Lo sguardo verso un passato non molto lontano contraddistingue alcuni artisti che preferiscono rimanere legati alla figurazione e ai valori che gli anni trascorsi avevano e che nei tempi presenti sembrano quasi perduti; l’abitudine ad apparire al meglio, che era un principio irrinunciabile delle nostre nonne, non aveva nulla a che fare con la superficialità e la corsa spasmodica all’apparire della contemporaneità, bensì sottintendeva un rispetto per se stessi e per gli altri che emergeva anche dalle buone maniere, dalla grazia e dalla delicatezza con cui si usava interagire e comportarsi. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi mostra una sussurrata nostalgia nei confronti di quel tipo di atteggiamento che viene narrato con una cifra pittorica a sua volta vicina a due tra i principali stili dei primi decenni del secolo scorso che sapientemente mescola, regalando all’osservatore opere affascinanti e di forte equilibrio estetico.

Tra la fine dell’Ottocento e i primi anni del Novecento, l’Europa fu investita da un vento di ottimismo, di piacevolezza del vivere grazie al miglioramento crescente delle condizioni di vita dovuto alle innovazioni tecnologiche che si susseguivano rapidamente in quegli anni, come la scoperta dell’elettricità, la radio, le prime automobili, le scoperte mediche per debellare malattie mortali; fu proprio nel contesto di questa Belle Epoque che nacque in Francia, diffondendosi poi in tutti i principali paesi europei, l’Art Nouveau, o Modernismo, o Stile Liberty o Secessione, nomi diversi per definire il medesimo stile artistico. Le linee guida includevano l’armonia estetica, le decorazioni floreali e la diffusione dell’arte ad altri settori in precedenza creduti solo artigianali, legandosi così alle tematiche dell’appena precedente Arts and Crafts inglese; vetri decorati, gioielli, oggetti di arredamento, architettura delicata e leggera nell’aspetto finale ma frutto di un accurato lavoro esecutivo, immagini idilliache di donne in pose accattivanti e tuttavia rappresentate con l’eleganza che doveva contraddistinguere quell’epoca, adornavano palazzi, salotti e luoghi pubblici delle principali capitali europee come Parigi, Bruxelles, Vienna, Budapest, e ancora Barcellona, Monaco, solo per citarne alcune. Nel mondo strettamente pittorico due tra i maggiori rappresentanti dell’Art Nouveau furono l’austriaco Gustav Klimt e il ceco Alfons Mucha, diversi eppure entrambi incredibili interpreti di questo stile delicato e raffinato. Qualche decennio dopo, e precisamente dopo la fine della prima guerra mondiale che coinvolse l’intero vecchio continente, nella cultura e nell’arte emerse un nuovo desiderio di rivalsa nei confronti delle brutture e le atrocità del conflitto che spinse architetti, artisti, decoratori, orafi e manifatturieri a concentrarsi sul lusso, sulla sontuosità volta a sottolineare un ritrovato benessere, quello negato in precedenza, e sull’estetica. Il sentimento si trasformò in movimento artistico che prese il nome di Art Déco di cui Tamara de Lempicka fu la principale rappresentante dell’ambito pittorico, icona di coraggio, di stile, di eleganza che scaturiva dalle sue tele in cui le protagoniste, sempre donne, esprimevano da un lato l’attenzione alla forma e alla bellezza che era appunto caratteristica della corrente artistica, ma dall’altro anche un sicurezza in se stesse per la loro capacità di emanciparsi, di guadagnarsi un posto di primo piano nella nuova società ricostruita dopo il conflitto. Le pose delle sue figure femminili erano languide e incredibilmente glamour perché in fondo la cura dell’aspetto all’epoca era un sintomo di cura verso se stessi e di rispetto verso gli altri. L’artista campana Clara De Santis sceglie uno stile pittorico in cui riesce a mescolare la delicatezza e la l’armonia floreale dell’Art Nouveau, all’eleganza spesso persino ironica, alla consapevolezza in se stessi e del proprio fascino tipico invece dell’Art Déco di Tamara del Lempicka, attraverso cui sottolinea l’importanza di mantenere quei valori, quel legame con un passato troppo spesso messo all’angolo come se non fosse più utile.

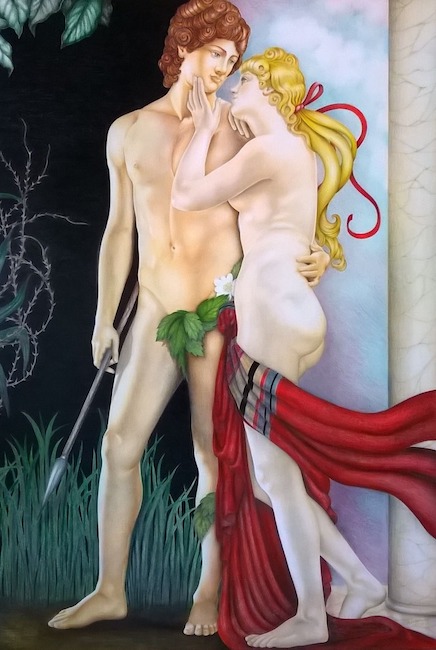

Dunque a volte si rivolge verso un Classicismo rivisitato e adattato al suo punto di vista, sottolineando quanto forte possa essere l’influenza di tutto ciò che ha costituito il percorso artistico, ma anche esistenziale, di tutto ciò che ha preceduto questo strano secolo attuale che sembra voler allontanare dalle certezze precedenti.

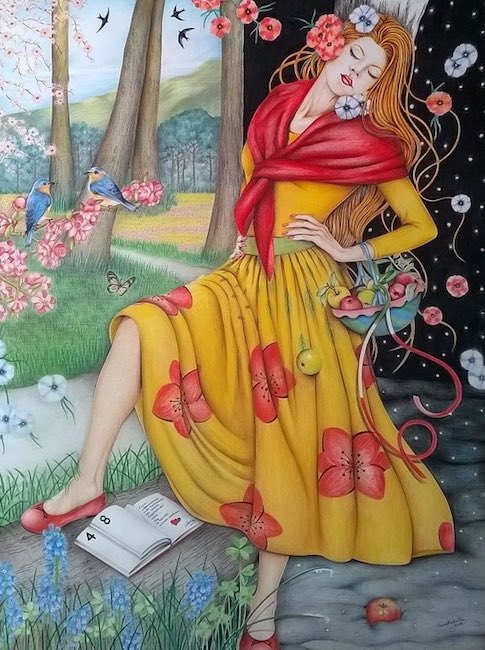

Ma il suo tratto pittorico tende naturalmente verso l’Art Déco sia nella delicatezza quasi eterea con cui descrive racconta i suoi protagonisti, nei chiaroscuri attraverso i quali sottolinea le curve dei muscoli, le ombre dei volti, la sinuosità degli abiti o dei drappi con cui avvolge i personaggi; mentre invece per quanto riguarda le pose, le movenze languide, l’atteggiamento seduttivo che però resta sempre raffinato senza sconfinare mai nella volgarità, Clara De Santis si avvicina all’Art Nouveau, anche in virtù della forte presenza della natura nelle sue opere, come se la bellezza dell’essere umano trovasse la sua maggiore esaltazione e armonia proprio in quel mondo magico e meraviglioso che lo circonda. Dunque la raffinatezza rimane dominante nelle tele di Clara De Santis, anche quando racconta di un nudo, di un momento di intimità, di un sensuale mistero, poiché non oltrepassa mai quella linea del pudore appartenente, appunto, ad altri tempi.

Questo tipo di atteggiamento da parte dell’artista emerge chiaramente nell’opera Il segreto, dove malgrado la nudità la donna protagonista nasconde pudicamente le parti intime, attraendo così ancor di più l’attenzione dell’osservatore sul suo volto e sul significato della chiave sorretta da una corda e che sembra essere un invito a scoprire la sua vera essenza piuttosto che le sue forme; il fatto che la De Santis scelga di immortalarla senza veli costituisce di fatto una metafora, un suggerimento su quanto sia necessario abbassare le difese e mostrare l’autentico modo di essere se davvero si desidera dare a qualcuno l’accesso al proprio cuore, alle profondità dell’animo che vengono difese dalle maschere indossate quotidianamente.

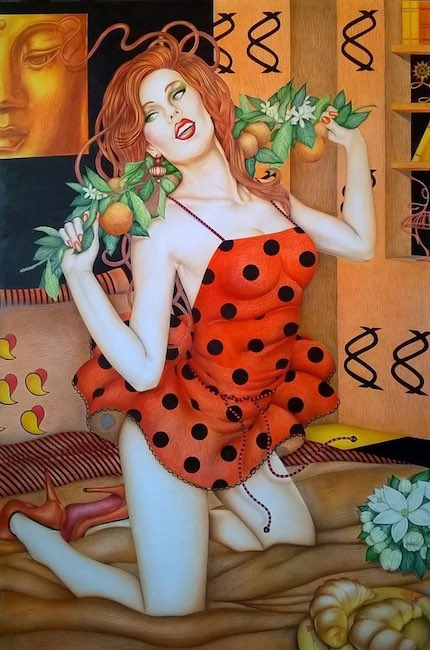

In Orange energy invece, la ragazza immortalata appare più esuberante della precedente, non ha paura di mostrare la sua allegria, la sicurezza in se stessa che la induce a mostrare con orgoglio la propria apparenza, certa di poter conquistare, in virtù della sua vitalità tutta meridionale, chiunque posi il suo sguardo su di lei; l’elemento naturale è costituito in questa tela dalle arance, simbolo della Campania, che viene utilizzato dalla donna come coadiuvante al suo gioco di seduzione ma anche come elemento affine alla sua energia vitale. Il tratto grafico più definito si accompagna alle sfumature del chiaroscuro con cui l’artista definisce delicatamente la pelle, spesso incredibilmente chiara, di tutti i suoi protagonisti, come se la luminosità del colore dovesse diventare ulteriore elemento distintivo del tratto pittorico.

E infatti una delle caratteristiche più evidenti dell’opera Uomo con cappello è proprio la luce, la chiarezza della pelle che diventa esaltazione di quei tratti efebici che Clara De Santis cerca di rendere più virili attraverso la sigaretta che pende dalle labbra del giovane, come se egli stesso fosse impaziente di oltrepassare quella fase post-adolescenziale per entrare nel mondo adulto; la posa è sapientemente seducente, come se fosse perfettamente consapevole della sua bellezza e volesse esaltarla accentuando la sensualità dello sguardo e del gesto di mettere la mano dietro la testa. Gioca con l’immaginario comune l’artista, associando quell’approccio seduttivo al fascino della divisa, da sempre attraente per le donne, come se il ragazzo fosse un giovane marines degli anni Venti approdato nel vecchio continente deciso a conquistare il cuore di qualche fanciulla.

Quasi tutte realizzate in pastello su carta, tranne qualche eccezione come Apparenza in cui la sensuale Marylin Monroe è realizzata in tecnica mista, le opere di Clara De Santis svelano la sua incredibile dote figurativa e anche nell’utilizzo del colore sapientemente sfumato e adeguato all’intenzione creativa; ma l’artista non si ferma alla rappresentazione visiva della realtà, nel suo caso immaginata attraverso uno sguardo quasi nostalgico dei tempi che furono, bensì il suo innato eclettismo la spinge a misurarsi con la moda, la musica e la poesia.

Ed è proprio con quest’ultima che accompagna alcune sue opere, come se lo sguardo non fosse sufficiente a raccontare le profondità dei concetti che desidera esprimere, e dunque non può fare a meno di ricorrere a un ulteriore mezzo espressivo, la parola; Clara de Santis ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive e a importanti fiere del settore e le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private, di musei, e sono inserite in cataloghi e pubblicazioni d’arte.

CLARA DE SANTIS-CONTATTI

Email: claramode@inwind.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/artedesantis

https://www.facebook.com/clara.desantis.376

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/clara.desantis.chicart/

The bridge between Art Deco and Art Nouveau in the elegant and refined style of Clara De Santis

A glance towards a not too distant past distinguishes some artists who prefer to remain tied to the figuration and values that past years had and that in present times seem almost lost; the habit of looking one’s best, which was an inalienable principle of our grandmothers, had nothing to do with the superficiality and spasmodic race to appear of the contemporary world, but implied a respect for oneself and for others that also emerged from good manners, grace and delicacy with which one used to interact and behave. The artist I am going to tell you about today shows a whispered nostalgia for that kind of attitude, which is narrated with a pictorial style that is in turn close to two of the main styles of the first decades of the last century, which she skilfully mixes, giving the observer fascinating artworks with a strong aesthetic balance.

Between the end of the 19th and the early years of the 20th century, Europe was swept by a wind of optimism, of a pleasantness of life thanks to the increasing improvement in living conditions due to the technological innovations that were rapidly taking place in those years, such as the discovery of electricity, the radio, the first automobiles, and medical discoveries to eradicate deadly diseases; it was in the context of this Belle Epoque that Art Nouveau, or Modernism, or Stile Liberty or Secession, different names for the same artistic style, was born in France, later spreading to all major European countries. The guidelines included aesthetic harmony, floral decoration and the diffusion of art to other areas previously thought to be only craft, thus linking up with the themes of the just preceding English Arts and Crafts; decorated glassware, jewellery, furnishings, architecture that was delicate and light in its final appearance but the result of painstaking workmanship, idyllic images of women in captivating poses and yet represented with the elegance that was to characterise that era, adorned palaces, drawing rooms and public places in the major European capitals such as Paris, Brussels, Vienna, Budapest, Barcelona and Munich, to name but a few. In the strictly pictorial world, two of the greatest representatives of Art Nouveau were the Austrian Gustav Klimt and the Czech Alfons Mucha, different yet both incredible interpreters of this delicate and refined style. A few decades later, precisely after the end of the First World War, which involved the entire old continent, a new desire for revenge against the ugliness and atrocities of the conflict emerged in culture and art, prompting architects, artists, decorators, goldsmiths and manufacturers to focus on luxury, on sumptuousness aimed at emphasising a newfound prosperity, the one denied before, and on aesthetics.

The sentiment was transformed into an artistic movement that took the name Art Deco, of which Tamara de Lempicka was the main representative in the pictorial sphere, an icon of courage, style and elegance that emanated from her canvases in which the protagonists, always women, expressed on the one hand the attention to form and beauty that was characteristic of the artistic current, but on the other hand also a self-confidence in their ability to emancipate themselves, to earn a prominent place in the new society rebuilt after the conflict. The poses of her female figures were languid and incredibly glamorous because, after all, care for one’s appearance at the time was a symptom of self-care and respect for others. The Campania-born artist Clara De Santis chooses a painting style in which she manages to mix the delicacy and floral harmony of Art Nouveau with the often even ironic elegance, the self-awareness and self-glamour typical of Tamara del Lempicka‘s Art Deco, through which she emphasises the importance of maintaining those values, that link with a past that is too often cornered as if it were no longer useful. So at times she turns towards a revisited Classicism adapted to her point of view, emphasising how strong the influence of all that has constituted the artistic, but also existential, path of all that has preceded this strange current century that seems to want to distance itself from previous certainties. But her pictorial trait naturally tends towards Art Deco, both in the almost ethereal delicacy with which she describes her protagonists, in the chiaroscuros through which she emphasises the curves of the muscles, the shadows of the faces, the sinuosity of the clothes or the drapes with which she envelops the characters; while as regards the poses, the languid movements, the seductive attitude that nevertheless always remains refined without ever trespassing into vulgarity, Clara De Santis approaches Art Nouveau, also by virtue of the strong presence of nature in her works, as if the beauty of the human being found its greatest exaltation and harmony precisely in that magical and marvellous world that surrounds him.

Thus, refinement remains dominant in Clara De Santis‘ paintings, even when she depicts a nude, a moment of intimacy, a sensual mystery, as she never crosses that line of modesty belonging, precisely, to other times. This kind of attitude on the part of the artist clearly emerges in the artwork The Secret, where despite her nudity, the woman protagonist demurely conceals her intimate parts, thus drawing the observer’s attention even more to her face and to the significance of the key held up by a rope, which seems to be an invitation to discover her true essence rather than her forms; the fact that De Santis chooses to immortalise her without veils is in fact a metaphor, a suggestion of how necessary it is to lower one’s defences and show one’s authentic way of being if one really wants to give someone access to his heart, to the depths of the soul that are defended by the masks worn daily. In Orange energy, on the other hand, the girl immortalised appears more exuberant than the previous one, she is not afraid to show her cheerfulness, the self-confidence that leads her to proudly display her appearance, certain that she can conquer, by virtue of her all-Southern vitality, whoever casts their gaze upon her; the natural element in this canvas is oranges, the symbol of Campania, which is used by the woman as an aid to her game of seduction but also as an element akin to her vital energy. The more defined graphic line is accompanied by the nuances of chiaroscuro with which the artist delicately defines the skin, often incredibly pale, of all her protagonists, as if the luminosity of the colour were to become a further distinguishing element of the pictorial line.

And in fact, one of the most evident characteristics of the artwork Man with Hat is precisely the light, the clarity of the skin that becomes an exaltation of those ephebic features that Clara De Santis tries to make more virile through the cigarette hanging from the young man’s lips, as if he himself were impatient to move beyond that post-adolescent phase and enter the adult world; the pose is skilfully seductive, as if he were perfectly aware of his beauty and wanted to enhance it by accentuating the sensuality of his gaze and the gesture of putting his hand behind his head. The artist plays with the common imagination, associating that seductive approach with the charm of the uniform, which has always been attractive to women, as if the boy were a young marine from the 1920s who had landed on the old continent determined to win the heart of some young girl. Almost all painted in pastel on paper, with a few exceptions such as Apparenza in which the sensual Marylin Monroe is painted in mixed media, Clara De Santis‘ artworks reveal her incredible figurative talent and also in her use of colour, skilfully shaded and adapted to the creative intention; but the artist does not stop at the visual representation of reality, in her case imagined through an almost nostalgic glance at times gone by; rather, her innate eclecticism drives her to measure herself against fashion, music and poetry. And it is precisely with the latter that she accompanies some of her artworks, as if the gaze were not enough to tell the depths of the concepts she wishes to express, and therefore she cannot do without resorting to a further expressive medium, the word. Clara de Santis has to her credit the participation in many group exhibitions and important trade fairs, and her artworks are part of private collections, museums, and are included in art catalogues and publications.