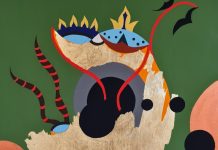

La necessità di evadere dalla realtà induce alcuni artisti a immaginare mondi paralleli dove tutto ha una dimensione differente, dove ogni cosa ha un’apparenza in grado di ingannare lo sguardo per il suo senso di familiarità conducendo però un attimo dopo verso una configurazione completamente destabilizzante rispetto a ciò che ci si aspetterebbe; in altri casi invece, pur rifacendosi a qualcosa di conosciuto, questo tipo di creativi riesce a infondere nei lavori un aspetto misterioso, suscitando un’apprensione per l’incognita di ciò che all’interno di quelle ambientazioni potrebbe emergere da un momento all’altro. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi delinea un universo che si allaccia fortemente all’osservato, mostrando dunque una realtà possibile, per poi infonderlo di una serie di sfaccettate altre opzioni che in qualche modo attraggono per l’estetica ma a un secondo sguardo appaiono in alcuni casi inquietanti turbando la prima sensazione ricevuta.

Ogni volta in cui le circostanze esistenziali divenivano intollerabili o frutto di ansie e frustrazioni, alcuni artisti rispondevano creando un tipo di pittura fuori dagli schemi, irreale, irriverente, sovversiva a volte, proprio per affrontare quei demoni esterni, quelle angosce a cui l’essere umano si assuefaceva senza essere in grado di prendere in mano la sua vita; alla fine del Quattrocento, poco dopo che l’Europa fu uscita dal Medioevo e cominciarono a delinearsi scissioni all’interno della Chiesa, e di conseguenza modi diversi di affrontare le questioni esistenziali ed etiche, Hieronymus Bosch diede vita a un mondo irreale e pieno di simboli che volevano costituire una critica alla rigida morale religiosa ancora dominante la quale non faceva che provocare nell’uomo frustrazioni nei confronti di pulsioni che comunque continuavano a esistere. Con le sue tele irreali, legate ai temi dell’aldilà, del giudizio, del peccato, come l’opera Il giardino delle delizie, e componendo paesaggi confusi dove nascondeva allegorie e messaggi subliminali del suo pensiero, Bosch divenne di fatto anticipatore di un movimento che si sviluppò cinque secoli dopo, il Simbolismo, e che ebbe in Odilon Redon uno degli esponenti più estremi, in particolar modo nella figurazione dei lavori grafici; occhi fluttuanti, fiori inquietanti, animali con volto umano, queste furono le caratteristiche distintive di uno dei maestri del movimento. Entrambe queste voci artistiche fuori dal coro gettarono le basi per l’evoluzione successiva, quella che si concretizzò agli inizi del Novecento con il Surrealismo, corrente che seguendo gli studi sull’inconscio dello psicanalista Sigmund Freud, mise in luce la parte onirica, le angosce, le ansie paralizzanti dentro cui la mente si rinchiudeva liberandosi nella fase del sonno; Salvador Dalì con il suo mondo fatto di tempo liquido, di animali improbabili, di dettagli umani nascosti nelle pieghe della realtà e con l’ossessione della sessualità sempre presente, Max Ernst con i paesaggi post-apocalittici, inquietanti scomposizioni di parti umane trasformate e poi nascoste tra fitta vegetazione, la narrazione dei personaggi sulla base delle loro caratteristiche più irritanti, erano entrambi interpreti di quell’universo spaventoso degli incubi che affliggevano gran parte della società a seguito degli orrori della prima guerra mondiale, ma anche di tutte le pulsioni più segrete e inconfessabili dell’uomo che dovevano fuoriuscire e liberarsi. Il Surrealismo ha avuto verso la fine del Ventesimo secolo interessanti evoluzioni che da un lato hanno proseguito seguendo il filone più sognante e fiabesco, come nel caso di Vladimir Kush, dall’altro invece si sono orientati verso il mistero, l’enigma e l’inquieta apparente normalità trasformata in angosciante opzione di realtà, come nel Pop Surrealismo.

L’artista statunitense Shara Hughes attinge per elaborare il suo stile al lato più naturalista di Max Ernst, riproponendo la fitta vegetazione in mezzo alla quale però non pone figure pseudo umane, non inserisce simboli, bensì semplicemente dona un punto di vista cangiante, mutevole e ingannevole che induce l’osservatore ad avvicinarsi in virtù dell’apparenza armonica delle ambientazioni narrate; ma poi, una volta che l’occhio si sofferma sui dettagli e si avvicina alle immagini fuoriesce invece un’irrealtà di fondo, una sottile inquietudine attraverso cui l’interiorità indugia sulle implicazioni del trovarsi all’interno di quel mondo fantastico, sulla possibilità che non tutto possa avere il risvolto piacevole e ludico evocato a primo impatto.

I fiori sembrano piante carnivore, in immobilità apparente ma pronte a sferrare il morso che poi fagociterà il malcapitato osservatore che dunque riceve una sensazione di attrazione e subito dopo di repulsione; lo stile pittorico è in alcuni casi vicino al Surrealismo poiché la definizione e la descrizione è perfettamente reale, in altri invece si sposta verso l’Espressionismo per la gamma cromatica, per l’assenza di chiaroscuro e di profondità, come se il racconto paesaggistico avesse bisogno di entrare in una dimensione incantata per poter esprimere le sensazioni che Shara Hughes desidera lasciar fuoriuscire. La scelta delle tonalità diviene dunque funzionale non tanto a liberare i moti interiori dell’artista, piuttosto a condurre l’osservatore all’interno della scenografia più affine all’universo del viaggio che di volta in volta viene intrapreso e in cui il fruitore viene inevitabilmente coinvolto; l’inganno visivo infatti induce a credere di essere di fronte a ricordi fanciulleschi, a momenti di osservazione di un mondo naturale tutto da scoprire, con la medesima meraviglia dei bambini che possono interpretare ogni momento come un’avventura meravigliosa.

In Pop infatti i dettagli del gambo del papavero sono ingranditi nelle dimensioni, così come il fiore, quasi come se Shara Hughes volesse raccontare un mondo lillipuziano dal quale tutto sembra talmente gigante da assumere l’aspetto di una foresta, pur trattandosi evidentemente solo di un campo di fiori; è questo il gioco magico che compie l’artista in ogni dipinto, conduce lo sguardo dentro un c’era una volta che sembra essere l’inizio di una fiaba e che, come ogni fiaba che si rispetti, presenta anche l’elemento spaventoso, la sensazione di pericolo imminente che può sopraggiungere a disturbare il percorso del protagonista.

In Hard hats la sensazione è quella di trovarsi di fronte a una vorace pianta carnivora, inattaccabile proprio in virtù delle coriacee corolle dentro le quali potrebbe far sparire un insetto, un animale o un piccolo uomo; qui l’atmosfera è più cupa, la gamma cromatica è più scura e ombrosa e di conseguenza l’aspetto generale della tela è meno ingannevolmente rassicurante rispetto alla precedente. Tutto sembra essere presagio di disavventure, persino il cielo, in stile decisamente espressionista come d’altronde anche lo sfondo del paesaggio, richiama la tempesta, quasi volesse mettere in guardia da un potenziale pericolo imminente; così la sensazione di attrazione nei confronti degli ambienti incantati di Shara Hughes, diviene in questo caso desiderio di restare al di fuori, di osservare la lontano anziché immergersi nell’atmosfera narrata come invece accade nel polittico The bridge.

In questa opera costituita da quattro grandi tele l’artista descrive un panorama che sembra essere uscito da un racconto fantastico, dove i colori rappresentano lo svolgersi dell’inizio della storia, come se ogni tonalità fosse una parola attraverso cui la scena si manifesta all’osservatore; l’Espressionismo è evidente nella scelta dei colori che tendono a confondere la realtà, o forse sarebbe meglio dire che vanno a generare un’altra realtà altrettanto possibile, dove le acque possono essere a tratti bianche a tratti colorate dal tramonto del sole anche quando non si trovano direttamente toccate dai suoi raggi.

I prati e le colline sono a loro volta completamente improbabili dal punto di vista coloristico ma nell’intento pittorico dell’artista quella rappresentata è la magia del sole in grado di modificare completamente il punto di vista; man mano che ci si allontana dalla sua azione però il paesaggio diventa scuro, avvolto dalle ombre della notte già sopraggiunta, e la natura, i fiori stessi, sembrano essere in procinto di addormentarsi in attesa di un nuovo giorno.

Nella tela più a destra addirittura le corolle perdono la sembianza floreale e volgono verso una maggiore indefinitezza, sembrano chinarsi o chiudersi in se stesse per proteggersi dal freddo e dall’oscurità che sta per avvolgere quell’affascinante paesaggio. L’alternanza tra desiderio di entrare nelle scene raccontate e la contrastante tendenza ad allontanarsene costituisce il fascino delle opere di Shara Hughes, artista di fama internazionale che ha al suo attivo mostre personali e collettive in importanti sedi istituzionali di tutto il mondo – Danimarca, Svizzera, Francia, USA, Cina, Regno Unito – e le sue tele fanno parte delle collezioni pubbliche di musei in USA e in Cina.

SHARA HUGHES-CONTATTI

Email: info@davidkordanskygallery.com

Sito web: www.davidkordanskygallery.com/exhibitions/shara-hughesFacebook: www.facebook.com/shara.hughes.7

Instagram: www.instagram.com/sharalynne/?img_index=1

Surreal landscapes and subtly disturbing plants in the enchanted world by Shara Hughes

The need to escape from reality induces some artists to imagine parallel worlds where all has a different dimension, where each thing has an appearance capable of deceiving the eye by its sense of familiarity, but leading a moment later to a completely destabilising configuration compared to what one would expect; in other cases, however, although they refer to something known, this type of creative manages to infuse the artworks with a mysterious aspect, arousing apprehension for the unknown of what within those settings could emerge at any moment. The artist I am going to tell you about today delineates a universe that is strongly connected to the observed, thus showing a possible reality, and then infuses it with a series of multifaceted other options that somehow attract by their aesthetics but at a second glance appear disturbing in some cases, upsetting the first sensation received.

Whenever existential circumstances became intolerable or the result of anxieties and frustrations, certain artists responded by creating a type of painting that was outside the box, unreal, irreverent, subversive at times, precisely in order to confront those external demons, those anxieties to which human beings became accustomed without being able to take their lives into their own hands; at the end of the 15th century, shortly after Europe had emerged from the Middle Ages and began to emerge divisions within the Church, and consequently different ways of dealing with existential and ethical questions, Hieronymus Bosch gave life to an unreal world full of symbols that were intended to be a critique of the rigid religious morality that was still dominant and which only provoked frustrations in man towards drives that continued to exist. With his unreal canvases, linked to the themes of the afterlife, judgement, and sin, such as the painting The Garden of Earthly Delights, and by composing confused landscapes where he hid allegories and subliminal messages of his thought, Bosch became in fact the forerunner of a movement that developed five centuries later, Symbolism, and which had in Odilon Redon one of its most extreme exponents, especially in the figuration of graphic works; floating eyes, eerie flowers, animals with human faces, these were the hallmarks of one of the masters of the movement. Both of these out-of-chorus artistic voices laid the foundations for the next evolution, the one that took shape at the beginning of the 20th century with Surrealism, a current that, following psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud‘s studies on the unconscious, highlighted the oneiric side, the anxieties, the paralysing anguishes within which the mind locked itself, freeing in the sleep phase; Salvador Dali with his world of liquid time, improbable animals, human details hidden in the folds of reality and with the ever-present obsession with sexuality, Max Ernst with his post-apocalyptic landscapes, disturbing decompositions of human parts transformed and then hidden among dense vegetation, the narration of characters on the basis of their most irritating characteristics, were both interpreters of that frightening universe of nightmares that afflicted much of society following the horrors of the First World War, but also of all the most secret and unconfessable drives of man that had to escape and break free.

Surrealism had interesting evolutions towards the end of the 20th century, which on the one hand continued along the more dreamy and fairytale-like vein, as in the case of Vladimir Kush, on the other hand instead, others have turned towards mystery, enigma and the disquieting apparent normality transformed into a distressing option of reality, as in Pop Surrealism. The American artist Shara Hughes draws on the more naturalistic side of Max Ernst to elaborate her style, re-proposing the dense vegetation in the midst of which, however, she does not place pseudo-human figures, nor does she insert symbols, but simply gives a changing, shifting and deceptive point of view that induces the observer to approach by virtue of the harmonious appearance of the narrated settings; but then, once the eye lingers on the details and gets closer to the images, emerges instead an underlying irrelateness, a subtle restlessness through which the inner self lingers on the implications of being inside that fantasy world, on the possibility that not everything may have the pleasant and playful implication evoked at first glance. The flowers look like carnivorous plants, seemingly immobile but ready to take a bite that will then engulf the unfortunate observer, who thus receives a sensation of attraction and immediately afterwards of repulsion; the pictorial style is in some cases close to Surrealism because the definition and description is perfectly real, while in others it shifts towards Expressionism for the chromatic range, for the absence of chiaroscuro and depth, as if the narrative landscape needed to enter an enchanted dimension in order to express the sensations that Shara Hughes wishes to let out.

The choice of tones thus becomes functional not so much to liberate the artist’s interior motions, but rather to lead the observer into the setting most akin to the universe of the journey that is undertaken from time to time and in which the viewer is inevitably involved; the visual deception in fact leads one to believe to be in front of childlike memories, of moments of observation of a natural world waiting to be discovered, with the same wonder of children who can interpret every moment as a marvellous adventure. In Pop, in fact, the details of the stem of the poppy are enlarged in size, as is the flower, almost as if Shara Hughes wanted to narrate a Lilliputian world from which everything seems so giant that it takes on the appearance of a forest, even though it is evidently only a field of flowers; this is the magic game the artist plays in each painting, leading the eye into a once upon a time that seems to be the beginning of a fairy tale and that, like any self-respecting fairy tale, also has the frightening element, the feeling of imminent danger that may come to disturb the protagonist’s path. In Hard hat, the sensation is that of being facing a voracious carnivorous plant, unassailable precisely by virtue of the leathery corollas inside which it could make disappear an insect, an animal or a small man; here the atmosphere is more gloomy, the colour palette is darker and more shadowy, and consequently the overall appearance of the canvas is less deceptively reassuring than in the previous one. Everything seems to be an omen of misfortune, even the sky, in a decidedly expressionist like the background of the landscape, recalls the storm, almost as if to warn of a potential imminent danger; thus the feeling of attraction towards Shara Hughes‘ enchanted environments, in this case becomes a desire to remain outside, to observe the distance instead of immersing oneself in the narrated atmosphere the contrary to what happens in the polyptych The Bridge.

In this artwork made up of four large canvases, the artist describes a landscape that seems to have come straight out of a fantastic tale, where the colours represent the unfolding of the beginning of the story, as if each hue were a word through which the scene manifests itself to the observer; Expressionism is evident in the choice of colours that tend to confuse reality, or perhaps it would be better to say that they go on to generate another reality that is just as possible, where the waters may be sometimes white and sometimes coloured by the setting sun even when they are not directly touched by its rays. The meadows and hills are in turn completely improbable from a colouristic point of view, but in the artist’s pictorial intentions, what is represented is the magic of the sun that can completely change the point of view; as one moves away from its action, however, the landscape becomes dark, enveloped in the shadows of the night that has already arrived, and nature, the flowers themselves, seem to be about to fall asleep waiting for a new day. In the rightmost canvas, even the corollas lose their floral semblance and turn towards greater indefiniteness, seeming to bend or close in on themselves to protect from the cold and the darkness that is about to envelop that fascinating landscape. The alternation between the desire to enter into the narrated scenes and the contrasting tendency to distance oneself from them constitutes the fascination of the paintings of Shara Hughes, an internationally renowned artist who has solo and group exhibitions in important institutional venues all over the world – Denmark, Switzerland, France, USA, China, UK – and her canvases are part of public museum collections in the USA and China.