L’attitudine a rivisitare, reinterpretare e dare un nuovo volto agli stili che si sono sviluppati nel più recente passato, è tipico degli autori contemporanei che attingono agli esperimenti pittorici precedenti per infondere carattere e riconoscibilità al proprio linguaggio espressivo. Il fascino dei tempi moderni si struttura esattamente in questa sintesi tra presente e passato che da un lato mostra quanto l’arte in generale, e la pittura in particolare, sia ciclica ed evolutiva, perché nel corso dei secoli ogni stile, anche il più innovativo e avanguardista, ha attinto a radici preesistenti pur stravolgendole e adattandole ai tempi, mentre dall’altro svela la capacità degli autori attuali di trasformare le linee guida sulla base della propria indole narrativa. Ray Piscopo è uno di quei creativi che ama sperimentare, misurarsi con sfide sempre nuove ma soprattutto ama lasciare un suo personale segno, un carattere stilistico ben definito mostrando un eccentrico e affascinante modo di raccontare l’isola da cui proviene e in cui vive, Malta.

La pittura paesaggistica conobbe un inedito slancio, e soprattutto un’ascesa verso l’arte di primo livello, rispetto a quanto avvenuto fino a poco prima, con il Romanticismo Inglese dove grandi autori come William Turner e John Constable misero in luce la bellezza della natura, più irrequieta e tempestosa quella del primo, più serena e distensiva quella del secondo. Ovviamente agli inizi dell’Ottocento la figurazione era strettamente legata alla realtà osservata, eppure, in particolar modo con Turner, emerse un’inedita rappresentazione degli scenari in cui fuoriusciva la sensazione percepita dall’autore e un insolito utilizzo della luce che diveniva il punto focale delle sue tele. Qualche decennio dopo, superata la seconda metà del secolo, l’approccio del maestro inglese fu oggetto di studio, approfondimento e modificazione da parte di tutti gli autori che aderirono all’Impressionismo, movimento in cui non solo il paesaggio divenne centrale, ma in cui si studiò un inedito modo di raccontare la realtà rinunciando al disegno preparatorio, rinunciando al lavoro in studio per dipingere all’aria aperta e smettendo di mescolare il colore sulla tavolozza apponendolo sulla tela a piccoli tocchi di colore puro che si andava poi a comporre come immagine sulla retina dell’osservatore esaltando proprio la luminosità tanto cara a Turner.

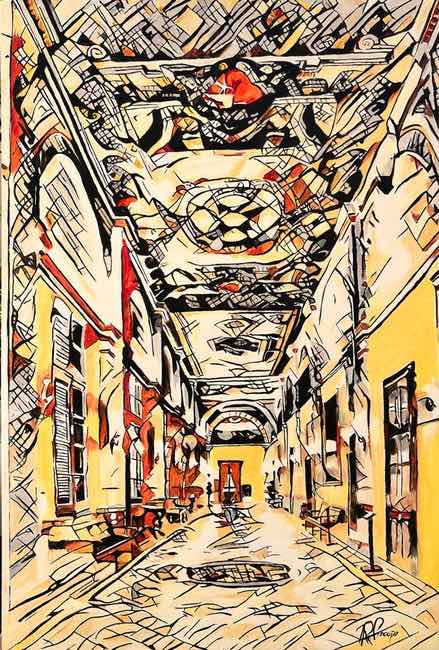

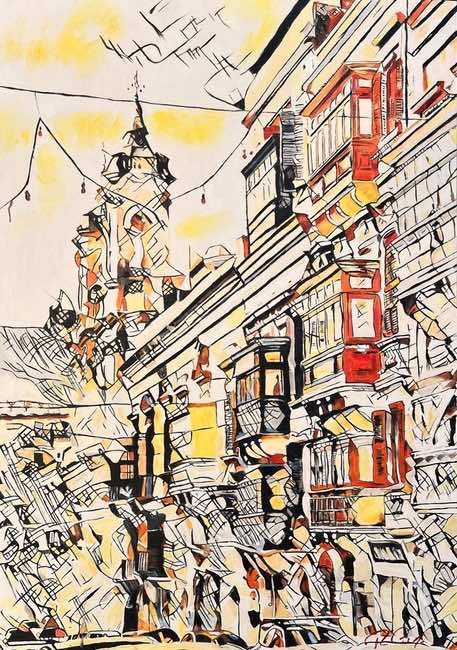

Il principio della frammentazione impressionista si affermò in maniera decisa sulla spinta di quel desiderio di rinnovare l’arte stravolgendo le regole accademiche e creando uno stile dove la luce veniva rarefatta e amplificata fino a essere essenza stessa di un’opera d’arte. Da quel momento in avanti la pittura divenne una costante sperimentazione, l’evoluzione naturale di scoperte del passato che erano spunto e al contempo base di partenza di quell’adeguarsi al cambiamento veloce dei tempi al quale anche l’arte non poteva sfuggire. Tra gli stili che proseguirono il cammino dell’Impressionismo ve ne furono in particolare due che estremizzarono il tema della scomposizione dell’immagine, il Puntinismo in cui la riduzione in puntini andava a creare scenari distinguibili solo allontanandosi dalla tela e che utilizzò una gamma cromatica irreale più vicina alla poetica espressionista, e il Divisionismo italiano dove invece il frazionamento avveniva attraverso sottilissime linee parallele grazie alle quali la definizione e la luce erano incredibilmente palpitanti e vicine al reale; Giovanni Segantini fu il maestro di questo stile e nei suoi paesaggi non si può non notare la forte luminosità, l’amore per la natura e il desiderio di riprodurre ciò che il suo sguardo coglieva quando si trovava davanti alle scene poi ritratte. L’artista maltese Ray Piscopo personalizza le teorie della suddivisione pittorica, le stravolge, le fa sue e le applica fondendole a un approccio pittorico in cui l’Espressionismo predomina dal punto di vista cromatico e anche da quello della narrazione dell’osservato, ma dove poi il tocco divisionista termina e completa la base rappresentativa come a infondere sui suoi paesaggi dedicati all’isola di Malta un aspetto scolpito, tanto quanto il tempo che ha lasciato intatte quelle costruzioni, quegli edifici storici che affascinano non solo chi percorre le vie dell’isola bensì anche i suoi abitanti che ogni giorno vi si trovano immersi.

In questo suo utilizzare le linee divisorie per completare il racconto visivo, Ray Piscopo mostra tutto il suo spirito contemporaneo, quasi sembra volersi avvicinare ai Graffiti della Street Art per sottolineare quanto il passato non possa escludere l’accettazione di un presente che non vuole sconvolgerlo anzi, cerca di convivere con esso.

Ma ciò che colpisce più di tutto è la veste inedita che l’autore dà alla quotidianità e alla familiarità di monumenti, di vie, di scene di vita quotidiana che sono una scoperta per il viaggiatore mentre costituiscono la normalità per gli abitanti; e dunque la sua nuova interpretazione può essere sorprendente per entrambe le categorie di osservatori, proprio perché i paesaggi narrati partono dal visibile ma poi lo modificano filtrandolo con il sentire, con la capacità di andare al di là dell’immagine per svelare l’essenza di un luogo, e di un popolo, che hanno saputo mantenere intatta la loro anima tradizionale pur non rifiutando di camminare nell’attualità.

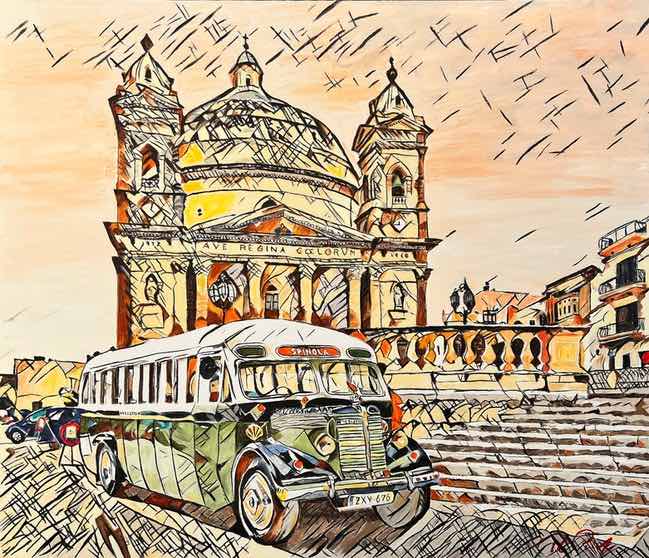

Nella sua nuova serie di opere, che sarà protagonista di una grande mostra presso il Wignacourt Museum di Rabat, Malta, per tutto il mese di dicembre, a emergere in maniera chiara e inequivocabile è la dominante cromatica che evoca la pietra calcarea con cui sono costruiti tutti gli edifici, le chiese e le fortificazioni fin dall’antichità, e che attraverso la trasformazione emozionale dell’autore vira verso il giallo tenue da cui si rivela l’amore per la sua terra, il desiderio di metterne in evidenza la luminosità e al contempo dissolvere la linea temporale tra passato e presente, tra tradizioni e semplicità del modo di vivere e l’immancabile contatto con il mare che circonda l’intera isola e che ha permesso agli abitanti di affrontare il progresso e le evoluzioni a un ritmo più a misura d’uomo, meno frenetico rispetto alle grandi metropoli occidentali. In qualche modo la tecnica di Ray Piscopo può essere definita MacroImpressionismo, o PostDivisionismo se si vuole concedersi il lusso di coniare nuovi termini affini a un autore che sfugge alle definizioni, perché le sue opere diventano più distinguibili allontanandosi da esse eppure l’apporto emozionale e intenso con cui egli descrive ciascuno scorcio delle innumerevoli e affascinanti località di Malta attrae lo sguardo che è pertanto chiamato ad avvicinarsi alla tela per andare a scoprire quei dettagli stilizzati riconoscendo il palazzo, la via o il luogo esatto a cui si riferiscono.

Emblematica di questo concetto espressivo di Piscopo è l’opera Pinto Wharf che ritrae il Valletta Waterfront utilizzando il suo antico nome per sottolineare la coesistenza tra modernità e tradizione, tra ciò che è stato edificato anticamente come roccaforte di accesso verso il mondo esterno all’isola e la sua funzione pratica di porta del commercio internazionale e, nei tempi contemporanei, porto di attracco per navi turistiche. Ciò che colpisce della narrazione dell’autore è quell’indefinitezza espressiva che dissolve i dettagli a un primo sguardo, ma poi li rende più riconoscibili ed evidenti concentrandosi sulle linee scure che guidano l’occhio verso la chiarezza, come fossero una traccia e un riferimento attraverso cui ritrovarsi. In primo piano quelle imbarcazioni che costituiscono, e hanno costituito, l’essenza stessa dell’isola di Malta mentre sullo sfondo si intravedono le facciate degli edifici coloniali anticamente sedi di magazzini e di depositi delle merci trasformate oggi in ristoranti, negozi e caffè alla moda; la visione dell’autore è perciò sospesa tra nostalgia di un passato indimenticabile e l’affetto verso la sua capacità di rigenerarsi illuminando di nuova luce quel magnifico lungomare in stile barocco.

Il dipinto Tal Halib attinge invece alla memoria storica di quei mestieri ormai estinti, di quelle abitudini quotidiane che mettevano in stretta correlazione umana il fornitore di un servizio e chi il servizio lo riceveva interagendo in maniera proattiva e non distaccata come avviene oggi acquistando prodotti nei supermercati. L’antico lavoro del lattaio, che andava direttamente casa per casa con i suoi animali assicurando così la freschezza del prodotto, è ormai estinto eppure Ray Piscopo lo rende protagonista di una sua opera perché è solo attraverso il ricordo di chi quelle atmosfere le ha vissute che può essere lasciata una traccia del passato alle generazioni future. Qui la figurazione è più nitida mentre i tratti grafici, le tipiche linee divisioniste di Ray Piscopo, sembrano voler incidere e sottolineare l’appartenenza di quella scena a un tempo antico, a una dimensione lontana che porta con sé i segni della storia e tuttavia è esempio di una connessione diversa tra gli individui, più empatica, più coinvolta e in qualche modo intima rispetto a quelle del vivere attuale.

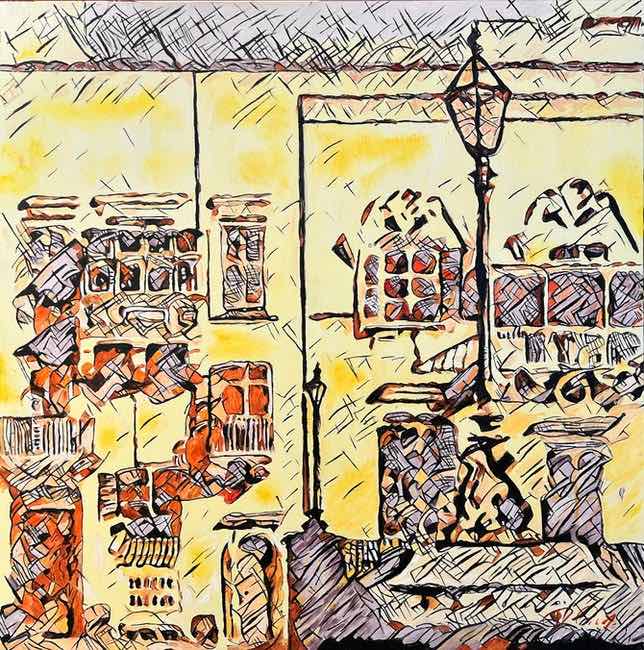

Il dipinto Gallaroiji fil-Belt 4 sposta invece l’attenzione sulla struttura architettonica della capitale dell’isola, La Valletta, di cui racconta i balconi a bovindo, sovrapposti gli uni agli altri a creare una moltitudine visiva in continuità che contraddistingue i palazzi del centro città, ma anche per ricordare il senso di comunità, quello stringersi degli abitanti gli uni agli altri e a convivere in armonia in uno spazio ristretto come quello di Malta e proprio per questo accentuare l’unione pur mantenendo ciascuno la propria individualità, mettere l’accento sulla capacità di tramandare la storia e conservare la bellezza tradizionale dei palazzi perché un popolo può restare autentico solo quando è in grado di guardare avanti, insieme e compatto, ricordando però tutto ciò che lo ha condotto nel presente, ed è proprio l’unirsi, il sapere quanto ciascuno fosse fondamentale per l’altro e per l’autonomia del piccolo stato, a costituire il punto focale dell’opera di Ray Piscopo che di fatto va oltre l’immagine graffiata simbolicamente con i segni del passaggio del tempo per raccontare la storia che si nasconde dietro la facciata esterna.

L’universo espressivo dell’autore, nella serie pittorica protagonista dell’esposizione di dicembre 2025 presso il Wignacourt Museum di Rabat, si mostra in tutta la sua eccentricità stilistica compiendo un affascinante percorso all’interno dell’essenza stessa dell’isola di Malta, dei suoi usi e costumi, del suo passato che sa sopravvivere a un presente che sembra voler andare in un’altra direzione, eppure nello sguardo di Ray Piscopo rimane solo un’altra delle evoluzioni che il suo popolo, e nel senso più ampio e universale l’umanità, compie senza tuttavia dimenticare mai ciò che è stato. Questo passaggio, questo appartenere a linee temporali diverse è proprio ciò che spinge l’autore alla scelta narrativa di quelle linee, quelle divisioni, quei segni contraddistintivi delle sue tele in uno stile unico dove l’innovazione si fonde con l’emozione per dar vita a un racconto insolito e affascinante, un punto di vista originale e ammaliante della sua amata isola.

RAY PISCOPO-CONTATTI

Email: piscopoart@gmail.com

Sito web: www.piscopoart.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/ray.piscopo

Instagram: www.instagram.com/raypiscopo/

The island of Malta and its artistic heritage protagonist of Ray Piscopo’s artworks between Divisionism and Expressionism

The tendency to revisit, reinterpret, and give a new face to styles that have developed in the recent past is typical of contemporary artists who draw on previous pictorial experiments to infuse character and recognizability into their own expressive language. The charm of modern times is structured precisely in this synthesis between the present and the past, which on the one hand shows how art in general, and painting in particular, is cyclical and evolutionary, because over the centuries every style, even the most innovative and avant-garde, has drawn on pre-existing roots while distorting them and adapting to the times, while on the other hand reveals the ability of current artists to transform guidelines based on their own narrative nature. Ray Piscopo is one of those creative authors who loves to experiment, to take on new challenges, but above all, he loves to leave his own personal mark, a well-defined stylistic character, showing an eccentric and fascinating way of portraying the island where he comes from and where he lives, Malta.

Landscape painting experienced an unprecedented surge, and above all an ascent to the highest level of art, compared to what had happened until shortly before, with English Romanticism where great artists such as William Turner and John Constable highlighted the beauty of nature, the former’s being more restless and stormy, the latter’s more serene and relaxing. Obviously, in the early 19th century, figurative art was closely linked to observed reality, yet, especially with Turner emerge a new representation of scenes, revealing the artist’s feelings and an unusual use of light, which became the focal point of his canvases. A few decades later, after the second half of the century, the English master’s approach was studied, explored, and modified by all the artists who adhered to Impressionism, a movement in which not only did landscape become central, but in which was studied an unprecedented way of depicting reality, renouncing preparatory drawings, renouncing studio work in favor of painting outdoors, and stopping mixing colors on the palette, instead applying them to the canvas in small touches of pure color that were then composed as an image on the observer’s retina, enhancing the luminosity so dear to Turner.

The principle of impressionist fragmentation became firmly established, driven by a desire to renew art by overturning academic rules and creating a style in which light was rarefied and amplified to the point of becoming the very essence of a work of art. From that moment on, painting became a constant experiment, the natural evolution of past discoveries that were both the inspiration and the starting point for adapting to the rapid changes of the times, which even art could not escape. Among the styles that continued the path of Impressionism, there were two in particular that took the theme of image decomposition to extremes: Pointillism, where the reduction to dots created scenes that could only be distinguished by moving away from the canvas and which used an unreal color range closer to expressionist poetics, and Italian Divisionism where the fragmentation took place through very thin parallel lines, thanks to which the definition and light were incredibly vibrant and close to reality.

Giovanni Segantini was the master of this style, and in his landscapes one cannot fail to notice the strong luminosity, the love of nature, and the desire to reproduce what his gaze captured when he stood before the scenes he later portrayed. Maltese artist Ray Piscopo personalizes theories of pictorial subdivision, distorts them, makes them his own, and applies by blending into a pictorial approach in which Expressionism predominates from a chromatic point of view and also from that of the narration of the observed, but where the divisionist touch ends and completes the representative base, as if to infuse his landscapes dedicated to the island of Malta with a sculpted appearance, as much as the time that has left those buildings intact, those historic houses that fascinate not only those who walk the streets of the island but also its inhabitants who find themselves immersed in them every day. In his use of dividing lines to complete the visual narrative, Ray Piscopo shows all his contemporary spirit, almost as if he wants to approach Street Art Graffiti to emphasize how the past cannot exclude the acceptance of a present that does not want to upset it but rather seeks to coexist with it. But what is most striking is the new look that the author gives to everyday life and the familiarity of monuments, streets, and scenes of daily life that are a discovery for the traveler but constitute normality for the inhabitants; and so his new interpretation may therefore come as a surprise to both categories of observers, precisely because the landscapes he depicts start from the visible but then modify it by filtering it through feeling, with the ability to go beyond the image to reveal the essence of a place and a people who have managed to keep their traditional soul intact while not refusing to move with the times.

In his new series of works, which will be featured in a major exhibition at the Wignacourt Museum in Rabat, Malta throughout the month of December 2025, what emerges clearly and unequivocally is the dominant color that evokes the limestone with which all buildings, churches, and fortifications have been built since ancient times, and which, through the author’s emotional transformation, shifts towards a soft yellow that reveals his love for his land, the desire to highlight its brightness and at the same time dissolve the timeline between past and present, between traditions and simplicity of life and the inevitable contact with the sea that surrounds the entire island and has allowed its inhabitants to face progress and evolution at a more human pace, less frenetic than in the great Western metropolises. In some ways, Ray Piscopo‘s technique can be defined as MacroImpressionism, or PostDivisionism if one wants to indulge in the luxury of coining new terms for an artist who defies definition, because his artworks become more distinguishable when moving away from them, yet the emotional and intense contribution with which he describes each glimpse of Malta’s countless fascinating locations attracts the gaze, therefore called upon to approach the canvas to discover those stylized details, recognizing the building, street, or exact location to which they refer.

Emblematic of this expressive concept of Piscopo is the work Pinto Wharf, which depicts the Valletta Waterfront using its ancient name to focus the attention on the coexistence of modernity and tradition, between what was built in ancient times as a stronghold of access to the world outside the island and its practical function as a gateway for international trade and, in contemporary times, a port of call for tourist ships. What is striking about the author’s narrative is the expressive vagueness that dissolves the details at first glance, but then makes them more recognizable and evident by focusing on the dark lines that guide the eye towards clarity, as if they were a trace and a reference through which to find oneself. In the foreground are the boats that constitute, and have always constituted, the very essence of the island of Malta, while in the background you can glimpse the facades of colonial buildings that were once warehouses and storage facilities for goods, now transformed into trendy restaurants, shops, and cafés; the artist’s vision is therefore suspended between nostalgia for an unforgettable past and affection for its ability to regenerate itself, illuminating the magnificent Baroque-style seafront with new light.

The painting Tal Halib, on the other hand, draws on the historical memory of those now extinct trades, those daily habits that created a close human connection between the service provider and the service recipient, interacting proactively and not detached as happens today when purchasing products in supermarkets. The ancient job of the milkman, who went directly from house to house with his animals, thus ensuring the freshness of the product, is now extinct, yet Ray Piscopo makes it the protagonist of one of his artworks because it is only through the memory of those who experienced those atmospheres that a trace of the past can be left for future generations. Here, the figuration is clearer, while the graphic features, Ray Piscopo‘s typical divisionist lines, seem to want to engrave and put in evidence the scene’s belonging to an ancient time, to a distant dimension that bears the marks of history and yet is an example of a different connection between individuals, more empathetic, more involved, and somehow more intimate than those of current life.

The painting Gallaroiji fil-Belt 4 shifts instead the focus to the architectural structure of the island’s capital, Valletta, depicting its bay windows, superimposed on each other to create a continuous visual multitude that characterizes the houses in the city center, but also to recall the sense of community, the closeness of the inhabitants to each other and their harmonious coexistence in a confined space such as Malta. For this reason, it accentuates unity while maintaining individuality, emphasizing the ability to pass on history and preserve the traditional beauty of the buildings, because a people can only remain authentic when he’s able to look ahead, together and united, while remembering everything that has led him to the present, and it is precisely this union, this awareness of how fundamental each was to the other and to the autonomy of the small state, that constitutes the focal point of Ray Piscopo‘s work, which in fact goes beyond the image symbolically scratched with the signs of the passage of time to tell the story hidden behind the external façade. The author’s expressive universe, in the pictorial series featured in the December 2025 exhibition at the Wignacourt Museum in Rabat, is displayed in all its stylistic eccentricity, taking us on a fascinating journey into the very essence of the island of Malta, its customs and traditions, and its past, which survives a present that seems to be heading in another direction. yet in Ray Piscopo‘s view, it remains just another of the evolutions that his people, and in the broadest and most universal sense, humanity, undergoes without ever forgetting what has been. This transition, this belonging to different timelines, is precisely what drives the author to choose those lines, those divisions, those distinctive marks on his canvases in a unique style where innovation blends with emotion to give life to an unusual and fascinating story, an original and captivating point of view of his beloved island.