Nell’arte contemporanea alcuni autori tendono a cercare di districarsi nel groviglio di sensazioni e di emozioni che li avvolge senza riuscire a liberarsi dalla complessità che il mondo moderno porta inevitabilmente con sé; di conseguenza il loro linguaggio artistico si adegua a quel tipo di approccio mostrando sfaccettature ermetiche e spesso inafferrabili allo sguardo. Il protagonista di oggi al contrario si avvicina a uno stile decisamente immediato e comprensibile, fanciullesco nella forma ma più approfondito e introspettivo nella sostanza, mettendo in evidenza desideri, sogni e riflessioni sul vivere attuale.

Intorno alla fine dell’Ottocento, seguendo la scia rivoluzionaria che stava investendo l’arte europea in virtù della quale furono introdotte nuove regole stilistiche che ruppero le precedenti per avviare il processo avanguardista che seguì di lì a poco, si delineò tra gli altri un nuovo genere pittorico in cui gli interpreti erano per lo più privi di una formazione accademica o di una preparazione specifica ma avvertivano la necessità di lasciar fuoriuscire il loro innato talento attraverso l’arte. Rousseau il Doganiere fu il primo autore, nonché fondatore, dell’Arte Naïf che raccolse diverse sfaccettature espressive e che, nei primi periodi, concentrò la figurazione su un mondo immaginativo, ingenuo, perché proprio questo è il significato in francese del termine naïf, e quasi sognante, raccontato attraverso un tratto pittorico semplice, privo di prospettiva o di senso della proporzione, con colori stesi in modo uniforme e molto spesso miniaturizzato. Laddove Rousseau fu in grado di raccontare le atmosfere della giungla semplicemente immaginandole, perché di fatto non le aveva mai viste davvero, l’italiano Antonio Ligabue invece non poté fare a meno di raccontare se stesso, con i suoi limiti, e le piccole certezze costituite dai luoghi in cui aveva vissuto da uomo povero e incapace di gestire il talento e un successo che per breve tempo era arrivato e poi di nuovo sfuggito. Il movimento si sviluppò e ben presto si diffuse in tutto il vecchio continente, dove ebbe grandi esponenti in Francia con Camille Bombois che rappresentò non solo il mondo miniaturizzato che fu una delle caratteristiche principali dell’evoluzione del Naïf, bensì anche personaggi quasi fiabeschi del mondo del circo; André Bauchant che si concentrò sulla natura e sull’uomo in relazione con essa, mantenendo una gamma cromatica reale pur raccontando ambientazioni idilliache; nella ex Jugoslavia ad affermarsi fu lo stile minuzioso e romantico di Ivan Generalić, dove la semplicità delle immagini era associata alla quotidianità dei posti familiari all’artista, e da cui emergevano però anche temi esistenziali abilmente celati dall’apparente ingenuità espressiva delle scene e dei suoi protagonisti.

In Italia, oltre al celeberrimo Ligabue, vi fu un altro grande esponente del movimento, il ternano Orneore Metelli che mantenne una raffigurazione miniaturizzata ma piena di vita quotidiana, di folla nelle piazze e nelle occasioni di socializzazione che raffigurava. Anche gli Stati Uniti ebbero una grandissima interprete del Naïf in Grandma Moses che incantò gli appassionati del movimento di tutto il mondo con la sua gamma cromatica tenue, delicata, luminosa, a sottolineare la necessità di un legame con la spontaneità positiva, con la piacevolezza del vivere che proprio dalle piccole cose poteva emergere. Non si può tuttavia dimenticare l’accezione Metafisico Surrealista che il Naïf ebbe con una delle più importanti donne artiste di ogni tempo, la messicana Frida Kahlo, la quale utilizzò la semplicità figurativa per raccontare i traumi e le sofferenze subite, che sarebbero apparse troppo crude scegliendo uno stile più realista, e al contempo per permettere all’osservatore di scendere in profondità del suo pensiero e del suo messaggio lasciandolo avvicinarsi proprio per l’innocenza di uno stile essenziale e di facile approccio.

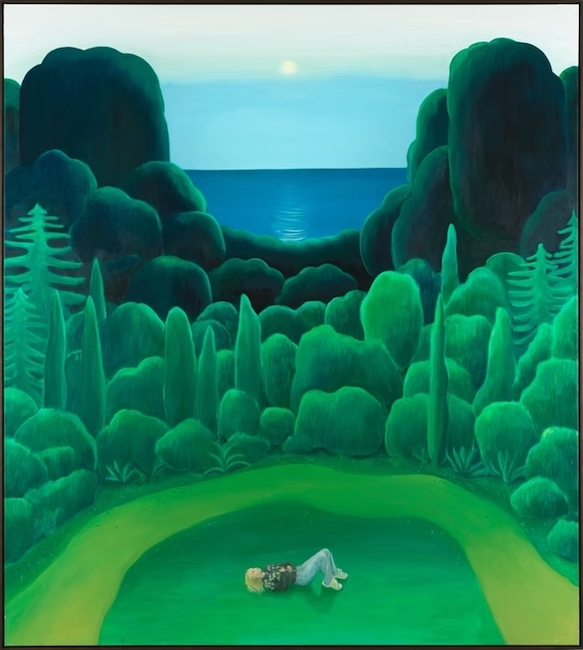

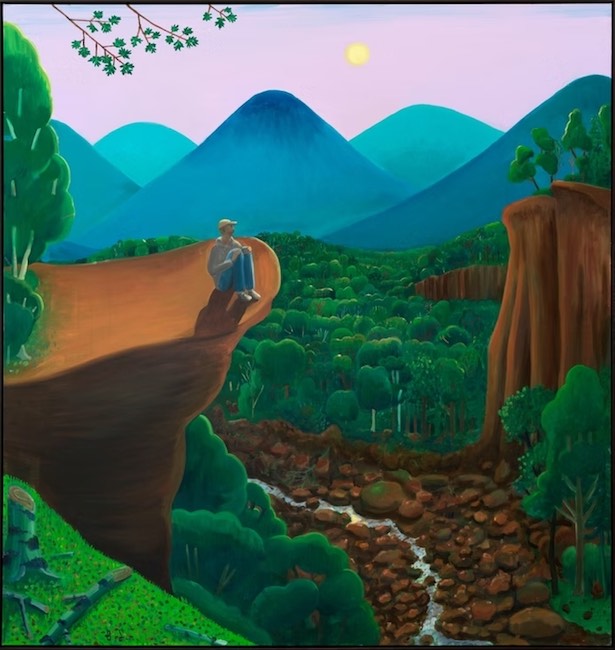

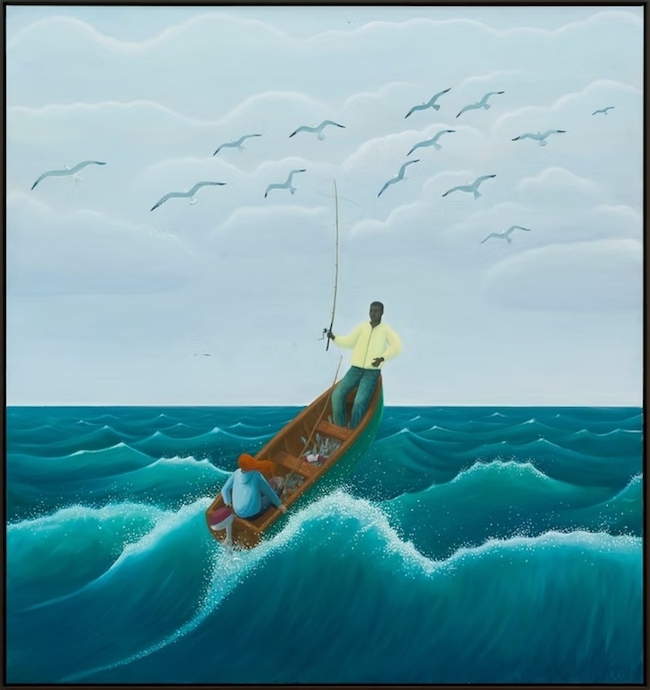

L’artista belga Ben Sledsens sceglie l’approccio sognante e fanciullesco del Naïf per osservare un mondo ideale, realizzando ambientazioni al di fuori dallo spazio e dal tempo, come se volesse sospendere l’esistenza in una bolla di piacevolezza all’interno della quale tutto appare più morbido e ovattato; al contempo dalle sue tele emerge anche l’attitudine Metafisica che aveva contraddistinto il suo conterraneo René Magritte e che si manifesta in quel significante nascosto dietro una gamma cromatica fiabesca, dietro paesaggi semplici e spontanei che però sollecitano riflessioni esistenziali in cui l’osservatore inevitabilmente si ritrova.

Dunque l’Arte Naïf in un certo senso mantiene una semplicità solo formale mentre scende nelle profondità dell’intimo umano e delle domande universali di oggi come di ieri entrando nella dimensione dell’Esistenzialismo Metafisico. La miniaturizzazione è una delle caratteristiche distintive delle opere di Ben Sledsens, perché in fondo approfondire tematiche umane deve richiedere uno sforzo di attenzione ben diverso dallo sguardo veloce e superficiale a cui la contemporaneità ha abituato l’individuo, ecco perché la vera essenza di ogni tela si svela solo soffermandosi sui dettagli e andando a esplorare il motivo del legame tra l’immagine e il titolo, che diviene così integrazione indispensabile dell’opera.

La gamma cromatica a volte appare completamente decontestualizzata poiché emanazione del sentire dei suoi personaggi, desiderio di astrazione da una realtà ordinaria che non consente loro di essere pienamente se stessi, mentre in altre si avvicina di più alle tonalità effettive perché necessarie a indurre il fruitore a credere di essere davanti a qualcosa di facilmente fruibile e riconoscibile per poi trovarsi nell’universo del dubbio, delle domande senza risposta, delle scelte attribuibili al caso ma poi di fatto figlie del momento contingente e semi delle conseguenze che da esse si genereranno.

Estremamente Metafisica è l’opera Crossroads in cui il panorama boschivo si apre a due opzioni rappresentate da due strade parallele ma separate, come se Ben Sledsens volesse sottolineare quanto frequentemente l’uomo si trovi davanti a un bivio che lo costringe a prendere una decisione, più o meno importante che sia ma sempre portatrice di eventi che si sviluppano partendo proprio da quel punto iniziale. L’apparenza è la medesima, le due vie conducono entrambe verso un cielo limpido dunque l’autore suggerisce che forse nella vita non esistono scelte giuste o scelte sbagliate, semplicemente esistono percorsi da intraprendere perché nel preciso istante della decisione sono probabilmente quelle più affini all’evoluzione di chi si appresta a incamminarsi.

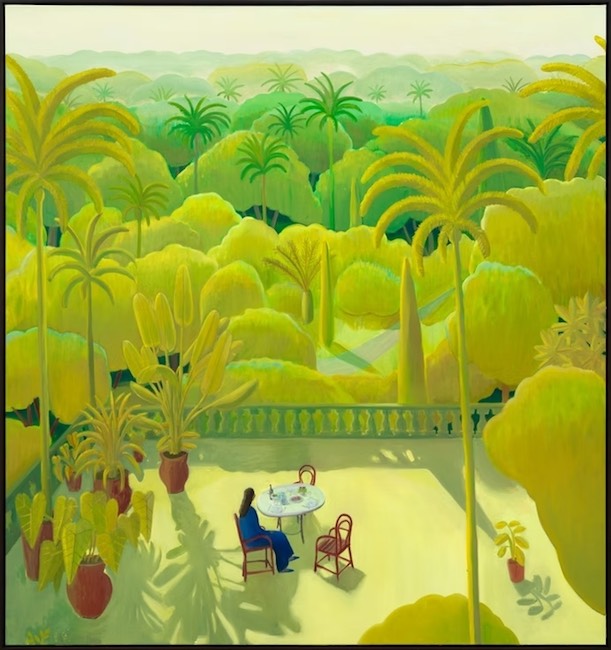

Anche Dinner for Three rientra nella serie di opere in cui l’apparire sognante viene condotto dal titolo a soffermarsi sulle tre sedie di cui due vuote, lasciando percepire un’attesa forse disillusa oppure la solitudine che si prova dopo una perdita importante quando ciò che era una certezza prima diventa un vuoto incolmabile che non può essere riempito neanche calandosi in un’atmosfera paradisiaca come quella raccontata da Ben Sledsens. Il fruitore è chiamato a riflettere sull’illusione dei tempi moderni di sentirsi parte di una comunità, quella virtuale, che di fatto, una volta spento lo schermo del pc lascia le persone da sole completamente destabilizzate da un silenzio visivo che non sono più capaci di sostenere; d’altro canto però l’invito è quello di lasciarsi andare al bello della natura, alla possibilità di farsi avvolgere e trasportare in un mondo diverso, più piacevole, più a contatto con il sé più autentico, anche se questo implica la possibilità di fare i conti con una solitudine che però, una volta accettata, può essere riempita di nuove opportunità.

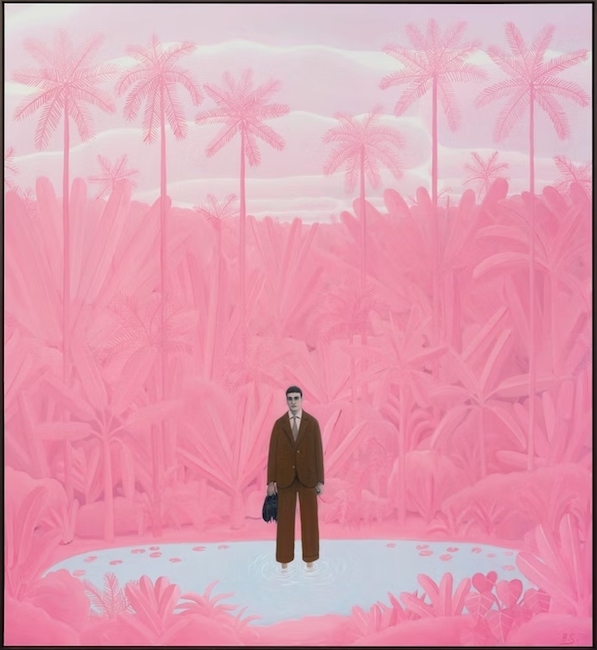

Pink Mirage si sposta invece verso la dimensione del sogno, di quel desiderio inconfessato eppure fortemente radicato dentro l’essere umano di evadere da una contingenza insoddisfacente, omologante al punto di spingere verso il viaggio immaginario che possa condurre in una condizione più idilliaca; l’uomo che Ben Sledsens rende protagonista è vestito in maniera ordinaria, forse è un impiegato che si sente intrappolato nella sua routine, e dunque viene trasportato in un universo rosa, pieno di palme e di un piccolo laghetto dove può immergere i piedi abbandonandosi alla magia visiva e alla leggera brezza che si immagina avvolgere quell’incantato paesaggio color pastello. Il miraggio è dunque più un’utopia, un desiderio di cambiare tutto ciò che rende cupa l’ordinarietà e il vivere contemporaneo, immergendosi in una bolla di benessere che induce l’uomo a compiere un gesto rivoluzionario per il suo schema abituale, quello cioè di togliersi le scarpe rinunciando a una formalità che nella vita reale fa ormai parte di lui.

Ben Sledsens è nato ad Anversa, si è formato alla Royal Academy di Fine Arts della sua città, dunque il suo Naïf è una scelta ponderata e desiderata, non più uno stile adottato per mancanza di formazione come accadde alla nascita del movimento, e nel 2015 ha ricevuto il KoMASK Award per la pittura, presentato dalla Royal Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts del Belgio. Le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni permanenti di importanti istituzioni.

BEN SLEDSENS-CONTATTI

Email: info@timvanlaeregallery.com

Sito web: www.timvanlaeregallery.com/ben-sledsens

Instagram: www.instagram.com/bensledsens/

Ben Sledsens’ Metaphysical Naïf, when simplicity meets existentialist reflection

In contemporary art, some artists tend to try to untangle from the intricacy of sensations and emotions that surround them without managing to free themselves from the complexity that the modern world inevitably brings with it; consequently their artistic language adapts to that type of approach by showing hermetic and often elusive facets to the eye. Today’s protagonist, on the contrary, approaches a decidedly immediate and understandable style, childlike in form but more profound and introspective in substance, highlighting desires, dreams and reflections on contemporary life.

Towards the end of the 19th century, following the revolutionary wave that was sweeping through European art, which introduced new stylistic rules that broke with the previous ones to initiate the avant-garde process that followed shortly thereafter, emerged a new pictorial genre in which the artists were mostly without academic training or specific preparation but felt the need to let their innate talent flow through art. Rousseau the Customs Officer was the first author and founder of Naïve Art, which brought together various expressive facets and, in its early stages, focused on depicting an imaginative, ingenuous world, because this is precisely the meaning of the French term naïf, and almost dreamlike, told through simple brushstrokes, devoid of perspective or sense of proportion, with colours applied uniformly and very often miniaturised.

Where Rousseau was able to describe the atmosphere of the jungle simply by imagining it, because he had never actually seen it, the Italian Antonio Ligabue, on the other hand, could not help but describe himself, with his limitations and the small certainties provided by the places where he had lived as a poor man, unable to manage his talent and the success that had briefly come his way and then slipped away again. The movement developed and soon spread throughout the old continent, where it had great exponents in France with Camille Bombois, who represented not only the miniaturised world that was one of the main characteristics of the evolution of Naïf, but also almost fairy-tale characters from the world of the circus; André Bauchant focused on nature and man in relation to it, maintaining a realistic colour palette while depicting idyllic settings; in the former Yugoslavia emerged the meticulous and romantic style of Ivan Generalić where the simplicity of the images was associated with the everyday life of places familiar to the artist, but from which came out also existential themes, skilfully concealed by the apparent expressive naivety of the scenes and their protagonists. In Italy, in addition to the famous Ligabue, there was another great exponent of the movement, Orneore Metelli from Terni, who maintained a miniaturised representation but full of everyday life, crowds in squares and social occasions. The United States also had a great interpreter of Naïf in Grandma Moses, who enchanted fans of the movement around the world with her soft, delicate, luminous colour palette, emphasising the need for a connection with positive spontaneity and the pleasure of living that could emerge from the little things. However, we cannot forget the Metaphysical Surrealist meaning that Naïf had with one of the most important female artists of all times, the Mexican Frida Kahlo, who used figurative simplicity to recount the traumas and sufferings she had endured, which would have appeared too crude if had been chosen a more realistic style, and at the same time to allow the observer to delve deeply into his thoughts and message, drawing them in precisely because of the innocence of an essential and accessible style. Belgian artist Ben Sledsens chooses the dreamy, childlike approach of Naïf to observe an ideal world, creating settings outside of space and time, as if he wanted to suspend existence in a bubble of pleasantness within which everything appears softer and more muffled; at the same time, his canvases also reveal the Metaphysical attitude that characterised his compatriot René Magritte, manifested in the meaning hidden behind a fairy-tale colour palette, behind simple and spontaneous landscapes that nevertheless prompt existential reflections in which the observer inevitably finds themselves.

Thus, Naïve Art, in a certain sense, maintains a simplicity that is only formal, while delving into the depths of the human soul and the universal questions of today as well as yesterday, entering the dimension of Metaphysical Existentialism. Miniaturisation is one of the distinctive features of Ben Sledsens‘ works, because ultimately, exploring human themes requires a level of attention that is very different from the quick, superficial glance to which contemporary society has accustomed individuals. This is why the true essence of each canvas is revealed only by lingering over the details and exploring the connection between the image and the title, which thus becomes an indispensable part of the work. The colour range sometimes appears completely decontextualised as it emanates from the feelings of his characters, a desire for abstraction from an ordinary reality that does not allow them to be fully themselves, while in others it is closer to the actual shades because they are necessary to induce the viewer to believe that they are looking at something easily accessible and recognisable, only to find themselves in a universe of doubt, unanswered questions, choices attributable to chance but in fact the result of the contingent moment and the seeds of the consequences that will be generated by them.

Extremely metaphysical is the work Crossroads, in which the wooded landscape opens up to two options represented by two parallel but separate roads, as if Ben Sledsens wanted to emphasise how often man finds himself at a crossroads that forces him to make a decision, whether important or not, but always leading to events that unfold from that starting point. The appearance is the same, both roads lead to a clear sky, so the author suggests that perhaps in life there are no right or wrong choices but simply paths to take because at the precise moment of decision they are probably the ones most suited to the evolution of those who are about to set off. Dinner for Three is also part of a series of works in which the dreamlike appearance is led by the title to dwell on the three chairs, two of which are empty, suggesting a perhaps disillusioned expectation or the loneliness one feels after a significant loss when what was once a certainty becomes an unbridgeable void that cannot be filled even by immersing in a paradisiacal atmosphere such as that described by Ben Sledsens. The user is invited to reflect on the illusion of modern times of feeling part of a community, the virtual one, which in fact, once the computer screen is turned off, leaves people completely alone and destabilised by a visual silence that they are no longer able to bear. On the other hand, however, the invitation is to let oneself go to the beauty of nature, to the possibility of being enveloped and transported to a different world, more pleasant, more in touch with one’s authentic self, even if this implies the possibility of coming to terms with a loneliness that, once accepted, can be filled with new opportunities.

Pink Mirage, on the other hand, moves towards the dimension of dreams, of that unconfessed yet deeply rooted desire within human beings to escape from an unsatisfactory, conformist reality, to the point of pushing them towards an imaginary journey that can lead to a more idyllic condition. The man Ben Sledsens portrays is dressed in ordinary clothes, perhaps an office worker who feels trapped in his routine, and is transported to a pink universe full of palm trees and a small pond where he can dip his feet, abandoning himself to the visual magic and the light breeze that he imagines enveloping that enchanted pastel-coloured landscape. The mirage is therefore more of a utopia, a desire to change everything that makes everyday life and contemporary living gloomy, immersing in a bubble of well-being that induces the man to perform a revolutionary gesture for his usual pattern, that is to take off his shoes, renouncing a formality that in real life has become part of him. Ben Sledsens was born in Antwerp and trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in his city, so his Naïf style is a deliberate and desired choice, no longer a style adopted due to a lack of training as was the case when the movement began. In 2015, he received the KoMASK Award for painting, presented by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts in Belgium. His artworks are part of the permanent collections of important institutions.