Molto spesso gli artisti contemporanei tendono a essere concentrati sul presente, su tutte le criticità o le riflessioni su un’attualità che da un lato costituisce un modo inedito, rispetto al passato, di affrontare l’esistenza ma dall’altro spesso tende a isolare l’individuo e a maggior ragione l’artista che sente il bisogno di oltrepassare attraverso la sua creatività quei disagi o semplicemente le osservazioni sull’attualità che diventano la base della sua produzione. Ma ve ne sono altri che invece mostrano la necessità di ripercorrere dei periodi del passato nei quali si sentono vicini, per l’entusiasmo di alcune fasi storiche, per lo charme e l’eleganza che costituivano una sorta di rispetto nei confronti di se stessi e degli altri, e in qualche modo per la nostalgia che uno stile di vita ormai quasi scomparso suscita solleticando la loro creatività e poi affascinando l’osservatore. La protagonista di oggi incentra tutta la sua produzione pittorica verso una fase storica di benessere e di rinascita europea dopo le brutalità del primo conflitto mondiale, raccontando proprio lo spirito di quegli anni ruggenti.

Gli inizi del Ventesimo secolo furono caratterizzati da un approccio all’arte completamente diverso rispetto a quello tradizionale, più sperimentatore e tendente a studiare nuove modalità, nuove intenzioni espressive e tecniche esecutive che condussero alla nascita di movimenti pittorici, che poi si ampliarono anche alla scultura, in grado di stravolgere le regole precedenti, di tracciare inediti percorsi destinati prima o poi a incontrarsi e fondersi per permettere una nuova, ulteriore evoluzione. La scomposizione dell’immagine e la sua geometrizzazione portarono verso il Futurismo e il Cubismo, quando la tecnica restava legata alla figurazione, e al Neoplasticismo e all’Astrattismo Geometrico quando invece il distacco dalla realtà osservata doveva essere radicale. I primi due movimenti si proposero, sebbene con intenzioni differenti, di costruire attraverso la divisione in figure geometriche un’immagine diversa, nel Futurismo per riprodurre il senso della velocità, dell’ottimismo per la ripresa dopo il periodo bellico e per la fiducia nei confronti delle innovazioni tecnologiche che si stavano concretizzando, mentre nel Cubismo per osservare la realtà contemporaneamente da tutti i punti di vista, in entrambi casi annullando il senso della prospettiva come accademicamente inteso, appiattendo l’immagine e utilizzando gamme cromatiche irreali quanto funzionali allo studio che i rappresentati di entrambe le correnti volevano svolgere. Nello stesso periodo però nacque una corrente pittorica più ancora legata alla bellezza, all’armonia, dove la geometricità, seppur mai rifiutata, sembrava essere appena accennata, limitata al rigore dei palazzi, dei grattacieli e del design di cui ha lasciato importanti segni negli Stati Uniti e in Europa; il nome del nuovo stile artistico era Art Déco ed ebbe tra i suoi maggiori rappresentanti una delle poche grandi artiste donne dell’epoca, Tamara De Lempicka che fu in grado di legare indissolubilmente a sé, al suo essere anticonvenzionale e coraggiosa, il movimento stesso. Le sue donne eleganti, le sue atmosfere patinate, la precisione del tratto, i colori pieni e saturi e quell’accenno di geometricità ammorbidita dalla forma tonda, sono i suoi elementi peculiari, molti dei quali si possono ritrovare in una grande artista contemporanea che ha scelto proprio l’Art Déco come tratto distintivo della sua pittura.

Catherine Abel, australiana, di formazione autodidatta e solo successivamente a una sua permanenza di tre anni a Parigi consacratasi come artista professionale affermata, riattualizza le linee guida dello stile originario arricchendole di contaminazioni futuriste e cubiste, in particolar modo negli sfondi che circondano i suoi protagonisti, quasi come se volesse sottolineare l’importanza che negli anni Venti, quelli che continuano a vivere nelle sue opere, ricoprivano il progresso, le innovazioni tecnologiche, i mezzi di trasporto, i grattacieli, spesso attori secondari delle sue affascinanti e patinate tele.

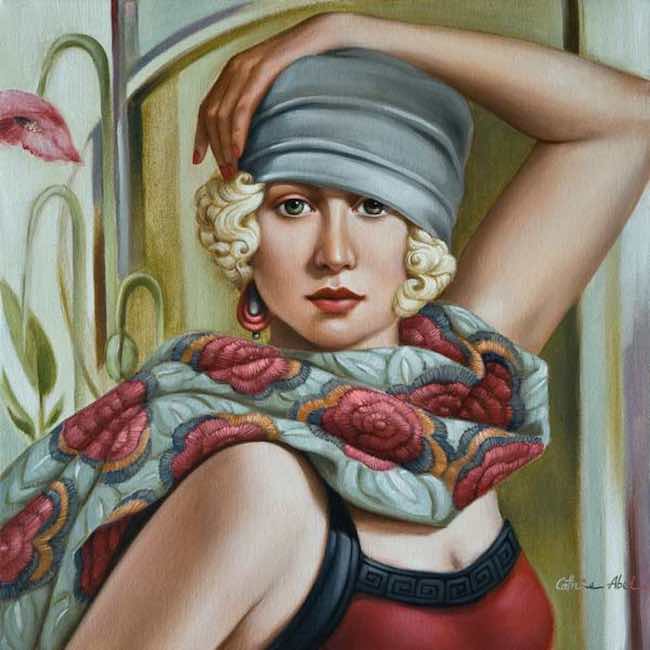

Poi però, il ruolo principale viene affidato prevalentemente alle donne, ammalianti, languide, impeccabili nel loro aspetto perché a quei tempi non era concesso di non apparire al meglio, di uscire di casa senza essere perfetti nell’aspetto esteriore perché quest’ultimo era simbolo di benessere, della ritrovata gioia di vivere dopo il periodo buio della guerra, e del desiderio di godere appieno della bellezza e del bel vivere.

I volti sono fascinosamente algidi, a volte persino snob, come se le sue protagoniste osservassero il mondo dall’alto della loro consapevolezza, verso il basso della quotidianità; in altri casi invece appaiono serene, sicure del proprio fascino e certe che prima o poi sopraggiungerà quell’elemento improvviso in grado di cambiare la loro esistenza, quasi come se il viaggio e le città fossero mondi da scoprire e da conquistare con la positività e l’autodeterminazione che fuoriesce dalle pose leziose accompagnati da un uso della luce che conduce la memoria verso la pittura rinascimentale. Ciò che però rende incredibilmente glamour le opere di Catherine Abel è l’essere sospese e testimoni della modernità simbolo di quegli anni Venti che traspare dagli edifici, dai palazzi accostati gli uni agli altri, sovrastati da dirigibili, da aerei, o circondati da navi e auto di lusso come se l’esistenza dei suoi personaggi fosse un lungo sogno di ricchezza e di benessere, il desiderio di migliorare la propria vita per approfittare di ogni istante.

Nell’opera Hamburg i due protagonisti, una coppia dell’alta società, sembra ricordare i viaggi compiuti insieme, le città visitate e i mari solcati ed è proprio la presenza dei mezzi di trasporto, elemento comune in molte delle tele della Abel, a raccontare la gioia più grande, quella passione comune che ha contraddistinto la loro vita insieme e che probabilmente ha contribuito a cementare la loro unione, la complicità che sembrano ripercorrere episodio dopo episodio. La tela appare di fatto come una macchina del tempo, come un film di tutto ciò che è stato vissuto e che appartiene indissolubilmente alla memoria; ed è proprio per questo forse che l’artista sceglie una leggera impronta futurista per descrivere lo sfondo, perché il senso del movimento dato dalla geometricità, dai raggi di luce che sembrano illuminare il ricordo, infondono ancor più nell’osservatore la sensazione di trovarsi di fronte a un fotogramma di esperienze che scorrono davanti ai suoi occhi.

L’opera Summer girl presenta caratteristiche comuni alla precedente opera, malgrado in questo caso la situazione vissuta dalla ragazza protagonista appartenga al momento presente, a un frangente di leggerezza, di speranza verso il futuro, di piacevolezza per ciò che sta osservando come se proprio lì, oltre il limite della tela, si nascondesse una pagina nuova. L’aspettativa traspare dallo sguardo un po’ malizioso e un po’ curioso della ragazza, come se i suoi pensieri corressero verso le possibilità che la città dietro di sé le offrirà, certa di essere destinata a prenderle al volo per avere il meglio. Gli abiti, la cloche, il foulard sono tipici elementi di quegli anni lontani che chiedevano la massima accuratezza nell’abbigliamento e nell’acconciatura, e che caratterizzavano una società che voleva recuperare il gusto e la bellezza come simbolo della ripresa e della nuova affermazione economica e sociale.

Il movimento, gli spostamenti, sono temi dominanti di Catherine Abel, perché erano proprio i viaggi l’occasione per incontrare, conoscere, frequentare salotti culturali, aprire la mente e, perché no?, mostrare il proprio benessere economico che costituiva uno dei presupposti per godersi tutto ciò che la vita poteva offrire; le tele Gare de l’Est e Spirit of transport rappresentano esattamente quel rinnovato entusiasmo nei confronti delle possibilità offerte dal progresso tecnologico, quella spinta a oltrepassare i confini del conosciuto e andare verso una piacevole avventura costituita da tutto ciò che poteva essere scoperto in virtù della facilità di muoversi. Le due donne sembrano essere modelle e simboli di quel modo di vivere, come se fossero state prese per promuovere i treni e le stazioni, esattamente come nelle pubblicità contemporanee dove ogni prodotto sembra necessitare avere un’affascinante testimonial. Catherine Abel ha al suo attivo mostre personali negli Stati Uniti, in Francia e ovviamente in Australia, vanta collezionisti in tutto il mondo ed è stata finalista all’Archibald Prize, al Sir John Sulman Prize e al Portia Geach Memorial Award.

CATHERINE ABEL-CONTATTI

Email: catherineabelstore@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.catherineabelstore.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/catherineabel100

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/catherineabelart/

Between Art Deco and Futurism with Catherine Abel’s sophisticated and bewitching settings

Very often contemporary artists tend to be focused on the present, on all the critical issues or reflections on a topicality that on the one hand constitutes an unprecedented way, compared to the past, of dealing with existence but on the other hand often tends to isolate the individual and all the more so the artist who feels the need to go beyond through his creativity those discomforts or simply observations on current affairs that become the basis of his production. But there are others who, on the other hand, show the need to retrace periods of the past in which they feel close, for the enthusiasm of certain historical phases, for the charm and elegance that constituted a sort of respect towards themselves and others, and in some way for the nostalgia that a lifestyle that has now almost disappeared arouses, tickling their creativity and then fascinating the observer. Today’s protagonist focuses all her pictorial production on a historical phase of European prosperity and rebirth after the brutalities of the First World War, recounting precisely the spirit of those roaring years.

The beginning of the 20th century was characterised by a completely different approach to art compared to the traditional one, more experimental and tending to study new modalities, new expressive intentions and executive techniques that led to the birth of pictorial movements, which later expanded to sculpture as well, capable of disrupting the previous rules, of tracing new paths destined sooner or later to meet and merge to allow a new, further evolution. The decomposition of the image and its geometricisation led towards Futurism and Cubism, when the technique remained linked to figuration, and to Neoplasticism and Geometric Abstractionism when the detachment from observed reality was to be radical. The first two movements set out, albeit with different intentions, to construct a different image through the division into geometric figures, in Futurism to reproduce the sense of speed, optimism for recovery after the war period and confidence in the technological innovations that were taking shape, while in Cubism to observe reality simultaneously from all points of view, in both cases cancelling the sense of perspective as academically intended, flattening the image and using unreal colour ranges as functional as they were to the study that the representatives of both currents wanted to carry out.

At the same time, however, a pictorial current was born that was more closely linked to beauty, to harmony, where geometricity, although never rejected, seemed to be barely hinted at, limited to the rigour of buildings, skyscrapers and design, of which it left important marks in the United States and Europe; the name of the new artistic style was Art Deco and it had among its greatest representatives one of the few great female artists of the time, Tamara De Lempicka, who was able to bind the movement itself inextricably to herself, to her being unconventional and courageous. Her elegant women, her glossy atmospheres, the precision of her strokes, the full, saturated colours and that hint of geometricity softened by the round shape, are her distinctive elements, many of which can be found in a great contemporary artist who has chosen Art Deco as the hallmark of her painting. Catherine Abel, an Australian, self-taught and only after a three-year stay in Paris did she become an established professional artist, updates the guidelines of the original style, enriching them with futurist and cubist contaminations, particularly in the backgrounds surrounding her protagonists, almost as if she wanted to emphasise the importance of progress, technological innovations, means of transport and skyscrapers, which were often secondary actors in her fascinating and glossy canvases, in the 1920s, the years that continue to live on in her paintings.

Then, however, the main role is entrusted mainly to women, bewitching, languid, impeccable in their appearance because in those days it was not permitted not to look one’s best, to leave the house without being perfect in one’s outward appearance because the latter was a symbol of well-being, of the rediscovered joy of living after the dark period of the war, and of the desire to enjoy beauty and the good life. The faces are charmingly algid, sometimes even snobbish, as if her protagonists were observing the world from the height of their consciousness, downwards from everyday life; in other cases, however, they appear serene, confident in their own charm and certain that sooner or later that sudden element will come along that will change their existence, almost as if the journey and the cities were worlds to be discovered and conquered with the positivity and self-determination that emanates from the leering poses accompanied by a use of light that leads the memory back to Renaissance painting. However, what makes Catherine Abel’s works incredibly glamorous is that they are suspended and bear witness to the modernity symbolic of the 1920s that transpires from the buildings, from the palaces juxtaposed one against the other, overlooked by airships, aeroplanes, or surrounded by ships and luxury cars as if the existence of her characters were one long dream of wealth and well-being, the desire to improve one’s life in order to take advantage of every moment. In the painting Hamburg, the two protagonists, a high society couple, seem to recall the journeys they have made together, the cities they have visited and the seas they have sailed, and it is precisely the presence of means of transport, a common element in many of Abel’s canvases, that recounts the greatest joy, that common passion that has marked their life together and that probably helped cement their union, the complicity that they seem to recount episode after episode.

In fact, the canvas appears like a time machine, like a film of everything that has been experienced and that belongs indissolubly to memory; and it is perhaps for this reason that the artist chooses a slight futurist imprint to describe the background, because the sense of movement given by the geometricity, by the rays of light that seem to illuminate the memory, instil even more in the observer the sensation of being in front of a photogram of experiences that flow before his eyes. The artwork Summer girl has characteristics in common with the previous painting, although in this case the situation experienced by the girl protagonist belongs to the present moment, to a juncture of lightness, of hope for the future, of enjoyment for what she is observing as if right there, beyond the edge of the canvas, a new page were hiding. Expectation shines through in the girl’s slightly mischievous, slightly curious gaze, as if her thoughts are racing towards the possibilities that the city behind her will offer, certain that she is destined to take them at face value. The clothes, the cloche, the headscarf are typical elements of those distant years that demanded the utmost care in clothing and hairstyle, and characterised a society that wanted to recover taste and beauty as a symbol of recovery and new economic and social affirmation. Movement, travel, are dominant themes in Catherine Abel’s work, because travel was the occasion to meet, to get to know, to frequent cultural salons, to open one’s mind and, why not, to show off one’s economic well-being, which was one of the prerequisites for enjoying all that life could offer; the paintings La Gare de l’Est and Spirit of transport represent exactly that renewed enthusiasm towards the possibilities offered by technological progress, that drive to go beyond the boundaries of the known and to go towards a pleasant adventure consisting of all that could be discovered by virtue of the ease of moving. The two women seem to be models and symbols of that way of life, as if they were taken to promote trains and stations, just as in contemporary advertisements where every product seems to need a charming testimonial. Catherine Abel has solo exhibitions in the United States, France and of course Australia to her credit, has collectors all over the world and has been a finalist for the Archibald Prize, the Sir John Sulman Prize and the Portia Geach Memorial Award.