Cercare di distaccare l’essere umano dalla fretta del vivere contemporaneo è una caratteristica che appartiene all’arte visiva, poiché essa presuppone uno sforzo osservativo che vada oltre il primo impatto e scenda verso significati che spesso si nascondono al di sotto del velo più superficiale; le riflessioni indotte dai singoli interpreti della pittura e della scultura attuale sono più o meno esplicite sulla base dello stile che sentono più affine alla loro natura espressiva, ma in tutti i casi la connessione, il dialogo con l’emotività, sono essenziali per dialogare con un fruitore che ha bisogno di aprirsi in maniera empatica per cogliere il messaggio dell’esecutore di un’opera. La protagonista di oggi, attraverso un linguaggio pittorico tradizionale, sembra voler invitare l’osservatore ad allontanarsi dalla contingenza ricreando le stesse atmosfere contemplative che appartenevano ai secoli scorsi, quando il progresso non aveva allontanato l’uomo dalla sua tranquillità esistenziale e quando la lentezza era l’imperativo per poter assaporare la vita.

Intorno ai primi anni del Diciannovesimo secolo l’attenzione di alcuni artisti si distaccò dagli interni e dai ritratti dell’aristocrazia e delle famiglie reali, così come dai temi religiosi o mitologici, che erano stati prevalenti nella pittura precedente, per spostarsi verso la rappresentazione della natura come elemento protagonista di grande rilevanza. Tale punto di vista emerse in particolar modo con il Romanticismo Inglese, dove l’irruenza dei fenomeni atmosferici e dei mari in tempesta di William Turner, il quale sottolineò per primo il rapporto tra grandezza della natura ed esiguità dell’essere umano, conviveva con la nostalgia suscitata dalla pura bellezza delle campagne di John Constable. Con entrambi gli autori fu chiaro che il paesaggio non sarebbe più stato un genere secondario bensì aveva trovato spazio in un contesto artistico in chiaro fermento evolutivo che cominciava a porre maggiore attenzione all’essere umano e alle sue sensazioni più profonde, comprese dunque quelle dell’autore che si diffondevano nell’opera.

Già nel Diciottesimo secolo il genere della Natura morta aveva conquistato un proprio spazio, mostrando quanto anche qualcosa di non raffigurante la figura umana, sebbene eseguito inseguendo la perfezione estetica, portasse con sé tutta una serie nascosta di emozioni che permeava le opere svelando l’interiorità e la sensibilità degli artisti che sceglievano quei soggetti. Con il proseguire dell’Ottocento si andò affermando il Realismo che da un lato rendeva protagonisti personaggi appartenenti al popolo, lavoratori dei campi che il contatto con la natura lo vivevano quotidianamente come parte della loro routine, dall’altro costituì un’evoluzione stilistica in cui veniva mantenuta l’aderenza figurativa alla realtà, molto più di quanto fece il Romanticismo Inglese, pur scegliendo di distaccarsi dall’oggettività per entrare nella sfera dell’interpretazione, di quella possibilità per l’autore di avvolgere le tele con una morbidezza che rendeva le atmosfere soffuse e vellutate.

La sintesi perfetta di quanto appena esposto fu effettuata dalla Scuola di Barbizon che unì appunto la narrazione del paesaggio all’analisi sottile della società dell’epoca, dove molti lavoravano alacremente per far arricchire pochi; ma il loro studio della realtà non si soffermava sulla critica sociale bensì tendeva semplicemente a mettere in risalto la spontaneità e la semplicità della vita del popolo, quasi ammirandone l’impegno e lo stoicismo nell’affrontare gli forzi quotidiani. Gustave Courbet e Jean- François Millet mostratono quanto la natura non fosse più solo una comprimaria dell’essere umano, bensì una co-protagonista accogliente e fondamentale per l’esistenza quotidiana; entrambi, proprio per la loro visione sul ruolo rilevante della natura, eseguirono molte nature morte in cui emergevano le vibrazioni di quegli istanti familiari e rassicuranti che conquistavano lo sguardo dell’osservatore proprio perché riconducibili a sensazioni comuni. L’artista ungherese Eszter Gróf mostra nella sua produzione artistica un’anima incredibilmente classica e tradizionale, si riallaccia alle esperienze del Romanticismo Inglese e della Scuola di Barbizon per mettere in risalto non solo l’importanza oggettiva della natura e la sua capacità di proteggere e prendersi cura della vita, bensì anche la sua rilevanza esistenziale poiché è grazie a essa, alla sua contemplazione, che l’essere umano moderno può chiudere la porta al mondo esterno e immergersi in una dimensione ferma, immobile, dove non esiste fretta né frenesia del dover fare qualcosa.

Prendersi una pausa, tirare un sospiro di sollievo e ricordare la lenta piacevolezza di tutto ciò che esiste intorno alla quotidianità, sono considerati privilegi dall’individuo moderno, eppure Eszter Gróf con la sua immediatezza espressiva, riesce a creare dei fermo immagine che vanno a sollecitare proprio l’incofessata esigenza di ritrovare la vera essenza, quella più profonda e in grado di emergere solo e unicamente attraverso il contatto con il sé primordiale.

Le sue tele sono avvolte di emozioni, di ricordi, di riferimenti a qualcosa di osservato, di visto in un determinato frangente o in una specifica circostanza e che si va a fissare in un cassetto della memoria emotiva chiuso e relegato in un angolo nascosto; la capacità innata di Eszter Gróf è quella di farli riemergere grazie alle sue narrazioni di forte impatto visivo, perché raccontano ed esaltano la bellezza della realtà osservata, e alla sua naturale maestria nell’imprimere in quell’estetica perfetta frammenti di sentimenti che non possono fare a meno di fuoriuscire avvolgendo l’osservatore.

Lo stile realista si concretizza principalmente con l’olio su legno, ma negli ultimi tempi Eszter Gróf sta sperimentando anche la tecnica dell’acquerello che infonde un’aura lirica alle sue opere. Spostandosi con disinvoltura dalla natura morta ai paesaggi, il denominatore comune rimane pertanto l’intento concettuale di indurre il fruitore a comprendere l’importanza di un contatto, troppo spesso perduto nel vivere moderno, con quel ritmo rallentato dentro cui è possibile interrogarsi, comprendere la reale direzione che vorrebbe prendere la propria anima e mettersi in contatto con un’indole autentica soffocata dalla velocità e dall’urgenza degli obiettivi da inseguire.

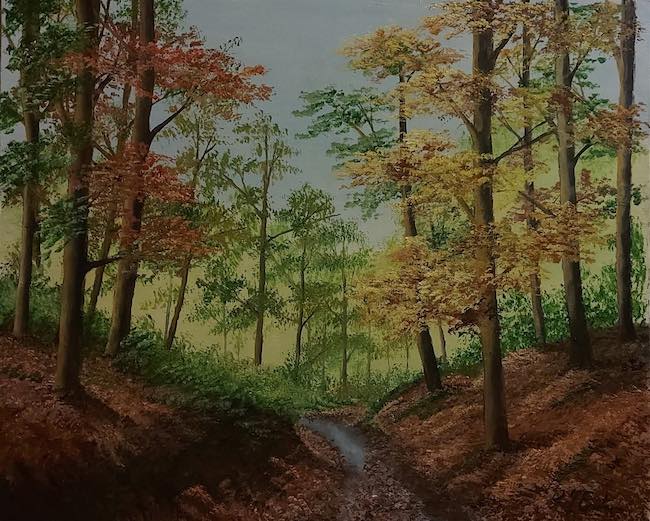

Királyrét Fishing Lake appartiene al lato più paesaggista di Eszter Gróf, e immortalando lo scorcio di un lago della sua bellissima nazione riesce a permettere di percepirne la calma, la tranquillità, il silenzio suggestivo che spinge a desiderare di entrare in quell’atmosfera poetica e solitaria, quasi l’interiorità sapesse di aver bisogno di quell’attimo di astrazione dal rumore cittadino. La luce scolpisce una parte del pontile e si riflette sull’acqua più vicina alla parte inferiore del lago mentre il resto rispecchia le chiome degli alberi che si trovano sulle due sponde; la sensazione di immobilità è sottolineata e amplificata dalla totale assenza dell’essere umano, come se qualsiasi elemento esterno andrebbe a rompere un equilibrio meraviglioso che culla lo sguardo. Ma la liricità più intensa della pittura di Eszter Gróf si rivela nelle nature morte poiché in queste opere l’autrice inserisce il ricordo, la memoria di qualcosa di familiare, un dettaglio che evoca una scena appartenente alla quotidianità e che viene lasciata in sospeso, quasi i protagonisti si fossero spostati per permetterle di immortalare quel frammento di vita da cui si lascia emozionare.

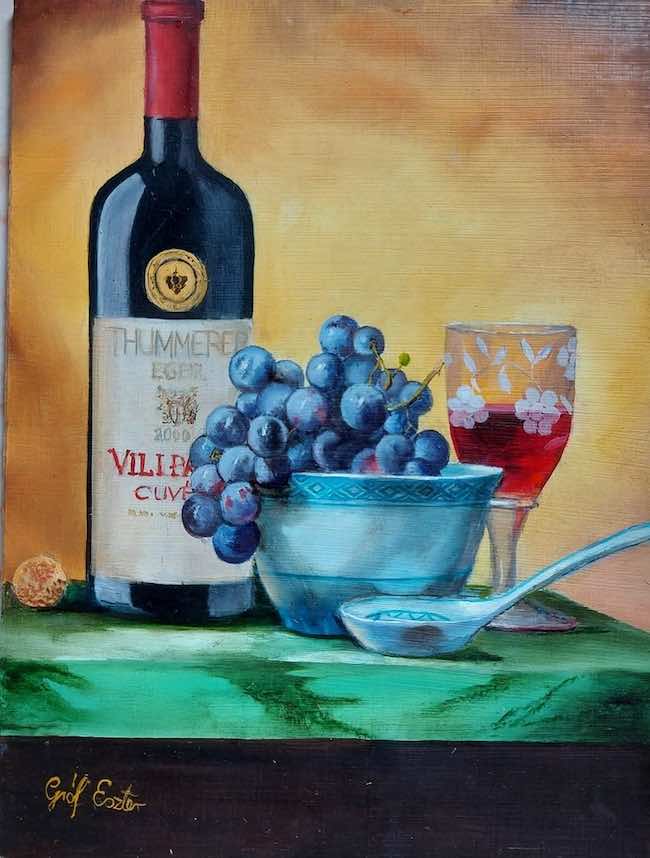

La tela Vili Papa (Papà Vili), parla esattamente di questo, mette in evidenza un’abitudine, riunisce gli oggetti e i piccoli vizi di un genitore la cui figura è forte e costante, una sicurezza che avvolge come una coperta morbida e calda; il bicchiere mezzo pieno indica un allontanamento momentaneo, un’assenza che paradossalmente è una preponderante presenza alla quale è impossibile pensare di rinunciare. Anche in questo caso la luce è essenziale perché infonde una sensazione di positività, di piacevolezza alla scena, lasciando intuire non un senso di nostalgia, piuttosto una necessità di non dimenticare mai quei particolari che vanno a strutturare la personalità di un uomo, al di là del suo volto e del suo aspetto fisico, perché ciò che conta è l’essenza, la spiritualità silenziosa che proprio da quel fermo immagine si sprigiona.

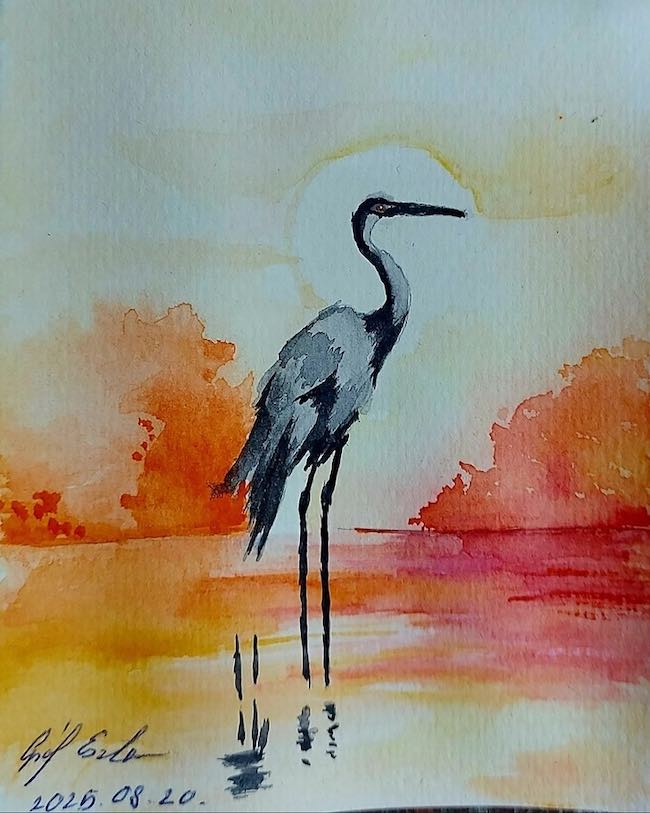

Piece appartiene invece all’approccio acquarellista di Eszter Gróf, sperimentato recentemente e che dona a questo tipo di lavori un aspetto più etereo, stilizzato, elimnando i dettagli e concentrandosi sulla rarefazione dell’atmosfera perché spesso ciò su cui lo sguardo ha bisogno di soffermarsi è l’impatto suggestivo. Qui la narrazione si perde completamente nello scorcio naturale che l’autrice rende protagonista, non ne sottolinea la realtà oggettiva, piuttosto mette in evidenza il senso di libertà, di leggerezza e di regalità che emana dall’airone e che si propaga all’ambiente circostante ammantandolo di magia; l’acquerello è molto sfumato, diluito proprio per assecondarsi all’intenzione espressiva dell’autrice.

Eszter Gróf, la cui formazione artistica è iniziata nel 2016, ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive in Ungheria e in Austria dove ha ricevuto consensi per il suo stile tradizionale nella forma e contemporaneo nel messaggio concettuale.

ESZTER GRÓF-CONTATTI

Email: eszter.grof@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/eszter.grof.54

Instagram: www.instagram.com/grofeszter_art/

The serenity of the slow pace of contemplation in Eszter Gróf’s classical Realism

Attempting to detach human beings from the hustle and bustle of contemporary life is a characteristic that belongs to visual art, as it requires an observational effort that goes beyond the initial impact and delves into meanings that are often hidden beneath the most superficial veil. the reflections induced by individual interpreters of contemporary painting and sculpture are more or less explicit based on the style they feel most akin to their expressive nature, but in all cases, connection and dialogue with emotion are essential for communicating with a viewer who needs to open up empathetically in order to grasp the message of the executor of an artwork. Today’s protagonist, through a traditional pictorial language, seems to want to invite the observer to distance himself from contingency by recreating the same contemplative atmospheres that belonged to past centuries, when progress had not distanced man from his existential tranquility and when slowness was imperative in order to savor life.

Around the early 19th century, some artists shifted their focus away from interiors and portraits of the aristocracy and royal families, as well as religious or mythological themes, which had been prevalent in previous painting, towards the representation of nature as a protagonist of great importance. This point of view emerged particularly with English Romanticism, where the impetuosity of atmospheric phenomena and stormy seas in the paintings of William Turner, who was the first to emphasize the relationship between the grandeur of nature and the insignificance of human beings, coexisted with the nostalgia evoked by the pure beauty of the countryside in the works of John Constable. It was clear with both artists that landscape would no longer be a secondary genre but had found its place in an artistic context undergoing rapid evolution, which was beginning to focus more attention on human beings and their deepest feelings, including those of the author which were reflected in the artwork. Already in the 18th century, the genre of Still life had carved out its own space, showing how even something that did not depict the human figure, although executed in pursuit of aesthetic perfection, carried with it a whole hidden range of emotions that permeated the works, revealing the inner life and sensitivity of the artists who chose those subjects. With the progressing of Nineteenth century gained ground Realism that on the one hand featured popular figures, farm workers who experienced contact with nature as part of their daily routine, on the other it represented a stylistic evolution in which was maintained figurative adherence to reality, much more than English Romanticism, even though it chose to distance from objectivity to enter the sphere of interpretation, that possibility for the artist to envelop the canvases with a softness that made the atmospheres suffused and velvety. The perfect synthesis of what has just been stated was achieved by the Barbizon School which combined the narration of the landscape with the subtle analysis of the society of the time, where many worked hard to enrich a few; but their study of reality did not dwell on social criticism rather simply tended to highlight the spontaneity and simplicity of the people’s lives, almost admiring their commitment and stoicism in facing daily hardships.

Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet showed how nature was no longer just a supporting actor to human beings, but a welcoming co-protagonist fundamental to daily existence; both, precisely because of their vision of the important role of nature, produced many still lifes in which emerged the vibrations of those familiar and reassuring moments, capturing the viewer’s gaze precisely because they were reminiscent of common sensations. The Hungarian artist Eszter Gróf shows an incredibly classical and traditional soul in her artistic production, drawing on the experiences of English Romanticism and the Barbizon School to highlight not only the objective importance of nature and its ability to protect and care for life, but also its existential relevance, since it is thanks to it, by contemplating it, that modern human beings can close the door to the outside world and immerse themselves in a still, motionless dimension, where there is no rush or frenzy to do anything. Taking a break, breathing a sigh of relief, and remembering the slow pleasure of everything that exists around everyday life are considered privileges by modern individuals, yet Eszter Gróf, with her expressive immediacy, manages to create still images that stimulate the unacknowledged need to rediscover the true essence, the deepest one, which can emerge only through contact with the primordial self. Her canvases are imbued with emotions, memories, references to something observed or seen at a particular moment or in specific circumstances, which become fixed in a closed drawer of emotional memory, relegated to a hidden corner; Eszter Gróf‘s innate ability is that of making them re-emerge thanks to her narratives of strong visual impact, because they tell and exalt the beauty of the observed reality, and to her natural mastery in impressing in that perfect aesthetic fragments of feelings that cannot help but come out enveloping the observer.

Her realistic style is mainly expressed through oil on wood, but recently Eszter Gróf has also been experimenting with watercolors, which lend a lyrical aura to her artworks. Moving effortlessly from still lifes to landscapes, the common denominator remains the conceptual intent to induce the viewer to understand the importance of contact, too often lost in modern life, with that slowed-down rhythm in which it is possible to question oneself, understand the real direction one’s soul would like to take, and get in touch with an authentic nature suffocated by the speed and urgency of the goals to be pursued. Királyrét Fishing Lake belongs to the more landscape-oriented side of Eszter Gróf and by immortalizing a glimpse of a lake in her beautiful country she manages to convey its calm, tranquility, and evocative silence which makes you want to enter that poetic and solitary atmosphere, almost as if your inner self knew it needed that moment of abstraction from the noise of the city. The light sculpts part of the pier and reflects on the water closest to the bottom of the lake, while the rest reflects the treetops on both banks; the feeling of immobility is emphasized and amplified by the total absence of human beings, as if any external element would break the wonderful balance that cradles the gaze. But the most intense lyricism of Eszter Gróf‘s painting is revealed in her still lifes, as in these works the artist inserts memories, recollections of something familiar, details that evoke scenes from everyday life and are left suspended, as if the protagonists had moved away to allow her to immortalize that fragment from which she lets herself be moved.

The painting Vili Papa (Papa Vili) speaks precisely of this, highlighting a habit, bringing together the objects and little vices of a parent whose figure is strong and constant, a security that envelops like a soft, warm blanket; the half-full glass indicates a momentary departure, an absence that paradoxically is an overwhelming presence that is impossible to imagine giving up. Here too, light is essential because it instills a feeling of positivity and pleasantness in the scene, suggesting not a sense of nostalgia but rather a need to never forget those details that shape a man’s personality, beyond his face and physical appearance because what matters is the essence, the silent spirituality that emanates from that still image. Piece on the other hand, belongs to Eszter Gróf‘s watercolor approach, recently experimented with, which gives this type of work a more ethereal, stylized appearance, eliminating details and focusing on the rarefaction of the atmosphere because often what the eye needs to linger on is the evocative impact. Here, the narrative is completely lost in the natural glimpse that the author makes the protagonist, she does not emphasize objective reality but rather highlights the sense of freedom, lightness, and royalty that emanates from the heron and spreads to the surrounding environment, cloaking it in magic; the watercolor is very nuanced, diluted precisely to accommodate the author’s expressive intention. Eszter Gróf, whose artistic training began in 2016, has participated in many group exhibitions in Hungary and Austria, where she has received acclaim for her traditional style in form and contemporary conceptual message.