Essere al di fuori degli schemi ha contraddistinto un considerevole numero di artisti fin dall’antichità perché la loro genialità e capacità di dar vita a qualcosa di nuovo, contrario persino alle convenzioni e alle regole stilistiche dei loro tempi, di concretizzava esattamente in quel percorrere una strada non battuta in precedenza, quella libertà imposta a se stessi di voler seguire solo e unicamente il loro istinto espressivo non conforme al momento storico in cui hanno vissuto. Allo stesso modo nel panorama artistico attuale di delineano figure artistiche che sfuggono alle regole, ne creano di proprie e lasciano che la loro essenza fuoriesca in maniera istintiva comunicando all’esterno ciò che spesso non riesce a essere spiegato con un mezzo diverso dalla pittura. Il protagonista di oggi appartiene a questo gruppo di creativi.

Già a partire dall’Olanda del periodo Fiammingo, dunque verso la fine del Quattrocento, un coraggioso artista, una voce fuori dal coro, cominciò a gettare le basi per quello che fu visto e poi raccolto come anticipazione dell’anticonformismo, della capacità di assecondare la propria natura anche laddove considerata folle, scandalosa, irriverente; Hieronymus Bosch, questo il nome del genio anticipatore del Surrealismo, utilizzò un stile non convenzionale ma innovatore per descrivere sarcasticamente il rapporto tra essere umano e imposizioni della religione, all’epoca molto forti, che erano fonte di frustrazione senza di fatto essere un deterrente nei confronti di comportamenti che venivano segretamente messi in atto. Le medesime tematiche, amplificate ma anche allargate ad altri settori esaltando la follia come un modo di essere che non doveva più incontrare giudizio e opposizione solo perché lontana dalle regole e dai luoghi comuni, furono accolte dal Surrealismo dove gli istinti e le pulsioni si univano anche al mondo dell’inconscio, evidenziando tutto ciò che normalmente veniva arginato dalla ragione. Salvador Dalì fu un ribelle ma soprattutto uno spirito libero che, sia nell’arte come nella vita, scelse di vivere secondo le proprie regole, raccontando pertanto nelle sue tele di mondi torbidi, impossibili in cui la sessualità e il tempo tornavano ossessivamente protagonisti; tanto quanto improbabili erano gli edifici e i paesaggi realizzati da Maurits Cornelis Escher la cui prospettiva confondeva lo sguardo e al tempo stesso attraeva per quel mistero inspiegabile su come una mente potesse riuscire a concepire qualcosa di tanto bizzarro e irreale. Bisognerà poi attendere gli anni Cinquanta del Novecento per trovarsi di fronte a una sorta di sintesi tra la confusione esecutiva dell’anticipatore Bosch e la liberazione di un’interiorità frustrata, ignorata e sofferente per il fatto di essere ai margini; la Brut Art si trasformò in messaggio liberatorio, senza regole, eseguito da persone ricoverate negli ospedali psichiatrici, dunque nata come terapia, e con il bisogno di far fuoriuscire con istintività e senza alcuna regola esecutiva, stilistica o formale per le quali non avevano alcuna base. Questo movimento artistico divenne tale grazie alla tenacia e all’intuizione di Jean Dubuffet che non solo ne fu massimo esponente ma collezionò anche un considerevole numero di opere eseguite da autori sconosciuti, che poi espose in una mostra per far conoscere quell’inedito modo di fare arte. Approccio che in qualche modo si concretizzò ed esaltò nel Graffitismo di Jean-Michel Basquiat la cui rabbia irrefrenabile si manifestava nelle sue grandi tele contraddistinte da un tratto stilizzato, graffiante e semplificato proprio per infondere intensità a un messaggio che doveva giungere senza alcun filtro.

Il medesimo approccio alla pittura impulsivo, così come la scelta del linguaggio esecutivo, contraddistingue l’artista romagnolo Widmer Tassinari in cui però non emerge la rabbia di Basquiat né l’approccio dissacrante e sarcastico di Bosch, piuttosto l’immediatezza tipica della Brut Art perché in lui ciò che è necessario è coltivare il proprio lato spontaneo, irrazionale, fanciullesco; di fatto la contestazione, l’emergenza di lasciar fuoriuscire qualcosa di trattenuto a lungo a livello sociale o mentale non appartengono più alla contemporaneità costituita essenzialmente dalla libertà di potersi esprimere senza alcuna catena o senza doversi uniformare a regole già sovvertite nel Novecento, almeno dal punto di vista creativo. Pertanto gli artisti attuali, e tra essi anche Tassinari, possono orientare la propria ricerca verso se stessi, verso la loro interiorità con cui portano alla luce le riflessioni più intime, quel lato spontaneo che riesce a trovare pienezza espressiva attraverso l’arte visiva.

La sua Brut Art diviene così un modo liberatorio per esprimere concetti spesso persino in contrasto con l’impatto visivo delle immagini, come se il gesto liberatorio della pittura fosse una connessione irrinunciabile tra i suoi pensieri più profondi, la sua visione delle cose, e l’anticonformismo formale che ha bisogno di manifestarsi solo secondo le regole dell’artista, non imposte dall’esterno bensì suggerite da un istinto creativo che ha bisogno di semplificare la realtà osservata, perché solo così è sicuro di non lasciare indietro alcun frammento di emozione.

Il tratto grafico è costantemente presente, a volte più evidente altre, soprattutto nelle opere più tendenti all’Astrattismo, più nascosto ma tuttavia essenziale per dare una traccia di quel pensiero, di quel concetto che poi trova il suo chiarimento nel titolo, di fatto complemento stesso dell’immagine impressa sulla tela.

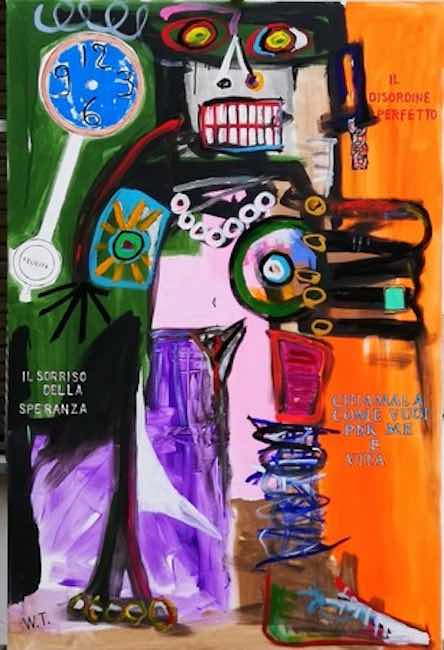

L’opera Il disordine perfetto sembra essere il simbolo di tutto ciò che rende possibile per Tassinari raggiungere la felicità, quella fatta di piccole cose, dei piaceri semplici che come tessere di un mosaico vanno a comporre l’insieme dell’appagamento proprio perché assecondati alla sua personalità; l’invito è quello di non lasciarsi appiattire dalla società e da regole che troppo spesso non corrispondono alle esigenze del singolo, di mostrare i propri veri colori senza timore del giudizio o di essere osservati con diffidenza solo perché capaci di ascoltare un’essenza frequentemente lasciata da parte in favore del bisogno di conformarsi. L’appartenenza alla Brut Art è evidente attraverso i tratti stilizzati, tipici del Primitivismo, che emergono dalla figurazione e che si espandono alla personalizzazione degli elementi fondamentali per l’artista la cui regola è quella di non avere regole.

E in effetti nel lavoro Parla l’interiorità Tassinari racconta il suo mondo più intimo in maniera indefinita, avvicinandosi a un Astrattismo da cui in ogni caso emerge una leggera figurazione che ricorda uno specchio, quasi come se l’artista suggerisse che è necessario restare soli, faccia a faccia con se stessi, per riuscire a sentire quella voce sottile abitualmente soffocata dall’urgenza di inseguire obiettivi utopici, persino talvolta in contrasto con la propria vera natura. La gamma cromatica è variopinta, così come lo è il ventaglio di emozioni che compongono e costruiscono la struttura dell’individuo, e che devono essere osservate e comprese nella loro eterogeneità e nel loro accostarsi in maniera confusa e caotica poiché non è possibile mettere in ordine ciò che non può essere razionalizzato.

E in Quando la magia della follia grida… tango!!, in cui il tratto grafico fuoriesce evidente quasi a essere prevalente sul cromatismo, Widmer Tassinari esprime ancora una volta l’ebrezza dell’essere liberi di lasciarsi andare senza freni, senza timori di uscire dagli schemi, sperimentando il piacere di danzare al proprio ritmo. È questa la metafora del ballo rappresentato nella tela, quell’essere in grado di andare avanti secondo le proprie regole e sulla base del proprio punto di vista, anche se considerato eccentrico e fuori dal comune, fino al momento in cui si incontrerà qualcuno che avrà lo stesso passo e a quel punto sarà raggiunta la gioia di poter essere folli in due. L’essenzialità di questa tela è funzionale a mettere in risalto le personalità dei protagonisti, come se il loro essersi incontrati dopo una lunga attesa costituisse il fulcro di un fermo immagine emozionale che mette le loro due essenze al centro della scena.

Widmer Tassinari ha un carattere eclettico e sperimentatore che lo conduce a scrivere poesie e a comporre canzoni, a cimentarsi persino con il mondo della moda associando la sua arte a una collezione presentata durante la sfilata di Pret à porter a Milano nel 2010. Ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a numerose fiere nazionali e internazionali, dove ha sempre raccolto consensi da parte del pubblico e degli addetti ai lavori, e le sue opere sono inserite nei più importanti cataloghi e riviste d’arte nazionali e internazionali.

WIDMER TASSINARI-CONTATTI

Email: widmer.tassinari@gmail.com

Sito web: http://www.widmertassinariopere.altervista.org/widmertassinari/widmer_tassinari.html

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/widmer.tassinari.9

The liberation of the unconscious and the nourishment of madness in Widmer Tassinari’s Brut Art

Being outside the box has distinguished a considerable number of artists since antiquity because their genius and ability to create something new, contrary even to the conventions and stylistic rules of their time, was concretised precisely in that taking a previously untrodden path, that freedom imposed on themselves of wanting to follow only and uniquely their expressive instincts that did not conform to the historical moment in which they lived. Similarly, in today’s art scene, are emerging artistic figures who escape the rules, create their own and let their essence flow out instinctively, communicating to the outside world what often cannot be explained in any other medium than painting. Today’s protagonist belongs to this creative group.

Already in the Netherlands of the Flemish period, therefore towards the end of the 15th century, a courageous artist, a voice out of the chorus, began to lay the foundations for what was seen and then picked up as the anticipation of non-conformism, of the ability to indulge one’s own nature even where it was considered crazy, scandalous, irreverent; Hieronymus Bosch, this is the name of the anticipatory genius of Surrealism, used an unconventional but innovative style to sarcastically describe the relationship between human beings and the impositions of religion, which were very strong at the time, and which were a source of frustration without actually being a deterrent to behaviour that was secretly enacted. The same themes, amplified but also extended to other areas by exalting madness as a way of being that no longer had to meet with judgement and opposition simply because it was far from the rules and commonplaces, were embraced by Surrealism where instincts and drives also joined the world of the unconscious, highlighting everything that was normally curbed by reason. Salvador Dali was a rebel but above all a free spirit who, both in art and in life, chose to live by his own rules, thus recounting in his canvases murky, impossible worlds in which sexuality and time returned obsessively as protagonists; just as improbable were the buildings and landscapes created by Maurits Cornelis Escher whose perspective confused the eye and at the same time attracted with that inexplicable mystery of how a mind could manage to conceive something so bizarre and unreal. We would then have to wait until the 1950s to be faced with a sort of synthesis between the executive confusion of the precursor Bosch and the liberation of a frustrated interiority, ignored and suffering from being on the margins; Brut Art became a liberating message, without rules, executed by people admitted to psychiatric hospitals, thus born as therapy, and with the need to instinctively let out the works of art without any executive, stylistic or formal rules for which they had no basis.

This artistic movement became such thanks to the tenacity and intuition of Jean Dubuffet, who was not only its greatest exponent, but also collected a considerable number of artworks by unknown artists, which he then showed in an exhibition to make known this unprecedented way of making art. An approach that somehow materialised and exalted in the Graffitism of Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose irrepressible rage was manifested in his large canvases characterised by a stylised, scratched and simplified stroke precisely to infuse intensity into a message that had to be conveyed without any filter. The same impulsive approach to painting, as well as the choice of executive language, distinguishes the Romagna artist Widmer Tassinari, in whom, however, neither the anger of Basquiat nor the desecrating and sarcastic approach of Bosch emerges, but rather the immediacy typical of Brut Art, because in him what is necessary is to cultivate his spontaneous, irrational, childlike side; in fact, the contestation, the emergence of letting out something held back for a long time socially or mentally no longer belongs to the contemporary world made up essentially of the freedom of being able to express oneself without any chains or without having to conform to rules already subverted in the 20th century, at least from a creative point of view. Therefore today’s artists, including Tassinari, can direct their research towards themselves, towards their interiority with which they bring to light their most intimate reflections, that spontaneous side that manages to find expressive fullness through visual art. His Brut Art thus becomes a liberating way of expressing concepts that are often even at odds with the visual impact of the images, as if the liberating gesture of painting were an inescapable connection between his deepest thoughts, his vision of things, and the formal non-conformism that needs to manifest itself only according to the artist’s rules, not imposed from the outside but suggested by a creative instinct that needs to simplify the reality observed, because only in this way is it certain not to leave behind any fragment of emotion.

The graphic line is constantly present, sometimes more evident others, especially in the paintings that tend more towards Abstractionism, more hidden but nevertheless essential to give a trace of that thought, that concept that then finds its clarification in the title, in fact the very complement of the image impressed on the canvas. The artwork The Perfect Disorder seems to be the symbol of everything that makes it possible for Tassinari to achieve happiness, that made up of small things, of simple pleasures that, like pieces of a mosaic, go to make up the whole of fulfilment precisely because they are in keeping with his personality; the invitation is to not let oneself be flattened by society and by rules that too often do not correspond to the needs of the individual, to show one’s true colours without fear of judgement or to be observed with diffidence just because one is able to listen to an essence frequently left aside in favour of the need to conform. The belonging to Brut Art is evident through the stylised traits, typical of Primitivism, that emerge from the figuration and expand to the personalisation of the fundamental elements for the artist whose rule is to have no rules. And indeed, in the painting Speaks the interiority Tassinari narrates his most intimate world in an indefinite manner, approaching an Abstractionism from which in each case emerges a light figuration reminiscent of a mirror, almost as if the artist were suggesting that it is necessary to be alone, face to face with oneself, in order to be able to hear that subtle voice habitually stifled by the urgency of pursuing utopian goals, even sometimes in contrast with one’s true nature.

The colour palette is colourful, as is the range of emotions that make up and build the structure of the individual, and which must be observed and understood in their heterogeneity and in their confused and chaotic juxtaposition, since it is not possible to put in order what cannot be rationalised. And in When the magic of madness cries… tango!!, in which the graphic line emerges clearly almost to the point of prevailing over the chromaticism, Widmer Tassinari once again expresses the thrill of being free to let oneself go without restraint, without fear of breaking the mould, experiencing the pleasure of dancing to one’s own rhythm. This is the metaphor of the dance depicted in the canvas, that of being able to go ahead according to one’s own rules and on the basis of one’s own point of view, even if considered eccentric and out of the ordinary, until the moment when one meets someone who has the same step, and at that point the joy of being able to be crazy in two is achieved. The essentiality of this canvas is functional in highlighting the personalities of the protagonists, as if their having met after a long wait constitutes the fulcrum of an emotional freeze frame that puts their two essences centre stage. Widmer Tassinari has an eclectic and experimental character that leads him to write poetry and compose songs, to even venture into the world of fashion, associating his art with a collection presented during the Pret à porter fashion show in Milan in 2010. He has taken part in numerous national and international fairs, where he has always received acclaim from the public and the art world, and his artworks are included in the most important national and international art catalogues and magazines.