In un mondo contemporaneo in cui la bellezza e la perfezione sembrano essere imperativi irrinunciabili, rompere in maniera netta lo schema comune costituisce un approccio insolito ed evidentemente molto coraggioso, irriverente ma anche consapevole di sorprendere lo sguardo con un forte impatto che non può fare a meno di generare un sorriso e contemporaneamente una riflessione. Questo è il percorso artistico del protagonista di oggi in cui da un lato racconta le atmosfere sorridenti, spensierate e semplici di un periodo felice nella storia del secolo scorso in cui tutto spingeva verso l’ottimismo e la piacevolezza del vivere, dall’altro rientra in uno degli stili più underground che fonde il mondo dei fumetti e delle pubblicità in chiave inquietante o in alcuni casi comica.

La società statunitense della seconda metà del Novecento vide il nascere di mode e tendenze innovative e avanguardiste, soprattutto tra i giovani che avevano bisogno di appartenere a un gruppo specifico, di identificarsi in ideali al passo con i tempi; fu esattamente in quel periodo che nacque uno dei movimenti pittorici più insoliti, strani, al di fuori di ogni schema, che attingeva alle esperienze pittoriche precedenti attualizzandole alle tematiche affini a quei mondi nascenti. Il Low Brow o Pop Surrealismo, vide la sua nascita verso la fine degli anni Settanta del secolo più vivace della storia dell’arte, mostrando il suo forte legame con la cultura metropolitana e tutto ciò che si era affermato divenendo un punto fermo della cultura di quel periodo, come i fumetti, i cartoni animati, la pubblicità e la musica punk-underground, ma al contempo svelando un lato inquietante, dark, deformante che attingeva proprio al Surrealismo.

Proprio quest’ultimo movimento aveva destabilizzato i salotti culturali con le sue atmosfere che riconducevano agli incubi rappresentando mostri, forme antropomorfe e atmosfere apocalittiche, aprendo la strada alla possibilità di considerare l’arte non più come narrazione oggettiva della realtà, bensì come emanazione di un’interiorità incapace di oltrepassare i traumi emotivi ed esistenziali generati dalle guerre e dalle distruzioni dei primi decenni del secolo. Salvador Dalì e Max Ernst furono forse gli autori più inclini a soffermarsi su tutte le angosce della mente raffigurando scenari terrificanti e mostrando quanto anche la deformazione e la bruttezza potessero essere parte dell’espressività artistica. Terminato il periodo delle guerre emerse un nuovo ottimismo, una fiducia verso il futuro che permise la nascita di un nuovo modo di vivere e di pensare, una rilassatezza che si manifestò in ogni ambito quotidiano, così come una leggerezza dovuta a un inedito benessere economico che furono la base della Pop Art in cui i miti e i divi, oltre che ai beni di largo consumo divenuti simbolo della società, in particolar modo quella statunitense degli anni Cinquanta, trasformarono in arte anche il mondo dei fumetti, con Roy Lichtenstein, dei super eroi, con Steve Kaufman e, ovviamente delle celebrità cinematografiche con Andy Warhol.

Qualche decennio dopo alcuni artisti avvertirono l’esigenza di unire i due estremi, l’inquietante del Surrealismo con la leggerezza visiva della Pop Art, dando vita appunto al Pop Surrealismo in cui la realtà viene completamente stravolta, osservata attraverso il filtro destabilizzante dell’assurdo, di atmosfere gotiche e cupe, ma anche riproponendo il nuovo mondo dei fumetti dove i protagonisti non erano più personaggi perfetti, muscolosi e avvenenti bensì anche persone buffe, pasticcione dove l’estetica era messa in secondo piano rispetto al paradosso e all’irriverente di una società che stava compiendo un nuovo cambiamento. Mark Ryden si collocò tra gli autori più sconcertanti, rappresentando un mondo infantile crudele e angosciante nella sua apparente innocenza, mentre Marion Peckintrodusse la deformazione morfologica per entrare in maniera più visibile nell’universo dell’assurdo.

L’artista di origine canadese Nathan James, da molti anni residente a Londra, approccia il Pop Surrealismo in maniera più Pop e meno surrealista, ispirandosi ai fumetti più noti degli ultimi anni, i Simpson, a cui attinge per ironizzare sui tratti somatici delle sue protagoniste criticando con leggerezza una società attuale che evoca sì il bisogno dell’inclusione, ma poi in realtà continua a proporre modelli di bellezza irraggiungibile che lasciano ai margini chi non vi corrisponde.

La figurazione dunque è fumettistica, anche l’utilizzo dei colori e la narrazione appartengono al mondo dei cartoni animati, stimolando la riflessione esistenzialista attraverso la semplicità e l’immediatezza visiva; i corpi delle sue protagoniste, così come le ambientazioni e l’abbigliamento, sono ispirati alle pin up degli anni Cinquanta, dunque morbidi ed esteticamente armoniosi, così come il loro abbigliamento, ma poi i volti rompono l’equilibrio con la loro deformata bruttezza, con gli occhi divergenti, stralunati, strabici, e le bocche con denti orribili. Eppure non perdono la sicurezza in se stesse, non sembrano curarsi dei loro macroscopici difetti, quasi Nathan James volesse prendersi gioco della superficialità attuale evidenziando quanto essa possa nascondere un’essenza ben diversa dall’apparenza, oppure al contrario, volesse sottolineare l’importanza dell’autostima in un mondo in cui l’essere umano sembra dipendere dall’approvazione esterna.

In qualche modo questo, ancora una volta, riconduce verso gli anni Cinquanta, quando la cura del proprio aspetto non era privata dei valori e della sostanza come invece sta avvenendo nella contemporaneità, non c’era la ricerca della perfezione a ogni costo, piuttosto si cercava di ottenere il meglio rispettando ciò che si era, all’esterno e all’interno, risultando così persone con uno spessore maggiore e più solido.

In Down by the bay l’artista ritrae una donna nella tipica posa femminile della metà del secolo scorso, la figura è flessuosa, elegante, da femme fatale, certa che tutto il mondo maschile, passando, non potrà fare a meno di rivolgerle uno sguardo. L’insenatura dietro di lei contribuisce a rendere armonico e romantico lo sfondo, leggermente sfocato perché a emergere deve essere la figura in primo piano; quando però lo sguardo va verso il volto ecco che si compie la rottura, il rumore stridente del gesso sulla lavanga, poiché l’occhio trova davanti a sé l’innegabile bruttezza disarmonica della ragazza il cui sorriso sembra più una smorfia, i cui occhi sono incredibilmente rotondi, esattamente come quelli dei Simpson, e come se non bastasse completamente strabici. Lei però non se ne cura e procede nella sua vita con la stessa sicurezza delle altre più avvenenti, quasi Nathan James volesse suggerire che la bellezza è uno stato d’animo interiore, un modo di sentirsi che induce gli altri a ad andare oltre lasciandosi catturare più dall’energia che si emana che non dall’aspetto oggettivo.

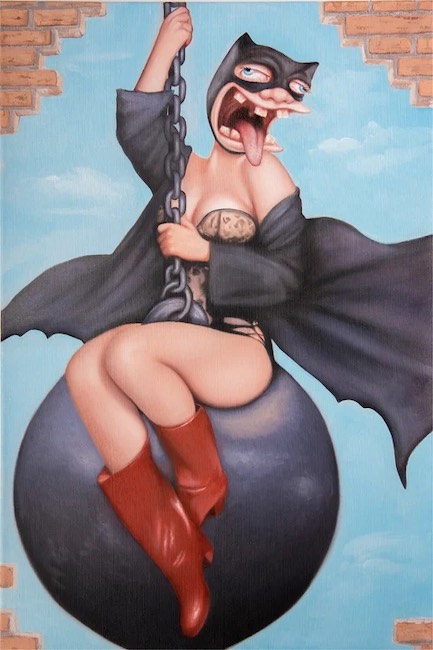

In Batshit Crazy invece emerge tutto il lato irriverente e impertinente dell’autore che fa una caricatura a una super eroina, Batgirl, svelandone un tipo di personalità non appartenente al personaggio originario, seria e supporto per Batman nel combattere il crimine; qui al contrario la ragazza sembra prendere in giro il mondo intero con il suo atteggiamento irrispettoso e provocatorio, quasi, nella consapevolezza dell’attrazione verso l’estetica della società moderna, volesse invitare tutti a guardare e ammirare anche la sua assoluta non perfezione, quella deformità che lei si butta alle spalle mettendo in evidenza i suoi punti forti come il fisico decisamente avvenente, il coraggio di mostrarsi in lingerie, la forza di saltare e di tenersi appesa a una sfera di piombo. Questo dipinto è decisamente fumettistico, forse perché è il tipo di approccio più affine all’ironia di Nathan James che osserva in modo sagace tutto ciò che gli sta intorno e poi rilascia i suoi pensieri con uno stile che non induce il fruitore a mettersi sulla difensiva, bensì lo spinge ad avvicinarsi in modo aperto alla giocosità attraverso cui l’autore lascia filtrare il suo punto di vista.

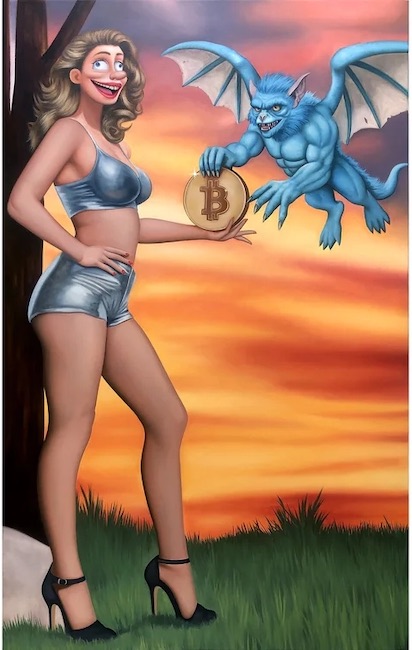

In The past gives away the future l’artista affronta un tema molto contemporaneo, quello della moneta digitale che sembra essere sul punto di diventare il futuro, il modo per aggirare il potere egemonico delle banche permettendo all’individuo di crearsi una ricchezza parallela che tuttavia è effimera, può essere cancellata con un semplice click su un pulsante. Ecco perché il mostro con le ali che afferra la moneta e che rappresenta il futuro, ha un aspetto inquietante e demoniaco, quasi nascondesse un secondo fine, un rischio che la donna non riesce a fiutare, fidandosi senza riserve di quella nuova opportunità. La domanda che viene sollevata è dunque quasi esistenziale poiché l’osservatore è stimolato a riflettere su quanto le innovazioni possano essere davvero un’opportunità oppure costituire un’incognita da cui doversi tutelare fermando però così le aperture che potrebbero generarsi.

Nathan James ha al suo attivo mostre personali a Toronto, Los Angeles, Londra, Taipei e Lussemburgo, la partecipazione a collettive e fiere d’arte negli USA, in Canada, Italia, Regno Unito, Australia, Belgio e Germania e le sue opere fanno parte di importanti collezioni private.

NATHAN JAMES-CONTATTI

Email: nathan@nathanjamespaintings.com

Sito web: www.nathanjamespaintings.com/

Instagram: www.instagram.com/nathanjamespaintings/

Nathan James’ Pop Surrealism, between nostalgia for the 1950s and the irony of exploring ugliness

In a contemporary world where beauty and perfection seem to be essential imperatives, breaking sharply with the common pattern is an unusual and clearly very courageous approach, irreverent but also aware of surprising the viewer with a strong impact that cannot help but generate a smile and, at the same time, reflection. This is the artistic path of today’s protagonist, who on the one hand recounts the smiling, carefree, and simple atmospheres of a happy period in the history of the last century when everything pushed towards optimism and the pleasure of living, and on the other hand is part of one of the most underground styles that blends the world of comics and advertising in a disturbing or, in some cases, comical way.

American society in the second half of the 20th century saw the emergence of innovative and avant-garde fashions and trends, especially among young people who needed to belong to a specific group and identify with ideals in step with the times; it was precisely during this period that was born one of the most unusual, strange, and unconventional painting movements, drawing on previous pictorial experiences and updating them with themes related to those emerging worlds. Low Brow or Pop Surrealism emerged in the late 1970s of one of the most vibrant period in art history, demonstrating its strong connection with metropolitan culture and everything that had become established as a staple of the culture of that period, such as comics, cartoons, advertising, and punk-underground music, but at the same time revealing a disturbing, dark, deforming side that drew precisely on Surrealism.

It was this latter movement that had destabilized cultural salons with its atmospheres reminiscent of nightmares, representing monsters, anthropomorphic forms, and apocalyptic atmospheres, paving the way for the possibility of considering art no longer as an objective narration of reality, but as an emanation of an inner self unable to overcome the emotional and existential traumas generated by the wars and destruction of the early decades of the century. Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst were perhaps the artists most inclined to dwell on all the anxieties of the mind, depicting terrifying scenarios and showing how even deformation and ugliness could be part of artistic expression. After the wars emerged a new optimism, a confidence in the future that allowed the birth of a new way of living and thinking, a relaxed attitude that manifested itself in every aspect of daily life, as well as a lightness due to unprecedented economic prosperity, which formed the basis of Pop Art where myths and celebrities, as well as consumer goods that had become symbols of society, particularly in the United States in the 1950s, transformed into art the world of comics with Roy Lichtenstein, the superheroes with Steve Kaufman, and, of course, the movie stars with Andy Warhol.

A few decades later, some artists felt the need to combine the two extremes, the disturbing nature of Surrealism with the visual lightness of Pop Art, giving rise to Pop Surrealism, in which reality is completely distorted, observed through the destabilizing filter of the absurd, of gothic and gloomy atmospheres, but also by reintroducing the new world of comics where the protagonists were no longer perfect, muscular, and attractive characters, but also funny, clumsy people where aesthetics took a back seat to the paradox and irreverence of a society that was undergoing a new change. Mark Ryden was one of the most disconcerting authors, depicting a cruel and distressing childhood world in its apparent innocence, while Marion Peck introduced morphological deformation to enter the universe of the absurd in a more visible way. Canadian-born artist Nathan James, a long-time resident of London, approaches Pop Surrealism in a more Pop and less surrealist way, drawing inspiration from the most famous comics of recent years, The Simpsons, which he uses to ironize the physical features of his protagonists, lightly criticizing a society that evokes the need for inclusion, but in reality continues to propose unattainable models of beauty that marginalize those who do not correspond to them.

The figuration is therefore cartoonish, and even the use of colors and narration belong to the world of cartoons, stimulating existentialist reflection through simplicity and visual immediacy; the bodies of his protagonists, as well as the settings and clothing, are inspired by 1950s pin-ups, and are therefore soft and aesthetically harmonious, as is their clothing, but then their faces break the balance with their deformed ugliness, with divergent, wild-eyed, cross-eyed eyes and mouths with horrible teeth. Yet they do not lose their self-confidence, they do not seem to care about their macroscopic defects, as if Nathan James wanted to mock current superficiality by highlighting how it can hide an essence very different from appearance, or, on the contrary, wanted to emphasize the importance of self-esteem in a world where human beings seem to depend on external approval. In some ways, this once again takes us back to the 1950s, when caring for one’s appearance was not deprived of values and substance as it is today, there was no quest for perfection at any cost, but rather a desire to achieve the best while respecting who one was, both externally and internally, thus resulting in people with greater depth and solidity. In Down by the Bay, the artist portrays a woman in a typical feminine pose from the middle of the last century, the figure is supple, elegant, femme fatale, certain that all the men passing by will not be able to help but glance at her. The inlet behind her contributes to the harmonious and romantic background, slightly blurred so that the figure in the foreground stands out; however, when the gaze moves to the face, there is a break, the jarring sound of chalk on a blackboard, as the eye is confronted with the undeniable, disharmonious ugliness of the girl, whose smile looks more like a grimace, whose eyes are incredibly round, just like those of the Simpsons, and, as if that weren’t enough, completely cross-eyed.

She, however, does not care and goes about her life with the same confidence as the more attractive ones, as if Nathan James wanted to suggest that beauty is an inner state of mind, a way of feeling that induces others to go beyond, allowing themselves to be captivated more by the energy she exudes than by her objective appearance. In Batshit Crazy, on the other hand, the author’s irreverent and impertinent side emerges, caricaturing a superheroine, Batgirl, revealing a personality type that does not belong to the original character, who is serious and supports Batman in fighting crime; here, on the contrary, the girl seems to be mocking the whole world with her disrespectful and provocative attitude, almost as if, aware of the attraction to the aesthetics of modern society, she wanted to invite everyone to look at and admire her absolute imperfection, that deformity that she throws behind her by highlighting her strengths, such as her decidedly attractive physique, her courage to show herself in lingerie, and the bravery to jump and hang from a lead ball. This painting is decidedly comic-like, perhaps because it is the type of approach most akin to the irony of Nathan James, who observes everything around him with sagacity and then releases his thoughts in a style that does not cause the viewer to become defensive, but rather pushes him to approach in an open way the playfulness through which the author lets his point of view filter through.

In The past gives away the future, the artist tackles a very contemporary theme, that of digital currency, which seems to be on the verge of becoming the future, a way to circumvent the hegemonic power of banks, allowing individuals to create a parallel wealth that is nevertheless ephemeral, as it can be wiped out with a simple click of a button. This is why the winged monster that grabs the coin and represents the future has a disturbing and demonic appearance, as if it were hiding an ulterior motive, a risk that the woman fails to sense, trusting unreservedly in this new opportunity. The question raised is therefore almost existential, as the observer is encouraged to reflect on whether innovations can truly be an opportunity or maybe they constitute an unknown factor from which one must protect oneself, thus blocking the openings that could be generated. Nathan James has had solo exhibitions in Toronto, Los Angeles, London, Taipei, and Luxembourg, has participated in group exhibitions and art fairs in the US, Canada, Italy, the UK, Australia, Belgium, and Germany and his artworks are part of important private collections.