La tendenza a mettere in evidenza i lati nascosti e spesso enigmatici della realtà osservata era ed è caratteristica essenziale per quel gruppo di artisti che non vuole e non può limitarsi a imprimere nelle tele le proprie personali sensazioni su ciò che il suo sguardo vede; tuttavia esistono altri creativi che vanno a scavare più in fondo e filtrano quelle emozioni fino a farle giungere al pensiero, alla filosofia che oltre le immagini si manifesta. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi lascia emergere la singolare peculiarità di riuscire a fondere le sue riflessioni più profonde sulla realtà contemporanea con una sottile e morbida nostalgia nei confronti di un passato recente che appartiene al patrimonio culturale della generazione contemporanea.

Nel momento della sua nascita, poco dopo il primo decennio del Novecento, la Metafisica si contraddistinse, grazie alle opere del suo fondatore Giorgio De Chirico, per le atmosfere enigmatiche e misteriose che avvolgevano l’osservatore pur fuoriuscendo da una realtà rappresentata apparentemente familiare, conosciuta; tuttavia il senso di desolazione e la decontestualizzazione degli elementi inseriti nelle tele infondevano disorientamento e sottintendevano significati nascosti e da interpretare. Il non senso della completa assenza di figure umane sostituite da manichini, personaggi mitologici, e il tempo sospeso delle immense opere di De Chirico, così come la desolazione della quotidianità, il mistero di figure immaginarie a metà tra sogno e incubo di Carlo Carrà e ancora il palpitare vibrante delle nature morte capaci di irradiare la loro misteriosa energia all’intera tela e anche oltre di Giorgio Morandi, hanno tracciato una linea di demarcazione piuttosto netta con l’altro movimento che si proponeva di esplorare la psiche umana, le sue inquietudini e i suoi incubi, cioè il Surrealismo. In entrambe le correnti si volle mantenere il contatto con la figurazione proprio per dare all’osservatore l’illusione di essere in grado di decriptare la realtà narrata salvo poi condurlo all’interno di un mondo irreale in cui perdere i riferimenti e lasciarsi trasportare verso il pensiero filosofico, l’approccio esplorativo dell’artista. Dunque il contatto con il Realismo del secolo precedente fu soltanto formale, una forma narrativa che però assunse significati completamente differenti, rinnegando in qualche modo quella mera aderenza a ciò che lo sguardo coglieva e dando rilievo a tutto ciò che non poteva essere visto ma non per questo restare inesplorato; le certezze acquisite che andavano scomparendo a causa dei tempi di guerra e gli studi sulla psiche umana dello psicanalista austriaco Sigmund Freud furono lo stimolo e la base di partenza per la ricerca Surrealista ma anche per quella Metafisica perché in fondo, pur esprimendosi in maniera più estrema il primo e più meditata e riflessiva il secondo, entrambi cercavano di indagare il non visibile, le energie sottili e misteriose che avvolgono la realtà e che giungono inevitabilmente all’essere umano. Nella realtà contemporanea i confini tra i vari movimenti sono divenuti più sfumati, l’intento creativo ha trovato una mediazione anche, e soprattutto, perché le battaglie ideologiche hanno già avuto il loro compimento e così gli artisti attuali hanno la libertà di poter dar vita a un linguaggio personale che si pone spesso al centro, in una posizione più morbida rispetto al passato, più mediata dall’interpretazione soggettiva. La romana Silvia Landini mostra uno stile delicato, leggero, quasi vellutato, attraverso il quale mette in evidenza luoghi, simboli, personaggi che hanno colpito la sua attenzione con la stessa intensità con la quale sono entrati nell’immaginario comune oppure con la delicata bellezza che spesso si nasconde a un occhio distratto ed emerge invece in modo chiaro in virtù del filtro emotivo dell’artista.

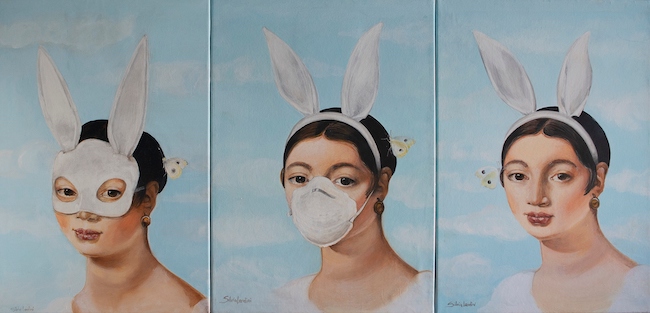

La Metafisica della Landini perde quel senso di mistero che lo stile ebbe inizialmente per spostare il fulcro della sua narrazione sull’espressività, sulla morbidezza delle sensazioni che avvolgono oggetti, scorci di paesaggi e miti moderni, permettendo alla loro voce silenziosa di fuoriuscire, mettendone in evidenza quei dettagli, quegli aspetti che si svelano solo grazie alla lente di ingrandimento sotto la quale l’artista li pone.

Il tocco di Silvia Landini è poetico ma al tempo stesso realista, nella descrizione delle scene e dei soggetti che rende protagonisti, forse il suo sguardo è più introspettivo che romantico, più orientato alla comprensione del significante che non all’emozione che emerge in lei, quasi come se volesse invitare il fruitore ad andare oltre il visibile, ma anche oltre il personale sentire per porsi in posizione di ascolto della realtà osservata.

L’opera Land è un perfetto esempio della capacità della Landini di liberare le vibrazioni di un oggetto e di indurre alla riflessione sul senso del trovarsi lì dell’auto, in quel luogo esatto, del suo essere un mezzo ma anche un protagonista indiscusso di avventure e di esplorazioni, metafora della tendenza dell’uomo a circondarsi di zavorre pur sapendo di dover intraprendere un viaggio. Oppure, al contrario, ciò che l’artista intende narrare è l’importanza dello spostamento, dell’andare da un posto all’altro, indipendentemente dalla destinazione, ciò che importa è il bagaglio di esperienze che viene raccolto e portato con sé, di luogo in luogo, di accadimento in accadimento.

Così come in Vespa, l’icona degli anni Sessanta rappresenta non più un mezzo di locomozione bensì un ricordo dolce di serate d’estate con il vento tra i capelli, di gite fuori porta con gli amici, trasformandosi così in un simbolo di un’intera epoca, di una fase in cui tutto sembrava possibile, in cui le giornate erano spensierate e il mondo sembrava essere un luogo più accogliente, più piacevole, rispetto all’evoluzione che nel corso del tempo ha subìto; i fiori che incorniciano l’iconica due ruote accrescono la delicatezza emozionale, e al tempo stesso accompagnano il corso della memoria della Landini, così come dell’osservatore, che pone il soggetto al centro dell’opera in qualche modo sospeso, incastrato all’interno di un tempo non tempo che gli regala l’immortalità.

La sua impronta fortemente Metafisica emerge in particolar modo nei paesaggi, o meglio negli scorci come la tela Foro, che descrivono un mondo immaginato, quasi ideale, in cui il silenzio accompagna le immagini riprodotte e contribuisce a focalizzare lo sguardo sull’immobilità che spesso accompagna alcuni elementi che spesso si tende a non vedere più, a considerare invisibili perché parte di un vissuto o di un quotidiano all’interno del quale il dettaglio viene perso, distrattamente ignorato per dare la priorità a quell’urgenza del vivere che sembra essere divenuta l’imperativo della contemporaneità. Ecco, attraverso lo sguardo dell’artista il tempo si ferma per mettere in risalto quel particolare dimenticato, quella parte di universo che passa davanti agli occhi ogni giorno senza che l’individuo sia in grado di osservarlo, di interrogarsi su cosa la sua presenza rappresenti, su quanto le sue pareti abbiano visto scorrere e quanto ancora vedranno perché in fondo è proprio a esse che l’uomo ha donato quell’immortalità a cui da sempre egli stesso anela senza riuscire a ottenerla.

Poi invece, quando racconta di personaggi che appartengono alla cultura comune, quei nuovi miti in grado di strappare un sorriso attraverso il solo ricordo, l’approccio di Silvia Landini si avvicina di più al Realismo, pur senza perdere la sua inclinazione simbolica, per descrivere quella dolcezza ingenua, quell’autoironia, quell’imperdonabile scanzonatezza che contraddistingue Alberto Sordi, protagonista della tela Selfie, ma anche Charlie Chaplin, a cui l’artista dedica un’intera parete immortalandolo nella sua immagine più classica e conosciuta, quella tratta dal film Il monello.

Silvia Landini ha un passato di art director in un’agenzia pubblicitaria dunque ha una visione aperta alla sperimentazione artistica, infatti riproduce e adatta le sue opere in soluzioni di uso quotidiano, dai vassoi alle porte e ai murales; ha partecipato a numerose mostre collettive a Roma tra cui quelle al Macro, al Museo di Arte Moderna di Roma e in qualità di artista ospite a qualche edizione della mostra dei Cento Pittori di via Margutta.

SILVIA LANDINI-CONTATTI

Email: silvia_landini@virgilio.it

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/landinidecorazioni/

Silvia Landini’s soft touch, between Realism and Metaphysics to keep memories and objectivity united

The tendency to highlight the hidden and often enigmatic sides of the reality observed was and is an essential characteristic of that group of artists who do not want and cannot limit themselves to imprinting on their canvases their own personal sensations on what they see; however, there are other creatives who dig deeper and filter those emotions until they reach the thought, the philosophy that manifests itself beyond the images. The artist I am going to tell you about today reveals the singular peculiarity of being able to blend her deepest reflections on contemporary reality with a subtle and soft nostalgia for a recent past that belongs to the cultural heritage of the contemporary generation.

At the time of its birth, shortly after the first decade of the twentieth century, Metaphysical Art stood out, thanks to the artworks of its founder Giorgio De Chirico, for the enigmatic and mysterious atmospheres that enveloped the observer even though they were outside of an apparently familiar represented reality; however, the sense of desolation and the decontextualisation of the elements included in the canvases instilled disorientation and implied hidden meanings that needed to be interpreted. The non-sense of the complete absence of human figures replaced by mannequins, mythological characters, and the suspended time of De Chirico’s immense artworks, as well as the desolation of everyday life, the mystery of imaginary figures halfway between dream and nightmare by Carlo Carrà, and the vibrant palpitation of still lifes capable of radiating their mysterious energy to the entire canvas and beyond by Giorgio Morandi, drew a rather clear line of demarcation with the other movement that set out to explore the human psyche, its restlessness and nightmares, namely Surrealism.

In both currents, the aim was to maintain contact with figuration in order to give the observer the illusion of being able to decipher the narrated reality, only to be led into an unreal world in which the he would lose his bearings and be transported towards philosophical thought, the artist’s exploratory approach. So the contact with the Realism of the previous century was only formal, a narrative form which, however, took on completely different meanings, in some way repudiating that mere adherence to what the eye could see and emphasising everything that could not be seen but which did not remain unexplored; the acquired certainties that were disappearing due to wartime and the studies on the human psyche by the Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud were the stimulus and the starting point for Surrealist research, but also for Metaphysical research because after all, although the former expressed itself in a more extreme manner and the latter more meditated and reflective, both sought to investigate the non-visible, the subtle and mysterious energies that envelop reality and inevitably reach the human being. In the contemporary world, the boundaries between the various movements have become more blurred, the creative intent has found a mediation also, and above all, because the ideological battles have already had their completion and so today’s artists have the freedom to be able to give life to a personal language that is often at the centre, in a softer position than in the past, more mediated by subjective interpretation.

Roman artist Silvia Landini displays a delicate, light, almost velvety style, through which she highlights places, symbols and characters that have caught her attention with the same intensity with which they have entered the common imagination, or with the delicate beauty that is often hidden from a distracted eye and emerges instead clearly by virtue of the artist’s emotional filter. Landini’s Metaphysics loses that sense of mystery that the style initially had in order to shift the fulcrum of its narration to expressiveness, to the softness of the sensations that envelop objects, glimpses of landscapes and modern myths, allowing their silent voice to emerge, highlighting those details, those aspects that are only revealed through the magnifying glass under which the artist places them. Silvia Landini’s touch is poetic but at the same time realistic, in the description of the scenes and subjects that she makes protagonists. Perhaps her gaze is more introspective than romantic, more oriented towards understanding the signifier than the emotion that emerges in her, almost as if she wanted to invite the viewer to go beyond the visible, but also beyond personal feeling to place himself in a position of listening to the reality observed. The artwork Land is a perfect example of Landini’s ability to release the vibrations of an object and to prompt reflection on the meaning of the car’s being there, in that exact place, of its being a means of transport but also an undisputed protagonist of adventures and explorations, a metaphor for man’s tendency to surround himself with ballast even though he knows he must undertake a journey. Or, on the contrary, what the artist intends to narrate is the importance of movement, of going from one place to another, regardless of the destination, what matters is the baggage of experience that is collected and carried with one’s body, from place to place, from event to event.

So as of Vespa, the icon of the Sixties is no longer a means of locomotion but a sweet memory of summer evenings with the wind in the hair, of trips out of town with friends, thus becoming a symbol of an entire era, of a phase in which everything seemed possible, in which days were carefree and the world seemed to be a more welcoming, more pleasant place, compared to the evolution that it has undergone over time; the flowers that frame the iconic two-wheeler increase the emotional delicacy, and at the same time accompany the course of Landini’s memory, as well as that of the observer, who places the subject at the centre of the painting in some way suspended, embedded within a timelessness that gives it immortality. Her strongly metaphysical imprint emerges particularly in the landscapes, or rather in the glimpses such as the canvas Foro, which describe an imagined, almost ideal world, in which silence accompanies the images reproduced and helps to focus the gaze on the immobility that often accompanies certain elements that we tend not to see any more, to consider invisible because they are part of an experience or a daily routine within which the detail is lost, distractedly ignored in order to give priority to that urgency of living that seems to have become the imperative of contemporaneity.

Here, through the artist’s gaze, time stops to highlight that forgotten detail, that part of the universe that passes before the eyes every day without the individual being able to observe it, to question himself on what its presence represents, on how much his walls have seen flowing and how much more they will see because, after all, it is to them that man has given that immortality for which he himself has always yearned without succeeding in obtaining it. But then, when she tells of characters belonging to common culture, those new myths capable of bringing a smile to one’s face through mere recollection, Silvia Landini’s approach comes closer to Realism, without losing its symbolic inclination, to describe that naive sweetness, that self-irony, that unforgivable easy-goingness that distinguishes Alberto Sordi, the protagonist of the canvas Selfie, but also Charlie Chaplin, to whom the artist dedicates an entire wall, immortalising him in his most classic and well-known image, from the film The Kid. Silvia Landini has a background as an art director in an advertising agency and therefore has an open mind to artistic experimentation, in fact she reproduces and adapts her artworks in everyday solutions, from trays to doors and murals; she has taken part in numerous collective exhibitions in Rome including those at the Macro, the Museum of Modern Art of Rome and as a guest artist in some editions of the Cento Pittori di via Margutta exhibition.