Spesso il viaggio di approfondimento verso se stessi e la propria capacità di andare oltre il luogo comune per scoprire in prima persona verità appartenenti alla vita delle persone di paesi lontani e raccontati abitualmente in maniera poco completa, diviene la linea narrativa di quegli artisti che hanno bisogno di mettere tutto in discussione, intraprendendo un cammino di esplorazione del mondo in virtù del quale possono sperimentare anche la propria capacità empatica e di comprensione del di fuori da sé. In questo tipo di concetto creativo la scelta stilistica si lega prevalentemente alla figurazione proprio perché lo sguardo ha bisogno di cogliere, e di manifestare, tutto ciò che in quel momento cattura l’attenzione dell’autore, allo stesso modo in cui l’obiettivo di una macchina fotografica immortalerebbe quel fermo immagine pieno di emozione da cui è impossibile staccarsi. La pittrice di cui vi racconterò oggi appartiene a quella categoria di artisti che hanno bisogno di esplorare e lasciarsi incantare da tutto ciò che è legato a un mondo lontano, esotico e tutto da scoprire, cogliendone la realtà più autentica.

La possibilità di uscire dai confini della propria nazione e di quelle conoscenze limitate al luogo in cui si era nati e cresciuti, subì una forte accelerazione nel momento in cui la tecnologia e il progresso cominciarono a consentire alle persone di diminuire il tempo di percorrenza sia via nave che via terra, ma anche di accedere agli spostamenti a costi più accessibili; in quel contesto storico gli artisti ebbero l’occasione di andare a esplorare tutti quei mondi fino a poco prima sconosciuti, portando testimonianza nelle loro opere di quanto osservato. L’Orientalismo cominciò così a diffondersi modificando il gusto della società dell’epoca e ripercuotendosi anche nella produzione pittorica di quegli autori che ebbero l’opportunità di intraprendere dei viaggi alla scoperta di mondi esotici e pieni di fascino; Eugène Delacroix immise nei suoi dipinti le esperienze e la bellezza delle spedizioni effettuate in Marocco, paese che immortalò nella sua spontaneità e tradizionalità nel vivere quotidiano. Sempre nella prima metà dell’Ottocento l’autore scozzese David Roberts intraprese diversi viaggi alla scoperta di luoghi affacciati sul Mediterraneo, come Tangeri, che poi sfociarono nel suo desiderio di approfondire la cultura nordafricana trasferendosi a lungo in Egitto, luogo a cui dedicò moltissime tele.

Nella seconda metà del Diciannovesimo secolo la Compagnia delle Indie olandese, importando molti reperti orientali, fece sì che si diffondesse tra gli artisti il Giapponismo, influenza stilistica in cui venivano riprodotte stampe o elementi giapponesi all’interno delle opere, come nel caso dei dipinti di Vincent Van Gogh e di Claude Monet. Ma anche l’Art Nouveau si ispirò ai motivi naturalistici ukiyo-e e alla presenza predominante della figura femminile, nelle opere dei suoi maggiori esponenti come Alfons Mucha e Gustav Klimt. Qualche anno dopo fu invece il Primitivismo a trovare maggiore spazio nell’arte degli avanguardisti come Pablo Picasso, che riproduceva nel suo Cubismo volti stilizzati simili a quelli delle maschere africane, come Amedeo Modigliani che trasse ispirazione dalle stesse iconografie per raffigurare le sue algide donne con i colli lunghi, e Paul Gauguin che scelse di dedicare tutta la sua produzione artistica della maturità alla narrazione del mondo polinesiano immortalando scene di vita quotidiana, la semplicità con cui gli indigeni del luogo trascorrevano le loro giornate e la purezza di un’emozionalità che non conosceva secondi fini o ipocrisie.

Tanto fu affascinato da quell’universo lontano dall’Europa da decidere di trasferirsi lì in maniera definitiva. L’artista ceca Dagmar Buchtová appartiene alla stessa categoria di creativi che non possono scindere la pittura dal viaggio, come se attraverso la conoscenza di tutto ciò che è diverso e lontano da sé potesse scoprire aspetti e sfaccettature della propria anima e della propria essenza che emergono solo nel momento in cui si mette in relazione con culture lontane, distanti dalla propria ma proprio per questo costante fonte di arricchimento. Dopo aver rinunciato a dipingere per moltissimi anni, lei che aveva iniziato da bambina, e dopo aver cresciuto quattro figli dedicandosi al lavoro e alla famiglia, decide di riprendere in mano i pennelli frequentando una scuola a Liberec, la sua città, riscoprendo così un legame imprescindibile con l’espressione artistica rimasta solo latente e che ha trovato realizzazione nell’associazione con l’altra sua grande passione, i viaggi.

Il suo Realismo si arricchisce di tonalità intense tanto quanto lo sono gli scorci che catturano la sua attenzione, mentre la narrazione si allontana dagli abituali percorsi turistici per andare a cercare l’autenticità, l’essenza e le tradizioni vere dei luoghi che visita, gli scorci sonnecchianti il cui il tempo si ferma e il procedere della vita mostra ritmi completamente diversi da quelli europei e occidentali.

Ciò che affascina Dagmar Buchtová è svelare a se stessa, e di conseguenza all’osservatore delle sue opere, quelle piccole abitudini, quell’ordinarietà che non viene mai raccontata, tutte quelle sfaccettature di normalità nascoste dietro giudizi categorici basati sui parametri di chi li pronuncia senza soffermarsi a considerare punti di vista diversi, opposti ma non meno veri o rilevanti.

L’Espressionismo emerge proprio da questa sensibilità, da questa capacità dell’autrice di far affiorare la bellezza, la spontaneità e le abitudini radicate di paesi pieni di storia e di fascino, che di solito sono invece narrate in modo fazioso e discostato da ciò che invece sperimenta chi li visita in maniera aperta e priva di pregiudizi; dunque le tonalità intense e quasi irreali si legano imprescindibilmente al sentire di Dagmar Buchtová, alle emozioni che emergono ogni qualvolta la sua interiorità entra in contatto con un inconosciuto tutto da scoprire, da svelare a se stessa analizzandone a fondo l’essenza, le molteplicità da cui riesce a farsi una sua propria opinione che desidera raccontare attraverso i suoi dipinti.

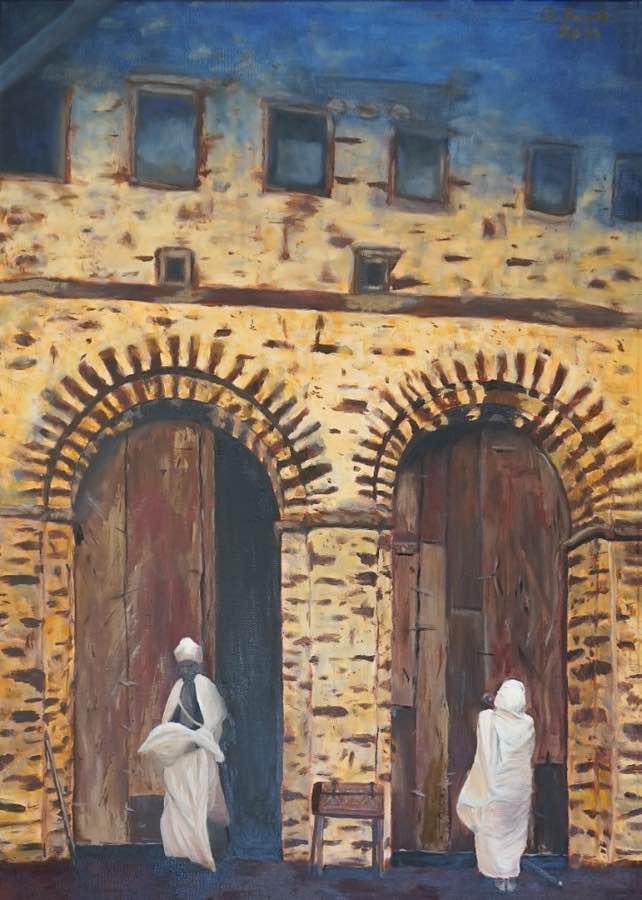

In Church Debre, Birhan Selassie, Ethiopia viene raccontato un fermo immagine legato alla storia millenaria della chiesa cristiana ortodossa, tra le più antiche chiese legate alla tradizione copta ma con specificità proprie in cui si conservano riti e manoscritti millenari; l’autrice immortala l’istante durante il quale un uomo esce e una donna entra, quasi a sottolineare la centralità del ruolo femminile assolutamente in equilibrio con quello maschile, quasi come fossero due facce della stessa medaglia. Pur essendo nota per i suoi straordinari affreschi che ricoprono quasi ogni superficie interna raffiguranti scene bibliche e angeli, costituendo un importante sito religioso, Dagmar Buchtová sceglie di dipingerne solo l’esterno, esaltando così non la magnificenza bensì la semplicità di un edificio che prima di tutto è un luogo di culto, importantissimo per gli abitanti del luogo, e di cui solo in un secondo momento può essere considerata la preziosità artistica e materiale. La rarefazione del cielo in alto, quasi coprisse i dettagli superiori del palazzo, sembra tendere verso il cielo, ascendere verso la spiritualità di quel luogo.

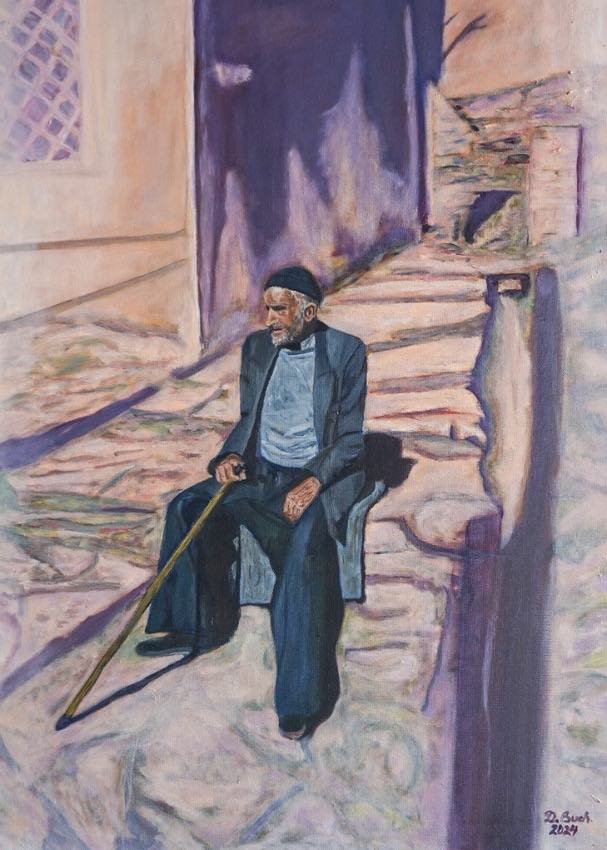

Rest Abjáne, Iran cattura invece la tranquillità di quello che viene definito il villaggio rosso, Abyaneh, che si materializza davanti allo sguardo di Dagmar Buchtová nella persona dell’anziano seduto sui gradini di accesso a una casa, probabilmente la sua, e che non ha problemi, nonostante il bastone, a pensare di rialzarsi da quella posizione. Lo sguardo dell’autrice è carezzevole nei confronti del protagonista, come se in quell’immagine volesse ritrovare tutti i nonni, la saggezza di persone depositarie di storie, di tradizioni, di aneddoti che solo attraverso i loro racconti è possibile preservare dal passare del tempo. L’età matura, sembra sottolineare la Buchtová, appiattisce le divisioni e le diversità, modera le ostilità dovute a inutili confini e contrapposizioni e rende ogni anziano un tesoro prezioso, a qualsiasi etnia o popolazione appartenga.

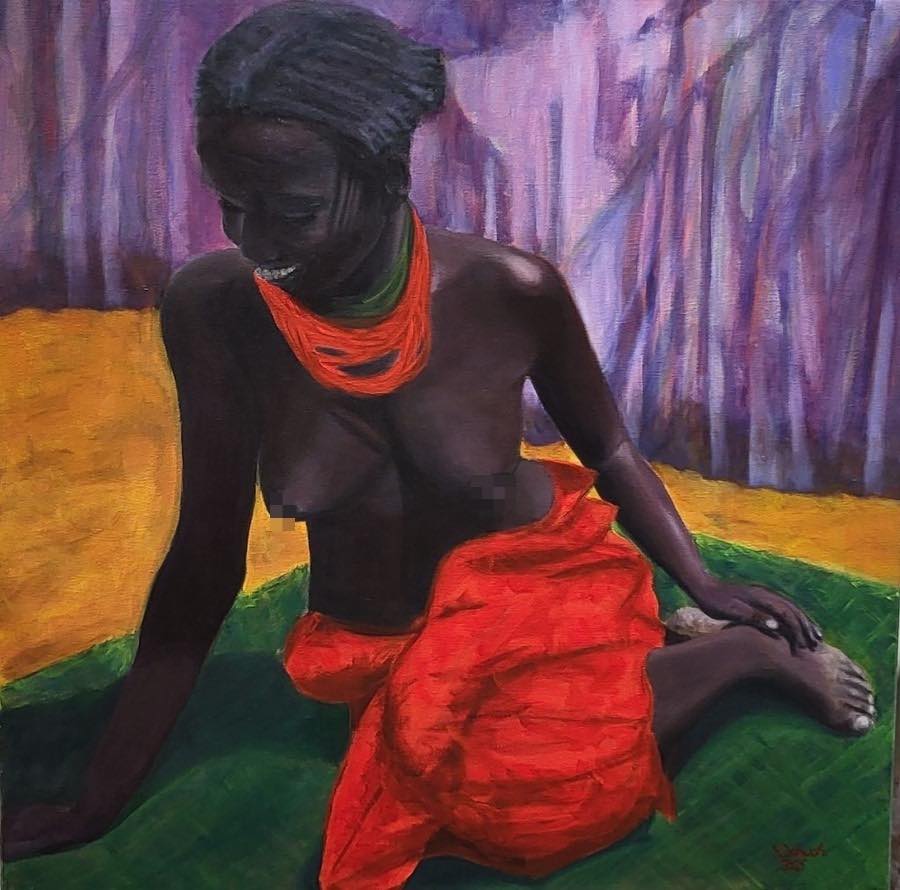

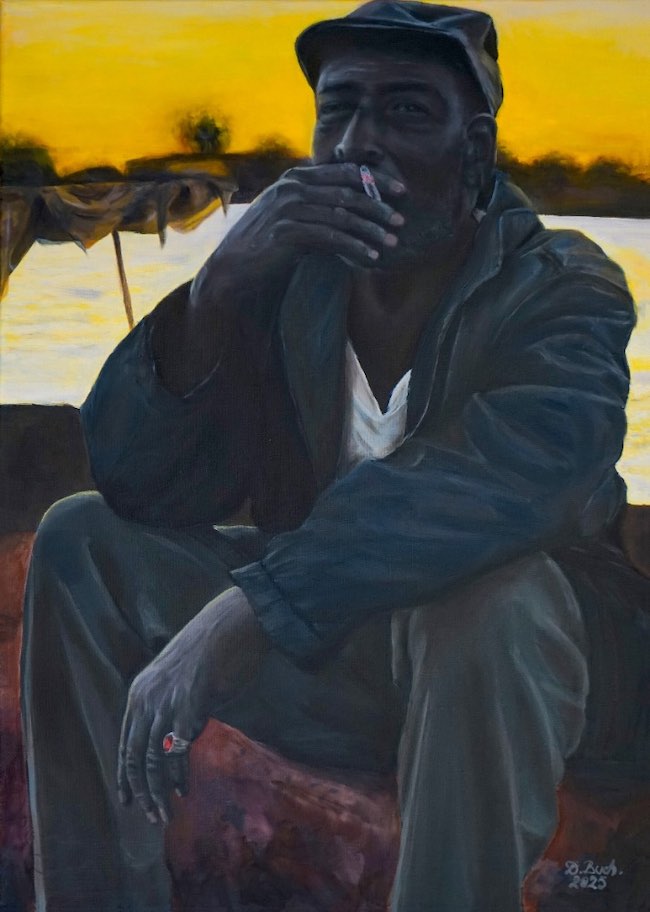

Il dipinto The man with the ring by the Gambia river, Gambia, mostra la serenità con cui in quella parte del mondo, l’Africa, gli individui affrontano le loro giornate, soprattutto quando lontani dalle grandi città, senza stress, senza correre dietro alle cose da fare e senza inseguire obiettivi effimeri che non riescono mai a dare la felicità, a far sentire l’uomo moderno davvero appagato. Il protagonista invece appare perfettamente a proprio agio, tranquillo in quel sonnacchioso pomeriggio in cui Dagmar Buchtová ha incrociato il suo sguardo scorgendone la presenza e rimanendo conquistata dall’atteggiamento naturale e spontaneo al punto di volerlo immortalare; il titolo si lega alla caratteristica che lo contraddistingue, quell’anello di valore che sembra sussurrare all’osservatore che anche senza l’atteggiamento arrivista e accumulatore tipico delle civiltà occidentali, si può comunque possedere un oggetto prezioso, probabilmente un cimelio di famiglia tramandato di padre in figlio. E l’espressione dell’uomo sembra proprio voler comunicare all’autrice quella pacatezza serena e rilassata che contraddistingue le sue giornate e la sua vita; in questo dipinto la parte espressionista si manifesta nel cielo, giallo e pieno di atmosfera, quasi fosse un’esaltazione della calma della scena.

Dagmar Buchtová ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre collettive e personali nella Repubblica Ceca, a Cipro e in Italia, tutti eventi dove ha raccolto il consenso di pubblico e di addetti ai lavori.

DAGMAR BUCHTOVÁ-CONTATTI

Email: dasa.buchtova@seznam.cz

Sito web: www.dagmarbuchtova.art/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/dasa.buchtova.9

Instagram: www.instagram.com/dasa.buchtova/

Suspended time and glimpses of the charm of distant countries in Dagmar Buchtová’s Expressionist Realism

Often, the journey of self-discovery and the ability to go beyond clichés to discover firsthand truths about the lives of people in distant countries, which are usually recounted in an incomplete manner, becomes the narrative thread of those artists who need to question everything, embarking on a travel of exploration of the world through which they can also test their capacity for empathy and understanding of the outside of themselves. In this type of creative concept, the stylistic choice is mainly linked to figuration, precisely because the gaze needs to capture and express everything that catches the author’s attention at that moment, in the same way that a camera lens would immortalize that freeze frame full of emotion from which it is impossible to detach. The painter I am going to tell you about today belongs to that category of artists who need to explore and be enchanted by everything related to a distant, exotic world waiting to be discovered, capturing its most authentic reality.

The possibility of leaving the confines of one’s own country and the limited knowledge of the place where one was born, raised accelerated rapidly when technology and progress began to allow people to reduce travel time both by sea and by land, but also to access travel at more affordable costs; in that historical context, artists had the opportunity to explore all those worlds that had been unknown until recently, bearing witness to what they observed in their works. Orientalism thus began to spread, changing the tastes of society at the time and also influencing the paintings of those artists who had the opportunity to embark on journeys to discover exotic and fascinating worlds; Eugène Delacroix incorporated the experiences and beauty of his expeditions to Morocco into his paintings, immortalizing the spontaneity and tradition of everyday life in that country. Also in the first half of the nineteenth century, the Scottish author David Roberts undertook several journeys to discover places overlooking the Mediterranean, such as Tangier, which then resulted in his desire to delve deeper into North African culture by moving for a long time to Egypt, a place to which he dedicated many canvases.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Dutch East India Company imported many oriental artifacts, leading among the artists to the spread of Japonism, a stylistic influence in which Japanese prints or elements were reproduced within artworks, as in the case of paintings by Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet. But also Art Nouveau was inspired by naturalistic ukiyo-e motifs and the predominant presence of the female figure in the works of its leading exponents, such as Alfons Mucha and Gustav Klimt. A few years later, Primitivism found greater space in the art of avant-garde artists such as Pablo Picasso, who reproduced in his Cubism stylized faces similar to those of African masks, Amedeo Modigliani, who drew inspiration from the same iconography to depict his icy women with long necks, and Paul Gauguin, who chose to devote his entire mature artistic production to narrating the Polynesian world, immortalizing scenes of everyday life, the simplicity with which the local indigenous people spent their days, and the purity of an emotionality that knew no ulterior motives or hypocrisy. He was so fascinated by that universe far from Europe that he decided to move there permanently. Czech artist Dagmar Buchtová belongs to the same category of creatives who cannot separate painting from travel, as if through the knowledge of everything that is different and distant from herself she could discover aspects and facets of her own soul and essence that emerge only when she relates to distant cultures, far from hers but precisely for this reason a constant source of enrichment. After giving up painting for many years, having started as a child, and after raising four children and devoting herself to work and family, she decided to pick up her brushes again by attending a school in Liberec, her hometown, thus rediscovering an essential link with artistic expression that had remained latent and found fulfillment in association with her other great passion, travel.

Her Realism is enriched with intense tones as much as the foreshortenings that capture her attention, while the narrative moves away from the usual tourist routes to look for the authenticity, the essence and the true traditions of the places she visits, the dozing glimpses where time stops and the progress of life shows rhythms completely different from those of Europe and the West. What fascinates Dagmar Buchtová is revealing to herself, and consequently to the observer of her works, those little habits, that ordinariness that is never talked about, all those facets of normality hidden behind categorical judgments based on the parameters of those who pronounce them without pausing to consider different, opposing but no less true or relevant points of view. Expressionism emerges precisely from this sensitivity, from the artist’s ability to bring out the beauty, spontaneity, and deep-rooted habits of countries full of history and charm, which are usually narrated in a biased way, far removed from the experiences of those who visit them with an open mind and without prejudice; thus, the intense and almost unreal tones are inextricably linked to Dagmar Buchtová‘s feelings, to the emotions that emerge whenever her inner self comes into contact with something unknown, waiting to be discovered and revealed to herself by thoroughly analyzing its essence and multiplicity, from which she is able to form her own opinion that she wishes to convey through her paintings.

In Church Debre, Birhan Selassie, Ethiopia, is captured a snapshot of the millennial history of the Orthodox Christian Church, one of the oldest churches linked to the Coptic tradition but with its own specific characteristics, where are preserved ancient rites and manuscripts; the author immortalizes the moment when a man leaves and a woman enters, as if to emphasize the centrality of the female role, in perfect balance with the male one, almost as if they were two sides of the same coin. Although it is known for its extraordinary frescoes covering almost every interior surface depicting biblical scenes and angels, constituting an important religious site, Dagmar Buchtová chooses to paint only the exterior, thus highlighting not the magnificence but the simplicity of a building that is first and foremost a place of worship, extremely important for the local inhabitants, and whose artistic and material value can only be considered secondarily. The rarefaction of the sky above, almost covering the upper details of the building, seems to tend towards the sky, ascending towards the spirituality of that place. Rest Abjáne, Iran captures the tranquility of what is known as the red village, Abyaneh, which materializes before Dagmar Buchtová‘s gaze in the form of an elderly man sitting on the steps leading up to a house, probably his own, who, despite his cane, has no trouble thinking about getting up from that position.

The author’s gaze is caressing towards the protagonist, as if in that image she wanted to find all the grandparents, the wisdom of people who are custodians of stories, traditions, anecdotes that only through their stories can it be preserved from the passage of time. Mature age, Buchtová seems to underline, flattens divisions and differences, moderates hostilities due to unnecessary boundaries and contrasts, and makes every elderly person a precious treasure, whatever ethnicity or population they belong to. The painting The Man with the Ring by the Gambia River, Gambia, shows the serenity with which individuals in that part of the world, Africa, face their days, especially when far from the big cities, without stress, without rushing around to get things done and without chasing ephemeral goals that never manage to bring happiness or make modern man feel truly fulfilled.

The protagonist, on the other hand, appears perfectly at ease, calm on that sleepy afternoon when Dagmar Buchtová caught his eye, noticing his presence and being captivated by his natural and spontaneous attitude to the point of wanting to immortalize him; the title refers to his distinguishing feature, that valuable ring that seems to whisper to the observer that even without the careerist and accumulator attitude typical of Western civilizations, one can still possess a precious object, probably a family heirloom handed down from father to son. The man’s expression seems to communicate to the artist the serene and relaxed calm that characterizes his days and his life; in this painting, the expressionist aspect is manifested in the sky, yellow and full of atmosphere, as if to enhance the calm of the scene. Dagmar Buchtová has participated in group and solo exhibitions in the Czech Republic, Cyprus, and Italy, all events where she has won the approval of the public and professionals alike.