Molti movimenti pittorici del passato sono stati sostituiti nella contemporaneità da una libertà interpretativa che contraddistingue gli artisti di oggi, i quali non hanno più delle linee guida da seguire e in cui rientrare per poter essere inseriti e identificati all’interno di una specifica corrente bensì devono relazionarsi solo e unicamente con il proprio sentire, con l’indole creativa che li conduce spesso a mettere in sinergia stili differenti eppure armonizzabili. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi fonde la sua capacità figurativa a un’interpretazione aperta e solare del mondo che lo circonda di cui studia e osserva i dettagli che poi imprime sulla tela con una tecnica innovativa che attinge però al passato.

Intorno alla fine dell’Ottocento si iniziarono a sentire, nel mondo dell’arte, i primi venti di innovazione, quell’irresistibile tendenza ad andare oltre, e a volte contro, le regole imposte dalla formazione accademica per trovare nuovi linguaggi che potessero permettere agli artisti di sentirsi più liberi, di rivoluzionare un approccio ormai non più al passo con i tempi moderni che si andavano delineando. Con le intuizioni dei Fauves la realtà osservata fu stravolta nella gamma cromatica, nelle forme e nel modo di stendere il colore, in alcuni casi persino steso sotto forma di linee come nelle opere del precursore postimpressionista Vincent Van Gogh sebbene egli fosse ancora fortemente legato al disegno, punto di partenza di ogni tela; ma fu già con l’Impressionismo che tutte le resistenze decaddero poiché se è vero che i maestri di questo stile mantennero come riferimento l’estetica e il desiderio di raccontare nella maniera più reale possibile le sensazioni provate davanti a panorami e scorci che catturavano la loro attenzione, lo è anche che il rifiuto del disegno e la frammentazione della pennellata aprirono le porte a un mondo nuovo, quello dell’interazione dei colori pieni e non più diluiti e mescolati, e della suddivisione delle immagini in piccoli tocchi del pennello attraverso i quali veniva composta l’immagine finale. Dunque i paesaggi struggenti di Claude Monet e di Auguste Renoir fecero da precursori di quella che poco più avanti, intorno agli inizi del Novecento, costituì una delle principali rivoluzioni nell’approcciare la tela; il Divisionismo, il Puntinismo, il Cubismo e infine l’Astrattismo Geometrico nacquero tutte da quell’intuizione di frammentazione che fu l’inizio dell’era artistica moderna. Non solo, lo studio compiuto da Georges Seurat, maestro del Puntinismo, svelò quanto l’accostamento di piccoli tocchi isolati di colori puri potesse dar vita, allontanandosi dall’opera, a una visione d’insieme che comprendeva sfumature e gradazioni cromatiche che si univano allontanandosi secondo il principio della ricomposizione retinica; fu proprio su questo fondamento che molti anni dopo gli studiosi si sono basati per dar vita ai pixel di cui sono composte le immagini degli schermi di computer, display, stampanti, scanner, schermi televisivi e dei contemporanei cellulari, di fatto evoluzione delle intuizioni dei maestri dei primi del Novecento. La frammentazione e la suddivisione delle pennellate sono gli spunti da cui è partito uno dei più noti impressionisti contemporanei, Leonid Afremov, recentemente scomparso, che con le sue variopinte e poetiche immagini ha affascinato il mondo dell’arte dando vita a un modo nuovo di intendere l’Impressionismo, con l’introduzione di tocchi di colore più grandi e più densi con cui movimenta i vibranti paesaggi che racconta. E da cui parte anche l’artista siciliano Salvo Distefano che sceglie la tecnica della spatola per intensificare, rendere più consistente e più grande la suddivisione dei colori, come se la sua creatività avesse bisogno di maggiore spessore per poter sfaccettare i vari aspetti della realtà osservata, i paesaggi, le persone, gli animali che solleticano la sua necessità di interpretare ed esprimere ciò da cui il suo sguardo viene colpito.

La gamma cromatica è affine alle sensazioni che sceglie di narrare, perché in fondo la pittura non è altro che descrizione dell’osservato attraverso l’armonia del colore, dunque in qualche modo introducendo un certo aspetto espressionista da questo punto di vista; nel momento in cui interpreta o si perde nella bellezza di un paesaggio le tonalità sono più tenui, quasi pastello perché legate al mondo della poesia, poi però si fanno più intense e intimiste quando descrivere il frangente di una riflessione, un attimo in cui l’individuo si perde dentro un ricordo, rimpiangendo ciò che non si ha più ma che in fondo ha permesso esattamente il percorso di approfondimento compiuto.

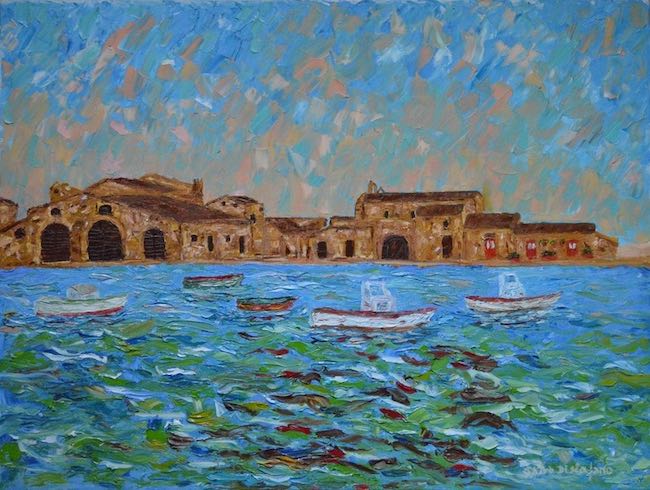

E infine ci sono le atmosfere più luminose e solari, dove l’Impressionismo lascia spazio al Realismo, nelle opere in cui Distefano si sofferma sulla bellezza dei paesaggi dell’isola in cui vive, il cielo limpido, i colori vivaci che trasformano le sue tele in vere e proprie cartoline emozionali da cui emerge l’atmosfera spensierata che avvolge la Sicilia, con le sue case in pietra, con i suoi carretti, i mandarini e con i simboli di un tempo che a volte sembra fermarsi.

Alla serie più vicina all’Impressionismo appartiene l’opera Don Chisciotte il visionario, che Salvo Distefano ritrae nella sua veste illusoria, quella dell’impavido cavaliere di ventura che si considera in grado di conquistare la Corona di Trebisonda, mentre monta il suo purosangue Ronzinante e senza riuscire più a vedere la sua vera immagine, quella del nobiluomo annoiato che cavalca un semplice ronzino e che l’artista mette sapientemente al centro della tela in nero, come a ricordare all’osservatore di quanto tutto sia frutto della fantasia del personaggio. Le spatolate sono dense, più chiare nella parte sinistra della tela, e più scure nella parte destra, perché nella seconda si nasconde forse la realtà mentre nella prima viene assecondata l’immaginazione che ha reso famoso il personaggio di Cervantes in tutto il mondo.

Nel dipinto Sola con la sua essenza invece, Distefano si sposta su un’emozione più reale, quella di una donna che sembra rimpiangere un frangente sfuggito a seguito del quale ha avvertito un vuoto da cui però è necessario liberarsi, recuperare la propria identità anche davanti a una solitudine che non sempre è negativa come sembra. La donna è ritratta nel momento del grido silenzioso che sarà il preludio della sua rinascita, della presa di coscienza della forza che le permetterà di restare in piedi senza vacillare più, a prescindere che qualcuno camminerà o no al suo fianco perché di fatto conquistando il proprio equilibrio non avrà più bisogno di appoggiarsi e potrà sentirsi finalmente libera di scegliere. Lo sfondo è contraddistinto dai toni dell’azzurro, il colore più affine all’intimità, alla riflessione, alla calma e alla serenità che è esattamente ciò che la donna è in procinto di conquistare malgrado la posa del corpo e quel capo reclinato stiano a indicare che ancora non ne sia consapevole.

Tanto vivace è l’atmosfera che circonda l’opera appena descritta, quanto invece più intimista, giocata sui toni della terra, della concretezza, dell’essenzialità del rapporto con se stessi, di Sola ma non in solitudine dove la protagonista appare fiera della sua essenza, a nudo perché è solo quando ci si pone davanti allo specchio del recente passato, delle scelte compiute, che si può prendere coscienza degli errori che hanno condotto alla condizione attuale, ma anche alla forza di non accettare compromessi che avrebbero snaturato la personalità.

L’opera Marzamemi in 500, pur essendo realizzata a spatola, mostra solo una leggera tendenza alla scomposizione perché ciò che deve emergere è la nostalgia di Distefano nei confronti di un’epoca, quella degli anni Settanta, in cui le persone non si erano ancora lasciate ammaliare dalle comodità, dalle tentazioni del benessere, e ogni viaggio diventava una meravigliosa avventura, fatta di cose semplici, di libertà, di estati serene e divertenti. In questo dipinto le pennellate sono più brevi, più affini a quelle dell’Impressionismo originale dell’Ottocento, e gli accostamenti cromatici sono funzionali a riprodurre la realtà con tutte le sue luci e le ombre, con i suoi colori vivaci, in particolar modo l’azzurro del cielo, il rosso della Cinquecento, il turchese delle porte e le decorazioni dei pupi siciliani sull’anfora, protagonisti corali di un’opera in cui ciò che emerge in maniera chiara è l’atmosfera della parte più autentica dell’isola, quella dell’interno, lontana dai percorsi turistici e per questo più in grado di conservare usi e costumi.

Salvo Di Stefano ha alle spalle un lungo cammino nel campo dell’arte, attività che ha affiancato alla sua professione, decisamente più razionale, proprio per mantenere viva una creatività che ha sempre avuto bisogno di esprimersi; ha all’attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive in Italia, in Romania, a Città del Messico e a Innsbruck, e le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private sia in Italia che all’estero.

SALVO DISTEFANO-CONTATTI

Email: salvodistefanoarte@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.salvodistefano.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/salvo.distefano.art

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/salvo_distefano67/

All the attraction of fragmentation in contemporary Impressionism by Salvo Distefano

Many pictorial movements of the past have been replaced in the contemporary world by an interpretative freedom that distinguishes today’s artists, who no longer have guidelines to follow and to fall into in order to be inserted and identified within a specific current, but must relate solely and exclusively to their own feeling, to their creative nature, which often leads them to combine different yet harmonisable styles. The artist I am going to tell you about today combines his figurative skills with an open and sunny interpretation of the world around him, of which he sudies and observes the details that he then imprints on the canvas with an innovative technique that nonetheless draws on the past.

Around the end of the 19th century, began to be felt in the art world the first winds of innovation, that irresistible tendency to go beyond, and sometimes against, the rules imposed by academic training in order to find new languages that could allow artists to feel freer, to revolutionise an approach that was no longer in step with the modern times that were emerging. With the intuitions of the Fauves, the reality observed was distorted in the range of colours, in the shapes and in the way colour was spread, in some cases even in the form of lines as in the paintings of the postimpressionist forerunner Vincent Van Gogh even though he was still strongly tied to drawing, the starting point of every canvas; but it was already with Impressionism that all resistance fell away, for if it is true that the masters of this style maintained as a reference point the aesthetic and the desire to recount as realistically as possible the sensations they felt in front of the panoramas and views that captured their attention, it is also true that the rejection of drawing and the fragmentation of the brushstroke opened the door to a new world, that of the interaction of full colours, no longer diluted and mixed, and of the subdivision of images into small touches of the brush through which the final image was composed. Thus, the poignant landscapes of Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir acted as precursors of what a little later, between the last years of the 19th and the first two decades of the 20th century, constituted one of the main revolutions in approaching the canvas; Divisionism, Pointillism, Cubism and finally Geometric Abstractionism were all born from that intuition of fragmentation that was the beginning of the modern artistic era. Not only that, the study carried out by Georges Seurat, the master of Pointillism, revealed how the juxtaposition of small, isolated touches of pure colours could give rise to an overall vision that included nuances and colour gradations that came together by distancing themselves according to the principle of retinal recomposition; it was precisely on this foundation that scholars many years later drew upon to create the pixels of which the images of computer screens, displays, printers, scanners, television screens and contemporary mobile phones are composed, in fact an evolution of the intuitions of the masters of the early 20th century.

The fragmentation and subdivision of brushstrokes are the starting points of one of the most famous contemporary Impressionists, Leonid Afremov, who recently passed away, and whose colourful and poetic images fascinated the art world, giving rise to a new way of intending Impressionism, with the introduction of larger and denser touches of colour with which he enlivened the vibrant landscapes he portrayed. This is also the starting point for the Sicilian artist Salvo Distefano, who chooses the spatula technique to intensify, make the subdivision of colours more consistent and larger, as if his creativity needed more depth to be able to facet the various aspects of the reality observed, the landscapes, people, animals that tickle his need to interpret and express what his gaze is struck by. The colour range is akin to the sensations he chooses to narrate, because after all, painting is nothing more than a description of the observed through the harmony of colour, thus somehow introducing a certain expressionist aspect from this point of view; when interpreting or losing oneself in the beauty of a landscape, the tones are more subdued, almost pastel because they are linked to the world of poetry, but then they become more intense and intimist when describing the juncture of a reflection, a moment in which the individual loses himself within a memory, regretting what one no longer has but which, after all, has allowed exactly the path of deepening that has been accomplished. And finally, there are the brighter, sunnier atmospheres, where Impressionism gives way to Realism, in the artowrks in which Distefano dwells on the beauty of the landscapes of the island where he lives, the clear sky, the vivid colours that transform his canvases into true emotional postcards from which emerges the carefree atmosphere that envelops Sicily, with its stone houses, carts, mandarins and the symbols of a time that sometimes seems to stand still. To the series closest to Impressionism belongs the painting Don Quixote the visionary, which Salvo Distefano portrays in his illusory guise, that of the fearless knight of fortune who considers himself capable of conquering the Crown of Trebizond, as he mounts his thoroughbred Rocinante, and without being able to see his true image, that of the bored nobleman riding a simple nag, which the artist cleverly places in the centre of the canvas in black, as if to remind the observer of how much everything is the fruit of the character’s imagination.

The brushstrokes are dense, lighter on the left-hand side of the canvas, and darker on the right-hand side, because in the latter reality is perhaps concealed while in the former the imagination that made Cervantes’ character famous throughout the world is indulged. In the painting Alone with her essence, on the other hand, Distefano shifts to a more real emotion, that of a woman who seems to regret an elapsed time following which she has felt an emptiness from which, however, it is necessary to free herself, to recover her own identity even in the face of a loneliness that is not always as bad as it seems. The woman is portrayed at the moment of the silent cry that will be the prelude to her rebirth, to the realisation of the strength that will allow her to stand without wavering any longer, regardless of whether or not someone will walk beside her, because by conquering her own equilibrium she will no longer need to lean and will finally feel free to choose. The background is marked by shades of blue, the colour most akin to intimacy, reflection, calm and serenity, which is exactly what the woman is in the process of conquering, even though the pose of her body and that bowed head indicate that she is not yet aware of it. The atmosphere surrounding the artwork just described is as lively as it is more intimist, played out in earthy tones, of concreteness, of the essential nature of the relationship with oneself, of Alone but not lonely where the protagonist appears proud of her essence, naked because it is only when one stand in front of the mirror of the recent past, of the choices made, that one can become aware of the errors that have led to the current condition, but also of the strength not to accept compromises that would have distorted the personality. The work Marzameni in 500, although made with a spatula, shows only a slight tendency to decomposition because what must emerge is Distefano‘s nostalgia for an era, that of the 1970s, when people had not yet allowed themselves to be bewitched by comfort, by the temptations of wealth, and every trip became a wonderful adventure, made up of simple things, of freedom, of serene and enjoyable summers.

In this painting, the brushstrokes are shorter, more akin to those of the original 19th century Impressionism, and the colour combinations are functional in reproducing reality with all its lights and shadows, with its vivid colours, especially the blue of the sky, the red of the Cinquecento, the turquoise of the doors and the decorations of the Sicilian puppets on the amphora, the choral protagonists of an artwork in which what clearly emerges is the atmosphere of the most authentic part of the island, that of the interior, far from the tourist routes and for this reason better able to preserve customs and traditions. Salvo Di Stefano has a long journey in the field of art behind him, an activity that he has flanked with his decidedly more rational profession, precisely to keep alive a creativity that has always needed to express itself. He has participated in many group exhibitions in Italy, Romania, Mexico City and Innsbruck, and his works are part of private collections both in Italy and abroad.