi, sempre magnetici, delle bambine, che combinano l’apparente innocenza a una realtà circostante che conduce inevitabilmente in un mondo parallelo in cui ciò che viene abitualmente considerato sbagliato sembra diventare possibile e quasi accettabile. È proprio qui che emerge il Surrealismo di Shiori Matsumoto, in quel labile equilibrio tra le angosce del vivere contemporaneo e la possibilità di esorcizzarle trasportando tutto nell’universo della fiaba gotica, quel mondo dove le convenzioni sono sovvertite e i valori completamente modificati.

La tela Lullaby è perfettamente affine a questo concetto dove la purezza dell’infanzia viene associata a un aspetto dark della bambina che tiene in mano una bambola con gli spilli, tipica dei riti voodoo del Sud America, quasi come se in qualche modo volesse proteggersi dalle brutture del mondo, dai pericoli di una società attuale dove ogni cosa ha perso il senso originario; da un altro punto di vista però, quello più cupo, la realtà potrebbe essere completamente differente, potrebbe essere la fanciulla stessa a lasciar scaturire emozioni negative nei confronti di una rivale, di qualcuno che l’ha ferita e così il suo atteggiamento da difensivo può facilmente trasformarsi in aggressivo.

Nell’opera Meal for Angelize invece la bambina protagonista si trova nell’oltre, in quel dopo la vita che però da Shiori Matsumoto viene semplicemente indicata come un’altra dimensione possibile, un luogo dove attraverso la sua visionarietà e l’arte può concretizzarsi un modo di vivere differente, fiabesco e forse auspicabile; la guida invisibile sembra indicare alla giovane come procedere per ottenere lo stato angelico a cui lei anela, e la colomba è messaggero di quell’entità invisibile accomunabile alla guida spirituale alla quale l’essere umano ha bisogno di affidarsi. La benda sugli occhi suggerisce l’atteggiamento di fiducia necessario a compiere il passaggio verso una coscienza superiore, lasciando da parte le convenzioni e aprendosi a compiere quel salto nel buio troppo spesso considerato come un rischio e che invece costituisce di solito un benefico passo in avanti verso l’evoluzione.

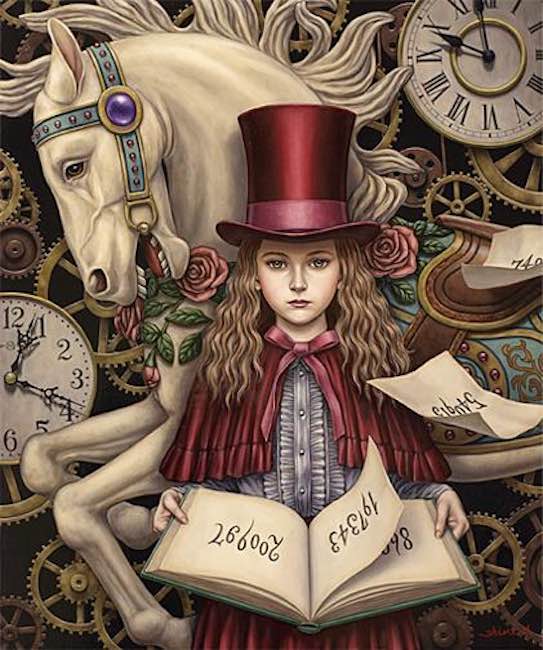

In The page of time, Shiori Matsumoto ammicca ad Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie, dove era però Gianconiglio a essere ossessionato dal tempo; nell’opera al contrario la protagonista sembra invece tranquilla, consapevole dell’ineluttabilità di uno scorrere che non può essere fermato, né inseguito, semplicemente vissuto prima di trovarsi a divenire solo osservatori, o solo piccole parti dell’ingranaggio della vita. Lo sguardo della bambina è piamente consapevole dell’importanza dell’assaporare ogni istante e appare quasi un monito nei confronti dell’osservatore, una sfida a prendere in mano il proprio destino prima che diventi troppo tardi.

Anche l’opera The castle in the Sky è dominata dal tempo, il grande orologio alle spalle delle gemelle che diviene una finestra su quel cielo di cui racconta il titolo, che pur evocando un mondo celestiale si delinea invece come un realtà comune, costituita da giochi, da carte, da cavalli a dondolo che però le due bambine trascurano, come se fossero annoiate perché attratte da altro ma senza la possibilità di scappare dalle mura del luogo in cui vivono. Sembrano darsi coraggio e sostenersi a vicenda tenendosi per mano, pronte ad approfittare del primo momento giusto per raggiungere quel cielo che dall’interno del loro castello possono solo guardare. Shiori Matsumoto espone le sue opere in tutto il mondo affascinando addetti ai lavori, collezionisti e il suo pubblico di appassionati.

SHIORI MATSUMOTO-CONTATTI

Email: shiori@art.email.ne.jp

Sito web: http://www.ne.jp/asahi/secret/label/index.html

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/shiori.matsumoto.5

Twitter: https://twitter.com/pinebookmark

The magical and enigmatic dimension of Shiori Matsumoto’s Pop Surrealism

To go beyond the boundary of reality to a completely different universe is a characteristic of some contemporary artists who go so far as to imagine something different from what is observed, to hypothesise a perceptive channel that goes beyond the visible and leads the observer to question the subtleties of the destabilisations that the executor of the artwork presents before his gaze. Today’s protagonist observes the world around her as if it were a fairytale to be explored and interpreted also through that subtle mystery that so much fascinated many masters of the last century.

The 20th century traced deep furrows in the history of art, taking up, extending and reinterpreting the anticipations of certain precursors who had the courage to be voices outside the chorus of the previous centuries and who had gone so far as to represent the dimension of spirituality, of the connection with an emotional or natural world too often ignored by other contemporary movements; Metaphysics and Surrealism were basically inspired by 19th-century Symbolism and by the visions of Hieronymus Bosch, taking them as their cue to proceed in their investigation of the inexplicable and the enigmas of current reality and to explore the unconscious, the dream dimension and human anxieties. Giorgio De Chirico‘s almost motionless atmospheres devoid of human presence, which stimulated reflection on a time suspended between past and present where man is basically only an ephemeral and transitory protagonist, were in some way connected to René Magritte‘s investigation of the human essence, which focused not so much on the anxieties and anguishes of an ungovernable subconscious as on the irony of the awareness of the total lack of capacity to observe oneself in depth, to make sense of all those automatisms of existence that taken individually have their own intimate meaning. The existentialist theme was also taken up by Magic Realism, where, however, the representation of the human figure returned to be central, the protagonist of emotions and sensations that only the author of the work was able to grasp and recount in their fullness to the observer. As the decades went by, the approach to art was modified, its essence changed, mixing with all its previous roots to give life to new styles, in which popular culture, the inescapable starting point of Pop Art and Street Art, was extended to all the other media such as cinema, comics, music and photography, creating languages capable of reaching a much broader audience in a more direct manner than the circumscribed environment of art lovers. Around the mid-1970s, Pop Surrealism, also known as Lowbrow, a pictorial movement that in fact fused the themes of Surrealism, Symbolism and Magic Realism, allowing the adhering artists to generate unreal atmospheres, to give life to fairy-tale and gothic dimensions in which good and evil stand side by side and in which appearances conceal implications much more complex than what emerges at first glance.

In a way, Lewis Carrol, with his Alice in Wonderland, was the forerunner of a style that was later masterfully reinterpreted by one of the greatest directors who dedicated his production to this genre, Tim Burton. Exponent of Pop Surrealism is the Japanese artist Shiori Matsumoto, trained at the Kyoto Saga University of Art and fascinated by art since childhood, when she read her father’s books through which she dreamt of fantastic worlds thanks to the images that flowed before her eyes; after specialising in the oil on canvas technique, her expressive path began to take shape, leading her to create a universe made up essentially of little girls, associated with innocence and the ability to dream, who, however, always displayed an ambivalence, an appearance detached from reality and somehow enigmatic, as if they were hiding a different meaning from the one shown by their impeccable aesthetics. In Shiori Matsumoto‘s canvases, constantly emeges the disturbing aspect, the aspect that subtly insinuates itself into reality and that is represented through cryptic glances, as if they were hiding secrets, as if they wanted to mean something other than what they appear; not only that, the atmospheres told are fairy-tale and at the same time linked to the dark culture, referable precisely to Tim Burton‘s characters who, despite their sometimes sinister appearance, turn out to be positive instead. In Matsumoto‘s canvases happens the exact opposite, so despite their formally harmonious and impeccable appearance, her protagonists always seem to reveal a negative, disturbing aspect, which induces the observer to search for the real meaning, the significance of all the elements that make up the works and the message hidden in the protagonists’ gaze. The feeling of estrangement typical of Magic Realism is here expanded and transformed into ambiguity expressed through the always magnetic eyes of the girls, who combine apparent innocence with a surrounding reality that inevitably leads into a parallel world in which what is habitually considered wrong seems to become possible and almost acceptable.

It is precisely here that emerges Shiori Matsumoto‘s Surrealism, in that precarious balance between the anxieties of contemporary living and the possibility of exorcising them by transporting everything into the universe of the gothic fairy tale, that world where conventions are subverted and values completely changed. The canvas Lullaby is perfectly akin to this concept where the purity of childhood is associated with a dark aspect of the little girl holding a doll with pins in her hand, typical of South American voodoo rites, almost as if in some way she wanted to protect herself from the ugliness of the world, from the dangers of a current society where everything has lost its original meaning; from another point of view, however, the darker one, the reality could be completely different, it could be the maiden herself who triggers negative emotions towards a rival, towards someone who has hurt her, and so her attitude can easily turn from defensive to aggressive. In the painting Meal for Angelize, on the other hand, the child protagonist finds herself in the beyond, in that after-life which Shiori Matsumoto simply indicates as another possible dimension, a place where, through her visionary nature and art, can be realised a different, fairytale-like and perhaps desirable way of life; the invisible guide seems to show the young girl how to proceed in order to achieve the angelic state she yearns for, and the dove is the messenger of that invisible entity comparable to the spiritual guide to whom the human being needs to rely on. The blindfold suggests the attitude of trust necessary to make the transition to a higher consciousness, leaving aside conventions and opening oneself to take that leap into the dark that is too often considered a risk and that instead usually constitutes a beneficial step towards evolution.

In The Page of Time, Shiori Matsumoto winks at Alice in Wonderland, in which it was, however, Gianconiglio who was obsessed by time; in the artwork on the contrary, the protagonist seems calm, aware of the inevitability of a flowing that cannot be stopped, nor pursued, simply experienced before becoming only observers, or only small parts of the cog of life. The child’s gaze is piously aware of the importance of savouring each moment and appears almost as a warning to the observer, a challenge to take one’s destiny into one’s own hands before it becomes too late. The canvas The castle in the Sky is also dominated by time, the large clock behind the twins becoming a window on that sky of which the title speaks, which, while evoking a celestial world, is instead delineated as a common reality, made up of games, cards, rocking horses that the two girls neglect, as if they were bored because they were attracted by something else but without the possibility of escaping from the walls of the place where they live. They seem to give each other courage and support by holding hands, ready to take advantage of the first right moment to reach that sky that they can only watch from inside their castle. Shiori Matsumoto exhibits her artworks all over the world, captivating experts, collectors and her passionate audience.