Nell’urgenza di vivere e raccontare il momento presente, quel contemporaneo confuso e disorientante che costituisce il mondo attuale, molti artisti tendono a trascurare, tralasciare e alcune volte persino rinnegare soprattutto dal punto di vista stilistico, quel passato più lontano che però ha saputo descrivere, seppure con modalità differenti, le debolezze, le paure e i difetti dell’umanità di ieri e che a uno sguardo attento e profondo appaiono molto analoghe a quelle dell’individuo moderno. Il protagonista di oggi parte proprio da questa osservazione per lasciar emergere similitudini e per evidenziare pregi e difetti di una contemporaneità troppo spesso dimentica di tutto ciò che è già accaduto prima, per esser in grado di riconoscere gli eventi attuali.

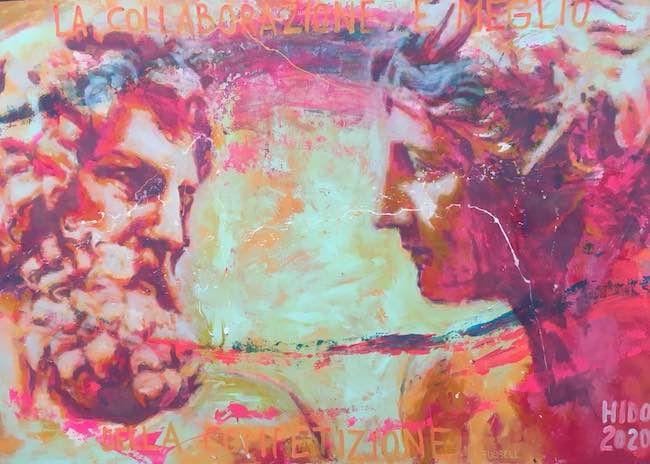

In quella rivoluzione assoluta che ha contraddistinto il Ventesimo secolo, la rottura con gli stili tradizionali e accademici a lungo acclamati come suprema forma espressiva fu netta, sovversiva al punto di rifiutare letteralmente tutta la figurazione per affermare un nuovo assioma, quello cioè che il gesto plastico, la sua essenza, non poteva essere legata solo e unicamente alla rappresentazione della realtà perché esso era ben superiore persino alla soggettività stessa dell’esecutore dell’opera. Eppure nei tempi precedenti era stata esattamente quella figurazione un elemento essenziale alla comprensione, all’erudizione del popolo, e alla diffusione di concetti e di simboli che venivano introdotti nella riproduzione di statue ed effigi. Nel Classicismo infatti i dogmi della religione, rigorosamente politeista, e i significati del mito venivano rappresentati per lanciare un monito, per spiegare l’importanza di avere un comportamento etico e consono alla morale, per proseguire verso un cammino di civiltà e di rispetto di ogni componente della società. In particolar modo nel periodo Classico della Grecia antica, agli artisti venivano commissionati decori dei templi, dei santuari o sculture in occasione di celebrazioni pubbliche, come testimoniano le meravigliose statue di Fidia visibili sul Partenone che esaltano l’eroismo e il coraggio, doti che piacevano agli dei e che, qualora fossero mancate nella quotidianità avrebbero certamente suscitato le ire degli abitanti dell’Olimpo. Altro celeberrimo maestro d’arte del secolo successivo fu Prassitele, appartenente all’inizio del periodo Ellenistico in cui la scultura cominciava a essere richiesta anche all’interno delle case nobili e di conseguenza le tematiche cominciarono ad avvicinarsi all’essere umano e ai suoi piccoli e grandi peccati. Nei periodi che seguirono il popolo romano si ispirò alla civiltà greca sia per il culto, anche in questo caso politeista, sia nella scultura proprio perché i maestri che li avevano preceduti erano stati in grado di raggiungere una perfezione esecutiva a cui attingere sia dal punto di vista della tecnica che anche da quello della capacità di utilizzare l’arte come messaggio per la gente che in quel modo apprendeva le linee guida di azioni giuste. I secoli precedenti al Novecento furono un susseguirsi e un inseguire la bellezza esattamente come narrata da Lisippo e i suoi predecessori, continuando a costituire per lungo tempo, e anche dopo l’introduzione del Cristianesimo, una rappresentazione delle tematiche religiose. L’artista ligure Samuele Di Felice, in arte Hido, trae ispirazione proprio dalle statue del periodo Classico della Grecia per riprendere e attualizzare temi ancora attuali, svelando la convinzione che sia solo osservando e mai dimenticando il passato che si possa avere maggiore coscienza del presente, perché un’umanità senza memoria è un’umanità destinata a ripetere sempre gli stessi errori.

Nelle sue opere entrano pertanto le divinità, che tanto terrorizzavano per le loro ire e intimorivano per la consapevolezza che osservassero dall’alto, divengono protagoniste di opere in cui solo l’aspetto formale è simile alle statue del passato, perché Di Felice sovverte e scardina le regole esecutive non solo scegliendo come supporto il legno bensì utilizzando materiali sperimentali attraverso cui mostra all’osservatore quanto sia possibile rendere attuale anche ciò che apparentemente è desueto, antico, appartenente a un mondo tanto lontano quanto in realtà vicino proprio perché in fondo i valori, i sentimenti e i pericoli derivanti da determinati atteggiamenti siano gli stessi, oggi come ieri.

Utilizza acrilico mescolandolo alle sabbie, al poliuterano, al cemento su cui a volte agisce con il fuoco ossidante, o con l’acido solforico o cloridrico per modificarne e intensificarne il risultato finale, e attraverso questa contemporaneizzazione delle effigi delle grandi divinità interpreta, suggerisce e apre una finestra su un messaggio, su una riflessione che l’osservatore è stimolato a compiere.

Gli dei, ancora una volta dimostrando la perpetuazione di concatenamenti di cause ed effetto che influenzano il corso degli eventi, divengono così simboli di una lettura dei tempi contemporanei caratterizzati da una distrazione, da una tendenza a rimanere sulla superficie che impedisce all’individuo di rendersi conto delle dinamiche sottili, delle forze più sotterranee che si muovono generando cambiamenti e modificazioni di cui l’uomo si rende conto solo troppo tardi. Il monito di Samuele Di Felice è pertanto quello di spingersi verso profondità diverse, di ascoltare con maggiore attenzione il senso di ciò che accade e lo fa lasciando la parola alle stesse divinità che erano state in grado di diffondere insegnamenti tanti secoli fa; anche se poi in realtà la morale che tanto pretendevano di dettare era regolarmente sovvertita dai loro comportamenti capricciosi e dissoluti.

Nell’opera Hermes e Psiche, Di Felice immortala un frangente del mito dell’anima gemella, dell’amore unico e incontrastabile in grado di superare tutte le prove, di sopravvivere anche alle difficoltà e di trovare aiuto e sostegno persino da chi non si sarebbe immaginato; nel mito infatti la giovane Psiche è l’innamorata di Eros il quale, malgrado l’opposizione della madre Afrodite, decide comunque di lottare per un’umana solo in virtù dell’amore che prova per lei facendo in modo di proteggerla attraverso le sue energie divine anche quando la più importante dea dell’Olimpo decide di mettersi contro quell’amore. Hermes rappresenta l’amicizia, la persona pronta ad aiutare con sincerità, disponibilità e a sostenere la causa degli innamorati ostacolati e di contribuire a quel lieto fine che in fondo è il sogno di ogni essere umano.

Il dono della discordia rappresenta invece la facoltà dell’uomo di entrare in competizione al punto di ricorrere a ogni mezzo e sotterfugio pur di vincere su un antagonista, dimenticando che molto spesso il risultato finale ha molto meno valore di quanto sperato o immaginato e dunque riprendendo il tema del pomo d’oro che aveva causato una lite furiosa tra le dee a cui seguì la decisione di Zeus di affidare la scelta su chi tra Era, Afrodite e Atena meritasse la mela destinata alla più bella, Samuele Di Felice mette in primo piano la futilità e la superficialità con cui si affrontano gli episodi e le cause che arrivano persino a generare le guerre. Nel caso della vicenda mitologica si trattava della guerra di Troia, ma non è forse l’arrivismo e la sete di prevaricazione che ha sempre provocato tutti i conflitti a seguire? È questa la riflessione su cui indugia l’artista, sottolineando quanto sarebbe sufficiente avere un maggiore senso della misura, della responsabilità e dell’etica per evitare conseguenze irreparabili.

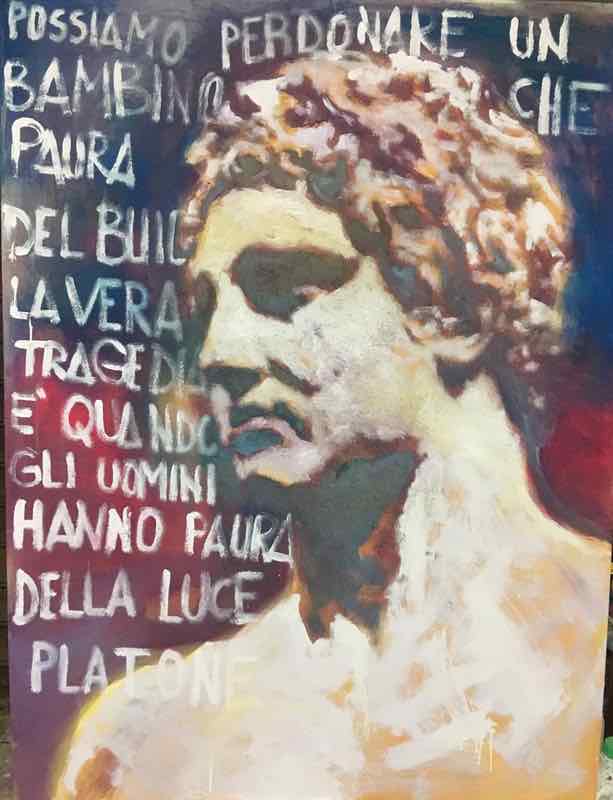

E poi l’opera Young Platone in cui Samuele Di Felice, attraverso una frase del celebre pensatore greco, mette in luce uno dei concetti più importanti, quello del condizionamento dell’uomo da parte della società, da parte delle radici in cui è cresciuto che se da un lato appaiono rassicuranti, dall’altro possono rappresentare un limite alla sete di conoscenza in grado di generare un’importante evoluzione; dunque come si legge nella frase, e come espresso nel mito della caverna di Platone, al bambino si può scusare il timore e la mancanza di termini di paragone per comprendere che il buio è solo una parte della realtà, mentre all’adulto non è concesso di continuare volutamente a tenere gli occhi chiusi solo perché tutto ciò che già si conosce fa meno paura di quanto potrebbe scoprire. L’invito dunque è quello di pensare con la propria testa, di sfuggire al condizionamento e di cercare la propria verità, nella consapevolezza che non esiste una sola e unica versione delle cose e delle circostanze bensì molte sfaccettature che aprono la meditazione e permettono all’individuo di crearsi una propria e unica idea.

Samuele Di Felice ha al suo attivo numerose mostre personali in Italia e all’estero, Ibiza, così come la partecipazione a fiere internazionali a Zagabria, Amsterdam, Parigi, Copenaghen, Lavagna, Parma, Sestri Levante, Pavia e Padova; alcune sue opere sono in esposizione permanente presso Palazzo Franzoni, sede del Comune, e presso l’Azienda Ospedaliera, entrambi di Lavagna.

SAMUELE DI FELICE-CONTATTI

Email: samuelehido@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/samuele.d.felice

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hido.art.81/

Samuele Di Felice’s reinterpretation of the Classical world, to observe dynamics and attitudes that have always belonged to mankind

In the urgency of living and recounting the present moment, that confused and disorienting contemporary that constitutes today’s world, many artists tend to overlook, neglect and sometimes even disown, especially from a stylistic point of view, that more distant past that has nevertheless been able to describe, albeit in different ways, the weaknesses, fears and defects of yesterday’s humanity and that, at a careful and profound glance, appear very similar to those of the modern individual. Today’s protagonist starts precisely from this observation to allow similarities to emerge and to highlight the merits and flaws of a contemporaneity that too often forgets all that has gone before, in order to be able to recognise current events.

In that absolute revolution that marked the 20th century, the break with the traditional and academic styles long acclaimed as the supreme form of expression was clear, subversive to the point of literally rejecting all figuration in order to affirm a new axiom, namely that the plastic gesture, its essence, could not be linked solely and exclusively to the representation of reality because it was far superior even to the subjectivity of the artwork’s executor. Yet in earlier times it was precisely that figuration that had been an essential element to the understanding, the erudition of the people, and the dissemination of concepts and symbols that were introduced in the reproduction of statues and effigies. In Classicism, in fact, the dogmas of religion, rigorously polytheistic, and the meanings of myth were represented in order to issue a warning, to explain the importance of ethical and moral behaviour, to continue towards a path of civilisation and respect for every component of society. Particularly in the Classical period of ancient Greece, artists were commissioned to decorate temples, sanctuaries or sculptures on the occasion of public celebrations, as witnessed by the marvellous statues of Phidias visible on the Parthenon extolling heroism and courage, qualities that pleased the gods and which, if they were lacking in everyday life, would certainly have aroused the wrath of the inhabitants of Olympus. Another celebrated art master of the next century was Praxiteles, who belonged to the beginning of the Hellenistic period in which sculpture began to be in demand even within noble houses and consequently the themes began to approach human beings and their small and big sins. In the periods that followed, the Roman people were inspired by the Greek civilisation both in worship, again polytheistic, and in sculpture precisely because the masters who had preceded them had been able to achieve a perfection of execution that they could draw on both in terms of technique and also in terms of their ability to use art as a message to the people who in that way learned the guidelines for right actions.

The centuries preceding the 20th century were a succession and pursuit of beauty exactly as narrated by Lysippos and his predecessors, continuing for a long time, and even after the introduction of Christianity, to represent religious themes. Ligurian artist Samuele Di Felice, a.k.a. Hido, draws inspiration precisely from the statues of the Classical period of Greece to take up and actualise themes that are still topical, revealing the conviction that it is only by observing and never forgetting the past that one can have a greater awareness of the present, because a humanity without memory is a humanity destined to always repeat the same mistakes. In his works, therefore, the divinities, who so terrified by their wrath and intimidated by the knowledge that they observed from above, become the protagonists of artworks in which only the formal aspect is similar to the statues of the past, because Di Felice subverts and disrupts the rules of execution not only by choosing wood as his support, but also by using experimental materials through which he shows the observer how it is possible to bring up to date even that which is apparently obsolete, ancient, belonging to a world as distant as it is actually close, precisely because in the end the values, feelings and dangers deriving from certain attitudes are the same, today as yesterday. He uses acrylic, mixing it with sands, polyurethane, cement on which he sometimes acts with oxidising fire, or with sulphuric or hydrochloric acid to modify and intensify the final result, and through this contemporaryisation of the effigies of the great divinities he interprets, suggests and opens a window on a message, on a reflection that the observer is stimulated to make. The gods, once again demonstrating the perpetuation of concatenations of cause and effect that influence the course of events, thus become symbols of an interpretation of contemporary times characterised by distraction, by a tendency to remain on the surface that prevents the individual from realising the subtle dynamics, the more subterranean forces that move, generating changes and modifications that man realises only too late. Samuele Di Felice’s warning is therefore to go to different depths, to listen more attentively to the meaning of what is happening, and he does so by leaving the word to the same divinities who were able to spread teachings many centuries ago; even if in reality the morals they claimed to dictate were regularly subverted by their capricious and dissolute behaviour.

In the painting Hermes and Psyche, Di Felice immortalises a juncture in the myth of the soul mate, of the unique and uncontestable love capable of overcoming all trials, of surviving even difficulties and of finding help and support even from those one would not have imagined; in the myth, in fact, the young Psyche is the lover of Eros who, despite his mother Aphrodite’s opposition, nevertheless decides to fight for a human only by virtue of the love he feels for her, making sure to protect her through his divine energies even when the most important goddess of Olympus decides to turn against that love. Hermes represents friendship, the person ready to help with sincerity, willingness and support the cause of thwarted lovers and to contribute to that happy ending that is after all the dream of every human being. The gift of discord, on the other hand, represents man’s ability to enter into competition to the point of resorting to every means and subterfuge in order to win over an antagonist, forgetting that very often the end result is much less valuable than hoped for or imagined, and thus echoing the theme of the golden apple that caused a furious quarrel between the goddesses that was followed by Zeus’ decision to entrust the choice of which of Hera, Aphrodite and Athena deserved the apple destined for the most beautiful, Samuele Di Felice brings to the fore the futility and superficiality with which episodes and causes are dealt with that even generate wars. In the case of the mythological episode, it was the Trojan War, but is it not perhaps the arrivism and thirst for prevarication that has always provoked all the conflicts to follow? This is the reflection on which the artist dwells, emphasising how it would be sufficient to have a greater sense of measure, responsibility and ethics to avoid irreparable consequences. And then there is the artwork Young Plato in which Samuele Di Felice, through a phrase from the famous Greek thinker, highlights one of the most important concepts, that of man’s conditioning by society, by the roots in which he has grown up, which, while appearing reassuring, can also represent a limit to the thirst for knowledge capable of generating an important evolution; therefore, as the sentence states and as expressed in Plato’s myth of the cave, the child can be excused for the fear and the lack of terms of comparison to understand that darkness is only a part of reality, while the adult is not allowed to deliberately continue in keeping his eyes closed just because everything he already knows is less frightening than what he might discover. The invitation is hence to think for oneself, to escape conditioning and to seek one’s own truth, in the knowledge that there is no one and only one version of things and circumstances, but rather many facets that open up meditation and allow the individual to create his own and unique idea. Samuele Di Felice has to his credit numerous solo exhibitions in Italy and abroad, Ibiza, as well as participation in international exhibitions in Zagreb, Amsterdam, Paris, Copenhagen, Lavagna, Parma, Sestri Levante, Pavia and Padua; some of his works are on permanent display at Palazzo Franzoni, the seat of the Municipality, and at the Hospital, both in Lavagna.