A volte la ricerca di un artista contemporaneo può spingersi a voler reinterpretare, celebrandola, una parte della storia più recente da cui ha attinto e trovato ispirazione per elaborare il proprio stile pittorico; in alcuni casi questo tipo di analisi si spinge fino al punto di dedicare un percorso di approfondimento focalizzandosi su tutto ciò che quell’avanguardia del passato ha lasciato alla generazione successiva, e decidendo di andare a scoprire di più sulle origini e sulle radici che hanno permesso la generazione dell’innovazione che ne è stata generata. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi basa la sua produzione pittorica su uno stile affascinante quanto inusuale nella contemporaneità, dando vita così a una personalizzazione innovativa e coinvolgente, ed analizzando tutte le basi da cui le linee guida principali si sono sviluppate.

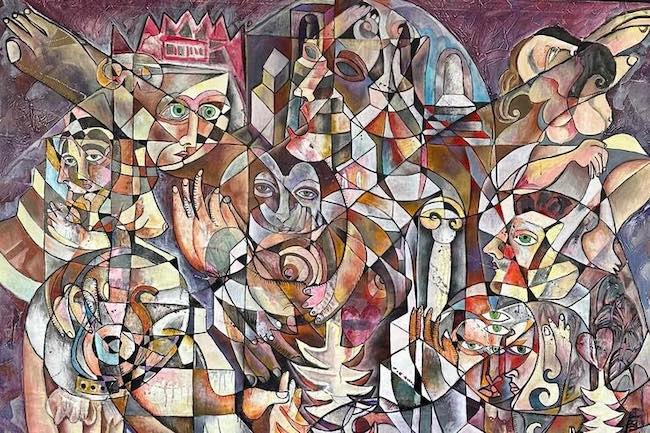

Il primo ventennio del Novecento ha visto affermarsi, consolidarsi ed espandersi tutte quelle teorie sulla scomposizione dell’immagine anticipate verso la fine dell’Ottocento dall’Impressionismo e poi proseguite con il Puntinismo e il Divisionismo; sebbene questi movimenti si basassero infatti solo sulla frammentazione del colore per ottenere una migliore resa della luce e della definizione rinunciando alla tradizionale esecuzione accademica, tuttavia l’analisi sulla suddivisione del visibile era avviata. Le successive avanguardie dei primi decenni del nuovo secolo si spinsero ben oltre, ampliando la tematica della suddivisione per dare una struttura geometrica ma al contempo dinamica alla realtà riprodotta o immaginata che era protagonista delle loro opere. Da un lato il Futurismo con la sua idea di velocità, di progresso, per cui l’arte doveva adeguarsi ai tempi e stare al passo con quella fiducia verso il futuro sottolineato dalle nuove scoperte tecnologiche, meccaniche, scientifiche seguite alla rivoluzione industriale; dall’altro invece il Cubismo che proponeva una visione distorta dell’osservato, scomponendo volti, paesaggi, situazioni, per guardarne contemporaneamente tutte le sfaccettature, i lati, eliminando la prospettiva e la terza dimensione e proponendo un insolito punto di osservazione. Il fondatore del Cubismo, Pablo Picasso, giunse alla elaborazione dello stile che lo rese famoso dopo un inizio artistico più classicamente figurativo che ben presto però trovò interessanti spunti in quel Primitivismo che affascinò anche altri suoi coevi come Amedeo Modigliani. I primi passi nel Cubismo furono infatti rappresentati dall’opera Les Demoiselles d’Avignon dove le influenze delle maschere africane nei volti delle donne raffigurate erano particolarmente evidenti e non ancora contraddistinti dalla successiva estremizzazione della scomposizione che fu il tratto distintivo del suo secondo importante periodo pittorico, quando cioè cominciò a essere più audace e la frammentazione più evidente per infondere nell’osservatore la sensazione dello scorrere del tempo, della possibilità di avere di fronte nello stesso momento differenti impressioni ricevute della realtà. In un certo senso la ricerca cubista attinse alle tematiche futuriste nella rappresentazione formale differenziandosi però nella sostanza poiché laddove i secondi volevano imprimere nelle tele la velocità e l’accelerazione entusiasta nei confronti delle nuove scoperte e del modo di vivere, i primi invece, Picasso e Braque in special modo, puntavano a scoprire la possibilità della contemporaneità delle sfaccettature dei loro soggetti, mettendo tutte le dimensioni sul medesimo piano. L’artista di origine cubana, ma ormai da molti anni residente a Madrid, Felipe Alarcón Echenique compie una completa rivisitazione del Cubismo, assecondandolo alla sua poetica espressiva e riattualizzandolo sulla base della propria inclinazione pittorica che lo induce ad arricchire le sue tele di quei simboli latino americani appartenenti alla sua cultura, ma introducendo anche l’elemento espressionista che si concretizza con il disegno con il quale l’artista sembra voler restare fortemente connesso con le sue radici.

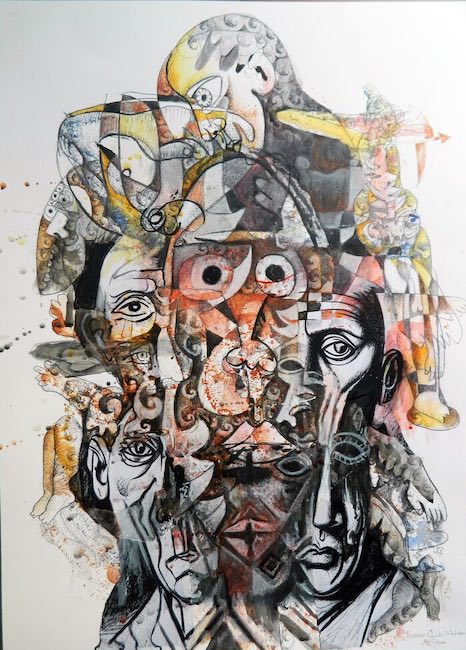

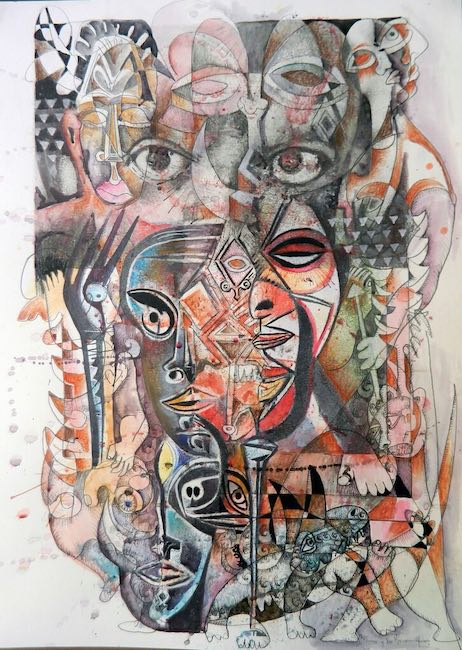

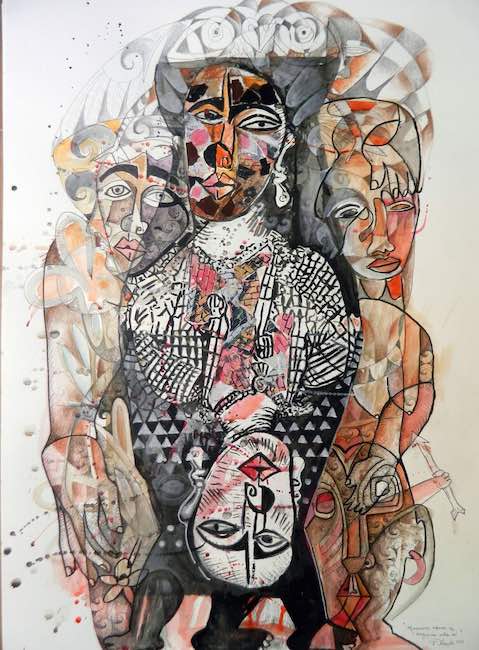

Dunque l’Espressionismo viene sottoposto e lasciato quasi in trasparenza rispetto al Neocubismo, come se Felipe Alarcón Echenique volesse raccontare tutto ciò che appartiene alla sua realtà, alle origini del suo popolo, alle influenze dei conquistadores sugli indigeni e sugli africani trasferiti nell’isola per servire gli spagnoli, ma poi si sposta a sottolineare quanto nell’epoca contemporanea tutto questo sia superato passando allo strato superiore in cui i tratti cubisti, a volte persino troppo geometrici, in lui sono ammorbiditi, più tondeggianti, meno estremi.

La gamma cromatica delle sue opere è sfumata, terrosa, in trasparenza per quanto riguarda i sottostanti disegni e più intensa invece nelle figure in primo piano, come se il sottostrato dell’opera costituisse la memoria di tutte le voci, di tutte le esperienze e delle difficoltà incontrate da un passato superato eppure elemento fondante dell’esistenza presente. Nella nuova serie pittorica Felipe Alarcón Echenique ha compiuto un’affascinante ricerca su Pablo Picasso, padre del Cubismo e dunque anticipatore di quello che è il linguaggio pittorico attraverso cui egli ha scelto di esprimersi, compiendo un vero e proprio cammino all’interno della vita personale e artistica del grande maestro spagnolo.

Ciò che emerge dalla serie Picasso Mestizo è proprio l’origine della pittura del maestro del Novecento, quell’attingere a un Primitivismo marcato, ispiratore, che non ha mai abbandonato la sua produzione tanto quanto quella di Felipe Alarcón Echenique; la razza meticcia è in fondo quella in grado di unire davvero le culture, di mantenere memoria di entrambe le origini e di dare vita a una fusione che sempre è dominante, fortemente presente in ogni opera di Alarcón Echenique, così come fu la base da cui partì Picasso per elaborare il suo stile pittorico.

L’opera La creación del cubismo mestizo mostra quanto da un lato sia fortemente presente il riferimento al maestro del Cubismo, dall’altro quanto invece vi sia di rielaborazione e personalizzazione da parte di Felipe Alarcón Echenique, come se l’ispirazione, rappresentata dalle parti in scala di grigio al centro, si fosse mescolata a una poetica espressiva che non può non attingere a una terra, quella cubana, in cui forse più che in qualunque altro luogo, convivono da sempre usi e costumi differenti che hanno saputo arricchirsi vicendevolmente in virtù di quella stretta vicinanza. Le figure rappresentano gli antichi conquistatori spagnoli tanto quanto gli africani importati per essere schiavi, e tutti si trovano sullo stesso livello, come se di fatto non vi fosse contrapposizione tra diverse origini bensì solo la consapevolezza di avere il compito di mescolarsi per creare un mondo inclusivo e accogliente.

In Picasso y las máscaras africanas invece, Felipe Alarcón ripercorre quel cammino di evoluzione dello stile pittorico dell’artista iberico, quella fase durante la quale si lasciò affascinare, come tutti i frequentatori dei salotti parigini, dall’immediatezza e dal forte legame con gli istinti e le passioni caratteristiche dei popoli indigeni del sud del mondo, dalle maschere tribali stilizzate e ridotte all’essenziale; questo avvicinamento all’arte africana diede vita all’innovazione costituita dal Cubismo e con Alarcón Echenique si estende, parla delle di tutti gli elementi, mescolati nell’opera per attrarre l’attenzione dell’osservatore il quale desidera scovare ogni singolo dettaglio, ogni riferimento che fuoriesce solo dopo un secondo o un terzo sguardo, dando vita alla medesima curiosità di scoperta che aveva contraddistinto Picasso e che aveva suscitato l’attenzione nei confronti di un tipo di rappresentazione iconografica sconosciuta fino a poco prima eppure in grado di mostrare al mondo cosiddetto civilizzato quanto tutto possa essere più semplice, meno formale e spesso falso.

Il supporto molte opere della serie Picasso Mestizo è il cartone, dove il disegno rimane nitido, incisivo, facendo sentire la sua voce malgrado poi le figure che lo sovrastano siano contraddistinte da una gamma cromatica più intensa, seppur sempre legata ai colori della terra, di quelle origini indigene da cui Felipe Alarcón Echenique non riesce a prescindere e di cui Picasso ha sempre subito il fascino.

L’artista contemporaneo dunque rende omaggio al suo maestro ispiratore senza il timore di confrontarsi con lui anzi, forse è proprio in virtù della sua forte e spiccata personalità espressiva che lo rende unico nel panorama artistico attuale, che è in grado di mettersi in gioco e raccontare tutto ciò che ha contribuito a permettergli di raggiungere la sua maturità artistica, compreso dunque anche il suo maggior ispiratore. Felipe Alarcón Echenique ha al suo attivo mostre personali e collettive a Cuba e a Madrid, le sue due patrie, ma anche in tutto il mondo – Italia, Guatemala, Stati Uniti, Argentina, Canada, Cina, Svezia, Portogallo, Costa Rica, Germania, Regno Unito, Francia -; ha vinto numerosi premi d’arte e le sue opere sono visibili in musei e ambasciate di tutto il mondo.

FELIPE ALARCÓN-CONTATTI

Email: aechenique2003@yahoo.com

Sito web: www.f-alarcon.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/felipe.alarconechenique

Instagram: www.instagram.com/felipealarconoficial/

The Neocubist language of Felipe Alarcón Echenique, exploring the influences of the original movement and celebrating its greatest exponent

Sometimes the research of a contemporary artist may go so far as to want to reinterpret, and celebrate, a part of more recent history from which he has drawn and found inspiration to elaborate his own pictorial style; in some cases, this type of analysis goes so far as to devote an in-depth path focusing on all that that avant-garde of the past has left to the next generation, and deciding to go and discover more about the origins and roots which allowed the generation of innovation that was generated. The artist I am going to tell you about today bases his painting production on a style that is as fascinating as it is unusual in the contemporary world, thus giving rise to an innovative and engaging personalisation, and analysing all the bases from which the main guidelines developed.

The first two decades of the 20th century saw the affirmation, consolidation and expansion of all those theories on the subdivision of the image anticipated towards the end of the 19th century by Impressionism and then continued with Pointillism and Divisionism; although these movements were in fact based only on the fragmentation of colour to obtain a better rendering of light and definition, renouncing traditional academic execution, nevertheless the analysis on the subdivision of the visible was underway. The subsequent avant-gardes of the first decades of the new century went much further, expanding the theme of subdivision to give a geometric yet dynamic structure to the reproduced or imagined reality that was the protagonist of their artworks. On the one hand, Futurism with its idea of speed, of progress, for which art had to adapt to the times and keep up with that confidence in the future underlined by the new technological, mechanical, scientific discoveries following the industrial revolution; on the other hand, Cubism, which proposed a distorted vision of the observed, breaking down faces, landscapes, situations, to look at all their facets, sides, at the same time eliminating perspective and the third dimension and proposing an unusual point of observation.

The founder of Cubism, Pablo Picasso, arrived at the elaboration of the style that made him famous after a more classically figurative artistic beginning that soon however found interesting cues in that Primitivism that also fascinated other of his contemporaries such as Amedeo Modigliani. His first steps into Cubism were in fact represented by the work Les Demoiselles d’Avignon where the influences of African masks in the faces of the women depicted were particularly evident and not yet characterised by the later extreme decomposition that was the hallmark of his second important pictorial period, when he began to be more daring and the fragmentation more evident in order to instil in the observer the sensation of the passage of time, of the possibility of having in front of him at the same time different received impressions of the reality. In a certain sense, Cubist research drew on Futurist themes in formal representation, but differing in substance, since while the latter wanted to imprint their canvases with speed and enthusiastic acceleration towards new discoveries and ways of life, the former, Picasso and Braque in particular, aimed to discover the possibility of the contemporaneity of the facets of their subjects, placing all dimensions on the same plane. The artist of Cuban origin, but resident in Madrid for many years, Felipe Alarcón Echenique performs a complete reinterpretation of Cubism, bringing it into line with his expressive poetics and updating it on the basis of his own pictorial inclination that leads him to enrich his canvases with those Latin American symbols belonging to his culture, but also introducing the expressionist element that takes the form of drawing with which the artist seems to want to remain strongly connected to his roots.

Thus, Expressionism is subjected to and left almost in transparency with respect to Neo-Cubism, as if Felipe Alarcón Echenique wanted to recount everything that belongs to his reality, the origins of his people, the influences of the conquistadors on the natives and Africans who moved to the island to serve the Spaniards, but then he moves on to emphasise how in contemporary times all this is outdated by moving to the upper layer in which the Cubist strokes, at times even too geometric, are softened, more rounded, less extreme in him. The chromatic range of his artworks is shaded, earthy, transparent in the underlying drawings and more intense in the foreground figures, as if the sublayer of the artwork constitutes the memory of all the voices, of all the experiences and difficulties encountered from an outdated past and yet a founding element of present existence. In the new pictorial series, Felipe Alarcón Echenique has carried out a fascinating research on Pablo Picasso, the father of Cubism and thus the forerunner of the pictorial language through which he chose to express himself, making a true journey through the personal and artistic life of the great Spanish master.

What emerges from the Picasso Mestizo series is precisely the origin of the twentieth-century master’s painting, that drawing on a marked, inspirational Primitivism that has never abandoned his production as much as that of Felipe Alarcón Echenique; the mestizo race is, after all, the one capable of truly uniting cultures, of preserving the memory of both origins and giving life to a fusion that is always dominant, strongly present in every work by Alarcón Echenique, just as it was the basis from which Picasso started to elaborate his pictorial style. The painting La creación del cubismo mestizo shows how much reference to the master of Cubism is strongly present on the one hand, and on the other how much reworking and personalisation there is on the part of Felipe Alarcón Echenique, as if inspiration, represented by the grey-scaled parts in the centre, had mixed with an expressive poetics that cannot fail to draw on a land, the Cuban one, in which, perhaps more than anywhere else, different customs and traditions have always coexisted and enriched each other by virtue of that close proximity. The figures represent the ancient Spanish conquerors as much as the Africans imported to be slaves, and all are on the same level, as if in fact there were no opposition between different origins but only an awareness of the task of mixing to create an inclusive and welcoming world. In Picasso y las máscaras africanas, on the other hand, Felipe Alarcón retraces that path of evolution of the Iberian artist’s painting style, that phase during which he allowed himself to be fascinated, like all frequenters of the Parisian salons, by the immediacy and strong link with the instincts and passions characteristic of the indigenous peoples of the global south, by the stylised tribal masks reduced to the essential; this approach to African art gave rise to the innovation constituted by Cubism, and with Alarcón Echenique it is extended, it speaks of all the elements, mingled in the artwork to attract the attention of the observer who wants to unearth every single detail, every reference that only emerges after a second or third glance, giving rise to the same curiosity of discovery that had characterised Picasso and that had aroused attention towards a type of iconographic representation unknown until recently and yet capable of showing the so-called civilised world how much simpler, less formal and often false everything can be. The support of many of Picasso Mestizo paintings is cardboard, where the drawing remains sharp, incisive, making its voice heard despite the fact that the figures above it are characterised by a more intense chromatic range, although still linked to the colours of the earth, of those indigenous origins from which Felipe Alarcón Echenique cannot do without and which Picasso has always been fascinated by. The contemporary artist therefore pays homage to his inspiring master without fearing to confront him; on the contrary, perhaps it is precisely because of his strong and distinct expressive personality that makes him unique in today’s artistic panorama, that he is able to put himself on the line and recount everything that has contributed to allowing him to reach his artistic maturity, including therefore also his greatest inspirer. Felipe Alarcón Echenique has solo and group exhibitions to his credit in Cuba and Madrid, his two homelands, as well as all over the world – Italy, Guatemala, United States, Argentina, Canada, China, Sweden, Portugal, Costa Rica, Germany, United Kingdom, France -; he has won numerous art prizes and his artworks can be seen in museums and embassies all over the world.