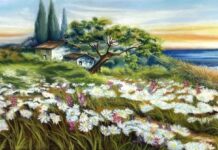

A volte lo sguardo ha bisogno di vagare e di perdersi in tutto ciò che si trova intorno ma lontano dal caos cittadino, per riuscire a ritrovarsi all’interno di una dimensione più intimista, incantata quasi proprio perché a osservare sono le corde dell’anima, quelle profondità che tendono a rimanere nascoste nel pragmatismo della quotidianità ma che invece si liberano davanti a un mondo naturale e incontaminato che avvolge l’essere umano non appena decide di allontanarsi dalla giungla urbana. Raccontare l’interazione con l’individuo attraverso la rappresentazione di una natura in cui tutto, dai colori alle atmosfere, si armonizza con il percorso percettivo e mnemonico, è la caratteristica distintiva della produzione artistica della protagonista di oggi che sceglie un mezzo espressivo incredibilmente delicato.

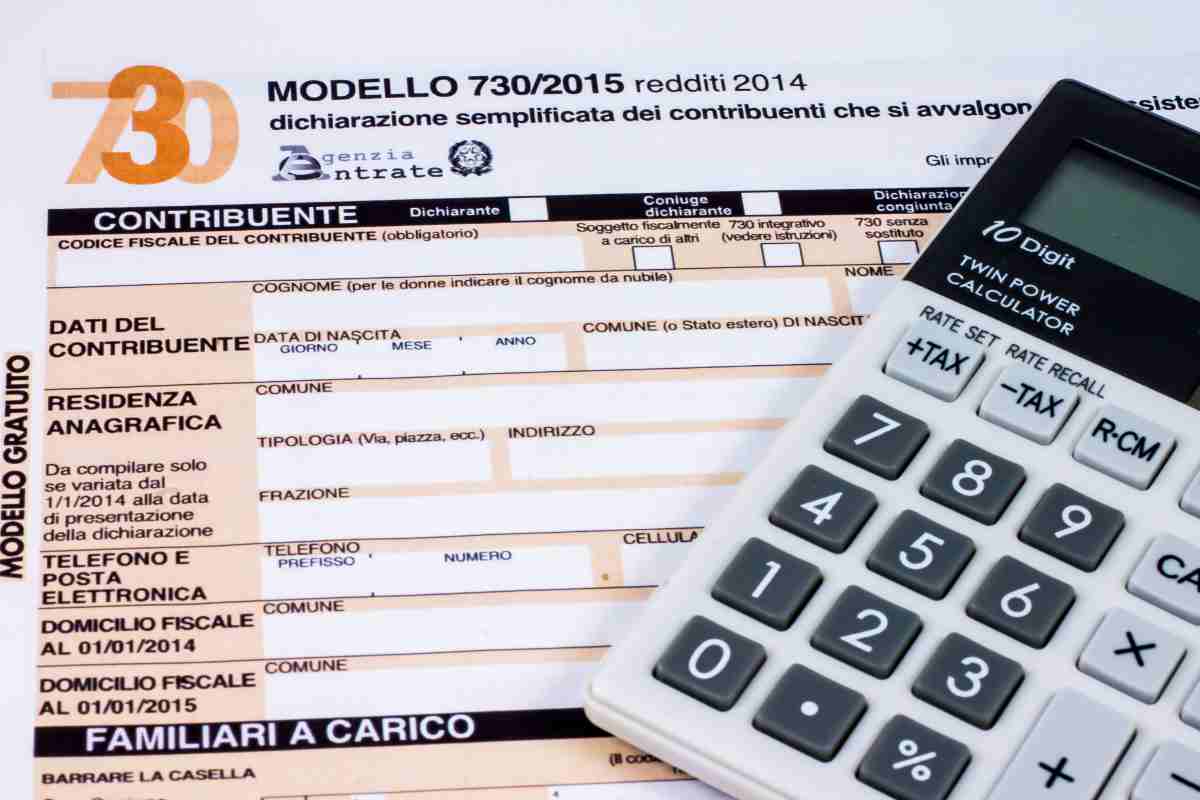

L’utilizzo del pastello cominciò ad affiancarsi al più tradizionale colore a olio nel Settecento grazie alla pittrice veneziana Rosalba Carriera, pioniera dunque non solo in qualità di donna artista in un periodo in cui l’espressione creativa era tradizionalmente legata agli uomini, che ne sfruttò la caratteristica di rendere più rarefatti e tenui i contorni dei personaggi che ritraeva, rivelando quanto il pastello riuscisse a riprodurre in maniera perfetta la delicatezza degli incarnati. Malgrado nei primi decenni dell’Ottocento la tecnica fu accantonata, con l’Impressionismo trovò nuova vita perché le atmosfere luminose e sfumate venivano realizzate grazie all’utilizzo del pastello mescolato all’olio che sulla tela si traducevano in paesaggi intensi e avvolgenti. Furono in particolar modo Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir e l’italiano Giovanni Boldini gli impressionisti che più di tutti si avvalsero dei pastelli per realizzare le loro opere, i ritratti della nobiltà i cui volti erano riprodotti in maniera fedele e armonica, le morbide ballerine che calcavano i palcoscenici, i momenti di svago della borghesia, mostrando la modernità del loro approccio pittorico anche attraverso la mescolanza di tecniche realizzative. Quasi parallelamente all’Impressionismo, trovò spazio sempre in Francia un altro movimento che intendeva esplorare tutto ciò che non era visibile agli occhi, quelle energie che scorrono al di sotto del velo della superficie collegandosi all’interiorità e mettendo così al centro della ricerca pittorica un punto di vista soggettivo piuttosto che puramente oggettivo; il Simbolismo, questo il nome del movimento emergente, richiedeva un approccio raffinato, colto, proprio perché dovevano essere comprese le metafore, le allegorie più o meno celate che gli autori inserivano nelle loro tele, ed evidenziate le ambientazioni oniriche e dunque impalpabili.

Tra i maggiori esponenti della corrente vi fu Odilon Redon che riusciva a nascondere perfettamente l’enigma, il mistero ed entità inquietanti dentro atmosfere dolci, delicate, piene di ombreggiature e di tonalità intermedie che venivano realizzate, ancora una volta, in virtù dell’utilizzo dei pastelli, mezzo prediletto per entrare in quell’universo parallelo di cui le sue tele raccontano. Anche l’autore simbolista ungherese Josef Rippl-Ronai si avvalse a sua volta della tecnica pastellista per realizzare opere in cui la suggestione, il sentire interiore, l’interpretazione, erano predominanti rispetto alla narrazione oggettiva; in lui i bastoncini di pigmento erano essenziali per riprodurre le scene a metà tra sogno e realtà o per descrivere in modo morbido e luminoso alcuni dettagli dei volti dei personaggi che ritraeva, accarezzati letteralmente dalle luci e dalle ombre che l’autore infondeva nelle sue tele. L’artista romana Claudia De Benedittis si avvicina al Simbolismo attraverso la tecnica del pastello a secco soft proprio perché la sua creatività ha bisogno di quell’atmosfera meditativa, rarefatta attraverso cui sussurrare i propri pensieri, le emozioni che si possono liberare solo quando l’anima si connette con l’intorno, con quel mondo naturale fatto di panorami incontaminati ma anche di animali che divengono metafora di una sensazione, di una percezione, ed emanazione dell’interiorità dell’autrice.

Dopo un percorso di sperimentazione e di formazione, Claudia De Benedittis non riesce più ad abbandonare il pastello, la cui tecnica ha approfondito con il maestro Rubén Belloso Adorna, al punto di diventare membro dell’Associazione Pastellisti Italiani; al contempo sviluppa un Simbolismo fondamentale per permetterle di manifestare la sua essenza creativa che non può staccarsi dall’approccio soggettivo alla realtà osservata, non riesce a non pervadere tutto ciò che si svela al suo sguardo di una capacità interpretativa carezzevole, soffice, che regala all’osservatore una dimensione parallela in cui perdersi per sentire con la stessa intensità dell’autrice.

Il suo Simbolismo pertanto perde l’accezione più misteriosa, persino inquietante che aveva contraddistinto gli autori dell’Ottocento per spostarsi verso una caratteristica più intimista, riflessiva, meditativa ma anche sensibile ai sottili messaggi colti dall’anima che si trasformano in voce narrativa tramite i pastelli. La gamma cromatica è lunare, fortemente sfumata, quasi a sottolineare quanto tutto ciò che viene osservato con l’interiorità perda i limiti contingenti, abbandoni i dettagli per assestarsi invece al confine tra realtà e immaginazione, tra ricordo di un frammento osservato e significato profondo di quanto viene colto dagli occhi ma poi rielaborato con l’anima.

Nel lavoro Il sogno Claudia De Benedittis rappresenta un bellissimo cigno bianco che si staglia, come fosse pronto a volare, davanti all’immagine in trasparenza di una ballerina, evocando il capolavoro di Čajkovskij ma oltrepassandolo per approfondire il senso più esistenzialista, quello cioè che lega il desiderio che qualcosa si verifichi alla limitante consapevolezza di non poterlo realizzare se non attraverso il sogno. Eppure la ballerina è simbolo di determinazione, di lavoro duro e resiliente sul suo corpo affinché esso possa raggiungere quel risultato di eccellenza che le potrà consentire di volare sul palcoscenico con la stessa delicatezza e regalità del cigno. La predominanza azzurra dello sfondo racconta il mondo acquatico in cui i meravigliosi animali vivono ma anche la dimensione spirituale e interiore all’interno della quale è possibile trovare la forza e la determinazione per trasformare un desiderio in realtà.

Nell’opera Libertà l’autrice sceglie di nuovo un animale per raccontare della necessità dell’essere umano di affrancarsi da tutte le catene e le briglie da cui spesso sceglie di farsi frenare, per poter correre verso un destino diverso, incognito, certo, ma forse proprio per questo assolutamente affascinante; Claudia De Benedittis sembra suggerire che a volte è necessario lasciare la propria zona sicura per mettersi in gioco e dirigersi senza paura verso un nuovo futuro, esattamente allo stesso modo in cui il cavallo protagonista del dipinto attraversa quel paesaggio a metà tra terra e acqua dove il rosso predomina e si associa al tramonto, inteso come termine di un percorso ma anche forza di percorrere tutta la strada necessaria per trovare i nuovi se stessi.

In Il ritmo della vita invece a essere protagonista è una ballerina di flamenco, con tutta la passionalità e l’energia che contraddistingue il ballo spagnolo e che viene tradotto visivamente focalizzandosi sul fermo immagine di una delle pose più tipiche, quella del roteare il mantón de manila infondendo al movimento la forza e l’ardore del ballo, come della vita. Claudia De Benedittis osserva il centro della scena, l’intensità con cui la donna esegue i passi che conosce come se stessa e che non possono fare a meno di emanare l’amore che ella prova per una disciplina, quella della danza, che fa parte della sua essenza; tutto ciò che è intorno viene fortemente sfumato, come non fosse importante, come se l’energia della protagonista si propagasse all’esterno perdendo di consistenza perché da lì in poi deve subentrare l’empatia e la sensibilità dell’osservatore che può scegliere di lasciarsi avvolgere da quel ritmo intenso prendendolo come spunto per vivere la propria vita con passionalità oppure vederlo solo da spettatore senza lasciarsi contaminare da tutto ciò che dall’opera fuoriesce.

Armonia di colori è forse una delle opere meno simboliste di Claudia De Benedittis, da cui però si manifesta il suo forte e inscindibile legame con il mondo della flora e della fauna, quasi per lei la purezza, la spontaneità e i sentimenti buoni, escludessero l’essere umano perché spesso è quest’ultimo la causa della rottura di un equilibrio primordiale che sopravvive nelle anime più pure, meno pragmatiche e in cui l’istinto e la semplicità prevalgono su calcoli mentali, su un arrivismo contemporaneo che distacca l’uomo dal suo implicito compito di essere il custode amorevole del mondo in cui abita. Il pastello in quest’opera viene utilizzato in maniera tanto delicata e impalpabile da riprodurre con la massima perfezione la morbidezza del pelo del cane, la fiducia del suo sguardo, l’amore incondizionato verso il suo padrone, tutti valori che l’uomo ha perso e che può ritrovare solo riavvicinandosi alla natura in tutte le sue forme.

Claudia De Benedittis ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre collettive importanti, come quella nella Sala del Cenacolo presso la Camera dei Deputati, quella alla Sala del Bramante in Piazza del Popolo, quelle presso il Campidoglio e alle rassegne di Piazza di Spagna promosse dalla Art Studio Tre, e a quelle dell’Associazione Cento Pittori di Via Margutta. Nell’ottobre 2024 ha realizzato una significativa mostra personale presso lo Spazio Mimesis.

CLAUDIA DE BENEDITTIS-CONTATTI

Email: claudia.deb@alice.it

Sito web: www.claudiadeb.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/claudiadebartista

Instagram: www.instagram.com/claudiadebenedittis/

The softness of pastel blends with the magic of nature in Claudia De Benedittis’ Symbolism

Sometimes the gaze needs to wander and lose itself in everything around it, but far from the chaos of the city, in order to find itself in a more intimate, enchanted dimension, precisely because are the strings of the soul that are observing, those depths that tend to remain hidden in the pragmatism of everyday life but which are instead freed in front of a natural and uncontaminated world that envelops human beings as soon as they decide to leave the urban jungle behind. Describing the interaction with the individual through the representation of nature, in which everything, from colors to atmospheres, harmonizes with the perceptive and mnemonic journey, is the distinctive feature of the artistic production of today’s protagonist who chooses an incredibly delicate means of expression.

The use of pastels began to accompany the more traditional oil colors in the 18th century thanks to the Venetian painter Rosalba Carriera, so a pioneer not only as a female artist at a time when creative expression was traditionally linked to men, who exploited its characteristic of making the contours of the characters she portrayed more rarefied and subtle, revealing how well pastel was able to perfectly reproduce the delicacy of skin tones. Although the technique was abandoned in the early decades of the 19th century, it found new life with Impressionism, because the luminous and nuanced atmospheres were achieved through the use of pastels mixed with oil, which translated into intense and enveloping landscapes on canvas. Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and the Italian Giovanni Boldini were the Impressionists who made the most use of pastels to create their works, portraits of the nobility whose faces were reproduced faithfully and harmoniously, the soft dancers who graced the stages, and the leisure activities of the bourgeoisie, demonstrating the modernity of their pictorial approach through a mixture of techniques.

Almost parallel to Impressionism, emerged in France another movement that sought to explore everything that was not visible to the eye, those energies that flow beneath the surface, connecting to the inner self and thus placing a subjective rather than a purely objective point of view at the center of pictorial research; Symbolism, as this emerging movement was called, required a refined, cultured approach, precisely because it was necessary to understand the metaphors and allegories, some more hidden than others, that the artists incorporated into their paintings, and to highlight the dreamlike and therefore intangible settings. One of the leading exponents of the movement was Odilon Redon, who was able to perfectly conceal the enigma, mystery, and disturbing entities within sweet, delicate atmospheres, full of shading and intermediate tones that were achieved, once again, through the use of pastels, his favorite medium for entering the parallel universe depicted in his canvases. Also the Hungarian symbolist artist Josef Rippl-Ronai used the pastel technique to create artworks in which suggestion, inner feeling, and interpretation predominated over objective narration. for him, pigment sticks were essential for reproducing scenes halfway between dream and reality or for describing in a soft and luminous way certain details of the faces of the characters he portrayed, literally caressed by the lights and shadows that the artist infused into his canvases.

Roman artist Claudia De Benedittis approaches Symbolism through the technique of soft dry pastel precisely because her creativity needs that meditative, rarefied atmosphere through which to whisper her thoughts, emotions that can only be released when the soul connects with its surroundings, with that natural world made up of unspoiled landscapes but also of animals that become metaphors for a feeling, a perception, and an emanation of the artist’s inner self. After a period of experimentation and training, Claudia De Benedittis can no longer abandon pastels, a technique she has studied in depth with the master Rubén Belloso Adorna, to the point of becoming a member of the Italian Pastel Artists Association; at the same time, she developed a fundamental Symbolism that allowed her to express her creative essence, which cannot be separated from her subjective approach to observed reality. She cannot help but imbue everything that reveals itself to her gaze with a caressing, soft interpretative ability that offers the observer a parallel dimension in which to lose himself and feel with the same intensity as the author. Her symbolism therefore loses the more mysterious, even disturbing meaning that had characterized nineteenth-century authors, shifting toward a more intimate, reflective, meditative characteristic that is also sensitive to the subtle messages captured by the soul, which are transformed into a narrative voice through pastels.

The color range is lunar, strongly nuanced, as if to emphasize how everything observed with the inner self loses its contingent limits, abandoning details to settle instead on the border between reality and imagination, between the memory of an observed fragment and the profound meaning of what is captured by the eyes but then reworked by the soul. In the artwork Il sogno (The Dream), Claudia De Benedittis depicts a beautiful white swan standing out, as if ready to fly, in front of the transparent image of a ballerina, evoking Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece but going beyond it to explore a more existentialist meaning, namely that which links the desire for something to happen to the limiting awareness that it cannot be achieved except through dreams. Yet the ballerina is a symbol of determination, of hard work and resilience on her body so that it can achieve that excellence that will allow her to fly on stage with the same delicacy and regality as the swan. The predominantly blue background depicts the aquatic world in which these wonderful animals live, but also the spiritual and inner dimension within which it is possible to find the strength and determination to turn a desire into reality. In the work Libertà (Freedom), the author once again chooses an animal to convey the human need to break free from all the chains and restraints that often hold back, in order to run towards a different destiny, unknown, certainly, but perhaps precisely for this reason absolutely fascinating.

Claudia De Benedittis seems to suggest that sometimes it is necessary to leave one’s comfort zone to put oneself out there and fearlessly head towards a new future, in exactly the same way that the horse in the painting crosses that landscape halfway between land and water where red predominates and is associated with sunset, understood as the end of a journey but also the strength to travel the entire road necessary to find a new self. In Il ritmo della vita (The Rhythm of Life), on the other hand, the protagonist is a flamenco dancer, with all the passion and energy that characterizes Spanish dance and which is visually translated by focusing on a freeze frame of one of the most typical poses, that of twirling the mantón de manila, infusing the movement with the strength and passion of dance, as in life. Claudia De Benedittis observes the center of the scene, the intensity with which the woman performs the steps she knows as herself and which cannot help but emanate the love she feels for a discipline, that of dance, which is part of her essence; everything around her is strongly blurred, as if it were not important, as if the protagonist’s energy were spreading outwards, losing consistency, because from then on, the empathy and sensitivity of the observer must take over. The observer can choose to let himself be enveloped by that intense rhythm, taking it as a cue to live his own life with passion, or to watch it only as a spectator without letting be contaminated by everything that comes out of the work.

Armonia di colori (Harmony of Colors) is perhaps one of Claudia De Benedittis‘ less symbolist artworks, but it nevertheless reveals her strong and inseparable bond with the world of flora and fauna, as if for her, purity, spontaneity, and good feelings exclude human beings, because it is often the latter who is the cause of the breakdown of a primordial balance that survives in the purest, least pragmatic souls and in which instinct and simplicity prevail over mental calculations, over a contemporary careerism that detaches man from his implicit task of being the loving guardian of the world in which he lives. The pastel in this work is used in such a delicate and intangible way that it perfectly reproduces the softness of the dog’s fur, the trust in its gaze, and its unconditional love for its owner, all values that man has lost and can only rediscover by reconnecting with nature in all its forms. Claudia De Benedittis has participated in important group exhibitions, such as the one in the Sala del Cenacolo at the Chamber of Deputies, the one in the Sala del Bramante in Piazza del Popolo, those at the Campidoglio and the exhibitions in Piazza di Spagna promoted by Art Studio Tre, and those of the Associazione Cento Pittori di Via Margutta. In October 2024, she held a significant solo exhibition at Spazio Mimesis.