Nella realtà contemporanea diviene difficile rimanere fermi sulle idee e sulle considerazioni, proprio perché i tempi in perpetua mutazione e le evoluzioni che inevitabilmente se ne generano impediscono all’individuo di avere dei punti fermi ben definiti; dal punto di vista artistico questa sensazione si può tradurre da un lato con l’esigenza di allontanarsi dalla realtà per evidenziare la necessità di osservare ogni cosa da un punto di vista meno influenzato dalla distrazione dell’estetica, dall’altro ponendo l’accento sulla sovrapposizione e sul fluttuare del flusso energetico che scorre al di sotto del quotidiano e che non può fare a meno di essere percepito. La protagonista di oggi trasforma e mescola le caratteristiche di molte sfaccettature interpretative dell’Arte Astratta per dar vita a uno stile ipnotico e pieno di vivacità cromatica.

Gli inizi del Ventesimo secolo coincisero con un emergente bisogno di dimostrare quanto l’arte fosse diversa e quanto potesse essere considerata tale pur distaccandosi dalla realtà osservata, dalla riproduzione delle immagini a cui lo sguardo era abituato nella quotidianità; sperimentare e ideare movimenti che mostrassero quanto il gesto plastico e la mancanza di forma riconducibile al reale potessero essere indipendenti e sufficienti a se stessi al punto di rinunciare persino alla soggettività dell’esecutore dell’opera, furono i punti fermi di tutte le differenti declinazioni dell’Arte Astratta. Laddove l’Astrattismo Lirico di Vassily Kandinsky si impose di mantenere un legame con l’interiorità attraverso il fluttuare di forme e tonalità che si armonizzavano alle sensazioni provate dall’autore durante l’ascolto della musica classica, il Suprematismo scelse invece un aspetto più geometrico, la riduzione della scala cromatica ai soli colori primari, pur mantenendo una sensazione di instabilità delle forme, una disposizione che includeva ancora un senso di movimento. Movimento che fu poi completamente ripudiato dalla rigorosità espressiva del De Stijl dove le uniche forme geometriche accettate dai fondatori della corrente, Piet Mondrian e Theo van Doesburg, erano il rettangolo, il quadrato e le linee rette. Per loro ciò che contava infatti era affermare la superiorità della perfezione plastica nella sua asetticità esaltata dai soli colori primari, senza subire alcuna influenza da parte dell’ambiente esterno, né da parte di quel mondo di sensazioni ed emozioni che nel complesso periodo a cavallo tra le due guerre mondiali per molti artisti era meglio non considerare. Tuttavia fu proprio quel rigore a rendere ben preso il De Stijl troppo lontano dal coinvolgimento e soprattutto troppo poco aperto alle variazioni che ne avrebbero consentito la prosecuzione nel corso del tempo, cosa che invece avvenne grazie alla nascita dell’Astrattismo Geometrico dove la gamma cromatica venne notevolmente ampliata introducendo un inedito possibilismo, così come cominciarono a essere accettate le forme considerate impure da Mondrian come il cerchio, le diagonali, i rombi, gli esagoni, tutto ciò che in precedenza era assolutamente rifiutato. Le trasparenze e le sovrapposizioni cominciavano a infondere nell’osservatore un senso emozionale, peraltro evocato anche dal più geometrico degli appartenenti al gruppo Der Blaue Reiter, Paul Klee che fu forse il primo a legare la geometricità al sentire dell’esecutore dell’opera. Non solo, qualche decennio, dopo, intorno agli anni Cinquanta del Novecento, alcuni esponenti dell’Espressionismo Astratto utilizzarono il Tachisme come suddivisione geometrica della tela in diverse tonalità solari e coinvolgenti in grado di suscitare nell’osservatore sentimenti positivi e comunicando la personalità narrativa dell’artista. Il riferimento è ad Hans Hoffman, grande protagonista della pittura mondiale che riuscì a introdurre la geometricità all’interno dell’emozione, appartenendo a un movimento che ripudiava qualsiasi rigore espressivo che non comprendesse il desiderio di travolgere e coinvolgere l’osservatore.

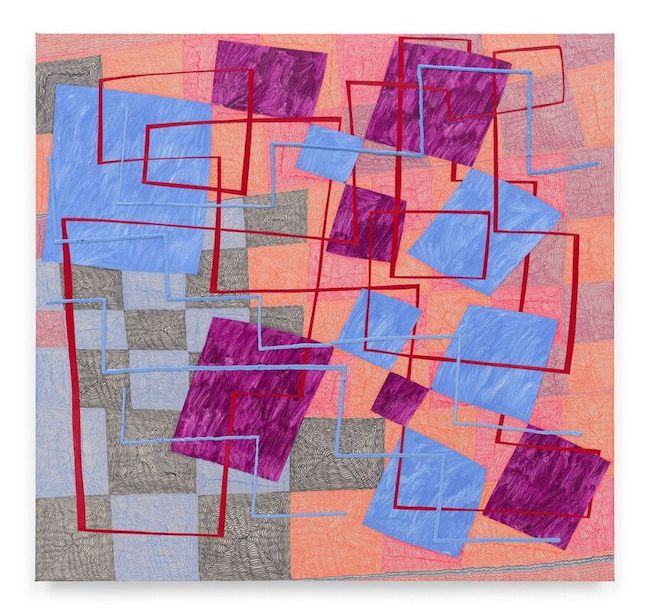

L’artista statunitense Trudy Benson evolve e rivoluziona le tracce lasciate nel passato dai suoi predecessori per elaborare uno stile in cui il colore vivace e divertente, attingendo dunque all’eredità cromatica di Hoffman, crea dei riquadri che sembrano muoversi sulla tela, sovrapponendosi e al contempo rimanendo legati tra loro, come se in qualche modo volesse enfatizzare l’interconnessione che appartiene alla realtà contemporanea senza però metterne in evidenza l’accezione negativa, piuttosto accettando questo dato di fatto e trasformandolo in senso di comunità, pur con accezione diversa dalla concezione del passato. In altre tele invece rinuncia alla geometricità per mettere l’accento, ricollegandosi così alle forme in movimento di Vassily Kandinsky, sulla fluidità, sul costante fluttuare di una realtà talmente inafferrabile da necessitare astrarsi da essa, guardarsi dentro e ascoltare solo il ritmo dei propri pensieri e delle proprie emozioni.

Anche in questa seconda serie di opere, più morbide, appare la costante del reticolo di interconnessione, quasi Trudy Benson volesse enfatizzare proprio quanto all’interno di una quotidianità mobile e inafferrabile l’unico scoglio a cui aggrapparsi sia costituito dai legami familiari, emotivi, relazionali, insomma tutto ciò che ricorda a ciascun individuo quanto può contare per le persone che fanno parte di quella rete. Da un altro punto di vista tuttavia, è impossibile non notare il riferimento ai meccanismi elettrici, a quei circuiti che sono alla base in fondo di tutta la modernità, di tutto ciò che appartiene persino a quell’oggetto ormai irrinunciabile che risponde al nome di computer e che è diventato indispensabile nella vita quotidiana.

Qui dunque emerge una diversa interpretazione delle opere di Trudy Benson, perché in questo caso il reticolo diviene un automatismo, qualcosa di funzionale al progresso a cui sembra impossibile poter rinunciare, quasi esso intrappolasse chi lo ha creato e poi eseguito. Eppure, anche con questa seconda considerazione la gamma cromatica lascia intuire l’approccio alla vita dell’autrice, quello che la induce a guardare sempre il bicchiere mezzo pieno sottolineando la capacità umana di adattarsi alle situazioni, ai cambiamenti, alle stratificazioni di esperienze e di circostanze che inevitabilmente modificano la realtà e a cui non si può che lasciarsi andare perché resistere costituirebbe una fonte di frustrazione e di impiego di energie non più funzionale all’evoluzione dell’individuo.

Anche nell’opera Chaos, considerando quanto l’imprevisto possa generare fonte di stress per la maggior parte delle persone che vedono la destabilizzazione come una perdita di certezze, Trudy Benson inserisce invece la vivacità, la capacità di trovare proprio in quell’elemento di rottura un’opportunità incredibile di abbandonare la propria zona sicura per lasciarsi trascinare verso quel vento nuovo che un attimo dopo sopraggiungerà. Lo scompiglio è pertanto un gancio positivo, un modo per ricevere il messaggio energetico della realtà circostante che induce la persona a guardarsi dentro fino in fondo e a comprendere che forse è davvero giunto il momento di compiere un passo in avanti, di salire un gradino verso un futuro diverso da quello previsto.

D’altro canto però, l’autrice appare consapevole di quanto l’esperienza passata sia funzionale a procedere in maniera più equilibrata, ricordando le crepe e le sbrodolature di azioni e decisioni che hanno costruito la coscienza attuale; questo è probabilmente l’intento espressivo della tela Circling Back (Tornare indietro) dove l’atto del tornare equivale al voltarsi per comprendere, per ricordare senza rinnegare ciò che è accaduto bensì piuttosto ringraziando per l’esperienza che ne è seguita, come se in fondo senza quel percorso precedente non sarebbe stato possibile trovarsi nel punto esatto da cui il gesto del guardare si concretizza. La tonalità predominante qui è il giallo, il colore del sole, dell’allegria, della luminosità essenziale all’essere umano per sorridere alla vita e a credere che le cose possono solo andare meglio, proprio perché è l’atteggiamento a determinare la capacità di apprendere e considerare come insegnamento fondamentale ogni cosa che si verifica, compreso persino quell’attimo di nostalgia e di memoria di ciò che ormai si trova alle spalle.

In Like a Song emerge tutto il lirismo della pittura di Trudy Benson perché qui le figure geometriche, essenzialmente quadrati o rombi di diverse ma tenui tonalità, sembrano letteralmente danzare sulla tela, sembrano muoversi al ritmo di una musica silenziosa che risuona nella mente dell’autrice fino a giungere alle corde interiori dell’osservatore, il quale coglie quel sottile e delicato movimento, lo interiorizza e ne viene ammaliato esattamente in virtù di quegli immancabili reticoli che in questo caso evocano le righe di un pentagramma.

Trudy Benson ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre personali e collettive in Austria, Germania, Svezia, Belgio, Francia, Svizzera, Lussemburgo e ovviamente in USA e alcune sue opere fanno parte di collezioni pubbliche e musei a Beirut, New York, Portland e Londra.

TRUDY BENSON-CONTATTI

Email: info@milesmcenery.com

Sito web: www.trudybenson.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/trudy.benson.7

Instagram: www.instagram.com/trudybenson/

Abstract Art in constant motion by Trudy Benson, where forms are interconnected in their mobility

In contemporary reality, it is difficult to remain fixed on ideas and considerations, precisely because the perpetually changing times and the inevitable developments that arise from them prevent individuals from having well-defined fixed points; from an artistic point of view, this feeling can be translated, on the one hand, into the need to distance from reality in order to highlight the need to observe everything from a point of view less influenced by aesthetic distractions and, on the other hand, by emphasising the overlapping and fluctuating energy flow that runs beneath everyday life and cannot help but be perceived. Today’s protagonist transforms and mixes the characteristics of many interpretative facets of Abstract Art to create a hypnotic style full of chromatic vivacity.

The early 20th century coincided with an emerging need to demonstrate how different art was and how it could be considered as such while detaching itself from observed reality, from the reproduction of images that the eye was accustomed to seeing in everyday life; experimenting and devising movements that showed how plastic gestures and the lack of form attributable to reality could be independent and sufficient in themselves to the point of renouncing even the subjectivity of the artist who created the work were the cornerstones of all the different forms of Abstract Art. Whereas Vassily Kandinsky‘s Lyrical Abstraction sought to maintain a link with interiority through the fluctuation of shapes and tones that harmonised with the sensations experienced by the author while listening to classical music, Suprematism chose a more geometric approach, reducing the colour scale only to primary colours while maintaining a sense of instability in the forms, an arrangement that still included a sense of movement.

This movement was then completely rejected by the expressive rigour of De Stijl, where the only geometric shapes accepted by the founders of the movement, Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, were rectangles, squares and straight lines. For them, what mattered was to affirm the superiority of plastic perfection in its sterility, enhanced by primary colours alone, without being influenced by the external environment or by the world of sensations and emotions that, in the complex period between the two world wars for many artists it was better not to consider. However, it was precisely this rigour that soon made De Stijl too distant from engagement and, above all, too closed to the variations that would have allowed it to continue over time.

This did happen, however, thanks to the birth of Geometric Abstractionism, where the colour range was considerably expanded, introducing unprecedented possibilities, and forms considered impure by Mondrian, such as circles, diagonals, rhombuses, hexagons, and everything that had previously been absolutely rejected. Transparencies and overlaps began to instil an emotional sense in the observer, which was also evoked by the most geometric member of the Der Blaue Reiter group, Paul Klee, who was perhaps the first to link geometry to the feelings of the artist. Not only that, but a few decades later, around the 1950s, some exponents of Abstract Expressionism used Tachisme as a geometric subdivision of the canvas into different sunny and engaging shades capable of arousing positive feelings in the observer and communicating the artist’s narrative personality. The reference is to Hans Hoffman, a leading figure in world painting who succeeded in introducing geometry into emotion, belonging to a movement that rejected any expressive rigour that did not include the desire to overwhelm and engage the observer.

American artist Trudy Benson evolves and revolutionises the traces left in the past by her predecessors to develop a style in which vibrant and playful colours, drawing on Hoffman‘s chromatic heritage, create panels that seem to move on the canvas, overlapping and yet remaining tied to each other, as if she wanted to emphasise the interconnectedness that belongs to contemporary reality without highlighting its negative connotations, but rather accepting this fact and transforming it into a sense of community, albeit with a different meaning from the conception of the past. In other canvases, however, she renounces geometry to underline fluidity and the constant fluctuation of a reality so elusive that it requires abstraction, looking within oneself and listening only to the rhythm of one’s thoughts and emotions, thus reconnecting with Vassily Kandinsky‘s moving forms. Even in this second series of works, which are softer in tone, appears the constant theme of interconnectedness as if Trudy Benson wanted to put in evidence that, within a mobile and elusive everyday life, the only anchor to cling to is family, emotional and relational ties, in short, everything that reminds each individual how much they matter to the people who are part of that network.

From another point of view, however, it is impossible not to notice the reference to electrical mechanisms, to those circuits that are ultimately the basis of all modernity, of everything that belongs even to that now indispensable object known as the computer, which has become indispensable in everyday life. Here, therefore emerges a different interpretation of Trudy Benson‘s works, because in this case the grid becomes an automatism, something functional to progress that seems impossible to give up, as if it trapped those who created and then executed it. Yet, even with this second consideration, the colour range hints at the author’s approach to life, which leads her to always look at the glass as half full, emphasising the human ability to adapt to situations, changes, to the layers of experiences and circumstances that inevitably change reality and to which one can only surrender because resistance would be a source of frustration and a waste of energy that is no longer functional to the individual’s evolution. Also in the work Chaos, considering how the unexpected can be a source of stress for most people who see destabilisation as a loss of certainty, Trudy Benson instead introduces liveliness, the ability to find in that very element of disruption an incredible opportunity to leave one’s comfort zone and let oneself be carried away by the new wind that will arrive a moment later.

Disruption is therefore a positive hook, a way of receiving the energetic message of the surrounding reality that induces the person to look deep inside themselves and understand that perhaps the time has really come to take a step forward, to climb a step towards a future different from the one expected. On the other hand, however, the author seems aware of how much past experience is useful in moving forward in a more balanced way, remembering the cracks and spills of actions and decisions that have built the current consciousness; this is probably the expressive intent of the canvas Circling Back, where the act of returning is equivalent to look back to understand, to remember without denying what has happened, but rather giving thanks for the experience that followed, as if, ultimately, without that previous journey, it would not have been possible to find oneself at the exact point from which the act of looking takes shape.

The predominant tone here is yellow, the colour of the sun, of joy, of the brightness essential for human beings to smile at life and believe that things can only get better, precisely because it is attitude that determines the ability to learn and consider everything that happens as a fundamental lesson, including even that moment of nostalgia and memory of what is now behind. In Like a Song emerges all the lyricism of Trudy Benson‘s painting because here the geometric figures, essentially squares or rhombuses of different but tender shades, seem to literally dance on the canvas, seem to move to the rhythm of a silent music that resonates in the artist’s mind until it reaches the inner chords of the observer, who grasps that subtle and delicate movement, internalises it and is enchanted by it precisely because of those inevitable grids that in this case evoke the lines of a pentagram. Trudy Benson has participated in solo and group exhibitions in Austria, Germany, Sweden, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Luxembourg and, of course, the United States and some of her artworks are part of public collections and museums in Beirut, New York, Portland and London.