L’interrogazione sul senso della vita, sulle pulsioni più profonde e sulla necessità di cercare punti di riferimento solidi appartengono a quel ventaglio sfaccettato di emozioni con cui si confronta quotidianamente l’uomo contemporaneo; l’arte di conseguenza non può non rappresentare le difficoltà e le inquietudini interiori che contraddistinguono il Ventunesimo secolo quanto, per altre circostanze oggettive, avevano caratterizzato il Ventesimo. All’interno di questa ricerca introspettiva alcuni artisti restano all’interno del proprio mondo interiore avvertendo la necessità di liberare quelle energie altrimenti inespresse, altri invece cercano di porsi in atteggiamento di ascolto e di osservazione della realtà circostante provando a dare un’interpretazione attraverso la propria produzione. Il protagonista di oggi sceglie questa seconda via per trasmettere al fruitore il suo punto di vista su tutto ciò che lo circonda e su cui il suo sguardo si sofferma proprio perché spesso ignorato dai più nel significato più nascosto.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte la scultura ha assunto ruoli celebrativi, rappresentativi di una realtà che doveva apparire maestosa e regale, almeno fino a quando le avanguardie hanno scomposto ogni canone esecutivo per entrare in un campo differente, quello delle sensazioni, del non visto, del mistero dell’esistenza che non riusciva a essere svelato malgrado gli sforzi dell’essere umano. Già nel secolo precedente Auguste Rodin, considerato il padre della scultura moderna, aveva posto al centro della sua ricerca artistica il carattere e il pensiero emotivo dei personaggi da lui raffigurati, gettando le basi non solo dell’Esistenzialismo artistico ma anche dell’importanza del movimento, della naturalezza delle figure che non dovevano più sembrare in posa immobile bensì colte nell’istante del pensiero e dell’azione seguita alla riflessione; tra le opere più rappresentative e note del maestro di fine Ottocento, Il pensatore rappresenta l’atteggiamento dell’uomo di quel periodo a cavallo tra due secoli, destabilizzato da ciò che stava velocemente accadendo intorno a sé cambiando per sempre il mondo così come conosciuto. Allo stesso modo, il quasi contemporaneo Adolfo Wildt, che tuttavia rinunciò alla rappresentazione dei corpi dedicandosi ai busti e ai volti, ampliò il concetto esistenzialista della necessità di narrare l’interiorità umana, le angosce, le paure, le sofferenze che venivano rappresentate attraverso volti distorti, quasi liquefatti, come se l’aspetto esteriore dovesse corrispondere a quello interiore così come da linee guida dell’Espressionismo. Nell’evolversi del Ventesimo secolo vi fu un ampliamento delle tematiche esistenzialiste che si avvalsero di un’evoluzione di quel Simbolismo del secolo precedente riadattato agli studi sulla psiche umana svolti da Sigmund Freud dando vita così al Surrealismo che, anche nella scultura unì il mondo reale a quello immaginario, onirico, da cui si generarono figure inquietanti e irreali tanto quanto lo erano gli incubi che appartenevano all’uomo di quel periodo a metà tra le due guerre; la fragilità umana, la sua incapacità di mantenersi in piedi contro gli eventi travolgenti che doveva affrontare furono il tratto distintivo di uno dei maggiori esponenti della scultura del Novecento; parlo ovviamente di Alberto Giacometti le cui sottili silhouette umane esprimevano tutta la difficoltà del vivere, le insicurezze e la debolezza dell’uomo di fronte alle circostanze che si susseguivano.

Lo scultore veneto Ferruccio Tessarollo, innovatore dal punto di vista dell’approccio alla materia, fonde l’Esistenzialismo al Surrealismo Metafisico per dare origine a opere di forte impatto soprattutto perché inducono l’osservatore a riflettere su tutto ciò che vi è oltre l’immagine da lui raccontata; tutto ha un significato più profondo, ogni elemento di un’opera, ogni figura rappresentata assume il senso di una metafora, di un qualcosa su cui il fruitore è chiamato a riflettere, a meditare ma anche ad associare quelle sensazioni espresse dall’artista alle proprie, quelle su cui fa fatica a soffermarsi perché spesso fuggire dalla realtà, dalla presa di coscienza, dal dolore, è più semplice che affrontarlo.

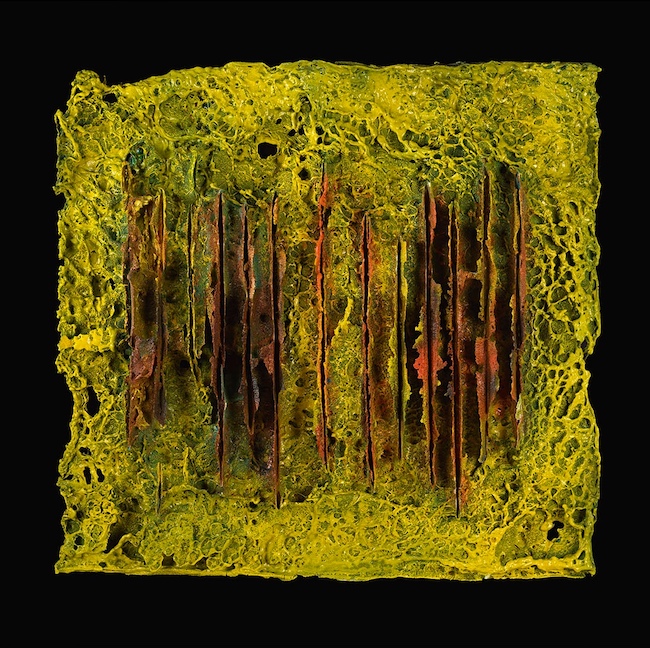

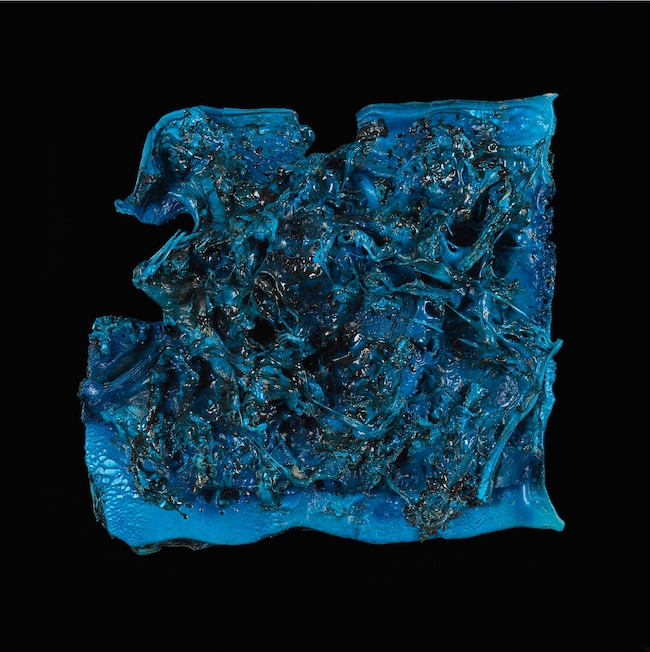

Non solo scultore, Ferruccio Tessarollo affronta anche la pittura e lo fa in maniera fortemente materica, quasi come se l’immagine dovesse costituire un esperimento conoscitivo, di scoperta delle infinite possibilità dei materiali utilizzati, una sapiente mescolanza tra una particolare resina abitualmente utilizzata come materiale isolante in edilizia, e gli elementi naturali come l’acqua e il fuoco, con cui agisce sulla resina dando vita a bruciature, estroflessioni, pigmentazioni che lo avvicinano all’Informale Materico in cui in concetto dell’atto esecutivo diventa prioritario sull’emozione, malgrado quelle medesime azioni di Tessarollo siano in grado di scuotere le corde interiori dell’osservatore.

E proprio per sottolineare l’esperimento, quel desiderio di misurarsi in maniera quasi primordiale con la materia, l’artista sceglie di non dare titoli alle sue opere pittoriche, denominandole tutte Texture che poi contraddistingue con un numero; ciò che emerge è la perpetua modificazione della realtà, quell’essere qualcosa, e subito dopo qualcos’altro che viene osservato in un’apparenza fluttuante, quasi come se l’opera non solo andasse a cercare la terza dimensione spingendosi verso l’esterno, ma rifiutasse anche di attenersi ai limiti imposti dalla tela, fuoriuscendo dai bordi netti per ondularsi in un mondo a metà tra la durezza della materia e la fluidità apparente che lo sguardo riceve.

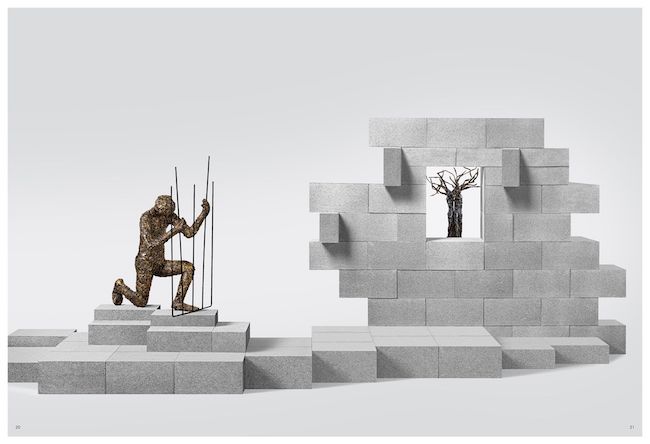

Per quanto riguarda le sculture Ferruccio Tessarollo, confermando il suo animo sperimentatore, utilizza anche in questo caso il polistirene estruso, la medesima resina delle pittosculture, modellandolo però in maniera differente, forgiandolo, piegandolo, manipolandolo fino a farlo diventare simile al ferro, per assecondarlo alle forme che desidera raccontare, quelle a lui necessarie a esprimere il concetto, la metafora, lo spunto di riflessione che intende mettere in luce nell’opera che si appresta a realizzare.

Nella scultura Solitudine Tessarollo pone l’uomo in posizione a metà tra il pensare, riferendosi dunque a Rodin pur attualizzando il gesto alle incertezze del vivere attuale, e la disperazione di non riuscire a interagire, di non essere in grado di trovare una mano, un sostegno, in quel percorso solitario che è l’esistenza in cui, pur trovandosi in mezzo alla moltitudine ciò che emerge con chiarezza è la sensazione di essere incredibilmente soli; la scala rappresenta da un lato il desiderio umano di tendere verso il massimo, verso il cielo, dall’altro però l’inevitabile presa d’atto che un cammino di conoscenza, di evoluzione, presuppone difficoltà e necessità di seguire una strada che solo in pochi affrontano.

In Resilienza invece riprende il tema della fragilità umana tanto cara a Giacometti pur volgendola al positivo poiché la forza interiore, la coriacea capacità di resistere alle avversità è tutto ciò che ha l’uomo moderno per non soccombere agli eventi, alle circostanze a volte negative, con cui deve fare i conti; il fascino di questa opera consiste in quella dissolvenza, quel vento degli accadimenti che pur tentando di trascinare via la donna protagonista tuttavia non riesce, perché lei è determinata ad attendere che quella lieve tempesta passi e che possa tornare presto a camminare verso il suo obiettivo, il suo sogno mai dimenticato, malgrado tutto.

Nella scultura Unione Tessarollo sottolinea quanto invece la coppia possa costituire una forza molto più potente di qualsiasi altra, al punto di generare una radice solida, un nido all’interno del quale le due parti si sentono protette dal sentimento reciproco e grazie al quale sono in grado di affrontare, insieme, le avversità esterne e gli alti e bassi della vita. L’uomo e la donna sono infatti posti all’interno del grande tronco che rappresenta l’amore, il desiderio di costruire, di percorrere insieme il cammino in grado di salvarli da quella solitudine che invece inevitabilmente assale chi sceglie, o è costretto, ad affrontare la vita senza avere qualcuno accanto. Ferruccio Tessarollo nel corso della sua carriera ha partecipato a molte mostre collettive e a premi di pittura ricevendo riconoscimenti da parte del pubblico e degli addetti ai lavori; nel 2016 è stato il vincitore del concorso Arte a Palazzo a Bologna e del concorso Arte tra Cielo e Mare e ha ricevuto la menzione come Innovazione nell’Arte al Premio Internazionale Tiepolo Arte a Milano.

Marta Lock

FERRUCCIO TESSAROLLO-CONTATTI

Sito web: www.ferrucciotessarollo.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/FerruccioTessarolloUccio

https://www.facebook.com/FerruccioTessarolloArtist/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ferrucciotessarollo/

The sculptural existentialism of Ferruccio Tessarollo, when matter is moulded to the reflections of living

The questioning of the meaning of life, of the deepest impulses and the need to search for solid points of reference belong to the multi-faceted range of emotions with which contemporary man is confronted on a daily basis; art consequently cannot fail to represent the difficulties and inner anxieties that characterise the Twenty-first century as much as, for other objective circumstances, they did the Twentieth. As part of this introspective research, some artists remain within their own inner world, feeling the need to free up those energies that would otherwise be unexpressed, while others try to listen to and observe the surrounding reality, trying to give it an interpretation through their artistic production. Today’s protagonist chooses this second way to transmit to the viewer his point of view on everything that surrounds him and on which his gaze lingers precisely because its most hidden meaning is often ignored by most people.

Throughout the history of art, sculpture has taken on celebratory roles, representing a reality that was meant to appear majestic and regal, at least until the avant-garde broke down every canon of execution to enter a different field, that of sensations, of the unseen, of the mystery of existence that could not be revealed despite the efforts of human beings. Already in the previous century, Auguste Rodin, considered the father of modern sculpture, had placed the character and emotional thought of the figures he depicted at the centre of his artistic research, laying the foundations not only of artistic Existentialism but also of the importance of movement, of the naturalness of the figures, which should no longer appear to be posed motionless but caught in the instant of thought and action following reflection; one of the most representative and well-known works of the late 19th-century master, The Thinker represents the attitude of the man of that period at the turn of the century, destabilised by what was rapidly happening around him, changing the world as we know it forever.

Similarly, the almost contemporary Adolfo Wildt, who nevertheless renounced the representation of bodies by dedicating himself to busts and faces, expanded the existentialist concept of the need to narrate the human interiority, the anguish, the fears, the sufferings that were represented through distorted, almost liquefied faces, as if the exterior aspect had to correspond to the interior one, according to the guidelines of Expressionism. As the twentieth century evolved, existentialist themes were broadened, making use of an evolution of the Symbolism of the previous century adapted to the studies on the human psyche carried out by Sigmund Freud, thus giving rise to Surrealism which, even in sculpture, combined the real world with the imaginary, dreamlike universe, generating figures as disturbing and unreal as the nightmares of the people of that period between the two wars; human frailty, the inability to stand up to the overwhelming events he had to face, was the hallmark of one of the greatest exponents of twentieth-century sculpture, Alberto Giacometti of course, whose subtle human silhouettes expressed all the difficulties of living, man’s insecurities and weakness in the face of changing circumstances.

The Venetian sculptor Ferruccio Tessarollo, an innovator in his approach to materials, blends Existentialism with Metaphysical Surrealism to create artworks of great impact, especially because they prompt the observer to reflect on everything that lies beyond the image he is portraying; everything has a deeper meaning, every element of a work, every figure represented assumes the sense of a metaphor, of something on which the viewer is called upon to reflect, to meditate but also to associate those sensations expressed by the artist with his own, those on which he finds it difficult to dwell because often fleeing from reality, from awareness, from pain, is easier than facing it. Not only a sculptor, Ferruccio Tessarollo also tackles painting, and he does so in a strongly materic way, almost as if the image were to constitute a cognitive experiment, a discovery of the infinite possibilities of the materials used, a skilful mixture of a particular resin usually used as an insulating material in construction, and natural elements such as water and fire, with which he acts on the resin, creating burns, extroflexions and pigmentations that bring him closer to the Materic Informal style in which the concept of the act of painting takes priority over emotion, even though Tessarollo’s actions are capable of shaking the observer’s inner chords. And precisely to underline the experiment, that desire to measure himself in an almost primordial way with the material, the artist chooses not to give titles to his paintings, calling them all Texture, which he then distinguishes with a number; what emerges is the perpetual modification of reality, that being something, and immediately afterwards something else, which is observed in a fluctuating appearance, almost as if the work not only seeks the third dimension by pushing outwards, but also refuses to abide by the limits imposed by the canvas, escaping from the clear edges to undulate in a world halfway between the hardness of the material and the apparent fluidity that the eye receives. About the sculptures Ferruccio Tessarollo, confirming his experimental spirit, also in this case uses extruded polystyrene, the same resin as in the pictosculptures, modelling it in a different way, forging it, bending it, manipulating it until it becomes similar to iron, in order to adapt it to the shapes he wants to tell, the ones he needs to express the concept, the metaphor, the food for thought he wants to highlight in the artwork he is about to create.

In the sculpture Solitudine (Lonelyness), Tessarollo places man in a position somewhere between thinking, thus referring to Rodin while updating the gesture to the uncertainties of present-day life, and the desperation of not being able to interact, of not being able to find a hand, a support, in that solitary path that is existence in which, despite finding oneself in the midst of the multitude, what clearly emerges is the sensation of being incredibly alone; on the one hand, the ladder represents the human desire to strive towards the highest, towards the heavens, but on the other hand it represents the inevitable realisation that a path of knowledge and evolution presupposes difficulties and the need to follow a route that only a few can follow. In Resilienza (Resilience), on the other hand, takes up the theme of human frailty so dear to Giacometti, while turning it into a positive one, since inner strength, the tough capacity to resist adversity, is all that modern man has to keep from succumbing to the events and sometimes negative circumstances he has to deal with; the charm of this sculpture lies in that fading, that wind of events which, although it tries to drag the woman protagonist away, nevertheless does not succeed, because she is determined to wait for that slight storm to pass and that she will soon be able to walk again towards her goal, her never forgotten dream, despite everything. In the sculpture Unione (Union) Tessarollo emphasises how the couple can be a much more powerful force than any other, to the point of generating a solid root, a nest within which the two parties feel protected by mutual feeling and thanks to which they are able to face external adversities and the ups and downs of life together. Man and woman are in fact placed inside the great trunk that represents love, the desire to build, to walk together along the path capable of saving them from that loneliness that inevitably assails those who choose, or are forced, to face life without having someone beside them. Over the course of his career, Ferruccio Tessarollo has taken part in many group exhibitions and painting prizes, receiving recognition from the public and the experts; in 2016 he was the winner of the Arte a Palazzo competition in Bologna and the Arte tra Cielo e Mare competition, and received a mention for Innovation in Art at the Tiepolo Arte International Prize in Milan.