Il percorso di vita che alcuni autori intraprendono è quasi un fondamento essenziale per permettere loro di assorbire tutte quelle esperienze visive, olfattive e di vita che poi sono funzionali a strutturare non solo il loro approccio alla realtà in cui di volta in volta si trovano, ma anche al loro modo di intendere e manifestare la propria inclinazione creativa. Se questo tipo di atteggiamento assorbente-emanante si orienta verso uno stile prevalentemente figurativo, a quel punto l’oggettività diventa persino limitante per lasciar fluire un’interiorità che ha bisogno di porsi sul livello della percezione, dell’intuizione e dell’emotività che sono alla base dell’arte. Questo è esattamente il percorso compiuto dalla protagonista di oggi, la quale mescola le caratteristiche di due tra i maggiori movimenti figurativi del secolo scorso per elaborare un suo linguaggio eclettico ma con la base unificante del diffondere le sensazioni ricevute durante la fase della contemplazione visiva.

Gli anni a cavallo tra la fine dell’Ottocento e l’inizio del Novecento hanno visto la nascita e poi la radicale trasformazione di stili pittorici innovativi, contrapposti a quelli più accademici e tradizionali i quali, per sopravvivere a quel vento di cambiamento, hanno dovuto snaturare la propria essenza per andare verso un’inarrestabile atmosfera avanguardista alla quale non era possibile opporsi. L’osservazione del mondo circostante all’autore si era già, con il Realismo di metà del Diciannovesimo secolo, sensibilizzata verso il popolo, verso una società lontana dai salotti aristocratici ma di fatto base imprescindibile dell’economia mondiale, poiché era grazie alla forza lavoro che la borghesia poteva continuare ad aumentare i suoi profitti. Pertanto i ritratti di persone appartenenti a classi poco abbienti di Jean-François Millet e Gustave Courbet lasciavano emergere anche un’anima, un punto di vista empatico degli autori che nell’arte precedente sembrava essere assente. Qualche decennio dopo esplose il desiderio in alcuni artisti di mettere al centro l’uomo con le sue emozioni più o meno dirompenti, con le sue fragilità, con i pensieri che di diffondevano sulla tela in maniera rivoluzionaria, rinunciando addirittura a ogni attinenza all’osservato sia dal punto di vista cromatico che da quello figurativo pur di dare la priorità alla forza emozionale. Furono queste le linee guida principali dell’Espressionismo, evoluzione delle prime teorie dei Fauves francesi, interpretate e declinate sulla base del sentire del singolo autore ma anche su quella del paese di provenienza di ciascun artista; in Austria con Egon Schiele a prevalere fu la deformazione fisica pur legata a una scelta di colori vicini alla realtà che poi però se ne distaccava per la semplificazione narrativa e stilistica dell’eliminazione della prospettiva, del chiaroscuro e di tutte le regole accademiche realiste.

In Francia con Marc Chagall si andò invece verso il sogno, verso l’innocenza e la semplicità che diveniva esortazione per l’osservatore a vivere mettendo al centro le piccole emozioni, la quotidianità che solo attraverso uno sguardo intenso e profondo poteva assumere quel carattere di straordinarietà manifestato in ognuna delle sue tele. Ma anche il movimento della Nuova Oggettività tedesca restò, a differenza di altri esponenti dell’Espressionismo europeo, vicino alla realtà osservata, prendendo la deformazione e la caratterizzazione stilizzata dei personaggi che contraddistingueva sia Schiele che Chagall. Il cammino di convergenza tra i due stili pittorici apparentemente distanti, il Realismo e l’Espressionismo, era ormai avviato anche perché gli stravolgimenti della società europea di quel tempo, con le due guerre e le scoperte tecnologiche che sembravano spersonalizzare l’uomo avvicinandolo a un meccanismo della catena di montaggio, spingevano gli artisti verso un nuovo umanesimo che doveva mettere al centro le emozioni e i pensieri. La sintesi di questo approccio si rese evidente con il Realismo Magico, dove però la parte percettiva e interpretativa ruotava intorno al mistero, all’enigma, a quel sentire che non può essere colto dall’autore. L’artista romana Stefania Del Papa va a generare una sua personale fusione dei due stili finora menzionati che si svelano attraverso una figurazione legata all’osservazione ma poi traslata dall’interiorità, da un’anima da sempre abituata ad ascoltare, vedere e svelare abitudini, modi di vivere, colori e sapori differenti da quelli in cui è nata grazie al fatto di aver vissuto e studiato negli Stati Uniti, a Washington e a New York.

La sua attitudine all’empatia, seppur innata, viene stimolata e sviluppata proprio attraverso il viaggio, la conoscenza di qualcosa di diverso da sé e dal proprio mondo, e all’evoluzione che inevitabilmente si genera nel momento in cui l’essere umano, e nel caso specifico l’artista, è costretto a mettersi in discussione, a entrare in contatto con usi e costumi diversi.

Dal punto di vista stilistico dunque, malgrado una figurazione molto vicina al realismo anche per l’utilizzo della luce e per la scelta di scenari visivamente individuabili, la tendenza più evidente di Stefania Del Papa è quella di scendere in profondità, di svelare un intimismo che fuoriesce non solo dalle opere in cui a essere protagonista è l’essere umano, e in particolare la donna, bensì anche in quelle dove sceglie di raccontare un paesaggio, un animale, l’esecuzione di un’altra arte come il ballo, perché è in virtù del suo sentire che può scendere a fondo, andare oltre il visibile e raccontare l’immagine osservata fondendola appunto alla soggettività interpretativa.

Il suo tratto è più deciso e contemplativo quando rappresenta i paesaggi, che tuttavia sembrano appartenere più al suo cuore e allo scrigno della sua memoria che non a luoghi esistenti o individuabili, o più in generale la natura che ritrae in maniera spontanea senza voler raggiungere una perfezione descrittiva che non le sarebbe congeniale, ma poi diviene evanescente, quasi etereo e dunque fortemente espressionista, quando a essere protagoniste sono le donne. Probabilmente in quest’ultimo caso riesce a percepirne l’essenza, le domande senza risposta, i dubbi, le perplessità ma anche la forza e l’energia, che appartengono indissolubilmente al mondo femminile, che Stefania Del Papa conosce bene e che ha potuto approfondire e portare alla luce proprio attraverso l’arte.

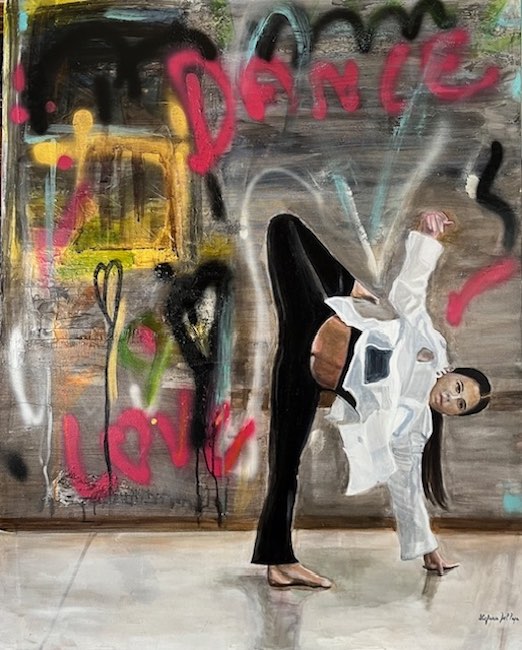

Break Free è un’opera emblematica poiché qui l’autrice trasforma la forza liberatoria del ballo in simbolo della capacità della donna di ascoltare l’anima, di permettere all’istinto di guidare un’evoluzione che può compiersi solo dopo aver lasciato andare tutti i limiti che fino a quel momento l’avevano ingabbiata impedendole di scoprirsi. Qui la figurazione è dunque miniaturizzata, il corpo della donna che esegue il passo di danza è sottoesposto rispetto all’esplosione cromatica che contraddistingue lo sfondo predominante sulla tela, e questo è funzionale a guidare l’osservatore a considerare più il senso del titolo che non quello visivo su cui si concentrerebbe lo sguardo, quello cioè della ballerina.

In Dawn la parola è lasciata alla natura, a un panorama incontaminato di dolci colline e vallate in cui a predominare è il verde intenso dei prati e dell’erba nel periodo primaverile quando appunto tutto è pronto a rinascere dopo il freddo dell’inverno; l’alba può essere quella più letterale del sorgere del sole, ma anche quella simbolica di una nuova consapevolezza, di una rinascita interiore che non può non sentirsi accolta da un paesaggio tanto sereno e rilassante. Sullo sfondo le luci di piccoli paesi che rappresentano una civiltà esistente ma distante dal singolo, quasi Stefania Del Papa volesse suggerire che solo dopo aver effettuato un cammino di approfondimento e di scoperta del sé si può avvicinarsi con l’armatura della propria forza anche a un mondo comunitario che troppo spesso tende invece ad omologare e a soffocare l’individualità.

Flowering appartiene alle opere più intimiste, quelle dove il Realismo si fonde con l’Espressionismo da cui emerge l’impalpabilità legata all’anima, a un sentire che Stefania Del Papa ascolta, comprende e poi rimanda sulla tela, come se la protagonista le chiedesse di andare oltre alla patina superficiale, come se la sua fosse una silenziosa aspettativa di essere vista davvero. Il significato del titolo, fioritura, ancora una volta appare simbolico del senso reale del ritratto perché al di là dei fiori con cui l’autrice orna i capelli della ragazza, a colpire è lo sguardo fresco, inconsapevole della sua bellezza e forse persino insicuro nel sapere di dover intraprendere un percorso di crescita complesso, come se il semplice fiorire avesse bisogno di una sostanza costituita da esperienze, da cadute, da errori ma anche dalla capacità di superarli. La narrazione di Stefania Del Papa mostra un’empatia quasi materna, sembra voler rassicurare la giovane e al contempo stimolarla a non fermarsi mai solo all’inseguimento dell’apparenza bensì a coltivare quella sostanza che rimarrà anche quando poi, l’inevitabile corso della vita, la condurrà a sfiorire e a perdere la bellezza che ora le appartiene.

Stefania Del Papa scopre fin da bambina la sua anima artistica e frequenta corsi di disegno e pittura sia a New York che a Roma, come la Scuola San Giacomo di Arti Ornamentali, e ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre collettive su tutto il territorio nazionale.

STEFANIA DEL PAPA-CONTATTI

Email: steffispaintings@gmail.com

Sito web: www.stefaniadelpapa.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61573656642466

Instagram: www.instagram.com/steffidp_art/

Stefania Del Papa’s Realistic Expressionism, when art becomes a path to freedom for the soul

The path that some artists take in life is almost an essential foundation that allows them to absorb all those visual, olfactory, and life experiences that are then functional in structuring not only their approach to the reality in which they find themselves from time to time, but also their way of understanding and expressing their creative inclination. If this type of absorbing-emanating attitude is oriented towards a predominantly figurative style, then objectivity becomes limiting to the flow of an inner self that needs to place itself on the level of perception, intuition, and emotion that are the basis of art. This is exactly the path taken by today’s protagonist, who combines the characteristics of two of the major figurative movements of the last century to develop her own eclectic language, but with the unifying basis of spreading the sensations received during the phase of visual contemplation.

The years between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century saw the birth and then the radical transformation of innovative painting styles, contrasted with the more academic and traditional ones which, in order to survive that wind of change, had to distort their essence to move towards an unstoppable avant-garde atmosphere that could not be opposed. The author’s observation of the world around him had already, with the Realism of the mid-19th century, become sensitized to the people, to a society far removed from aristocratic salons but in fact an essential basis of the world economy, since it was thanks to the labor force that the bourgeoisie could continue to increase its profits. Therefore, the portraits of people belonging to the lower classes by Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet also revealed a soul, an empathetic point of view on the part of the artists that seemed to be absent in previous art. A few decades later, some artists felt a strong desire to focus on people and their more or less disruptive emotions, their fragility, and their thoughts, which they spread across the canvas in a revolutionary way, even giving up any connection to what they were observing, both from a chromatic and figurative point of view, in order to prioritize emotional power.

These were the main guidelines of Expressionism, an evolution of the early theories of the French Fauves, interpreted and expressed based on the feelings of the individual author, but also on those of the country of origin of each artist. In Austria, with Egon Schiele, prevailed physical deformation albeit linked to a choice of colors close to reality, which then detached from it due to the narrative and stylistic simplification of the elimination of perspective, chiaroscuro, and all the academic rules of Realism. In France, Marc Chagall moved towards dreams, innocence, and simplicity, which became an exhortation for the observer to live by focusing on small emotions and everyday life, which only through an intense and profound gaze could take on the extraordinary character manifested in each of his canvases. But even the German New Objectivity movement, unlike other exponents of European Expressionism, remained close to observed reality, taking the deformation and stylized characterization of the characters that distinguished both Schiele and Chagall. The convergence between the two seemingly distant pictorial styles, Realism and Expressionism, was now underway, partly because the upheavals in European society at that time, with the two wars and technological discoveries that seemed to depersonalize man bringing him closer to an assembly line mechanism, pushed artists towards a new humanism that had to focus on emotions and thoughts.

The synthesis of this approach became evident with Magical Realism, where, however, the perceptive and interpretative part revolved around mystery, enigma, and that feeling that cannot be grasped by the author. The Roman artist Stefania Del Papa creates her own personal fusion of the two styles mentioned above, which are revealed through a figuration linked to observation but then translated from the interiority, from a soul that has always been accustomed to listening, seeing, and revealing habits, ways of life, colors, and flavors different from those in which she was born, thanks to having lived and studied in the United States, Washington and New York. Her innate capacity for empathy is stimulated and developed through travel, through the discovery of something different from herself and her own world, and through the evolution that inevitably occurs when human beings, and in this specific case artists, are forced to question themselves and come into contact with different customs and traditions.

From a stylistic point of view, therefore, despite a figurative style very close to Realism, also due to the use of light and the choice of visually identifiable scenarios, Stefania Del Papa‘s most evident tendency is to delve deeper, to reveal an intimacy that emerges not only from works in which human beings, and women in particular, are the protagonists, but also from those in which she chooses to depict a landscape, an animal, or the performance of another art form such as dance, because it is by virtue of her feelings that she can delve deeper, go beyond the visible and describe the image she observes, merging it with her interpretative subjectivity. Her style is more decisive and contemplative when she depicts landscapes, which, however, seem to belong more to her heart and the treasure chest of her memory than to existing or identifiable places, or more generally to nature, which she portrays spontaneously without seeking to achieve a descriptive perfection that would not suit her, but then it becomes evanescent, almost ethereal and therefore strongly expressionistic, when women are the protagonists.

In the latter case, she probably manages to perceive their essence, their unanswered questions, their doubts, their perplexities, but also their strength and energy, which belong inextricably to the female world, which Stefania Del Papa knows well and which she has been able to explore and bring to light through art. Break Free is an emblematic artwork because here the author transforms the liberating power of dance into a symbol of a woman’s ability to listen to her soul, to allow her instinct to guide an evolution that can only take place after letting go of all the limitations that had caged her until then, preventing her from discovering herself. Here, the figuration is miniaturized, the body of the woman performing the dance step is underexposed compared to the chromatic explosion that characterizes the predominant background on the canvas, and this serves to guide the observer to consider the meaning of the title rather than the visual focus of the gaze, that is, the dancer. In Dawn, the word is left to nature, to an unspoiled landscape of rolling hills and valleys dominated by the intense green of the meadows and grass in springtime, when everything is ready to be reborn after the cold of winter. the dawn may be the most literal one of the rising sun, but also the symbolic one of a new awareness, of an inner rebirth that cannot fail to feel welcomed by such a serene and relaxing landscape.

In the background, the lights of small towns represent a civilization that exists but is distant from the individual, as if Stefania Del Papa wanted to suggest that only after a journey of self-discovery and exploration can one approach, armed with one’s own strength, a community that too often tends to standardize and stifle individuality. Flowering is one of her most intimate works, where Realism blends with Expressionism, giving rise to an intangibility linked to the soul, to a feeling that Stefania Del Papa listens to, understands, and then conveys on canvas, as if the protagonist were asking her to go beyond the superficial patina, as if hers were a silent expectation of being truly seen. The meaning of the title, flowering, once again appears symbolic of the real meaning of the portrait because, beyond the flowers with which the author adorns the girl’s hair, what strikes is her fresh gaze, unaware of her beauty and perhaps even uncertain in the knowledge that she must embark on a complex path of growth, as if simple flowering needed a substance made up of experiences, falls, mistakes, but also the ability to overcome them. Stefania Del Papa‘s narration shows an almost maternal empathy, seeming to want to reassure the young woman and at the same time encourage her never to stop at the pursuit of appearance alone, but to cultivate that substance that will remain even when, in the inevitable course of life, she will fade and lose the beauty that now belongs to her. Stefania Del Papa discovered her artistic soul as a child and attended drawing and painting courses in both New York and Rome, such as the Scuola San Giacomo di Arti Ornamentali, and has participated in group exhibitions throughout Italy.