Nel percorso di ciascun artista si svela soventemente l’attitudine a orientarsi verso il mondo naturale, oppure quello animale o ancora quello dell’essere umano con il suo sentire, le sue complessità, i suoi limiti e i suoi punti di forza; la protagonista di oggi al contrario si concentra sull’essere umano tanto quanto sul mondo animale sottolineando però le similitudini che esistono nelle espressioni e nei comportamenti che contraddistinguono sia l’uno che gli altri.

L’incontro tra questi due universi staccati eppure paralleli, quello umano e quello animale, ha cominciato a costituire un punto imprescindibile nella storia dell’arte in particolar modo dal Realismo in avanti, quando i ricchi committenti desideravano essere immortalati insieme ai loro amici a quattro zampe, quelli che riempivano le loro giornate e che non erano più solo mezzi per spostarsi come nel caso dei cavalli che in fondo venivano ritratti più come un contorno al protagonismo dell’uomo, bensì la loro rilevanza nella quotidianità cominciò a essere evidente. Con l’avvicinarsi del Novecento però l’universo faunesco ebbe via via maggiore spazio sia nell’Impressionismo di Pierre Auguste Renoir e di Giovanni Boldini, nelle cui scene domestiche venivano spesso immortalati cani e gatti come compagni imprescindibili della quotidianità dei loro protagonisti, sia nell’Espressionismo di Franz Marc che addirittura dedicò numerose tele agli animali escludendo la presenza umana, come se solo loro fossero simboli della purezza, della spontaneità che la società borghese degli inizi del Ventesimo secolo stava perdendo. Ma fu soprattutto il maestro Naïf Henri Rousseau a condurre l’osservatore verso un mondo sconosciuto, persino all’autore che dipingeva immaginando e sognando luoghi lontani mai visitati, costituito da giungla, da leoni, tigri, animali selvaggi attraverso i quali forse cercava una naturalezza e un’istintività sepolte dall’ipocrisia e dalle regole sociali della sua epoca. E infine come dimenticare il rapporto essenziale con gli animali della grande interprete del Surrealismo messicano Frida Kahlo, la quale amava ritrarsi immersa in quel mondo della giungla tanto appartenente al suo paese e che spesso diveniva un mezzo per evadere dalla solitudine del letto nel quale visse gran parte della sua gioventù a causa del grave incidente che quasi le costò la vita. In tutti questi grandi autori del passato vi era uno sguardo personale sul rapporto con la fauna, più concreto, rassicurante, oppure di evasione, di ammirazione ma sempre correlato all’essere umano o alle sensazioni dell’esecutore dell’opera.

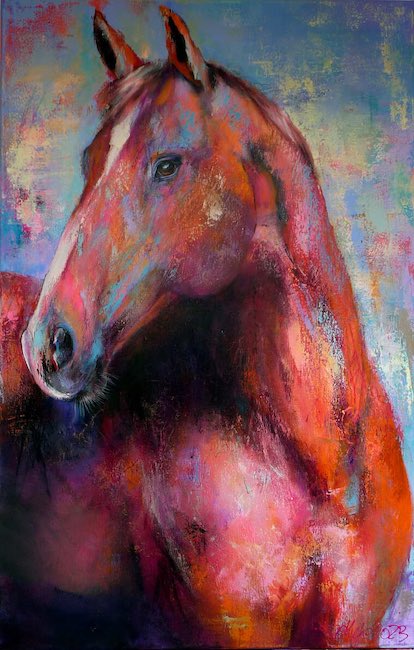

In Manuela Rathje invece l’approccio pittorico è differente perché lei si fa interprete di quelle piccole o grandi espressioni che costituiscono sia le donne che rende protagoniste di intensi ritratti, sia gli animali, di cui coglie l’intensità, la posa dolce, l’atteggiamento tranquillo che li contraddistingue e che mette in risalto in virtù della sua sensibilità, della sua capacità di cogliere quel particolare frangente in cui tutto si racchiude in uno sguardo, in una posa; apparentemente umanizzati dunque, le scimmie, i cavalli, i pappagalli, gli orsi, in realtà sono simboli di quelle emozioni spontanee che l’uomo ha perduto, perché troppo preso a mostrare il lato migliore di sé, quello estetico, quello in cui tutto deve apparire impeccabile per poter essere piacevole e accettato dal mondo esterno. Nell’universo faunistico di contro, non esiste il timore del giudizio, non c’è ricerca di accettazione forse piuttosto di amore, di genuinità e di immediatezza del vivere, del saper accogliere quell’universo di sensazioni che non ha bisogno di essere filtrato dalla razionalità o dall’esigenza di apparire perfetti; sembra quasi essere un suggerimento quello della Rathje a lasciarsi andare, a ricongiungersi con quel lato perduto che l’essere umano ha dimenticato ma che è essenziale a ritrovare la giusta dimensione del vivere.

Pertanto nelle sue opere l’animale non è più comprimario o specchio dell’uomo piuttosto una nuova guida nel tornare verso la naturalezza, verso quel modo di vivere più autentico che è essenziale a dare la priorità all’essere piuttosto che all’apparire. Lo stile pittorico di Manuela Rathje è intenso, affascinante per la sua capacità di mescolare un tratto realista a una gamma cromatica espressionista, irreale in alcuni tratti e armonizzata alle emozioni proprio perché funzionale a raccontare e mettere in evidenza il mondo interiore, la percezione e l’intensità dell’istante che la sua sensibilità empatica riesce a cogliere. Le sovrapposizioni degli strati di colore vengono successivamente strisciate per infondere nell’osservatore quel senso di graffiato che sembra scolpire ancor più la parte emozionale dell’opera lasciando però in evidenza quei dettagli fortemente attinenti alla realtà osservata fondamentali all’artista per sottolineare ed enfatizzare la sensazione che desidera emerga.

Quello della Rathje è un cammino di scoperta, di rivelazione di tutte le espressioni colte distrattamente che però possono trasformarsi in punti focali di una sua opera perché è proprio all’interno di quelle caratterizzazioni che si svela l’interiorità del personaggio, che sia esso umano o animale. Dunque da un lato l’osservatore è spinto a considerare ciò che vede sulla base del paradigma che vede l’uomo essere il centro di ogni termine di paragone in virtù della sua intelligenza definita come superiore; dall’altro però non può fare a meno di mettere in dubbio le sue certezze e domandarsi se tutto sommato gli animali non siano in fondo più intensi, più delicati nelle loro espressioni rispetto ai bellissimi volti di donne che sembrano dimenticare la sostanza per dare prevalenza alla forma. Un forma che per quanto perfetta, impeccabile ed esteticamente straordinaria, appartiene in ogni caso a un’essenza costituita da emozioni e sentimenti che Manuela Rathje porta alla luce attraverso quelle tonalità decontestualizzate con cui racconta le sue protagoniste, e che è irrinunciabile proprio perché parte dell’anima.

Questa sensazione emerge dall’opera Faces 12 dove la donna indossa occhiali da sole da cui è impossibile scorgere la sua espressione, ed è forse proprio questo a rendere quel volto apparentemente tanto sicuro di sé, eppure l’artista pone in risalto i tratti attraverso colori accesi, intensi, quasi volesse sottolineare il bisogno della donna di perdersi dentro un’allegria che abitualmente viene controllata per non apparire eccessiva, di lasciarsi andare all’entusiasmo trattenuto per mostrare di essere equilibrata. Le lenti azzurre riflettono un paesaggio ideale che può essere ricondotto a un sogno, al desiderio di trovarsi in un altro luogo, conosciuto o solo immaginato, ponendo l’accento su quanto un atteggiamento impertinente possa nascondere un mondo che si svela solo a chi è capace di guardare oltre l’immagine.

In alcune opere il magnetismo è completamente affidato allo sguardo, in altre invece gli occhi sono addirittura chiusi o non guardano direttamente l’osservatore, come nel dipinto Faces 10 dove la protagonista sembra talmente assorta nei suoi pensieri da dimenticare quella maschera con cui abitualmente protegge la sua interiorità lasciandosi cullare forse da un ricordo piacevole, proprio per sottolineare quanto anche un semplice gesto, una posa del capo o del corpo possano svelare di un essere vivente.

Nella tela Bonnie & Clyde i pappagalli protagonisti sono immortalati da Manuela Rathje durante un momento di dolcezza, di coccole che sottolineano quanto l’amore, l’unione, non siano prerogative dell’uomo bensì appartengano a tutti gli esseri viventi che molto spesso sono in grado di vivere ogni istante con una maggiore spontaneità, senza le numerose problematiche che la razionalità pone tra le persone e la loro possibilità di essere felici. I due pappagalli sono vicini ma sembrano scrutare l’osservatore, come a volerlo condurre all’interno del loro mondo fatto di sentimenti positivi, come se volessero invitarlo a immergersi a sua volta dentro un universo differente, sereno, positivo e infinitamente più semplice.

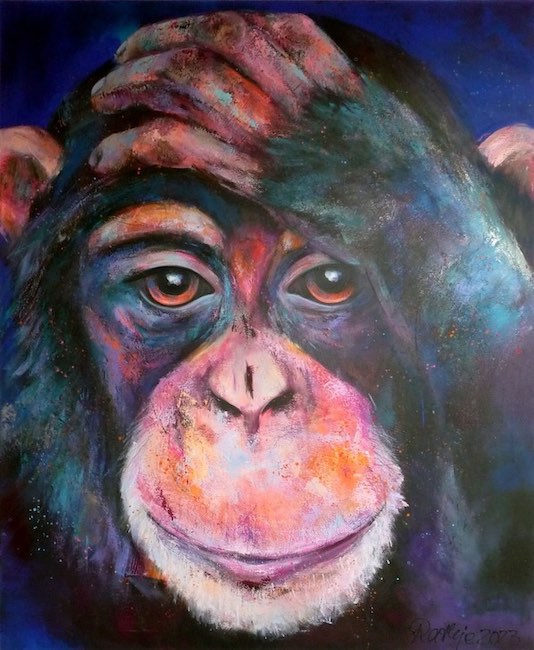

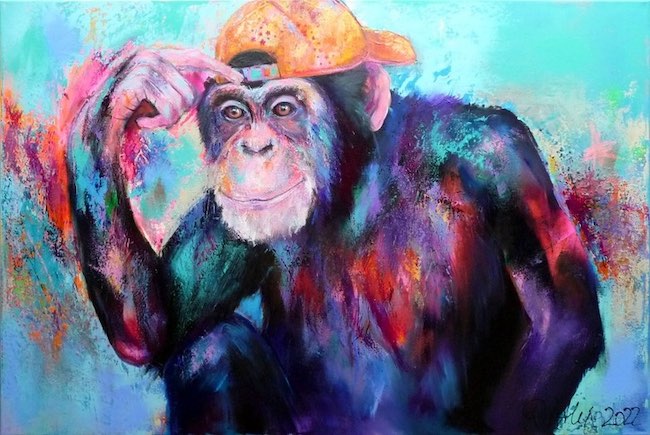

E ancora in What do you think about us, uno scimpanzé imita le sembianze umane rivolgendo una domanda che da un lato ne svela l’innata curiosità, dall’altro spinge verso la riflessione su quanto in fondo il mondo animale osservi l’uomo e in qualche modo desideri, e in alcuni casi abbia bisogno, di interagire con lui, forse consapevole di essere un importante mezzo per ricordargli di non perdere mai la sua umanità intesa come capacità di emozionarsi, di provare tenerezza, di coltivare i sentimenti più puri e di prendersi cura della propria interiorità, non solo della forma esteriore. Oppure al contrario, la domanda dell’artista è rivolta allo scimpanzé, è come se volesse chiedergli cosa pensa dell’essere umano con cui è costretto a convivere e ad avere a che fare, ed è questo forse il motivo dell’espressione assorta dell’animale, come se stesse cercando una risposta. Manuela Rathje ha al suo attivo molte mostre personali e collettive in Germania e all’estero – Usa, Olanda, Svizzera, Egitto – che le hanno permesso nel tempo di essere notata da collezionisti e addetti ai lavori.

MANUELA RATHJE-CONTATTI

Email: info@manuela-rathje.de

Sito web: www.manuela-rathje.de/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/manuela.rathje.3

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/manuela.rathje/

Manuela Rathje’s Realist Expressionism, when the protagonists are living beings in their multifaceted and individual personalities

Each artist’s career often reveals an attitude towards the natural world, or the animal world, or even the human world with its feelings, complexities, limits and strengths; today’s protagonist, on the contrary, focuses on the human being as much as on the animal world, emphasising, however, the similarities that exist in the expressions and behaviour that distinguish both the one and the other.

The encounter between the two detached yet parallel universes, the human and animal one, began to constitute an unavoidable point in the history of art, especially from Realism onwards, when wealthy patrons wished to be immortalised together with their four-legged friends, those who filled their days and who were no longer merely means of getting around as in the case of horses, which were basically portrayed more as a side dish to man’s prominence, but their relevance in everyday life began to be evident. With the approach of the 20th century, however, the faunal universe was gradually given more and more space both in the Impressionism of Pierre Auguste Renoir and Giovanni Boldini, in whose domestic scenes dogs and cats were often immortalised as indispensable companions in the everyday life of their protagonists, and in the Expressionism of Franz Marc, who even dedicated numerous canvases to animals to the exclusion of the human presence, as if only they were symbols of purity, of the spontaneity that the bourgeois society of the early 20th century was losing. But it was above all the Naïf master Henri Rousseau who led the observer to a world unknown, even to the author, who painted imagining and dreaming of distant places he had never visited, made up of jungles, lions, tigers, wild animals through which he perhaps sought a naturalness and instinctiveness buried by the hypocrisy and social rules of his era. And finally, how can we forget the essential relationship with animals of the great interpreter of Mexican Surrealism, Frida Kahlo, who loved to portray herself immersed in that world of the jungle that belonged so much to her country and that often became a means of escape from the solitude of the bed in which she lived much of her youth due to the serious accident that almost cost her her life.

In all these great authors of the past, there was a personal view of the relationship with fauna, either more concrete, reassuring, or of evasion, of admiration, but always related to the human being or to the feelings of the author of the artwork. In Manuela Rathje, on the other hand, the pictorial approach is different because she makes herself the interpreter of those small or large expressions that make up both the women that she makes the protagonists of intense portraits, and the animals, whose intensity, gentle pose and calm attitude she captures and which she emphasises by virtue of her sensitivity, her ability to capture that particular juncture in which everything is enclosed in a glance, in a pose; apparently humanised then, monkeys, horses, parrots, bears, are in reality symbols of those spontaneous emotions that man has lost, because he is too busy showing the best side of himself, the aesthetic side, the side in which everything must appear impeccable in order to be pleasing and accepted by the outside world. In the universe of animals, on the other hand, there is no fear of judgement, there is no search for acceptance, perhaps rather for love, for genuineness and immediacy of living, for knowing how to welcome that universe of sensations that does not need to be filtered by rationality or by the need to appear perfect; it almost seems to be a suggestion by Rathje to let oneself go, to reconnect with that lost side that the human being has forgotten but that is essential to rediscovering the right dimension of living. Therefore, in her artworks, the animal is no longer the comprimario or mirror of man, but rather a new guide in returning towards naturalness, to that more authentic way of living that is essential to prioritising being rather than appearing. Manuela Rathje‘s painting style is intense, fascinating for its ability to mix a realist stroke with an expressionist chromatic range, unreal in some strokes and harmonised with the emotions precisely because it is functional to narrate and highlight the inner world, the perception and intensity of the instant that her empathic sensitivity manages to capture.

The superimpositions of the layers of colour are subsequently swiped to instil in the observer that sense of scratchiness that seems to sculpt the emotional part of the work even more, while leaving in evidence those details that are strongly pertinent to the observed reality that are fundamental for the artist to underline and emphasise the sensation she wishes to emerge. Rathje‘s is a path of discovery, of revelation of all the expressions caught absent-mindedly, which can however become the focal points of her artworks because it is precisely within those characterisations that the interiority of the character, whether human or animal, is revealed. So on the one hand, the observer is prompted to consider what he sees on the basis of the paradigm that sees man as the centre of all terms of comparison by virtue of his intelligence defined as superior; on the other hand, however, he cannot help but question his certainties and wonder whether animals are not after all more intense, more delicate in their expressions than the beautiful faces of women who seem to forget substance in order to give prevalence to form. A form that, however perfect, impeccable and aesthetically extraordinary, in any case belongs to an essence made up of emotions and feelings that Manuela Rathje brings to light through those decontextualised tones with which she depicts her protagonists, and which is inalienable precisely because it is part of the soul. This sensation emerges from the work Faces 12 where the woman wears sunglasses from which it is impossible to make out her expression, and it is perhaps this that makes that face apparently so self-confident, yet the artist emphasises the features through bright, intense colours, almost as if she wanted to emphasise the woman’s need to lose herself in a cheerfulness that is usually controlled so as not to appear excessive, to let herself go in restrained enthusiasm to show that she is balanced. The blue lenses reflect an ideal landscape that can be traced back to a dream, to the desire to be in another place, known or only imagined, emphasising how an impertinent attitude can conceal a world that is only revealed to those capable of looking beyond the image.

In some artworks, magnetism is completely entrusted to the gaze, while in others the eyes are even closed or do not look directly at the observer, as in the painting Faces 10, where the protagonist seems so absorbed in her thoughts that she forgets the mask with which she usually protects her interiority, perhaps allowing herself to be lulled by a pleasant memory, precisely to emphasise how even a simple gesture, a pose of the head or body can reveal the identity of a living being. In the painting Bonnie & Clyde, the parrots are immortalised by Manuela Rathje during a moment of sweetness, of cuddling, underlining how love, union, are not the prerogatives of man but belong to all living beings who are very often able to live each moment with greater spontaneity, without the many problems that rationality poses between people and their possibility of being happy. The two parrots are close by but seem to peer at the observer, as if to lead him into their world of positive feelings, as if to invite him to immerse himself in turn into a different, serene, positive and infinitely simpler universe. And again in What do you think about us, a chimpanzee imitates human features, asking a question that on the one hand reveals its innate curiosity, and on the other prompts reflection on how much the animal world basically observes man and in some ways desires, and in some cases needs, to interact with him, perhaps aware that it is an important means of reminding him never to lose his humanity, understood as the capacity to be moved, to feel tenderness, to cultivate the purest of feelings and to take care of his own, to interact with him, perhaps aware that it is an important means of reminding him never to lose his humanity, understood as the capacity to be moved, to feel tenderness, to cultivate the purest feelings and to take care of his inner self, not just his outer form. Or on the contrary, the artist’s question is addressed to the chimpanzee, it is as if she wanted to ask it what it thinks of the human being it is forced to live with and deal with, and this is perhaps the reason for the animal’s absorbed expression, as if it were searching for an answer. Manuela Rathje has many solo and group exhibitions to her credit in Germany and abroad – USA, Holland, Switzerland, Egypt – which have enabled her over time to be noticed by collectors and art professionals.