Il corso della storia dell’arte contemporanea mostra un’incredibile poliedricità espressiva, una libertà da parte degli interpreti del panorama creativo attuale che forse difficilmente in passato avevano avuto poiché è esattamente grazie all’eredità precedente, a tutte le scoperte stilistiche e le sperimentazioni che hanno contraddistinto i secoli più recenti, che è possibile mescolare, fondere, reinterpretare le linee guida spesso rigorosamente separate alla loro nascita. Dunque quest’attitudine alla libertà interpretativa permette agli artisti di lasciare che la pittura o la scultura divengano spontaneamente estensione della propria interiorità, del proprio modo di osservare e di comprendere tutto ciò che li circonda. Il protagonista di oggi ha un approccio morbido alla realtà dalla quale non può staccarsi dunque è da essa che parte per poi avvolgere le atmosfere narrate di un tocco poetico e delicato, quasi volesse sottolineare quanto in fondo ogni circostanza, ogni immagine, faccia indelebilmente parte della dimensione emotiva di ciascuno.

Nel corso di tutto il Diciannovesimo secolo, fatta eccezione per gli ultimi anni di avvicinamento al Novecento, l’arte era ancora considerata solo ed esclusivamente figurativa, una manifestazione dell’equilibrio tra estetica e abilità esecutiva dei maestri che si attenevano alle regole accademiche sulla migliore resa del colore, della prospettiva, del chiaroscuro e dell’utilizzo della luce. In tutta questa perfezione esecutiva rimaneva un po’ in secondo piano quella che era l’emozione, l’ascolto di un’interiorità che non trovava spazio all’interno di quella formale manifestazione creativa; l’unica eccezione fu costituita dal Romanticismo, un movimento che si estese in tutta Europa e che diede spazio alla poesia, alle sensazioni travolgenti che dagli esecutori delle opere giungevano fino all’osservatore con tutta la loro forza espressiva. Dagli Stati Uniti fino al territorio Russo, il movimento permise ad artisti sensibili quanto talentuosi di rappresentare tutta la forza della natura in relazione con l’essere umano che di fronte a tanta maestosità non poteva che sentirsi piccolo, effimero, ridimensionato; da William Turner a Ivan Ajvazovskij, da Thomas Cole a John Constable, da Caspar David Friedrich a Johan Christian Dahl, tutti furono in grado di evidenziare il legame sottile e indissolubile tra l’uomo e la natura intorno a sé, ma anche le energie che dalle forze naturali si sprigionano e che raggiungono l’individuo inducendolo alla riflessione e all’autoconsapevolezza delle proprie fragilità e incertezze. Il declino dell’Arte Romantica coincise con l’avvento del Positivismo, un periodo filosofico che mostrava interesse per l’analisi scientifica della realtà e che artisticamente si tradusse con l’affermarsi del Realismo, un movimento pittorico interessato a evidenziare la realtà dei lavoratori, la disparità delle classi sociali, oppure la rappresentazione dei paesaggi nella loro incontaminata bellezza, come nel caso della Scuola di Barbizon, in Francia, i cui rappresentanti volevano cogliere la vita rurale delle persone ritratte, la semplicità e la naturalezza con cui affrontavano la loro quotidianità. Uno dei più grandi esponenti di questa scuola fu Jean-François Millet che affiancò in prestigio i maggiori esponenti del Realismo europeo come Gustave Courbet e Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo. L’attenzione all’essere umano cominciò dunque a essere il tema dominante dell’arte di fine Ottocento, preparando il terreno ai successivi movimenti pittorici del nuovo secolo che misero l’interiorità e l’emozione al centro della narrazione.

L’artista polacco Dariusz Dębski sintetizza, colma la distanza tra i due movimenti ottocenteschi scegliendo uno stile tradizionale, attento a tutte le regole coloristiche e di preparazione della tela attraverso il disegno, la perfetta resa della prospettiva e della profondità, mostrando però non solo il desiderio di riprodurre l’osservato nella sua forma più veritiera, bensì lasciando che tutte le sensazioni provate nell’atto del dipingere o emanate dai personaggi e dai paesaggi che sceglie di immortalare fuoriescano in maniera spontanea e lirica, con la caratteristica di quell’ascolto sottile che aveva contraddistinto il Romanticismo in tutte le sue declinazioni. La gamma cromatica delle sue opere si adegua al sentire, all’interiorità di Dębski nel momento in cui si è avvicinato alla tela cominciando il percorso di creazione; dunque spesso i suoi paesaggi mostrano quel sublime che tanto aveva contraddistinto Turner e Ajvazovskij, quelle travolgenti sensazioni che avvolgono l’individuo ogni qualvolta si trova davanti alla maestosità della natura, alla sua forza in grado di ridimensionare qualsiasi presunzione e mania di grandezza dell’essere umano nel tentare di dominarla.

Nel momento in cui, invece, Dariusz Dębski rivolge l’attenzione alle persone, agli animali, a tutto ciò che appartiene al suo quotidiano, la luce predomina, le tonalità divengono più vivaci, chiare e luminose, quasi riuscisse a creare una connessione empatica profonda con i soggetti che sceglie di rendere protagonisti; il tratto realista lo induce a porre attenzione a tutti i dettagli, a delineare con meticolosità il passaggio tra luci e ombre, come se senza di essi si perdesse quel senso della realtà a cui lui sceglie di appartenere. La narrazione che emerge è priva di giudizio, senza alcun tipo di riflessione personale, bensì ciò che contraddistingue la sua pittura è quella di lasciar parlare le sensazioni dei suoi personaggi, divenendo di fatto interprete per immagini di ciò che gli istanti colti suggeriscono nella loro spontanea inconsapevolezza.

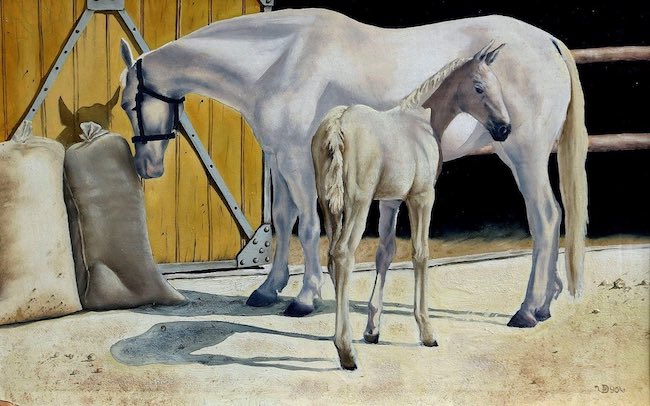

Nella tela Cavalla con puledro questo orientamento rappresentativo di Dariusz Dębski fuoriesce in modo chiaro, la pura bellezza dell’animale che si prende cura del suo piccolo sembra aver conquistato lo sguardo sensibile dell’artista che ha così deciso di rendere eterno il frangente osservato; i colori sono perfettamente fedeli alla realtà ma sono soprattutto le ombre a rendere più vera la composizione, lasciando all’osservatore il compito di immaginare tutto il resto del mondo intorno a quella poetica scena.

Anche gli oggetti divengono talvolta il centro dell’attenzione di Dębski, proprio in virtù del senso di familiarità che suscitano, quella certezza spesso ignorata proprio perché sempre davanti allo sguardo all’interno delle case e dunque ormai parte del proprio campo visivo al punto di non essere più in grado di vederle; è questo lo spirito con cui ha dipinto la tela Natura morta, rendendo protagonisti una teiera, una bottiglia d’acqua, un pomodoro, quasi dall’altra parte della scena si stesse svolgendo un pranzo di famiglia per cui quegli oggetti sono fondamentali. Qui i colori sono molto accesi, vivaci, perché in fondo è questa la sensazione che si prova nei momenti di condivisione con le persone che si amano, dove tutto è semplice, spontaneo, senza filtri e senza autodifese, solo un istante di esistenza.

Nelle vedute cittadine Darius Dębski mette in evidenza la geometricità dei palazzi, come nel dipinto Venezia, piscina de Frezzaria

in cui racconta uno scorcio della meravigliosa città lagunare che sembra essersi messa in posa con tutta la bellezza che la contraddistingue e che non smette di affascinare turisti di ogni parte del mondo. Il tratto pittorico è incredibilmente realista in questo dipinto, e i tipici colori degli edifici veneziani sono amplificati dalla presenza del buio del cielo e delle acque, mosse solo da una leggera brezza e illuminate dal riflesso dell’unica lampada accesa; eppure, nonostante la presenza di una sola fonte di luce, la composizione non è cupa, al contrario la città sembra risplendere autonomamente attraverso il Realismo Romantico di Dębski.

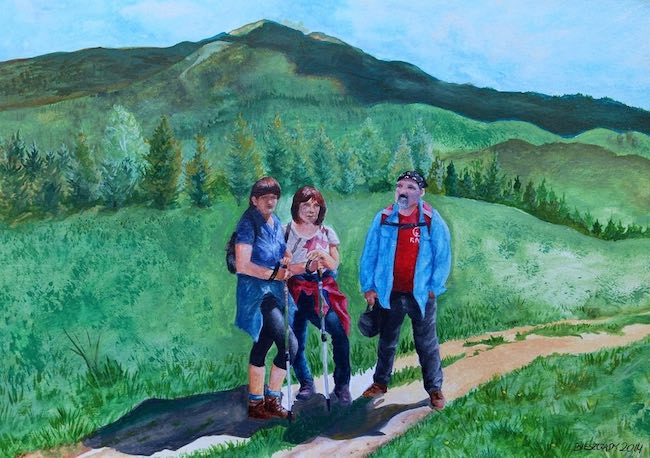

L’olio su tela o su tavola è la tecnica che lo contraddistingue ma si misura anche con l’acquarello che gli permette di avere una maggiore velocità di esecuzione; è proprio questa la tecnica scelta per l’opera Sentiero di Bieszczady, una località montana polacca dove ama fare passeggiate e cogliere attimi che colpiscono la sua sensibile attenzione fino a desiderare di riprodurli; qui sembra di respirare l’aria di montagna, di cogliere il senso di rilassamento dei tre protagonisti in posa e consapevoli di diventare attori principali per il breve tempo della realizzazione di un’opera. L’acquarello è utilizzato in modo molto denso, sembra quasi simile all’acrilico perché l’artista non vuole rinunciare all’intensità dell’esistenza, ai colori forti e pieni che costituiscono la metafora della capacità di assaporare ogni istante che la vita dona; dunque il verde è particolarmente brillante, tanto quanto l’azzurro del cielo è morbido e sfumato, compagno di viaggio dei personaggi.

Dariusz Dębski ha mosso i primi passi nell’arte da bambino ma poi le scelte di vita e professionali lo hanno condotto verso un percorso differente durante il quale però non ha mai dimenticato il suo primo amore, quello per la pittura; non appena ha potuto ritirarsi dal lavoro ha deciso di dedicarsi a tempo pieno a dipingere, iniziando anche a seguire dei corsi a Varsavia, subito abbandonati perché gli schemi e le regole esecutive gli avrebbero fatto perdere quell’autonomia espressiva che da sempre lo contraddistingue. Attualmente è apprezzato in tutto il mondo, in particolar modo negli Stati Uniti paese da cui riceve molte commissioni.

DARIUS DĘBSKI-CONTATTI

Email: ramones1@vp.pl

Facebook: www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100014348743970

The gaze over the world of Dariusz Dębski, when Realism meets Romanticism

The course of contemporary art history shows an incredible versatility of expression, a freedom of the interpreters of today’s creative scene that they perhaps hardly had in the past, since it is precisely thanks to the previous inheritance, to all the stylistic discoveries and experiments that have characterised the most recent centuries, that it is possible to mix, blend and reinterpret the guidelines that were often strictly separated at their birth. Thus, this attitude of interpretative freedom allows artists to let painting or sculpture spontaneously become an extension of their own interiority, of their own way of observing and understanding everything that surrounds them. Today’s protagonist has a soft approach to reality from which he cannot detach himself, so it is from this that he starts out and then envelops the narrated atmospheres with a poetic and delicate touch, almost as if he wanted to emphasise how fundamentally each circumstance, each image, is indelibly part of the emotional dimension of each person.

Throughout the entire 19th century, with the exception of the final years of the 20th century, art was still considered solely and exclusively figurative, a manifestation of the balance between aesthetics and executional skill of the masters who adhered to academic rules on the best rendering of colour, perspective, chiaroscuro and the use of light. The only exception was Romanticism, a movement that spread throughout Europe and gave space to poetry, to the overwhelming sensations that from the executors of the artworks reached the observer with all their expressive force. From the United States to the Russian territory, the movement allowed sensitive and talented artists to represent all the power of nature in relation to the human being who, in front of such majesty, could only feel small, ephemeral, reduced in size; from William Turner to Ivan Ajvazovskij, from Thomas Cole to John Constable, from Caspar David Friedrich to Johan Christian Dahl, all were able to highlight the subtle and indissoluble bond between man and nature around him, but also the energies that emanate from natural forces and reach the individual, inducing him to reflection and self-awareness of his own frailties and uncertainties. The decline of Romantic Art coincided with the advent of Positivism, a philosophical period that showed an interest in the scientific analysis of reality and that artistically resulted in the rise of Realism, a pictorial movement interested in highlighting the reality of the working people, the inequality of social classes, or the depiction of landscapes in their pristine beauty, as in the case of the School of Barbizon, in France, whose representatives wanted to capture the rural life of the people portrayed, the simplicity and naturalness with which they coped with their everyday life. One of the greatest exponents of this school was Jean-François Millet, who joined in prestige the leading exponents of European Realism such as Gustave Courbet and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo.

Attention to the human being thus began to be the dominant theme of late 19th century art, paving the way for the subsequent pictorial movements of the new century that placed interiority and emotion at the centre of the narrative. The Polish artist Dariusz Dębski synthesises, bridges the gap between the two 19th century movements by choosing a traditional style, attentive to all the rules of colour and preparation of the canvas through drawing, the perfect rendering of perspective and depth, while showing not only a desire to reproduce the observed in its most truthful form, but rather allowing all the sensations felt in the act of painting or emanating from the characters and landscapes he chooses to immortalise to come forth in a spontaneous and lyrical manner, with the characteristic subtle listening that had distinguished Romanticism in all its declinations. The chromatic range of his artworks adapts to Dębski‘s feelings, to his interiority at the moment he approached the canvas, beginning his path of creation; thus, his landscapes often display that sublime that had so distinguished Turner and Ajvazovskij, those overwhelming sensations that envelop the individual whenever he finds himself before the majesty of nature, its power capable of redefining any presumption and mania for greatness of the human being in attempting to dominate it. When, on the other hand, Dariusz Dębski turns his attention to people, animals, to everything that belongs to his everyday life, light predominates, the tones become brighter, clear and luminous, almost as if he were able to create a deep empathic connection with the subjects he chooses to make protagonists; the realist stroke induces him to pay attention to all the details, to meticulously delineate the transition between light and shadow, as if without them one would lose that sense of reality to which he chooses to belong. The narrative that emerges is devoid of judgement, without any kind of personal reflection; rather, what distinguishes his painting is that of letting the sensations of his characters speak, becoming in fact the interpreter through images of what the captured moments suggest in their spontaneous unconsciousness. In the painting Mare with foal, this representational orientation of Dariusz Dębski emerges clearly, the pure beauty of the animal caring for its young seems to have conquered the sensitive gaze of the artist, who has thus decided to make the observed event eternal; the colours are perfectly faithful to reality, but it is above all the shadows that make the composition truer, leaving the observer to imagine the rest of the world around that poetic scene. Objects, too, sometimes become the focus of Dębski‘s attention, precisely because of the sense of familiarity they arouse, that certainty often ignored precisely because they are always in front of one’s gaze inside the home and therefore now part of one’s field of vision to the point of no longer being able to see them; this is the spirit with which he has painted the Still Life canvas, making a teapot, a bottle of water, a tomato the protagonists, almost as if a family lunch were taking place on the other side of the scene for which those objects are fundamental. Here the colours are very bright, vivid, because after all this is the feeling one gets when sharing with loved ones, where everything is simple, spontaneous, without filters or self-defence, just an instant of existence.

In his views of the city, Darius Dębski emphasises the geometric nature of the buildings, as in the painting Venice, piscina de Frezzaria in which he depicts a glimpse of the marvellous lagoon city that seems to have posed with all its beauty and that never ceases to fascinate tourists from all over the world. The pictorial line is incredibly realistic in this painting, and the typical colours of Venetian buildings are amplified by the presence of the dark sky and waters, moved only by a light breeze and illuminated by the reflection of the only lighted lamp; and yet, despite the presence of a single light source, the composition is not gloomy; on the contrary, the city seems to shine on its own through Dębski‘s Romantic Realism. Oil on canvas or panel is his signature technique, but he also measures himself with watercolour, which allows him a greater speed of execution; this is precisely the technique chosen for the artwork Path of Bieszczady, a Polish mountain resort where he loves to take walks and capture moments that strike his sensitive attention to the point of wanting to reproduce them; here one seems to breathe in the mountain air, to grasp the sense of relaxation of the three protagonists posing and aware of becoming the main actors for the brief time of the artwork’s creation.

The watercolour is used in a very dense way, it almost seems similar to acrylic because the artist does not want to renounce the intensity of existence, the strong, full colours that are a metaphor for the ability to savour every moment that life bestows; therefore the green is particularly bright, as much as the blue of the sky is soft and nuanced, the characters’ travelling companion. Dariusz Dębski took his first steps in art as a child, but then his life and professional choices led him to a different path, during which he never forgot his first love, painting. As soon as he was able to retire from work, he decided to devote himself full-time to art, even starting to take courses in Warsaw, which he immediately abandoned because the schemes and rules of execution would have made him lose the expressive autonomy that has always distinguished him. He is currently appreciated in the whole world, especially in the United States from where he receives many commissions.