In un mondo in continuo progresso, al costante inseguimento di una perfezione tecnologica che mira a sostituire in molti ruoli l’essere umano, forse l’atteggiamento più rivoluzionario è quello di rimanere legati a tutto ciò che invece contraddistingue l’uomo con tutti i suoi difetti, le sue imperfezioni, la sua incapacità di rientrare dentro canoni ben precisi al punto di sentirsi talvolta inadeguato, ma soprattutto di lasciar emergere l’anima; questo è l’approccio che molti artisti scelgono di avere nei confronti dell’arte intesa come espressione di un’unicità e di un’emozionalità che non potrà mai essere sostituita da alcuna macchina, da alcuna intelligenza tecnologica semplicemente perché la pittura così come la scultura partono dall’interiorità dell’autore dell’opera che si concretizza sulla tela o sulla materia e poi liberano quella stessa sensazione verso l’osservatore che ne riceve le vibrazioni sulla base della propria unica soggettività. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi, attraverso uno stile fortemente figurativo, riesce a mettere in evidenza tutte quelle lievi sfaccettature ma anche le sfumature caratteriali o le emozioni legate al frangente vissuto dei suoi protagonisti.

Verso la seconda metà dell’Ottocento cominciò a delinearsi una frattura tra la rappresentazione tradizionale della realtà osservata, a cui era legato il Realismo, e la necessità di introdurre un’innovazione che permettesse alla pittura di essere al passo con i tempi moderni, più veloci proprio perché l’industrializzazione stava cominciando a introdurre innovazioni tecnologiche in grado di facilitare la quotidianità ma anche tese a sostituire in qualche modo il ruolo dell’arte intesa come raffigurazione dell’osservato. La macchina fotografica di fatto poteva rimpiazzare il ritratto realista e anche gli scorci paesaggistici pertanto l’arte doveva trovare un modo per divenire irriproducibile dalla nuova tecnologia, pur continuando a parlare un linguaggio chiaro che consentisse agli appassionati di calarsi nelle atmosfere narrate; questo fu uno dei motivi fondanti dell’Impressionismo, un movimento pittorico che si proponeva di raccontare i momenti salienti della vita della borghesia dell’epoca, con l’originalità di pennellate brevi e frammentate che nulla avevano a che vedere con la definizione e perfezione dell’immagine del Realismo, pur andando a ricercare la fedele resa della luce e dell’interazione tra colori funzionale a infondere nell’osservatore la sensazione di trovarsi all’interno dei paesaggi o dei frangenti descritti. Il dinamismo visivo e l’intensità della frammentazione del colore rendevano i personaggi vivi e cangianti, come se ogni singolo dettaglio andasse a sottolineare la sensazione vissuta, tanto quanto nei paesaggi era funzionale a dare il senso generale dell’atmosfera. Nel corso degli anni seguenti, l’arte è evoluta, ha compiuto un distacco totale dalla rappresentazione del reale e poi è tornata verso di essa per riavvicinarsi al grande pubblico, a quella nuova classe media che dominava negli anni Sessanta del Novecento e che desiderava entrare in un mondo che per formazione culturale gli era sconosciuto; nel contempo ha osservato l’introduzione di nuovi mezzi espressivi, la Computer Art, poi divenuta Arte Digitale, l’Arte Concettuale e le Installazioni, completamente distaccate dall’osservato per tendere verso il significato più interiore. E ancora la ricerca della perfezione esecutiva con l’Iperrealismo, dove era la pittura che doveva parlare lo stesso linguaggio della fotografia di fatto superandola in perfezione ed espressività, fino a giungere al momento attuale dove la libertà rappresentativa degli artisti di poter scegliere la cifra stilistica più affine alle proprie corde deve fare i conti con un’evoluzione tecnologica che ha recentemente introdotto l’intelligenza artificiale con cui le immagini appaiono assolutamente reali. Tanto reali quanto prive di ciò che invece da sempre contraddistingue l’arte, e cioè l’anima, l’interiorità, la sensazione, l’emozione che si riflette in tutto ciò che è il prodotto di un artista. La pittrice Alina Ciuciu, di origine rumena ma ormai da anni residente in Italia, sottolinea invece l’unicità dell’arte attraverso uno stile che non può non sfuggire alla riproduzione, perché ciò che contraddistingue i suoi soggetti è quell’apparato prismatico, quel susseguirsi di sottili sfumature, frammentate, che rendono impossibile inquadrare il soggetto se non nell’ambito di quell’istante colto dalla sensibilità dell’artista e tradotto sulla tela sotto forma di emozione.

Dunque l’anima diviene protagonista, non solo del risultato dell’atto pittorico bensì anche della fase precedente, quella dell’osservazione a cui segue l’inizio della creazione poiché è in quell’esatto istante che si concretizza l’intenzione poetica dell’autrice da cui poi fuoriesce quella girandola di tonalità più o meno lievi che vanno a comporre il complesso puzzle della costruzione di un attimo irripetibile che giunge a far vibrare le corde interiori di chi quel risultato lo osserva.

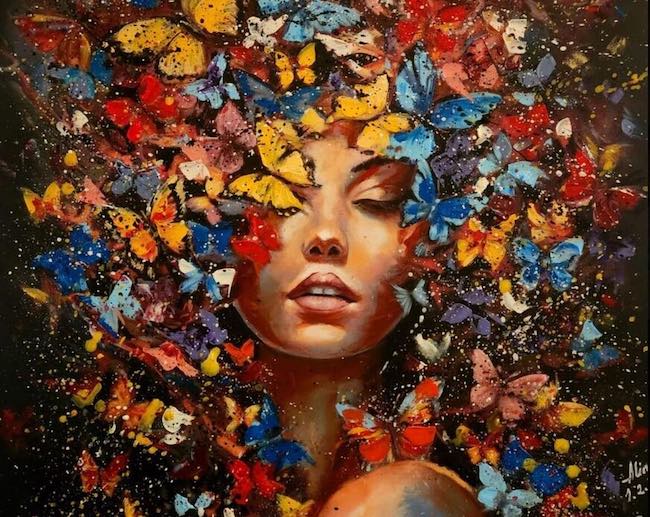

Lo stile Realista dei volti, perfettamente definiti nella carnagione, nel gioco di luci e ombre e soprattutto nella profondità degli sguardi, si trasforma in Impressionismo per tutto ciò che incornicia quei visi intensi, gli abiti e anche l’ambiente circostante, perché è attraverso la scomposizione dei colori che si amplifica il sentire, la sensazione che Alina Ciuciu descrive magistralmente esattamente in virtù di quella tendenza alla frammentazione. L’enfatizzazione del sentire diviene pertanto cornice, abbraccio nei confronti dei personaggi che si amplifica verso l’esterno giungendo diretta all’osservatore che non può non provare le stesse sensazioni di cui le tele sono immerse, dando vita così a una connessione di cui l’anima è protagonista.

L’unicità della pittura si allontana così da qualsiasi tentativo tecnologico di imitarla, proprio in virtù di queste personalizzazioni che rimbalzano dal sentimento creativo dell’artista alla tela che diviene prodotto della creazione ma anche amplificatore di emozioni e poi ancora verso il fruitore che ne assorbe l’intenzione e la poesia espressiva; l’intento creativo di Alina Ciuciu è dunque quello di mostrare quanto impossibile sia per qualsiasi riproduzione o intelligenza artificiale riuscire a raggiungere l’elevazione emozionale dell’arte tradizionalmente intesa, poiché nessuna macchina sarà mai in grado di infondere l’anima, la sensazione, la sensibilità singola e unica di ciascun autore, all’interno di un prodotto a cui mancheranno sempre la morbidezza e le sfumature che appartengono solo all’essere umano.

In Out of time (Fuori dal tempo) la donna sembra essere sospesa in un instante di attesa o forse di rammarico per la consapevolezza di aver lasciato sfuggire quell’occasione unica e irripetibile, un’istante che l’ha condotta a voltarsi indietro e a valutare quanto ormai non sia più possibile recuperare ciò che è stato perso un attimo prima; tutto intorno al volto sembra esservi un fermo immagine dove però il movimento resta presente, come se fosse una scia di ciò che è passato sotto lo sguardo e non è stato colto generando così una sorta di sorpreso rimpianto, forse non ancora giunto alla completa coscienza.

In King of our soul (Re della nostra anima), il Cristo narrato da Alina Ciuciu è incredibilmente umano, lirico nel suo dolore, dispiaciuto di non avere più il tempo per diffondere il suo messaggio di pace e amore eppure consapevole che sarà esattamente in virtù del suo sacrifico che quel messaggio gli sopravvivrà e si diffonderà tra tutti i popoli del mondo. Nella tela la gamma cromatica scelta dall’artista è affine all’aura mistica che avvolge il figlio di Dio, mette in evidenza tutta quella cupezza che egli stesso sapeva di dover attraversare prima di poter trasformare tutto in luce, e soprattutto contrappone la sua incredibile intensità all’incomprensione che ha avvolto il suo passaggio, traducendola con la forma di sfumature sfaccettate e indefinibili.

E ancora in Jealous of a flower (Geloso di un fiore) Alina Ciuciu racconta un’altra età, quella dell’infanzia, della purezza di due bambini intimiditi dalle loro stesse emozioni che si interfacciano con la spontaneità tipica dell’innocenza e dunque tutto l’ambiente circostante si fa da parte, sembra diventare solo e unicamente il palcoscenico dove si svolge la scena che ha catturato l’attenzione dell’artista nel momento in cui l’ha avuta davanti agli occhi o in cui l’ha immaginata. L’istante magico è quello in cui il bambino comprende che le attenzioni della bambina sono state distratte dalla presenza dei fiori gialli e così tenta di nasconderli mettendoli sotto i piedi perché desidera tornare a essere protagonista del suo cuore; lo sguardo di Alina Ciuciu si soffema esattamente sulla timidezza imbronciata del ragazzino che trova il coraggio di compiere un gesto che sorprende la bambina, inconsapevole del reale motivo del gesto.

Tutta la capacità percettiva di ogni artista diviene dunque la linea di demarcazione tra riproduzione e interpretazione, tra descrizione oggettiva e narrazione soggettiva di ciò che appartiene all’osservato e che attraverso lo sguardo di un creativo in generale, e di Alina Ciuciu in particolare, si trasforma in una poesia per immagini in cui l’osservatore viene inevitabilmente coinvolto. Alina Ciuciu ha alle sue spalle un importante e lungo percorso espositivo sia in Italia che all’estero e dal 15 al 27 aprile sarà protagonista di una mostra personale patrocinata dall’Ambasciata di Romania dal titolo L’Unicità del volto presso la sede dell’Accademia di Romania in Roma.

Marta Lock

ALINA CIUCIU-CONTATTI

Email: alina.ciuciu18@gmail.com

Sito web: www.artedialina.com/about.php

Linkedin: www.linkedin.com/in/alinaciuciu/

Instagram: www.instagram.com/alinaciuciu/

Alina Ciuciu’s Realist Impressionism, when the subject shows itself with all its infinitesimal and emotional facets

In a world in continuous progress, in constant pursuit of a technological perfection that aims to replace the human being in many roles, perhaps the most revolutionary attitude is to remain attached to everything that instead distinguishes man with all his flaws, his imperfections, his inability to fit within precise canons to the point of sometimes feeling inadequate, but above all to let the soul emerge; this is the approach that many artists choose to have towards art understood as the expression of a uniqueness and emotionality that can never be replaced by any machine, by any technological intelligence, simply because painting as well as sculpture start from the interiority of the author of the artwork that concretizes on canvas or material and then release that same sensation towards the observer who receives its vibrations on the basis of his own unique subjectivity. The artist I am going to tell you about today, through a strongly figurative style, succeeds in highlighting all those subtle facets, but also the character nuances or emotions linked to the lived circumstances of her protagonists.

Towards the second half of the 19th century, began to emerge a fracture between the traditional representation of observed reality, to which Realism was linked, and the need to introduce an innovation that would allow painting to keep up with modern times, which were faster precisely because industrialisation was beginning to introduce technological innovations that could facilitate everyday life, but also tended to replace in some way the role of art as a depiction of the observed. The camera could in fact replace the realistic portrait and even landscape views, so art had to find a way to become irreproducible by the new technology, while still speaking a clear language that would allow enthusiasts to immerse themselves in the narrated atmospheres; this was one of the founding motifs of Impressionism, a pictorial movement that aimed to recount the highlights of the life of the bourgeoisie of the time, with the originality of short, fragmented brushstrokes that had nothing to do with the definition and perfection of the image of Realism, while striving for the faithful rendering of light and the interaction of colours that was functional to instil in the observer the sensation of being inside the landscapes or the events described. The visual dynamism and the intensity of the fragmentation of colour made the characters come alive and iridescent, as if every single detail emphasised the feeling experienced, just as in the landscapes it was functional to give the general sense of atmosphere.

In the years that followed, art evolved, it made a total detachment from the representation of reality and then returned to it in order to get closer to the general public, to that new middle class that dominated in the 1960s and wished to enter a world that was unknown to them in terms of cultural formation; at the same time, it observed the introduction of new means of expression, Computer Art, which later became Digital Art, Conceptual Art and Installations, completely detached from the observed in order to tend towards the most interior meaning. And again the search for executive perfection with Hyperrealism, where it was painting that had to speak the same language as photography, in fact surpassing it in perfection and expressiveness, up to the present day where the representative freedom of artists to be able to choose the stylistic figure most akin to their own chords must come to terms with a technological evolution that has recently introduced artificial intelligence with which images appear absolutely real. As real as they are devoid of what has always distinguished art, namely the soul, the interiority, the sensation, the emotion that is reflected in everything that is the product of an artist.

On the other hand, the painter Alina Ciuciu, of Romanian origin but now living in Italy for many years, emphasises the uniqueness of art through a style that cannot fail to elude reproduction, because what distinguishes her subjects is that prismatic apparatus, that succession of subtle, fragmented nuances that make it impossible to frame the subject except in the context of that instant captured by the artist’s sensitivity and translated onto canvas in the form of emotion. Therefore, the soul becomes the protagonist, not only of the result of the pictorial act, but also of the previous phase, that of observation followed by the beginning of creation, since it is in that exact instant that the poetic intention of the author is realised, from which then emerges that whirlwind of more or less subtle tones that go to make up the complex puzzle of the construction of a unrepeatable moment that comes to vibrate the inner chords of those who observe that result. The Realist style of the faces, perfectly defined in the complexion, in the play of light and shadow and above all in the depth of the gazes, turns into Impressionism for everything that frames those intense faces, the clothes and also the surrounding environment, because it is through the decomposition of the colours that the feeling is amplified, the sensation that Alina Ciuciu masterfully describes precisely by virtue of that tendency towards fragmentation.

The emphasisation of feeling therefore becomes a frame, an embrace towards the characters that is amplified outwards, reaching directly to the observer who cannot help but feel the same sensations with which the canvases are immersed, thus creating a connection in which the soul is the protagonist. The uniqueness of painting thus distances itself from any technological attempt to imitate it, precisely by virtue of these personalisations that bounce back from the artist’s creative feeling to the canvas, which becomes a product of creation but also an amplifier of emotions, and then on to the observer who absorbs its intention and expressive poetry; Alina Ciuciu‘s creative intent is thus to show how impossible it is for any reproduction or artificial intelligence to succeed in achieving the emotional elevation of art as traditionally understood, since no machine will ever be able to infuse the soul, the feeling, the individual and unique sensitivity of each creator, into a product that will always lack the softness and nuances that belong only to the human being. In Out of time, the woman seems to be suspended in an instant of expectation or perhaps regret for the awareness of having let that unique and unrepeatable opportunity slip by, an instant that has led her to look back and assess how it is now no longer possible to recover what was lost a moment before; all around the face there seems to be a still image where, however, the movement remains present, as if it were a trail of what has passed under one’s gaze and has not been caught, thus generating a sort of surprised regret, perhaps not yet fully realised. In King of our soul, the Christ narrated by Alina Ciuciu is incredibly human, lyrical in his pain, regretting that he no longer has the time to spread his message of peace and love and yet aware that it will be precisely by virtue of his sacrifice that that message will survive him and spread to all the peoples of the world. In the canvas, the chromatic range chosen by the artist is akin to the mystical aura that envelops the son of God, highlighting all that gloom that he knew he had to go through before he could transform everything into light, and above all contrasting his incredible intensity with the incomprehension that enveloped his passage, translating it into the form of multifaceted and indefinable shades.

And again in Jealous of a flower, Alina Ciuciu recounts another age, that of childhood, of the purity of two children intimidated by their own emotions that interface with the spontaneity typical of innocence, and thus the whole of the surrounding environment steps aside, seeming to become solely and only the stage where the scene that captured the artist’s attention at the moment she had it in front of her eyes or imagined it takes place. The magical instant is when the child realises that the girl’s attentions have been distracted by the presence of the yellow flowers and so he tries to hide them by putting them under his feet because he wishes to be the protagonist of her heart once again; Alina Ciuciu‘s gaze lingers precisely on the sullen shyness of the little boy who finds the courage to make a gesture that surprises the little girl, unaware of the real reason for the gesture. The entire perceptive capacity of each artist thus becomes the dividing line between reproduction and interpretation, between objective description and subjective narration of what belongs to the observed and that through the gaze of a creative artist in general, and of Alina Ciuciu in particular, is transformed into a poem for images in which the observer is inevitably involved. Alina Ciuciu has behind her an important and long exhibition career both in Italy and abroad, and from 15 to 27 April she will be the protagonist of a personal exhibition sponsored by the Romanian Embassy entitled The Uniqueness of the Face at the headquarters of the Romanian Academy in Rome.