Andare a fondo di tutto ciò che si verifica nella quotidianità implica uno sforzo di ascolto e di indagine su tutte le sensazioni generate dagli eventi, dal rapporto di causa ed effetto che si sviluppa nella mente dell’individuo durante l’incontro tra oggettività e reazione soggettiva, tra capacità di prendere atto e di accettare gli accadimenti oppure restare legati a un prima non più esistente a causa del quale possono nascere frustrazioni e sofferenze. L’animo sensibile degli artisti spesso va a indagare esattamente quel punto interiore in cui tutte queste emozioni si liberano e affiorano in maniera inconscia avvolgendo la sostanza più autentica e diffondendosi poi verso l’esterno. Il protagonista di oggi, attraverso uno stile pittorico in cui mescola tecnica tradizionale a un’innovazione più sperimentale, affonda la sua analisi verso quei percorsi inconsapevoli ma spontanei che vanno a concretizzarsi sulla tela in ambientazioni irreali e simboliche.

Nel corso dei primi decenni del Ventesimo secolo l’arte mostrò un interesse sempre crescente verso l’individuo, l’uomo con tutte le sue fragilità, le insicurezze, l’essenza che non poteva essere sostituita da alcuna macchina, contrariamente a quanto avvenne dopo la Rivoluzione Industriale che aveva ridotto le persone a semplici parti di una catena di montaggio, e non poteva neanche essere soffocata dalle sofferenze degli eventi esterni. Già con i Fauves e l’Espressionismo si verificò un’opposizione alla tradizione accademica che metteva al primo posto l’armonia estetica e la perfezione esecutiva private della soggettività dell’autore di un’opera, ma il vero stravolgimento avvenne con la fine della prima guerra mondiale, quando un gruppo di artisti capitanati da Salvador Dalì decise di creare uno stile in cui i fantasmi della mente fuoriuscissero tanto quanto la nuova psicanalisi di Freud fu in grado di fare proprio analizzando i comportamenti dei reduci di guerra.

Il Surrealismo rifiutò ogni canone estetico e, pur mantenendo uno stile pittorico perfetto dal punto di vista formale, nell’aspetto figurativo la narrazione andava a rappresentare tutti quei fantasmi, gli incubi, i disagi che emergevano quando la mente razionale si abbandonava alla fase del sonno. Eppure anche all’interno del movimento non vi furono solo i mostri e gli eccessi di Salvador Dalì e di Max Ernst bensì si sviluppò anche un approccio più sottile, più meditativo e volto a indagare i misteri e il senso della vita, che contraddistinse la produzione artistica di René Magritte. Le linee pulite e pittoricamente perfette incontravano pertanto un’interiorità disturbata o semplicemente destabilizzata dall’incontro, o forse sarebbe meglio dire scontro, tra realtà e percezione dell’essere umano, spesso discostanti proprio a causa del lavoro di trasformazione compiuto dall’interiorità.

Non solo, caratteristica di tutti gli esponenti del Surrealismo fu quella di introdurre e nascondere simboli all’interno di ogni tela, dettagli non rilevabili al primo sguardo bensì necessitanti un soffermarsi più prolungato, un’esplorazione approfondita in virtù della quale l’osservatore potesse immergersi in quelle atmosfere inquietanti, enigmatiche e ipnotiche in cui il visibile incontrava l’immaginario. L’attenzione a considerare i disagi profondi dell’uomo nella società post-bellica fu centrale anche per tutta l’Arte Brut, movimento fondato dopo la seconda guerra mondiale da Jean Dubuffet che spingeva i pazienti degli istituti per malattie mentali a dipingere come terapia per liberare la psiche o per trovare sfogo ai propri disagi attraverso il gesto creativo. Pur essendo profondamente diversi dal punto di vista formale, l’Espressionismo, il Surrealismo e l’Arte Brut misero l’essere umano al centro della ricerca pittorica, a discapito dell’armonia estetica, tralasciando ogni regola accademica ma ritrovando una connessione profonda tra tutto ciò che appartiene all’interiorità e la visione che da quel sentire emerge e che si trasforma poi in colori ed espressività pittorica.

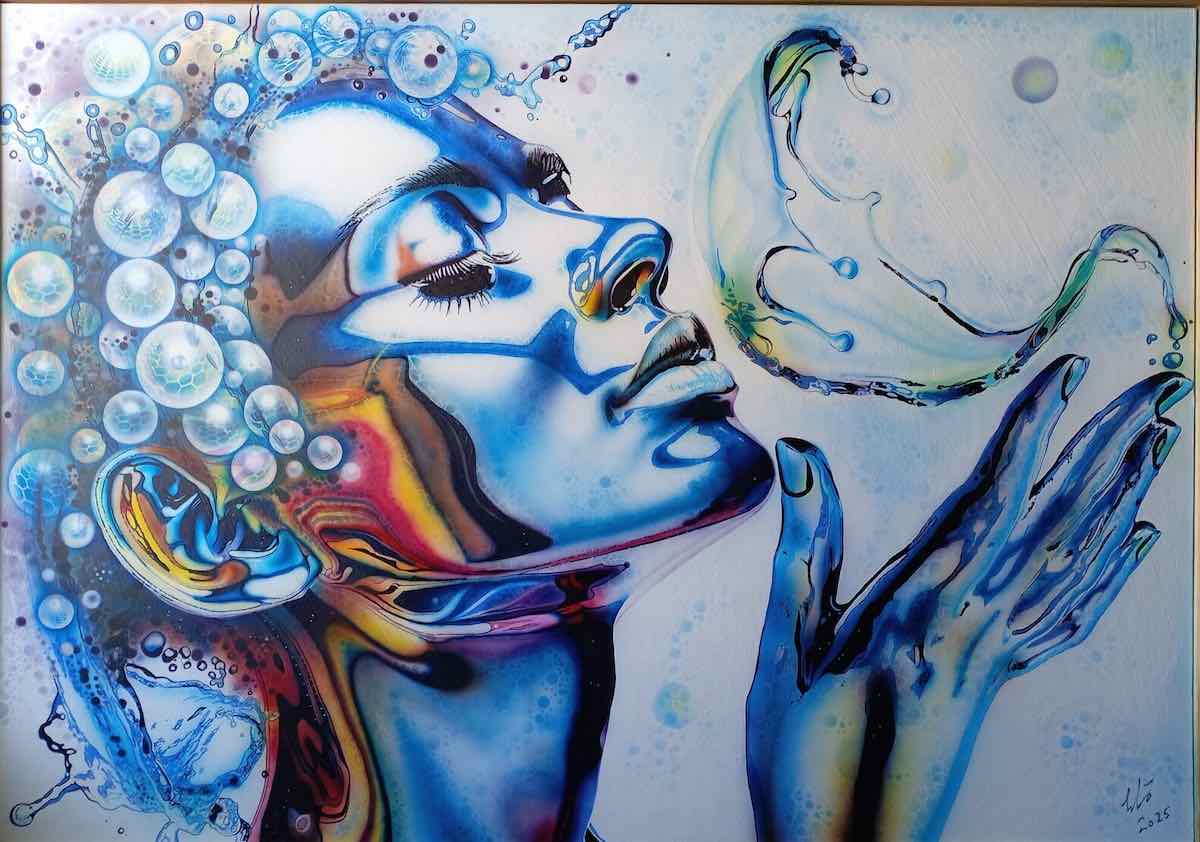

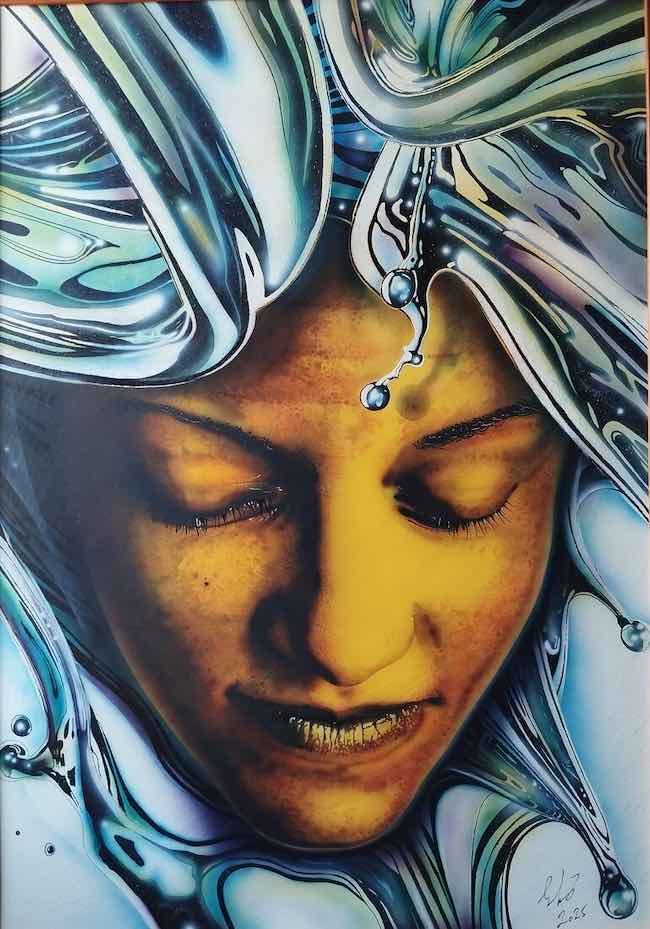

L’artista serbo György Sütő percorre il medesimo sentiero del Surrealismo ammorbidendo le atmosfere e senza ricorrere agli eccessi narrativi di Dalì e di Ernst, tendendo piuttosto verso l’approfondimento esistenziale di Magritte e dunque aggiungendo alle sue tele un aspetto Metafisico avvolgente in cui spesso la fluidità diviene cornice per focalizzarsi sulle espressioni che nascondono un intero mondo interiore; d’altro canto la sua tecnica, impeccabile nella figurazione tendente all’Iperrealismo, viene in altre tele resa impalpabile ed evanescente in alcuni punti dall’utilizzo della tecnica dell’Aerografia, in virtù della quale il colore viene letteralmente nebulizzato infondendo alla composizione finale un aspetto morbido.

Non solo, lo studio della psiche umana con cui è costantemente a contatto nel suo impiego principale, di fatto una vera e propria missione, come assistente presso strutture per anziani, lo mette davanti alla soggettivizzazione della realtà, a un’interpretazione individuale sugli accadimenti e gli eventi della vita attraverso cui comprende l’assoluta relatività di tutto ciò che appartiene alla vita.

Le sue opere sono dunque un punto di contatto quasi soprannaturale tra l’esigenza di andare a fondo, ascoltare, riflettere e fare proprie le sensazioni espresse in maniera quasi irrazionale nella fase più adulta della mente, quella in cui si compie quasi una regressione verso l’infanzia che toglie filtri e veli della formalità, e il suo ricevere quella girandola di sentimenti letteralmente possedendoli per poi essere in grado di rielaborarli e di emanarli attraverso il catartico gesto pittorico.

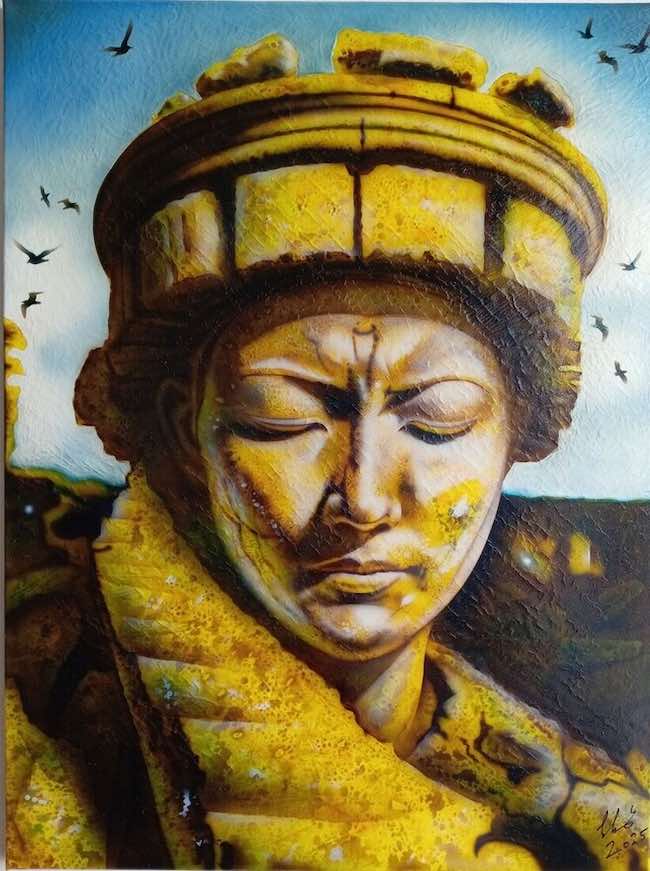

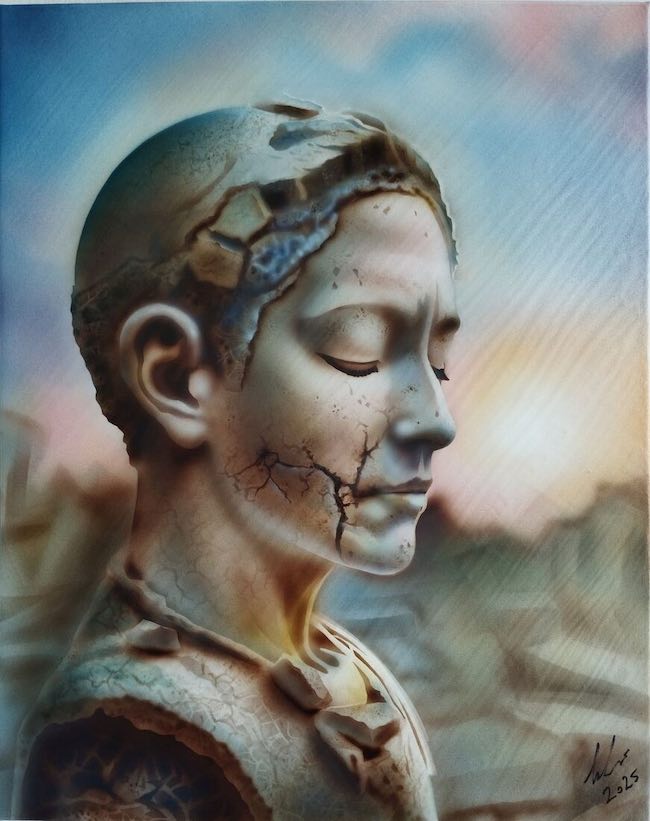

Nell’opera Demencia, György Sütő mostra tutta la sua capacità empatica, la sensibilità in virtù della quale riesce a cogliere il disagio di una mente non più capace di rimanere legata ai propri ricordi, alla realtà che ha costituito il suo cammino; la guancia della donna raffigurata come un’entità extra terrestre, appartenente a un mondo lontano e sconosciuto, appare segnata da uno squarcio, come a voler sottolineare la spaccatura non più sanabile con cui tutte le persone affette da quella degenerazione mentale sono costrette a convivere. Lo sfondo, realizzato con la tecnica dell’Aerografo, è fortemente sfumato perché la nitidezza della memoria non appartiene più al tempo presente, bensì resta un’atmosfera indefinita in cui la logica vaga confusa alla ricerca di appigli che possano ricondurla alla lucidità. Il simbolismo della figura appartenente a un mondo parallelo si lega esattamente alla lontananza in cui queste persone galleggiano come non appartenessero più all’universo reale.

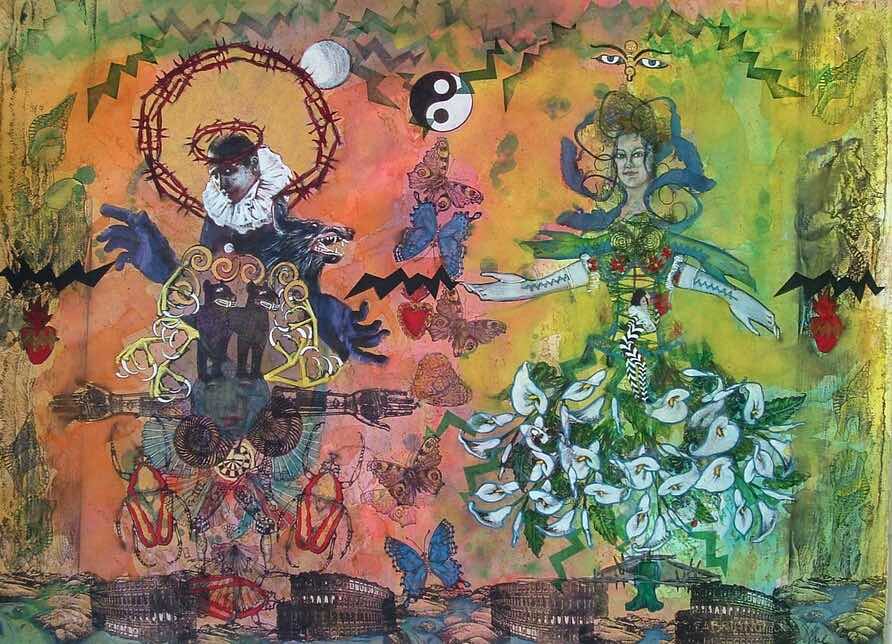

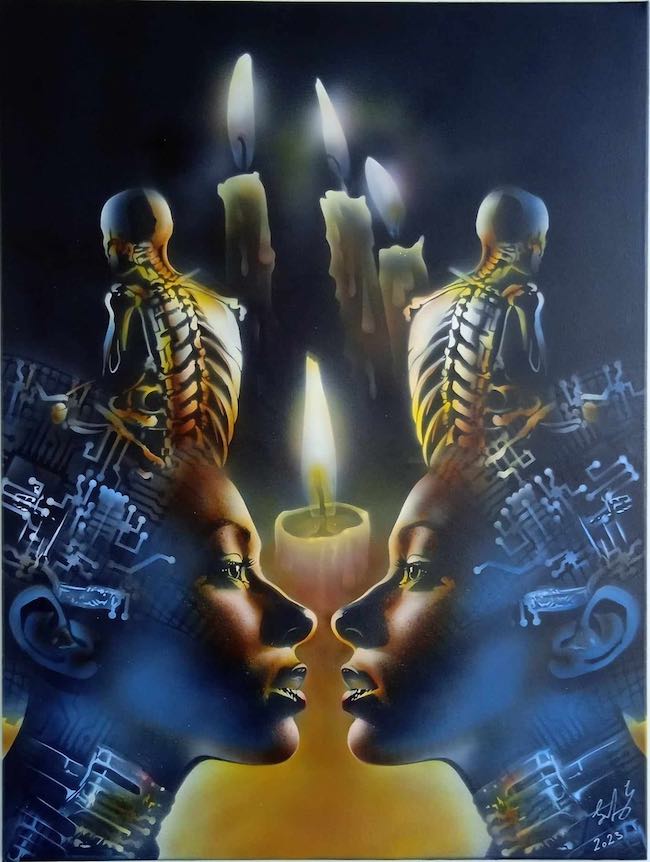

Eternal Hope descrive invece il desiderio tipicamente umano di cercare un modo per essere immortale, per non permettere al corpo di estinguersi anche a costo di denaturarsi e di affidare a una macchina, a un microchip, la possibilità di vivere per sempre; questo tipo di pensiero è prevalentemente materialista, ecco dunque il riferimento e forse la velata critica alla società contemporanea, poiché dal punto di vista spiritualista il corpo è solo un abito in cui l’anima, quella sì immortale, decide di incarnarsi di vita in vita. I profili delle due donne sono quindi uno davanti all’altro, i loro sguardi sono vuoti perché la tecnologia che hanno scelto di farsi impiantare per rendersi eterne, le ha di fatto condotte verso una perdita della loro umanità; questo concetto è espressio da György Sütő con la presenza di scheletri che spiccano sullo sfondo in alto e da una candela che rappresenta il soffio di vita che si è completamente distaccato dal loro corpo. Anche il tema dell’amore viene spesso affrontato dall’autore ed esplorato in tutte le sue sfaccettature, e in questo caso la psiche cede il passo alla natura totalemente emotiva del sentimento più alto, quello in grado di unire e di oltrepassare ogni confine.

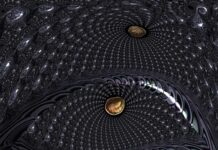

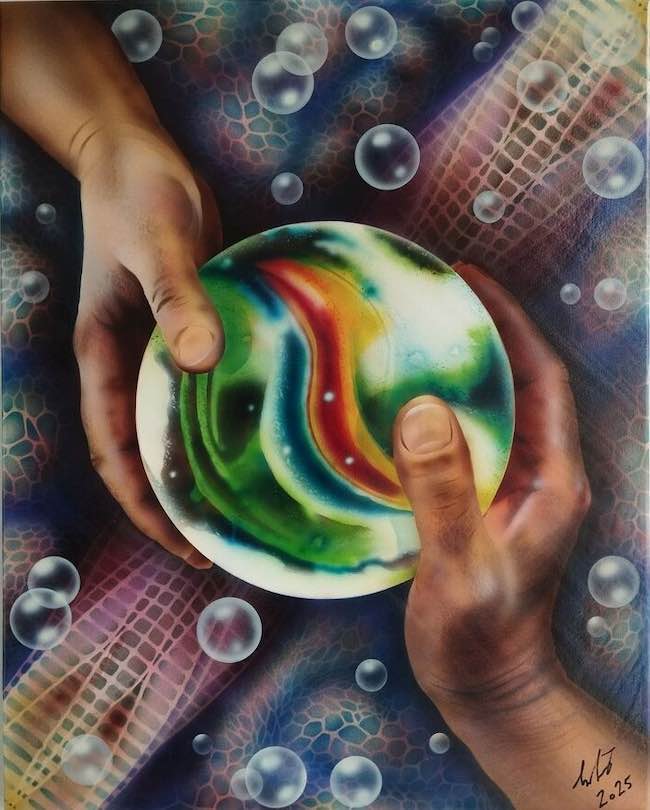

In The Cosmogony of Encounter l’attenzione si focalizza sulla sfera centrale che ricorda il Tao cinese, simbolo di completamento, di perfezione, di compiutezza, sensazioni che si avvertono nel momento in cui ci si trova di fronte alla persona perfetta, quella con cui bilanciare le rispettive mancanze e in virtù di quel nuovo equilibrio riuscire a evolvere. L’incontro non è mai casuale, sembra suggerire György Sütő, è sempre frutto di un’inconscia ricerca che non spinge verso chi si crede possa andar bene, bensì verso chi va bene quasi senza crederlo o averlo pensato. Le due mani, protagoniste della tela insieme alla sfera centrale, sostengono quell’entità simbolica appartenente a una dimensione non terrena, e sembrano non poter più staccarsi perché rinunciare a quel contatto equivarrebbe a rifiutare tutto ciò che ormai sembra contare al punto di essere essenziale. La magia dell’attimo dell’incontro viene raccontata attraverso sfumature leggere e un’ambientazione cosmica, quasi ancestrale, mentre le piccole sfere trasparenti che aleggiano sul resto della tela simboleggiano tutte le precedenti esperienze di vita, tutte le persone che hanno attraversato e incrociato il cammino dei due, modificando la loro singola evoluzione fino a condurli l’uno verso l’altro.

György Sütő attualmente vive e lavora in Ungheria, partecipa regolarmente a mostre collettive internazionali in Ungheria, in Francia, negli Stati Uniti, in Spagna, in Australia, in Austria, in Lussemburgo, in Italia, è stato membro del Circolo delle Belle Arti della città di Tapolca, fino al 2017, anno di scioglimento dell’associazione, e dal 2022 è membro del Laboratorio di Belle Arti Cristiane t’ARS.

GYÖRGY SÜTŐ-CONTATTI

Email: gyurikapostaja@gmail.com

Sito web: www.gysutoart.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100003130679148

Instagram: www.instagram.com/gysutoart/

Deep introspection on the essence and psyche in György Sütő’s Metaphysical Surrealism

Getting to the bottom of everything that happens in everyday life requires an effort to listen to and investigate all the sensations generated by events, by the cause-and-effect relationship that develops in the mind of the individual during the encounter between objectivity and subjective reaction, between the ability to take note of and accept events or remain tied to a past that no longer exists, which can give rise to frustration and suffering. The sensitive soul of artists often investigates precisely that inner point where all these emotions are released and surface unconsciously, enveloping the most authentic substance and then spreading outwards. Today’s protagonist, through a pictorial style that blends traditional technique with more experimental innovation, sinks his analysis into those unconscious but spontaneous paths that take shape on the canvas in unreal and symbolic settings.

During the early decades of the 20th century, art showed an ever-growing interest in the individual, in human beings with all their frailties and insecurities, in the essence that could not be replaced by any machine, contrary to what happened after the Industrial Revolution which had reduced people to mere parts of an assembly line, and could not even be stifled by the suffering caused by external events. Already with the Fauves and Expressionism, there was opposition to the academic tradition that prioritized aesthetic harmony and technical perfection, depriving of subjectivity the author of an artwork; but the real upheaval came with the end of the First World War, when a group of artists led by Salvador Dalí decided to create a style in which the ghosts of the mind emerged as much as Freud’s new psychoanalysis was able to do by analyzing the behavior of war veterans. Surrealism rejected all aesthetic canons and, while maintaining a formally perfect pictorial style, in its figurative aspect the narrative represented all those ghosts, nightmares, and discomforts that emerged when the rational mind abandoned itself to the phase of sleep. Yet even within the movement there were not only the monsters and excesses of Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst, but also a more subtle, meditative approach aimed at investigating the mysteries and meaning of life, which characterized the artistic production of René Magritte. Clean, pictorially perfect lines thus merged to an inner world that was disturbed or simply destabilized by the encounter, or perhaps it would be better to say the clash, between reality and human perception, often divergent precisely because of the work of transformation carried out by the inner world. Not only that, a characteristic of all exponents of Surrealism was to introduce and hide symbols within each canvas, details that were not detectable at first glance but required a longer pause, an in-depth exploration by virtue of which the observer could immerse in those disturbing, enigmatic, and hypnotic atmospheres in which the visible met the imaginary.

The focus on considering the profound discomforts of man in post-war society was also central to the entire Art Brut movement, founded after World War II by Jean Dubuffet, who encouraged patients in mental institutions to paint as a form of therapy to free their psyche or to find an outburst for their discomfort through creative expression. Although profoundly different from a formal point of view, Expressionism, Surrealism, and Art Brut placed the human being at the center of pictorial research, to the detriment of aesthetic harmony, leaving aside all academic rules but rediscovering a profound connection between everything that belongs to the inner self and the vision that emerges from that feeling and is then transformed into colors and pictorial expressiveness. Serbian artist György Sütő follows the same path as Surrealism, softening the atmospheres and without resorting to the narrative excesses of Dalí and Ernst, tending instead towards the existential depth of Magritte and thus adding to his canvases an enveloping Metaphysical aspect in which fluidity often becomes a frame for focusing on expressions that conceal an entire inner world; on the other hand, his technique, impeccable in its figuration tending to Hyperrealism, is rendered intangible and evanescent in some parts of other canvases through the use of Airbrushing, whereby color is literally sprayed on, giving the final composition a soft appearance. Not only that, the study of the human psyche, with which he is constantly in contact in his main job—in fact, a real mission—as an assistant in facilities for the elderly, confronts him with the subjectivization of reality, with an individual interpretation of life’s happenings and events through which he understands the absolute relativity of everything that belongs to life.

His artworks are therefore an almost supernatural point of contact between the need to go deeper, listen, reflect, and internalize the feelings expressed in an almost irrational way in the more adult phase of the mind, the one in which there is almost a regression to childhood that removes the filters and veils of formality, and his receiving that whirlwind of sensations, literally possessing them in order to then be able to rework and emanate them through the cathartic gesture of painting. In the painting Demencia, György Sütő shows all his empathic ability, the sensitivity by virtue of which he manages to grasp the discomfort of a mind no longer able to remain tied to its memories, to the reality that has constituted its path; the cheek of the woman depicted as an extraterrestrial entity, belonging to a distant and unknown world, appears marked by a gash, as if to emphasize the irreparable rift with which all people affected by that mental degeneration are forced to live.

The background, created using the Airbrush technique, is heavily blurred because the clarity of memory no longer belongs to the present time, but remains an undefined atmosphere in which logic wanders confusedly in search of footholds that can lead it back to lucidity. The symbolism of the figure belonging to a parallel world is linked precisely to the distance in which these people float as if they no longer belonged to the real universe. Eternal Hope, on the other hand, describes the typically human desire to seek a way to be immortal, to prevent the body from dying even at the cost of denaturing itself and entrusting a machine, a microchip, with the possibility of living forever; this type of thinking is predominantly materialistic, hence the reference and perhaps the veiled criticism of contemporary society, since from a spiritualist point of view, the body is only a garment in which the soul, which is immortal, decides to incarnate itself from life to life. The profiles of the two women are therefore facing each other, their gazes empty because the technology they have chosen to implant in themselves to be eternal has in fact led them to a loss of their humanity; this concept is expressed by György Sütő with the presence of skeletons standing out in the background at the top and a candle representing the breath of life that has completely detached itself from their bodies. Also the theme of love is also often addressed by the author and explored in all its facets, and in this case the psyche gives way to the totally emotional nature of the highest feeling, the one capable of uniting and transcending all boundaries. In The Cosmogony of Encounter, the focus is on the central sphere reminiscent of the Chinese Tao, a symbol of completion, perfection, and fulfillment, feelings that are experienced when one encounters the perfect person, the one with whom the respective shortcomings can be balanced and, by virtue of that new balance, one can evolve.

The encounter is never random, György Sütő seems to suggest, it is always the result of an unconscious search that does not push us towards those we think will be right for us, but rather towards those who are right for us almost without believing or thinking so. The two hands, protagonists of the canvas together with the central sphere, support that symbolic entity belonging to a non-earthly dimension, and seem unable to detach themselves because giving up that contact would be tantamount to rejecting everything that now seems to matter to the point of being essential. The magic of the moment of encounter is conveyed through subtle nuances and a cosmic, almost ancestral setting, while the small transparent spheres floating above the rest of the canvas symbolize all previous life experiences, all the people who have crossed paths with the two changing their individual evolution until leading them to each other. György Sütő currently lives and works in Hungary and regularly participates in international group exhibitions in Hungary, France, the United States, Spain, Australia, Austria, Luxembourg, and Italy. He was a member of the Tapolca Fine Arts Circle until 2017, when the association was dissolved, and since 2022 he has been a member of the t’ARS Christian Fine Arts Laboratory.