Il fluire delle sensazioni all’interno dell’individuo va a mescolarsi con le circostanze che si susseguono rendendo necessario, in particolar modo per alcuni artisti, un percorso di liberazione, di esternazione di tutta quell’emozionalità che non può fare a meno di fuoriuscire pur senza trovare un linguaggio razionale adeguato a essere espressa in tutta la sua complessità. Dunque l’approccio informale diviene quello strumento attraverso cui l’istinto non trova ostacoli, e dove l’inspiegabile riesce a coniugarsi a una specifica tonalità cromatica, a una pennellata intensa o più leggera sulla base della sensazione che si ha bisogno di esprimere, e in cui la figurazione costituirebbe solo un ostacolo alla spontaneità narrativa legata all’inconscio e all’impulso. La protagonista di oggi sceglie la dimensione della non forma per narrare le sensazioni profonde che si trova a vivere nella sua quotidianità trasformando la tela in testimonianza di una sensibilità emotiva che talvolta ha bisogno di gridare, mentre altre preferisce un racconto sottovoce da cui lasciar emergere piccole evocazioni di immagini connesse alle riflessioni protagoniste.

Intorno alla metà del Ventesimo secolo, quando l’onda rigorosa dell’Arte Astratta del primo ventennio, in cui gli autori avevano cercato di affermare la superiorità del gesto artistico su qualsiasi soggettivismo dell’autore così come sulla riproduzione di immagini riscontrabili nella realtà quotidiana, emerse un’inedita esigenza espressiva che mettesse l’esecutore di un’opera e il suo sentire in primo piano. Questa nuova onda stilistica partì negli Stati Uniti, dalla caparbietà di artisti come Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willelm de Koonig e Arshile Gorky che combatterono contro il sistema arte dell’epoca da cui furono inizialmente rifiutati, e poi si estese anche al continente europeo con variazioni e personalizzazioni sulla base del paese di provenienza degli artisti e dell’interpretazione soggettiva dello stile. In effetti l’unica linea guida dell’Espressionismo Astratto, questo il nome della nuova corrente pittorica, era che l’emozionalità e le sensazioni dell’autore permeassero l’opera creando così un canale di comunicazione inconscio con l’osservatore che si sentiva avvolto, travolto, o inconsapevolmente attratto da una tela. Stabilita l’assoluta libertà esecutiva, cromatica e persino formale, i protagonisti del movimento mostrarono pertanto un atteggiamento differente nei confronti del gesto esecutivo e anche dell’interpretazione cromatica, così il Dripping di Jackson Pollock in cui l’Action Painting era una fase dell’opera stessa, era perfettamente affine alla sua personalità tanto quanto le atmosfere silenziose e meditative del Color Field di Mark Rothko erano assolutamente calzanti al suo atteggiamento riflessivo e calmo. Non solo, purché fossero espressione delle profondità dell’animo, nel movimento erano accettati anche quegli autori che non rinunciarono mai completamente alla figurazione, come nel caso di Arshile Gorky in cui erano evidenti le influenze europee e il legame con la poetica espressiva del fondatore dell’Arte Astratta Vassily Kandinsky, o di Philip Guston le cui stilizzazioni rendevano le opere intense, confuse ma allo stesso tempo attrattive per l’impatto che riuscivano a generare nell’osservatore. Gli interpreti dell’Espressionismo Astratto in Europa modificarono alcune caratteristiche introducendo anche l’utilizzo della materia, che veniva contorta, bruciata, liquefatta per sottolineare la forza e la concretezza del sentire interiore, come nelle tele di Alberto Burri, oppure utilizzando spatole e pennelli di grandi dimensioni per stendere strati di colore, poi raschiati via o sovrapposti in modo da creare texture complesse e stratificate come nelle celeberrime opere di uno dei maggiori interpreti contemporanei della corrente, quel Gerard Richter che ha fatto dell’ambivalenza tra impulso e controllo il segreto del suo successo. L’artista Rabia Kadmiri, nata a Casablanca e trasferitasi in Germania dopo aver conseguito il diploma in design industriale, opta per l’Espressionismo Astratto come manifestazione di un’essenza pittorica che sente affine alla sua personalità, a quell’attitudine a lasciarsi avvolgere completamente dalle percezioni che riceve dagli impulsi esterni e che hanno bisogno di trasformarsi in voce senza parole, in narrazione senza le briglie della logica, perché tutto ciò che conta per lei è l’immediatezza del gesto pittorico.

Le tonalità sono note musicali che si conformano alle emozioni, vanno a legarsi direttamente ai ricordi, al sentire, a tutto ciò che ha assorbito nella sua vita quotidiana e che deve essere immortalato sulla tela; ogni colore corrisponde dunque a una specifica emozione e il loro accostamento svela lo stato d’animo di Rabia Kadimiri nel momento in cui si è trovata nella circostanza che l’ha spinta a prendere in mano i pennelli per iniziare a dipingere.

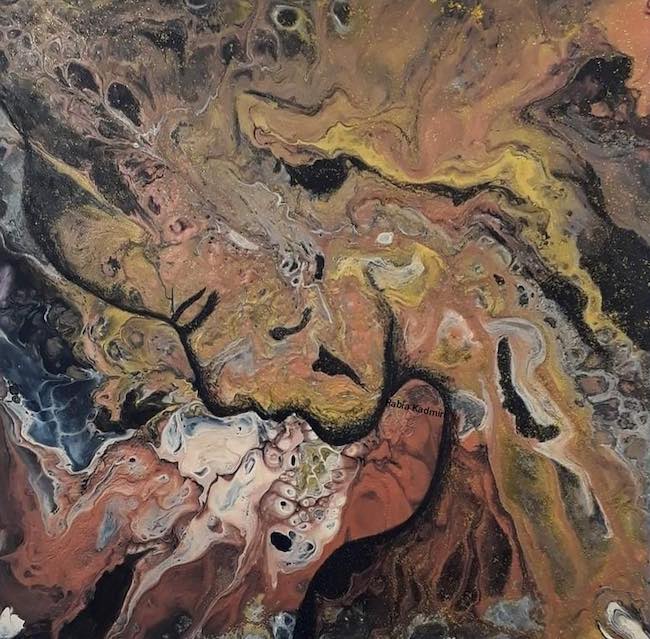

In qualche tela però il puro istinto che contraddistingue le sue opere lascia spazio a un sottile sussurro di consapevolezza, quello in virtù del quale l’autrice lascia emergere una sottile figurazione, come se si manifestasse dal profondo del sentire per tratteggiarsi sommessamente dal caos dell’Astrattismo che la circonda; questo approccio è particolarmente evidente in Ein Genauer Blick (Uno sguardo più attento), che sembra essere un invito all’osservatore ad andare a fondo rispetto al primo impatto iniziale, introducendo così un concetto quasi surrealista, di cui la presenza di occhi decontestualizzati è una delle caratteristiche peculiari.

In questo lavoro i colori sono quasi graffiati, sembrano voler attrarre l’attenzione sull’attitudine moderna a trascurare i dettagli, a dare solo occhiate fugaci al generale dimenticando il particolare che costituisce il successivo livello di realtà su cui invece si focalizza Rabia Kadmiri attraverso l’occhio e la bocca lasciati in secondo piano eppure in grado di prendere completamente il sopravvento nel momento in cui si compie lo sforzo di approfondimento richiesto. In qualche modo l’opera ha una doppia valenza, quello del richiamo della propria coscienza che emerge dal caos esterno, e quello della sollecitazione a considerare con maggiore attenzione ciò che ruota intorno all’essere umano mettendo così in primo piano le emozioni di chi si incontra per caso e che diversamente resterebbe invisibile.

E infatti nella tela Geist der Welt (Spirito del mondo) sembra che l’autrice si ponga in posizione di ascolto di tutte quelle energie che scorrono intorno all’essere umano senza che egli ne sia consapevole, le libera attraverso i colori che sembrano essere semi di vita dei quattro elementi – acqua, aria, terra e fuoco – che si mescolano tra loro per dar vita a quel miracolo che è la natura, in tutte le sue sfaccettature, e l’esistenza stessa della terra e di chiunque la abiti.

In questo lavoro sembra essere presente un costante caos creativo, un perpetuo fluire e mescolarsi per dissolversi e rifondersi, ancora e ancora, svelando all’osservatore quanto tutto ciò che alla mente razionale appare dominato dalla logica e dal rigore, in realtà sia generato dalla pura scintilla di casualità che tutto travolge e al contempo tutto spiega, come se da quell’impulso si generasse il senso della vita stessa. Die Hölle (L’inferno), al contrario, racconta del luogo più brutto, quello da cui chiunque vorrebbe fuggire pur essendo costretto a fronteggiarlo, a percorrerlo, a causa di circostanze imprevedibili che non possono in alcun modo essere evitate; dunque l’inferno di cui parla Rabia Kadimiri è metaforico, appartiene alla vita di chiunque si trovi ad affrontare un episodio spiacevole, una sofferenza fisica o dell’anima, la perdita di qualcuno o di qualcosa di importante.

Eppure i colori utilizzati dall’autrice non sono cupi, non sono scuri e lugubri come ci si aspetterebbe, al contrario il chiarore e le tonalità scelte sembrano suggerire che da quel luogo, inteso come punto di dolore, è possibile trovare una via d’uscita, è possibile riprendersi, rialzarsi e tendere verso la luce, quindi il messaggio è in ogni caso di speranza, una prospettiva positiva in virtù della quale il cammino di risalita sembra meno difficile. In Eine magische Nacht (Una notte magica) invece Rabia Kadmiri lascia fuoriuscire dalle tonalità terree dell’Espressionismo Astratto una sottile figurazione, il profilo di una donna sognante che ricorda un frangente piacevole appartenente al suo scrigno emotivo, o forse immersa nell’immaginare qualcosa che sta desiderando con tutta se stessa e che ha bisogno di chiedere alle stelle che possano trasformarlo in realtà. Il volto è evanescente, si perde dentro le tonalità sfumate con cui l’autrice racconta la notte, mai buia bensì illuminata dalla luna, quasi a voler cullare la fantasia della protagonista sussurrandole che tutto può essere possibile.

Rabia Kadmiri nel corso della sua carriera artistica è stata premiata come Artista dell’Anno nel 2020 in Italia e ha ricevuto riconoscimenti e onorificenze dall’Egitto e dal Marocco; ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre collettive a Bonn, Münster, Friburgo, al Museo Bauhaus di Dessau, in Germania, e al Cairo in Egitto.

RABIA KADMIRI-CONTATTI

Email: zollarachid164@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/RobyArt2/about

Instagram: www.instagram.com/kadmiri_art/

Abstract Expressionism by Rabia Kadimiri, between overwhelming emotions and whispers of figuration

The flow of sensations within the individual goes to mingle with the circumstances that follow one another, making necessary, especially for some artists, a path of liberation, of externalization of all that emotionality that cannot help but spill out while not finding a rational language adequate to be expressed in all its complexity. So the informal approach becomes that instrument through which instinct finds no obstacles, and where the inexplicable succeeds in conjugating itself to a specific chromatic tonality, to an intense or lighter brushstroke on the basis of the sensation one needs to express, and in which figuration would only constitute an obstacle to the spontaneous narrative linked to the unconscious and the impulse. Today’s protagonist chooses the dimension of non-form to narrate the profound sensations she experiences in her everyday life, transforming the canvas into a testimony of an emotional sensibility that sometimes needs to shout, while at others prefers a subdued narrative from which letting emerge small evocations of images connected to the protagonist’s reflections.

Around the middle of the twentieth century, when the rigorous wave of Abstract Art of the first two decades, in which authors had sought to assert the superiority of the artistic gesture over any subjectivism of the author as well as the reproduction of images found in daily reality, emerged an unprecedent expressive need that would put the author of an artwork and his feeling in the foreground. This new stylistic wave started in the United States, from the stubbornness of artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willelm de Koonig and Arshile Gorky who fought against the art system of the time by which they were initially rejected, and then extended to the European continent with variations and personalization based on the artists’ country of origin and subjective interpretation of style. In fact, the only guideline of Abstract Expressionism, this was the name of the new pictorial current, was that the author’s emotionality and feelings permeated the work, thus creating an unconscious channel of communication with the viewer who felt enveloped, overwhelmed, or unconsciously drawn to a canvas. Having established absolute executive, chromatic, and even formal freedom, the protagonists of the movement therefore displayed a different attitude toward executive gesture and even chromatic interpretation, so the Dripping of Jackson Pollock in which Action Painting was a phase of the work itself, was perfectly akin to his personality as much as the quiet and meditative atmospheres of Mark Rothko‘s Color Field were absolutely fitting to his reflective and calm attitude.

Not only that, as long as they were an expression of the depths of the soul, were also accepted in the movement those authors who never completely renounced figuration, as in the case of Arshile Gorky in whom European influences and the link with the expressive poetics of the founder of Abstract Art Vassily Kandinsky were evident, or Philip Guston whose stylizations made the works intense, confusing but at the same time attractive because of the impact they managed to generate in the viewer. The interpreters of Abstract Expressionism in Europe modified certain characteristics by also introducing the use of matter, which was twisted, burned, liquefied to emphasize the strength and concreteness of inner feeling, as in Alberto Burri‘s canvases, or by using large spatulas and brushes to lay down layers of color, then scraped away or overlapped to create complex, stratified textures as in the celebrated artworks of one of the greatest contemporary interpreters of the current, that Gerard Richter who made the ambivalence between impulse and control the secret of his success.

The artist Rabia Kadmiri, who was born in Casablanca and moved to Germany after graduating in industrial design, opts for Abstract Expressionism as a manifestation of a pictorial essence that she feels is akin to her personality, to that aptitude for allowing herself to be completely enveloped by the perceptions she receives from external impulses and that need to be transformed into voice without words, into narration without the reins of logic, because all that matters to her is the immediacy of the pictorial gesture. The hues are musical notes that conform to emotions, they go to tie directly to memories, to feeling, to all that she has absorbed in her daily life and that needs to be immortalized on canvas; each color thus corresponds to a specific emotion and their juxtaposition reveals Rabia Kadimiri‘s state of mind at the moment she found herself in the circumstance that prompted her to pick up the brushes to start painting. In a few canvases, however, the pure instinct that distinguishes her works gives way to a subtle whisper of awareness, the one by virtue of which the author allows to emerge a subtle figuration, as if manifesting itself from the depths of feeling to sketch subtly out of the chaos of Abstractionism that surrounds it; this approach is particularly evident in Ein Genauer Blick (A Closer Look), which seems to be an invitation to the viewer to go deeper than the initial glimpse, thus introducing an almost surrealist concept, of which the presence of decontextualized eyes is one of the distinguishing features.

In this artwork the colors are almost scratched, they seem to want to draw attention to the modern attitude of neglecting details, of giving only fleeting glances at the general forgetting the particular that constitutes the next level of reality on which instead Rabia Kadmiri focuses through the eye and mouth left in the background yet able to take over completely the moment the required effort of deepening is made. In some ways the work has a double significance, that of the call of one’s own consciousness emerging from the external chaos, and that of the solicitation to consider more carefully what revolves around the human being thus foregrounding the emotions of those one meets by chance and who would otherwise remain invisible. And in fact in the canvas Geist der Welt (Spirit of the World) the author seems to place herself in a position of listening to all those energies that flow around the human being without him being aware of them, frees them through colors that seem to be seeds of life from the four elements-water, air, earth and fire-that mix together to give birth to the miracle that is nature, in all its facets, and the very existence of the earth and anyone who inhabits it. In this work there seems to be a constant creative chaos, a perpetual flow and mixing only to dissolve and re-merge, again and again, revealing to the observer how everything that to the rational mind appears dominated by logic and rigor is actually generated by the pure spark of chance that overwhelms and at the same time explains everything, as if from that impulse was generated the meaning of life itself.

Die Hölle (Hell), on the contrary, tells of the ugliest place, the one from which anyone would like to escape despite being forced to face it, to walk through it, because of unpredictable circumstances that cannot be avoided in any way; thus, the hell Rabia Kadimiri speaks of is metaphorical, it belongs to the life of anyone who faces an unpleasant episode, a physical or soul suffering, the loss of someone or something important. Yet the colors used by the author are not gloomy, they are not dark and dismal as one would expect, on the contrary, the lightness and hues chosen seem to suggest that from that place, understood as a point of pain, it is possible to find a way out, it is possible to recover, to get back up and tend toward the light, so the message is in any case one of hope, a positive perspective by virtue of which the path of ascent seems less difficult. In Eine magische Nacht (A Magical Night), on the other hand, Rabia Kadmiri lets out of the earthy tones of Abstract Expressionism a subtle figuration, the profile of a dreamy woman recalling a pleasant juncture belonging to her emotional treasure chest, or perhaps immersed in imagining something she is longing for with all her being and needs to ask the stars that they may turn it into reality. The face is evanescent, lost within the nuanced tones with which the author narrates the night, never dark but illuminated by the moon, as if to lull the protagonist’s imagination by whispering to her that anything can be possible. Rabia Kadmiri in the course of her artistic career has been awarded Artist of the Year in 2020 in Italy and has received awards and honors from Egypt and Morocco; she has to her credit participation in group exhibitions in Bonn, Münster, Freiburg, the Bauhaus Museum in Dessau, Germany, and Cairo, Egypt.