Esistono artisti che non possono fare a meno di posare il loro sguardo sulla realtà, perché è proprio partendo da essa che riescono a immaginare i tempi di un passato recente di cui mantenere valori e sensazioni più puri, meno disincantati, pieni ancora di quella magia di un mondo tutto da costruire, da assaporare, trasformando così la pittura in occasione per l’osservatore di evocare immagini e ambientazioni non così lontane da non poter essere recuperate e rivissute con lo stesso approccio. Il protagonista di oggi sceglie uno stile fortemente figurativo a cui infonde un aspetto quasi rarefatto a volte, per osservare una realtà sospesa nel passato, tra realtà e piacevolezza della vita riscontrabile in piccole abitudini apparentemente ordinarie che però erano in grado di dare un senso più pieno all’esistenza.

Tra la fine del Diciannovesimo e gli inizi del Ventesimo secolo cominciò a emergere negli artisti statunitensi un’attenzione particolare nei confronti della classe operaia, della vita comune ben distante dai salotti aristocratici che non avevano nulla di interessante e stimolante, soprattutto perché le trasformazioni che stavano emergendo nella società dell’epoca erano visibili proprio in quella società di sottofondo che viveva, si divertiva, ricostruiva le variegate caratteristiche dei paesi di provenienza, essendo la società statunitense costituita da una grande numero di lavoratori immigrati. Un nutrito gruppo di artisti operanti tra Philadelphia e New York decisero di riunirsi e di creare linee guida comuni che si concretizzarono nella Scuola di Ashcan, di fatto l’inizio di quel Realismo Americano che ha regalato eccezionali talenti alla storia dell’arte, uno fra tutti Edward Hopper. In questo movimento ciò che emergeva in modo chiaro, a parte le differenti interpretazioni di ciascun esponente, era lo spaccato su una società in corso di modificazione, una classe economica che si stava lentamente sollevando, stava guadagnando capacità di acquisto e dunque cominciava a dettare le regole del tempo libero, del divertimento, accordandosi a un’indole sicuramente più popolare eppure più spensierata, in grado di godere appieno di tutto ciò che i loro mezzi potevano offrire. Gli scorci cittadini e panoramici di George Bellows erano uno sguardo affascinato e consapevole sulle evoluzioni che le città statunitensi, in particolare New York, stavano subendo proprio grazie a quella moltitudine di nazionalità, di abitudini culturali e di vita opposte che arricchivano reciprocamente le persone e che riempivano le strade, le spiagge, i luoghi in cui i lavoratori potevano andarsi a divertire, come gli incontri di boxe a cui Bellows dedicò molte tele. John Sloan invece era affascinato dalle atmosfere notturne, dai locali in cui la gente si intratteneva, i teatri, le sale da ballo, o dai momenti in cui le donne uscivano per andare a fare le piccole spese quotidiane, per incontrare le amiche, insomma, raccontò un mondo sereno e vivace, pieno di speranza verso il futuro. Al contrario Eward Hopper, con la sua abilità nell’uso della luce, raccontò della solitudine dell’uomo dell’America degli anni Cinquanta, la sottile linea malinconica con cui sottintendere che in fondo, malgrado le maggiori possibilità economiche della middle class, la felicità non risiedeva nel benessere economico piuttosto andava ricercata nella risoluzione di quelle insicurezze, di quella inspiegabile malinconia che non potevano fare a meno di emergere una volta chiuso fuori il mondo. L’artista canadese Brent Lynch presenta nella contemporaneità uno sguardo nostalgico nei confronti delle atmosfere di quegli anni a metà del Ventesimo secolo in cui la raffinatezza, l’eleganza e la forma erano considerati valori importanti, in cui la musica e il ballo erano espressioni dell’anima e anche un’occasione per lasciarsi trasportare dalle magiche note in un’atmosfera affascinante e fumosa all’interno della quale poter fare incontri, scoprire un mondo differente da quello del giorno e lasciarsene conquistare, per una notte o per sempre.

Le sue opere raccontano dell’importanza degli incontri, della rilevanza della coppia come condizione ideale per l’esistenza, malgrado le fasi di staticità, di ripetitività che spesso emergono dalle sue tele; eppure i suoi personaggi non sembrano voler uscire dalla loro condizione perché forse in fondo, a dispetto di tutto, è l’unica in cui sentono di voler stare.

Questo suo punto di vista viene evidenziato dall’attitudine a produrre le scene sotto forma di dittico, come a sottintendere che la vita può essere condotta in solitudine o in coppia, lasciando all’osservatore la facoltà di scegliere se osservare l’insieme, considerandone l’armonia magica che si sprigiona, oppure separatamente laddove però non si può non notare la sensazione che qualcosa manchi.

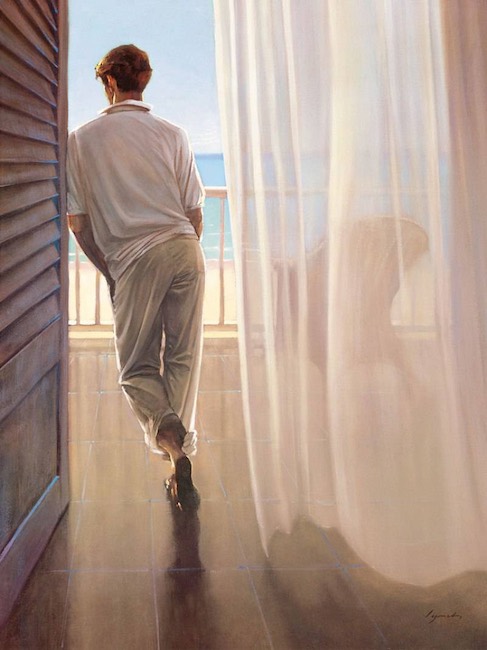

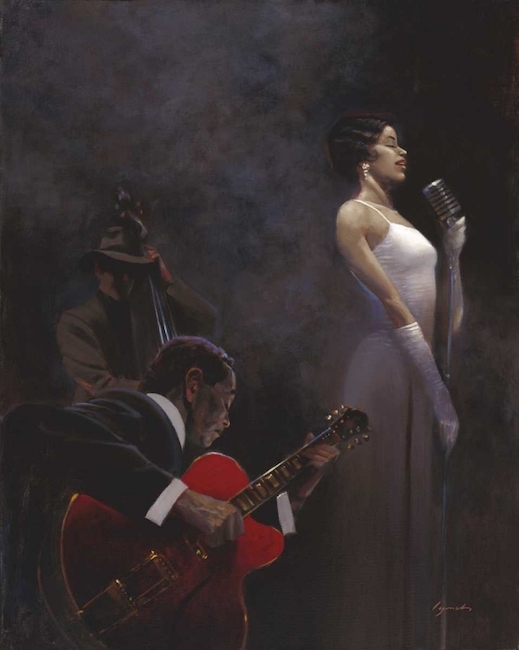

Il suo stile pittorico è fortemente realista e la luce è utilizzata sulla base delle sensazioni che Brent Lynch desidera esprimere, più chiara e leggera nelle ambientazioni in cui vuole far emergere un maggiore romanticismo, quelle atmosfere di magica condivisione in cui tutto ciò che è intorno ai personaggi sembra contribuire a creare l’idillio che avvolge le coppie glamour che ama ritrarre; invece nelle opere in cui affida al fascino della notte e della musica il compito narrativo, allora sceglie le ombre, le velature, il buio suggestivo dentro cui perdersi e immergersi per lasciarsi trascinare dal ritmo, dalle note, dal fumo dei bar di cui descrive gli scorci.

Il mondo notturno è perfettamente rappresentato dai locali di jazz in cui colloca affascinanti cantanti, come nelle tele Pearlescent Diva in cui la donna appare fiera, sicura di sé ma soprattutto trasportata dalle melodie che è chiamata a interpretare; i musicisti sono in penombra, come se la loro presenza fosse funzionale solo a esaltare l’immagine della protagonista su cui Lynch punta il focus, l’occhio di bue pittorico, sottolineandone il coinvolgimento nell’atto forse più affine alla sua natura, quello del cantare.

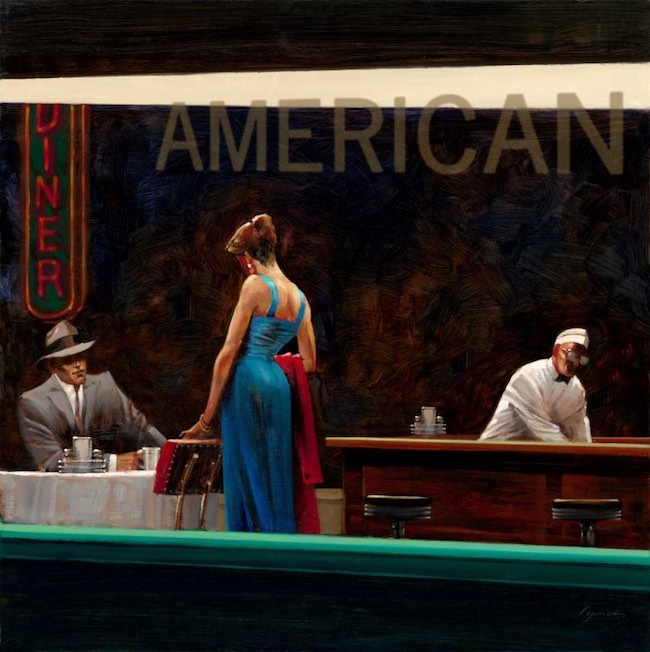

In Evening proposition al contrario, l’artista immortala uno scorcio di una normale serata in un bar il cui punto di vista pittorico è dal di fuori, esattamente come in molte opere di Edwar Hopper, come se l’osservatore fosse invitato a spiare da dietro la finestra del tempo il modo di vivere la notte di molti anni fa, e cioè in maniera serena, tranquilla, senza eccessi e con l’eccitazione del non sapere se un nuovo incontro darà finalmente concretezza alle aspettative emotive.

L’opera fa parte di un dittico e la seconda tela, intitolata Evening rendez-vous, mostra invece una coppia già costituita che si è data appuntamento, secondo quanto suggerito dal titolo, in quel luogo probabilmente per entrare più in confidenza, per consolidare una conoscenza precedentemente iniziata oppure semplicemente per trascorrere una serata fuori casa a sorseggiare un drink. Il romanticismo di Brent Lynch si sprigiona però in maniera persino più intensa nei dipinti panoramici, quelli in cui l’uomo e la donna scelgono di trascorrere una giornata all’aperto, nella rilassatezza di un momento di riposo, forse un sabato o una domenica pomeriggio in cui scegliere di avvicinarsi al mare per contemplarne la bellezza, oppure di salire sulla moto e girovagare senza meta solo per il piacere di stare insieme e sentire il vento tra i capelli che contribuisce a infondere il senso di liberà.

L’opera Costal ride narra di un momento di pausa dal viaggio, forse una richiesta da parte della donna di fermarsi a fumare una sigaretta o semplicemente a osservare il paesaggio intorno in quella posa languida e tipica della femminilità degli anni Cinquanta che non può fare a meno di incantare l’osservatore. La luce in questa tela è soffusa, quasi come se il momento immortalato appartenesse al tardo pomeriggio, quando il sole si prepara al tramonto, avvolgendo le due figure protagoniste e propagando la loro disattenzione l’uno all’altra che però suggerisce un’unione a un livello più alto, quella che si percepisce trovandosi vicino a una persona con cui l’intesa è talmente consolidata da essere tangibile anche quando entrambi sembrano distratti da altro. Questo è ciò che emerge dalle opere di Brent Lynch, quel senso di abitudine che non sconfina mai nell’insoddisfazione piuttosto evoca l’appagamento. Brent Lynch ha alle spalle una lunghissima carriera nel campo dell’arte, inizialmente come illustratore e designer con collaborazioni nell’ambito dello sport, del turismo, dell’opera, della danza e del teatro, e poi in una seconda fase sceglie di dedicarsi esclusivamente a dipingere riscuotendo consensi dal pubblico e dai collezionisti; è rappresentato dalla Galeria de Ida Victoria‘ a San Jose Del Cabo, Messico. In Canada, è rappresentato dalle Mountain Galleries a Banff, Alberta, e a Jasper, Whistler, e da The Avenue Gallery di Victoria.

BRENT LYNCH-CONTATTI

Sito web: http://brentlynch.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100063663781241

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/painterlynch/

The evocative atmospheres between music and romanticism in Brent Lynch’s American Realism

There are artists who cannot help but cast their gaze on reality, because it is precisely by starting from it that they succeed in imagining the times of a recent past whose values and sensations are purer, less disenchanted, still full of that magic of a world yet to be built, yet to be savoured, thus transforming painting into an opportunity for the observer to evoke images and settings not so distant that they cannot be recovered and relived with the same approach. Today’s protagonist chooses a strongly figurative style to which he infuses an almost rarefied appearance at times, in order to observe a reality suspended in the past, between reality and the pleasantness of life found in small, apparently ordinary habits that were nevertheless able to give a fuller meaning to existence.

Between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, began to emerge in American artists a special attention towards the working class, towards common life far removed from the aristocratic salons that had nothing interesting or stimulating about them, especially since the transformations that were emerging in the society of the time were visible in that very background society that lived, enjoyed, and reconstructed the varied characteristics of the countries of origin, American society being made up of a large number of immigrant workers. A large group of artists working between Philadelphia and New York decided to get together and create common guidelines that took shape in the Ashcan School, in fact the beginning of that American Realism that gave exceptional talents to the history of art, one of them being Edward Hopper. In this movement what emerged clearly, apart from the different interpretations of each exponent, was the cross-section of a society in the process of change, an economic class that was slowly rising, was gaining purchasing power and therefore beginning to dictate the rules of leisure, of entertainment, tuning in to a character that was certainly more popular and yet more carefree, able to enjoy to the full all that their means could offer.

George Bellows‘ city views and panoramas were a fascinated and knowledgeable glimpse of the evolutions that American cities, particularly New York, were undergoing thanks to that multitude of nationalities, of opposing cultural and lifestyle habits that mutually enriched people and filled the streets, the beaches, the places where workers could go to enjoy themselves, such as the boxing matches to which Bellows dedicated many paintings. John Sloan, on the other hand, was fascinated by the atmospheres at night, the places where people entertained themselves, the theatres, the dance halls, or the times when women went out to do their daily shopping, to meet friends, in short, he told of a serene and lively world, full of hope for the future. On the contrary, Eward Hopper, with his skill in the use of light, recounted the loneliness of man in 1950s America, the subtle melancholic line with which he implied that in the end, despite the greater economic possibilities of the middle class, happiness did not reside in economic well-being but rather was to be found in the resolution of those insecurities, of that inexplicable melancholy that could not help but emerge once the world was closed off.

The Canadian artist Brent Lynch presents a nostalgic look at the atmospheres of those mid-20th century years in which refinement, elegance and form were considered important values, in which music and dancing were expressions of the soul and also an opportunity to let oneself be transported by the magical notes in a fascinating and smoky atmosphere in which one could make encounters, discover a different world from the one of the day and be conquered by it, for a night or forever. His artworks tell of the importance of encounters, of the relevance of the couple as an ideal condition for existence, despite the phases of static, of repetitiveness that often emerge from his canvases; yet his characters do not seem to want to leave their condition because perhaps after all, in spite of everything, it is the only one in which they feel they want to be. This point of view of his is highlighted by his tendency to produce scenes in the form of diptychs, as if to imply that life can be conducted in solitude or in pairs, leaving the observer free to choose whether to look at the whole, considering the magical harmony that emanates from it, or separately where, however, one cannot help but notice the feeling that something is missing.

His painting style is strongly realist and light is used on the basis of the sensations that Brent Lynch wishes to express, lighter and softner in the settings in which he wants to bring out a greater romanticism, those atmospheres of magical sharing in which everything around the characters seems to contribute to creating the idyll that envelops the glamorous couples he likes to portray; instead, in the paintings in which he entrusts the narrative task to the charm of the night and music, then he chooses the shadows, the veils, the evocative darkness within which to lose oneself and immerse to let be carried away by the rhythm, the notes, the smoke of the bars whose glimpses he describes. The nocturnal world is perfectly represented by the jazz clubs in which he places fascinating singers, as in the painting Pearlescent Diva where the woman appears proud, self-confident but above all transported by the melodies she is called upon to interpret; the musicians are in semi-darkness as if their presence were only functional to enhance the image of the protagonist on whom Lynch focuses, the pictorial bull’s-eye, emphasising her involvement in the act perhaps most akin to her nature, that of singing.

In Evening proposition, on the contrary, the artist immortalises a glimpse of an ordinary evening in a bar whose pictorial point of view is from the outside, exactly as in many of Edwar Hopper‘s artworks, as if the observer were invited to spy from behind the window of time on the way the night was lived many years ago, that is to say in a serene, tranquil manner, without excesses and with the excitement of not knowing whether a new encounter will finally give substance to emotional expectations. The work is part of a diptych, and the second canvas, entitled Evening rendezvous, shows instead an already constituted couple who have dated, as the title suggests, in that place probably to get to know each other better, to consolidate an acquaintance that had previously begun, or simply to spend an evening out having a drink. Brent Lynch‘s romanticism, however, is even more intense in the panoramic paintings, those in which the man and woman choose to spend a day outdoors, in the relaxation of a moment of rest, perhaps on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon when they choose to get close to the sea to contemplate its beauty, or to get on their motorbikes and wander aimlessly just for the pleasure of being together and feeling the wind in their hair that helps to instil a sense of freedom. The painting Costal ride tells of a moment of pause from the journey, perhaps a request by the woman to stop and smoke a cigarette or simply to observe the landscape around her in that languid pose typical of 1950s femininity that cannot help but enchant the observer.

The light in this canvas is subdued, almost as if the moment immortalised belonged to the late afternoon, when the sun was preparing to set, enveloping the two protagonist figures and propagating their inattention to each other, which, however, suggests a union on a higher level, that which is perceived when standing close to a person with whom the understanding is so consolidated as to be tangible even when both seem distracted by something else. This is what emerges from Brent Lynch‘s work, that sense of habit that never borders on dissatisfaction rather evokes contentment. Brent Lynch has had a very long career in the arts, initially as an illustrator and designer with collaborations in the fields of sports, tourism, opera, dance and theatre, and then in a second phase he chose to devote himself exclusively to painting, gaining acclaim from the public and collectors; he is represented by Galeria de Ida Victoria‘ in San Jose Del Cabo, Mexico. In Canada, he is represented by the Mountain Galleries in Banff, Alberta, and Jasper, Whistler, and by The Avenue Gallery in Victoria.