La nascita del Surrealismo, agli inizi del Ventesimo secolo, trovò una perfetta sintesi tra la necessità di indagare l’incognito della psiche umana, approfondire le sue angosce, i fantasmi della mente che fuoriuscivano solo nella fase onirica, e quell’attitudine a mostrare il lato oscuro dell’animo umano, la parte nascosta e inconfessabile che solo alcuni artisti del passato avevano avuto il coraggio di mostrare nelle loro opere. Nel Cinquecento fu il fiammingo Hieronymus Bosch ad andare contro le linee guida espressive dell’epoca immaginando universi in cui tutti gli istinti umani, dove la ribellione spontanea alle rigide regole della morale e della chiesa, uscivano fuori in maniera sorprendente, inquietante, irrazionale; le sue ambientazioni prive di prospettiva e piene di personaggi e scenari frutto di visioni dell’autore, mostrarono quanto la pittura potesse essere non solo ritratto e descrizione reale bensì anche strumento per raccontare un’altra realtà, quella parallela che apparteneva all’interiorità di chiunque, pur rimanendo segretamente inconfessata. Sulla base dell’eccentrica visione espressiva di Bosch si svilupparono diversi secoli dopo, e precisamente nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento, le linee guida di alcuni degli autori più estremi del Simbolismo, come Félicien Rops che si concentrò prevalentemente sulla sfera sessuale più perversa, e Arnold Böcklin il quale invece focalizzò la propria produzione sull’esplorazione dell’aldilà e della sua manifestazione silenziosa nella realtà. Le esperienze pittoriche del Simbolismo, così come di Hieronymus Bosch, costituirono letteralmente le fondamenta del Surrealismo che, basandosi sulle teorie della psicanalisi elaborate da Sigmund Freud, voleva esplorare tutto ciò che si nascondeva al di sotto della facciata mostrata dagli individui, intendeva portare alla luce tutti quei fantasmi relegati in un angolo nascosto della mente che si liberavano durante la fase del sonno. Fu in particolare Salvador Dalì a lasciarsi ispirare dagli scenari di Bosch, così come dal forte legame con la sfera sessuale di Félicien Rops, ma molti altri autori appartenenti alla nuova corrente pittorica vollero invece spostarsi verso le riflessioni mentali, i paradossi ingannevoli in cui il mondo inconsapevolmente si muove, la necessità della società dell’epoca di uscire dall’ipocrisia e andare invece alla sostanza.

Questo tipo di atteggiamento narrativo contraddistinse il lavoro di René Magritte che in qualche modo cercò di avvicinarsi agli enigmi mai spiegati della Metafisica di Giorgio De Chirico pur perdendone la geometricità e il riferimento al Neoclassicismo. Voce fuori dal coro di quel periodo fu un altro autore che andò oltre ogni immaginabile rappresentando costruzioni senza senso dove i piani e gli spazi vivevano su una prospettiva improbabile; il lavoro di Mauritius Cornelius Escher stupì per la sua capacità di raccontare un mondo infinitamente possibile, mostrando all’uomo quanto tutto ciò che è logico e razionale possa essere semplicemente controvertito attraverso la rottura di uno schema predefinito rendendo tutto realizzabile. L’artista statunitense Issy Wood, da molti anni residente a Londra, riattualizza le esperienze degli autori e dei movimenti citati sinora alla poetica espressiva contemporanea, compiendo un’analisi attenta e senza filtri dei modi di vivere e di relazionarsi che imperano in un presente essenzialmente consumistico, dove ciò che l’individuo è sembra corrispondere a ciò che possiede o che è in grado di acquistare.

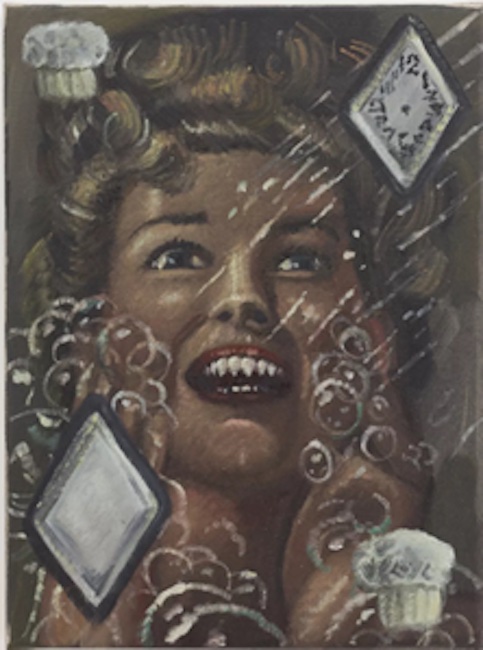

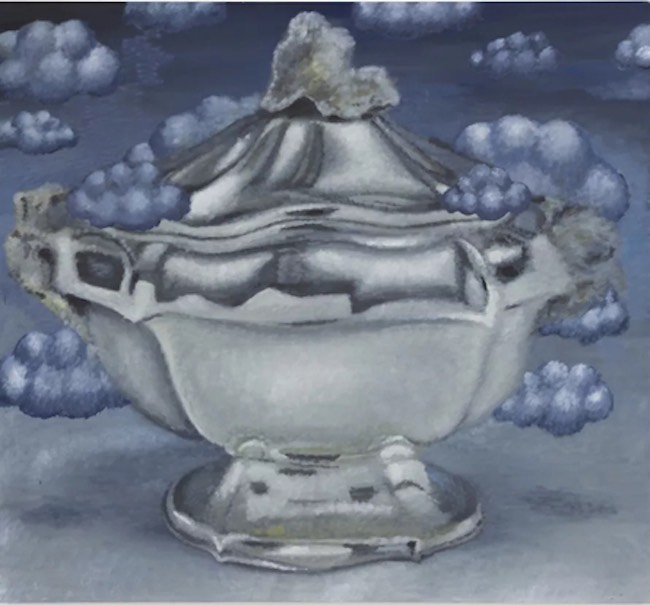

Le atmosfere sono gotiche, cupe, la gamma cromatica è terrosa, ombrosa, quasi la polvere del conformismo e della corsa a ottenere piuttosto che a essere coprisse la luce che splenderebbe se l’individuo fosse in grado di liberarsi da quel meccanismo di causa ed effetto dentro cui si trova imbrigliato. I soggetti dei suoi dipinti sono beni di consumo di lusso, dettagli di status symbol, di cose da possedere oppure antichità con un valore attribuito dalla legge di mercato più che da quello affettivo, e ancora spazzatura, bottiglie svuotate del loro contenuto tanto quanto la società contemporanea si svuota della sostanza per galleggiare nell’apparenza.

Eppure quelle atmosfere retrò, quegli oggetti vintage sembrano suggerire un declino, una decadenza rispetto ai fasti precedenti, come se Issy Wood sarcasticamente ponesse l’accento sull’attitudine di molti a continuare a vivere al di sopra delle proprie possibilità pur di restare legati a quella classe sociale che aveva permesso loro di avere un certo tenore di vita aggrappandosi a esso, come se potesse riempire un vuoto interiore che tuttavia non è mai stato colmato.

La tela Serve you right mostra un intero servizio di piatti in fine porcellana, di quelli appartenenti alle nonne e mantenuti perfettamente perché usati solo nelle occasioni speciali, e la loro predominanza sull’intero dipinto suggerisce quasi un’esposizione, una messa in vendita malgrado il legame affettivo. Issy Wood sembra sottolinearne il valore economico che quelle suppellettili possono avere per qualcuno appassionato di antichità, introducendo così il tema della commercializzazione di tutto ciò che appartiene alla vita attuale. Ogni oggetto è ridotto a una merce di scambio, a una transazione tra chi desidera disfarsi di qualcosa che ingombra gli spazi, o semplicemente ha bisogno di ricavare un profitto, e chi può permettersi di possedere qualsiasi sia il costo. Non c’è il senso del ricordo, l’emozionalità e il legame col passato in questo dipinto, la narrazione dell’autrice si riduce a una mera esposizione di merce in vendita.

Design for a feisty shoe è un’opera più surrealista, completamente eccentrica nella rappresentazione delle scarpe il cui tacco è costituito da statuine di piccoli leoni, a suggerire il bisogno di uscire dall’ordinarietà anche a costo di scadere nel cattivo gusto; la donna sfoggia le sue scarpe con orgoglio, come fossero un simbolo del suo potere d’acquisto, come fossero una sottolineatura della possibilità di concedersi tutto, anche ciò che non sarebbe necessario. Il modello della scarpa appartiene ancora una volta a un’epoca passata, dunque il messaggio dell’autrice è che il trash di oggi affonda le sue radici nei capricci dei ricchi del passato tramandando la tradizione che sconfina dal buon gusto per sistemarsi sull’eccesso a prescindere. Le linee sono sfumate, impalpabili quasi, evidenziando così la decontestualizzazione del dipinto e l’appartenenza a un mondo tra l’onirico e il reale.

Il dipinto Trick question car interior, realizzato a olio su velluto, mostra apertamente la critica di Issy Wood sul lusso e ciò che incarna nella società attuale, un vero e proprio divario tra una classe sempre più ricca e la maggior parte delle persone sempre più livellate verso il basso, e la sua velata critica si svela nel titolo in cui il termine domanda a trabocchetto precede la descrizione oggettiva di ciò che è visibile osservando il lavoro. Perché nel mondo surreale dell’autrice ogni cosa, ogni suo protagonista, ha un senso diverso da quello che appare, stimolando così l’osservatore a rimanere in bilico tra le sfumature visive che gli impediscono di avere una visione nitida dei tettagli, e il percorso mentale suggerito nei titoli.

Trash 2 rientra invece apertamente nel tema del consumismo, di quell’approccio usa e getta che appartiene alla contemporaneità e che induce le persone a dimenticare quanto invece in passato l’arte del riciclo era completamente diversa e forse persino più attenta di quanto non avvenga oggi. Le numerose bottiglie di plastica, le lattine, i contenitori vuoti dei detersivi, si accumulano e vanno ad ammassarsi prima di essere riutilizzati attraverso macchinari che hanno un costo elevato, mentre in passato le bottiglie erano di vetro, venivano semplicemente lavate e sterilizzate e poi riempite di nuovo. Meglio il passato o il presente?, sembra domandarsi Issy Wood. Non solo, quelle bottiglie vuote possono anche essere un’allegoria dell’uomo contemporaneo, troppo preoccupato di avere un involucro perfetto per avere il tempo di curare e coltivare l’interiorità, riducendosi a essere solo un esterno che una volta perduto lo smalto iniziale legato all’immagine della gioventù, appassisce e si svuota ripiegandosi su se stesso alla ricerca di un contenuto che non ha mai privilegiato.

Issy Wood ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre personali e collettive nel Regno Unito, negli Stati Uniti, Francia, Brasile, Cina, Germania, Italia, Belgio, Grecia, Paesi Bassi, Norvegia, Danimarca, Polonia, Scozia e le sue opere fanno parte delle collezioni permanenti di molti musei nel mondo.

ISSY WOOD-CONTATTI

Email: gallery@carlosishikawa.com

Sito web: www.carlosishikawa.com/artists/issywood/

Instagram: www.instagram.com/isywod/

Issy Wood’s Dark Surrealism, between discarded objects and hermetic criticism of consumer society

Some artists need to observe reality from a detached point of view, to make a shrewd analysis of those aspects of contemporary habits that they cannot ignore, which they must necessarily highlight in order to then express in their works all that criticism of existential flaws, of deficiencies that are superficially filled by distancing themselves from their inner selves. Among these artists, there are some who choose to express their point of view through shadows, showing a dusty, mysterious, and subtly disturbing figuration precisely because that is the feeling they receive from the environment in which they are immersed. Today’s protagonist has this kind of expressive approach, gloomy, slightly disturbing, mysterious, attracting the gaze by virtue of a familiar figuration, depicting known objects, but leaving beneath the surface considerations that are only revealed after lingering on the images and going beyond the first impression.

The birth of Surrealism in the early 20th century found a perfect synthesis between the need to investigate the unknown of the human psyche, to explore its anxieties, the ghosts of the mind that emerged only in dreams, and that tendency to reveal the dark side of the human soul, the hidden and unmentionable part that only a few artists of the past had had the courage to show in their artworks. In the 16th century, it was the Flemish artist Hieronymus Bosch who went against the expressive guidelines of the time, imagining universes in which all human instincts, where spontaneous rebellion against the rigid rules of morality and the church, came out in a surprising, disturbing, irrational way; his settings, devoid of perspective and full of characters and scenarios born of the author’s visions, showed how painting could be not only portraiture and real description but also a tool for recounting another reality, the parallel one that belonged to everyone’s inner self, while remaining secretly unconfessed. Based on Bosch‘s eccentric expressive vision, several centuries later, in the second half of the 19th century, developed the guidelines of some of the most extreme authors of Symbolism, such as Félicien Rops, who focused mainly on the most perverse sexual sphere, and Arnold Böcklin, who instead focused his production on the exploration of the afterlife and its silent manifestation in reality. The pictorial experiences of Symbolism, as well as those of Hieronymus Bosch, literally formed the foundations of Surrealism which, based on the theories of psychoanalysis developed by Sigmund Freud, sought to explore everything hidden beneath the façade presented by individuals, bringing to light all those ghosts relegated to a hidden corner of the mind that were released during sleep.

Salvador Dalí, in particular, was inspired by Bosch‘s scenarios, as well as by Félicien Rops‘ strong connection to the sexual sphere, but many other artists belonging to the new pictorial movement wanted to move towards mental reflections, the deceptive paradoxes in which the world unknowingly moves, and the need for the society of the time to break free from hypocrisy and focus on substance instead. This type of narrative approach characterized the work of René Magritte, who in some ways tried to approach the unexplained enigmas of Giorgio De Chirico‘s Metaphysical Art, while losing its geometricity and reference to Neoclassicism. Another author who stood out from the crowd during that period went beyond anything imaginable, representing nonsensical constructions where planes and spaces existed in an improbable perspective; the work of Mauritius Cornelius Escher amazed viewers with its ability to depict an infinitely possible world, showing humanity how everything that is logical and rational can be simply contradicted by breaking a predefined pattern, making everything achievable. The American artist Issy Wood, who has been living in London for many years, brings the experiences of the authors and movements mentioned above up to date with contemporary expressive poetics, carrying out a careful and unfiltered analysis of the ways of living and relating that prevail in an essentially consumerist present, where what an individual is seems to correspond to what they own or are able to buy.

The atmospheres are gothic and gloomy, the color palette earthy and shadowy, as if the dust of conformity and the race to obtain rather than to be were covering the light that would shine if the individual were able to free themselves from the mechanism of cause and effect in which they are trapped. The subjects of her paintings are luxury consumer goods, details of status symbols, things to possess, or antiques with a value attributed by market forces rather than sentimental value, and even trash, bottles emptied of their contents just as contemporary society empties itself of substance to float on appearances. Yet those retro atmospheres, those vintage objects seem to suggest a decline, a decadence compared to previous splendors, as if Issy Wood were sarcastically emphasizing the tendency of many to continue living beyond their means in order to remain tied to the social class that had allowed them to enjoy a certain standard of living, clinging to it as if it could fill an inner void that has never been filled. The canvas Serve you right shows an entire set of fine porcelain dishes, the kind that belonged to grandmothers and were kept in perfect condition because they were only used on special occasions, and their predominance in the entire painting almost suggests an exhibition, a sale despite the emotional attachment. Issy Wood seems to emphasize the economic value that these furnishings may have for someone passionate about antiques, thus introducing the theme of the commercialization of everything that belongs to current life.

Each object is reduced to a commodity, a transaction between those who want to get rid of something that clutters their space, or simply need to make a profit, and those who can afford to own it whatever the cost. There is no sense of memory, emotion, or connection to the past in this painting, the artist’s narrative is reduced to a mere display of merchandise for sale. Design for a feisty shoe is a more surrealist work, completely eccentric in its representation of shoes whose heels are made up of small lion figurines, suggesting the need to break out of the ordinary even at the cost of falling into bad taste. The woman proudly shows off her shoes, as if they were a symbol of her purchasing power, as if they were an emphasis on the possibility of indulging in everything, even what is not necessary. Once again, the shoe model belongs to a bygone era, so the author’s message is that today’s trash has its roots in the whims of the rich of the past, passing on a tradition that goes beyond good taste to settle on excess regardless. The lines are blurred, almost intangible, thus highlighting the decontextualization of the painting and its belonging to a world between the dreamlike and the real.

The painting Trick question car interior, done in oil on velvet, openly shows Issy Wood‘s criticism of luxury and what it embodies in today’s society a real gap between an increasingly wealthy class and the majority of people who are more and more levelled down, and her veiled criticism is revealed in the title, where the term ‘trick question’ precedes the objective description of what is visible when observing the work. Because in the author’s surreal world, everything, every character, has a different meaning from what it appears to be, thus stimulating the observer to remain poised between the visual nuances that prevent them from having a clear view of the details and the mental path suggested in the titles. Trash 2, on the other hand, openly addresses the theme of consumerism, that disposable approach that belongs to the contemporary world and that leads people to forget how different the art of recycling was in the past, and perhaps even more careful than it is today.

The numerous plastic bottles, cans, and empty detergent containers accumulate and pile up before being reused through expensive machinery, whereas in the past, bottles were made of glass, simply washed and sterilized, and then refilled. Which is better, the past or the present? Issy Wood seems to ask. Not only that, but those empty bottles can also be an allegory for contemporary man, too preoccupied with having a perfect exterior to have the time to nurture and cultivate his inner self, reducing himself to being only an exterior that, once it has lost the initial luster associated with the image of youth, withers and empties, folding in on itself in search of a content that it never prioritized. Issy Wood has participated in solo and group exhibitions in the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Brazil, China, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Greece, the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, Poland, and Scotland, and her works are part of the permanent collections of many museums around the world.