La maniera di raccontare la realtà davanti ai propri occhi svela l’approccio alla vita di ciascun artista, perché in fondo quello di dipingere è un atto fortemente legato all’interiorità, all’impulso percettivo nei confronti di un’esistenza piena di sfaccettature da interpretare, da assecondare al proprio sentire e alla predisposizione a filtrare le circostanze secondo il singolo punto di vista. Lo stile pittorico che ne deriva diviene dunque manifestazione dell’essenza stessa dell’autore dell’opera, questo sia che ci si trovi davanti a un’opera informale sia che invece il creativo scelga di rimanere più legato alla figurazione. Il protagonista di oggi, oltre a restare fortemente ancorato alla rappresentazione degli scorci che ama, li arricchisce con il filtro della sua sensibilità utilizzando una tecnica in virtù della quale riesce a rarefare le atmosfere raccontate avvolgendole di suggestione.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte l’acquarello è stato a lungo considerato come una tecnica preparatoria alla pittura superiore, una sorta di esercizio, chiamato studio, della realizzazione di alcune parti di quella che avrebbe dovuto essere l’opera principale; Dürer, Pinturicchio, Rubens eseguivano disegni con questa tecnica come prova generale di tutti quei dettagli che poi dovevano essere perfetti una volta tradotti in pittura a olio. Questa limitazione ai disegni preparatori dell’acquarello terminò nel Diciottesimo secolo quando cioè i maggiori maestri dell’epoca ne scoprirono la versatilità e cominciarono a usarlo come stile associabile alla loro figura artistica, in parallelo con la pittura più tradizionale; le atmosfere suggestive di William Turner, massimo rappresentante del Romanticismo Inglese, che amava portare con sé un quaderno su cui immortalare i panorami dei luoghi visitati avvalendosi della fluidità e dell’immediatezza realizzativa dell’acquarello, e poi le ambientazioni visionarie di William Blake, ma soprattutto i paesaggi struggenti di John Robert Cozens, forse il primo vero artista che scelse l’acquarello come unico mezzo espressivo, mostrarono la bellezza e la delicatezza raggiungibile in virtù di questa tecnica. La praticità nel trasporto del blocco da disegno e dei colori ad acqua e la velocità di asciugatura erano ideali durante i viaggi, per immortalare angoli e panorami in maniera estemporanea, ecco perché inizialmente l’acquarello era fortemente legato alla pittura paesaggista; con l’evolversi e l’affermarsi della tecnica, molti artisti che operarono a cavallo tra fine Ottocento e inizi Novecento cominciarono ad applicarlo a soggetti diversi più affini alla loro produzione, come le nature morte nel caso di Paul Cézanne, le ballerine all’interno dei teatri di Edgar Degas, le eleganti donne aristocratiche raccontate da Edouard Manet. Al fascino di questo antico mezzo espressivo rinato a nuova vita non si sottrassero neanche alcuni esponenti dell’Astrattismo come Paul Klee che propose una versione più velata e sussurrata delle sue opere geometriche e contraddistinte da colori caldi; non solo, negli innovativi Stati Uniti, verso la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo, vennero fondate delle società di acquarellisti perché gli artisti aderenti volevano organizzare mostre dedicate solo a quello stile pittorico, che prese piede anche tra creativi la cui principale produzione era legata all’olio. Con Edward Hopper infatti l’acquarello trovò una nuova collocazione paesaggistica, quella appunto legata al suo Realismo Americano fatto di atmosfere sospese e di solitudine malinconica, e un utilizzo diverso, meno diluito con l’acqua e per questo più intenso.

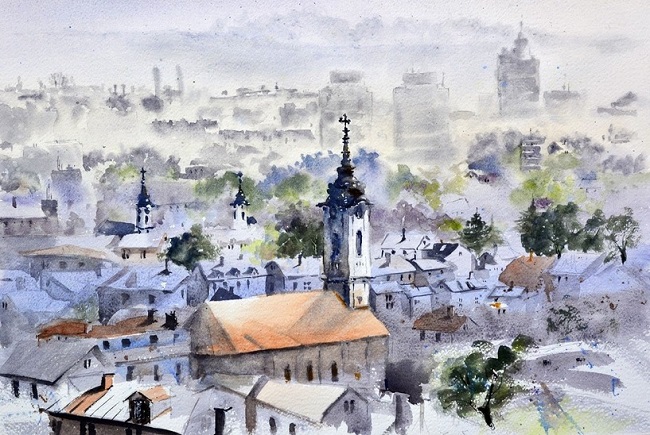

Il maestro serbo Nenad Kojic sceglie l’acquarello come tecnica assoluta, mostrando attraverso la sua capacità espressiva quanta bellezza e fascino siano rivelabili in virtù della possibilità di utilizzare trasparenze, delicatezze cromatiche e un tocco figurativo lieve; il paesaggio è il soggetto più affine alla sua indole di sensibile e appassionato osservatore del mondo che lo circonda, delle città e dei paesi visitati durante i viaggi a cui non riesce a rinunciare, come se essi stessi fossero linfa vitale per una creatività che ha costante bisogno di attingere a riferimenti reali, quegli scorci, quei paesaggi che catturano la sua attenzione e che poi divengono protagonisti delle sue poetiche interpretazioni.

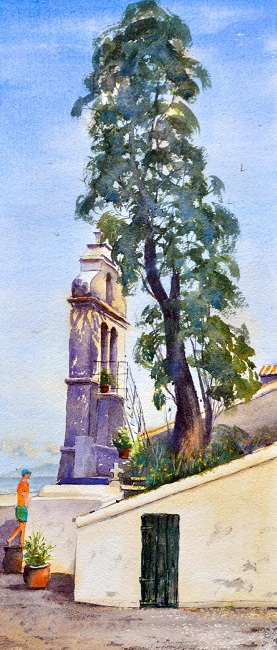

Anche nel suo caso, come già accennato rispetto a Edward Hopper, il colore è utilizzato in modo denso, vibrante, dandogli la consistenza di una tempera e infondendo così ai panorami narrati un aspetto fortemente realistico pur lasciando spazio alle delicate sfumature ottenibili grazie a una sapiente padronanza della tecnica; le opere si permeano dunque di melodia poetica, in alcuni casi palpitano letteralmente attraverso l’alternarsi di luci e ombre, come se Nenad Kojic volesse mettere in evidenza la mobilità costante, il movimento perpetuo della realtà anche laddove il suo sguardo si posa sugli edifici, perché in fondo il solo fatto di essere calati nell’ambiente circostante permette alle energie esterne di interagire con i muri che non sono più inanimati bensì dialogano con le emozioni di chi si sofferma a guardarne la bellezza.

La presenza umana è costantemente presente, a volte palesemente raccontata altre semplicemente intuita, perché Nenad Kojic ama porsi come interprete del suo sentire ma anche di quello di chi si trova all’interno delle scene che desidera immortalare, quasi come se di tutti gli individui ritratti, sebbene lontani e piccoli rispetto alla grandezza degli scenari in cui li colloca, volesse esprimere un frammento di sensazione, il fugace pensiero che ciascuno distrattamente aveva nel momento in cui l’artista si apprestava a dipingere. Ma il protagonista indiscusso degli acquarelli di Kojic è sicuramente il paesaggio, i frammenti colti durante le sue visite nelle città che più ama, Venezia, Praga, Dukbrovnik e ovviamente la sua Belgrado, oltre ad altri luoghi visitati nei suoi spostamenti; i panorami indugiano sulle città perché in fondo è proprio nei centri abitati che si svolge la vita, che l’uomo lascia il segno del suo passaggio con i palazzi, i tetti delle case, i monumenti e tutto ciò che affascina l’artista.

Nell’opera Pedestrian cross on Terazije square Belgrade è evidente la fascinazione ricevuta osservando un luogo familiare ma costantemente mutevole in virtù delle persone che ogni giorno lo attraversano, perdendosi dietro gli impegni quotidiani a causa dei quali non riescono più a vedere la bellezza della piazza su cui si trovano e del palazzo alle sue spalle; questo è forse il motivo per cui Nenad Kojic rende gli individui effimeri attraverso l’esiguità dissolvente delle loro gambe, perché sono lì in quel frangente ma non vi saranno più in un futuro prossimo, mettendo l’accento sulla maestosità della piazza e dell’edificio che sopravvivono nel corso dei secoli apparendo più solidi di qualunque illusione di onnipotenza e di eternità dell’essere umano.

E ancora in Bela ladja na Jadranskom moru Rovinj Hrvatska (Nave bianca sul mare Adriatico, Rovigno) l’artista racconta di un piccolo porto in cui la presenza dell’uomo è marginale, intuita dalla vela, confermata dalle piccole figure appena accennate che camminano sul molo, dalle case sullo sfondo, dalle tende forse di un piccolo ristorante in lontananza; anche in questo acquarello ciò che colpisce l’attenzione dell’artista è la vita urbana nella sua totalità, l’atmosfera che si respira nella località balneare della Croazia in cui il tempo sembra rallentato e la solarità positiva dello scorrere della vita si armonizzano con l’approccio all’esistenza di Nenad Kojic. Il disegno è la base pittorica imprescindibile da cui parte tutto il resto, è solo attraverso la definizione grafica delle ambientazioni scelte che l’artista poi può impreziosire le composizioni pittoriche con le sensazioni percepite a seguito della contemplazione di ciò che ha davanti allo sguardo.

Questo è incredibilmente evidente in Ljubljana in green Slovenia #44 dove la precisione nella descrizione dei palazzi ai lati della stretta via della città fa da struttura alla morbidezza degli alberi sullo sfondo, all’impalpabilità del cielo e al rilassato camminare degli abitanti che sembrano adeguarsi a quella lentezza che ha il sapore della vera vita. Qui le persone sono raccontate in maniera più consistente, quasi come se la loro rilevanza fosse maggiore, sulla base di una maggiore consapevolezza della bellezza in cui vivono rendendoli dunque più presenti perché più predisposti cogliere il momento presente.

Nenad Kojic, formatosi da autodidatta, coltiva il suo talento in maniera amatoriale fino al momento in cui termina il suo percorso professionale, dedicandosi completamente all’arte; da quel momento in avanti ha avuto modo di esporre i suoi lavori ricevendo numerosi premi internazionali e diventando uno dei maggiori maestri di acquarello della Serbia. Le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private in Canada, Stati Uniti, Russia, Giappone, Australia, Turchia e in quasi tutti i paesi europei.

NENAD KOJIC-CONTATTI

Email: nenad.kojic@hotmail.com

Sito web: https://nenad-kojic.pixels.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nenad.kojic

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/akvareli_beograda/

The vibrant and romantic views of Nenad Kojic, when watercolour becomes a poetic interpretation of the observed

The way of recounting reality before one’s eyes reveals each artist’s approach to life, because after all, painting is an act strongly linked to one’s interiority, to the perceptive impulse towards an existence full of facets to be interpreted, to be indulged in according to one’s own feeling and predisposition to filter circumstances according to one’s individual point of view. The resulting pictorial style thus becomes a manifestation of the very essence of the author of the artwork, whether one is in front of an informal work or whether the creative artist chooses to remain more tied to figuration. Today’s protagonist, in addition to remaining strongly anchored to the representation of the views he loves, enriches them with the filter of his sensitivity, using a technique by virtue of which he succeeds in rarefying the atmospheres told by enveloping them in suggestion.

Throughout the history of art, watercolour has long been considered as a preparatory technique for superior painting, a sort of exercise, called a studio, for the realisation of certain parts of what should have been the main artwork; Dürer, Pinturicchio, Rubens made drawings with this technique as a dress rehearsal for all those details that then had to be perfect once they were translated into oil paint. This limitation to preparatory drawings in watercolour ended in the 18th century when the greatest masters of the time discovered its versatility and began to use it as a style they could associate with their art, in parallel with more traditional painting; the evocative atmospheres of William Turner, the greatest representative of English Romanticism, who loved to carry a notebook on which to immortalise the panoramas of the places he visited using the fluidity and immediacy of watercolour, and then the visionary settings of William Blake, but above all the poignant landscapes of John Robert Cozens, perhaps the first true artist to choose watercolour as his sole means of expression, showed the beauty and delicacy that could be achieved by virtue of this technique.

The practicality of transporting drawing pads and watercolours and the speed of drying were ideal when travelling, to immortalise angles and panoramas in an extemporary manner, which is why watercolour painting was initially strongly linked to landscape painting; with the evolution and affirmation of the technique, many artists who worked at the turn of the 19th and early 20th century began to apply it to different subjects more akin to their own production, such as still lifes in the case of Paul Cézanne, dancers in the theatres of Edgar Degas, elegant aristocratic women as depicted by Edouard Manet. Not even some of the exponents of Abstractionism, such as Paul Klee, who proposed a more veiled and whispered version of his geometric works characterised by warm colours, escaped the fascination of this ancient expressive medium reborn to new life. Not only that, in the innovative United States, towards the end of the 19th century, watercolour societies were founded because the participating artists wanted to organise exhibitions dedicated only to that style of painting, which also caught on among creative artists whose main production was linked to oil. With Edward Hopper, in fact, watercolour found a new landscape collocation, the one linked to his American Realism made of suspended atmospheres and melancholic solitude, and a different use, less diluted with water and therefore more intense. The Serbian master Nenad Kojic chooses watercolour as his absolute technique, showing through his expressive capacity how much beauty and charm can be revealed by virtue of the possibility of using transparencies, chromatic delicacy and a light figurative touch; the landscape is the subject most akin to his nature as a sensitive and passionate observer of the world around him, of the cities and towns he has visited during his travels that he cannot renounce, as if they themselves were lifeblood for a creativity that constantly needs to draw on real references, those glimpses, those landscapes that capture his attention and then become the protagonists of his poetic interpretations.

Also in his case, as already mentioned with respect to Edward Hopper, colour is used in a dense, vibrant manner, giving it the consistency of tempera and thus infusing the narrated landscapes with a strongly realistic aspect while leaving room for the delicate nuances that can be obtained thanks to a skilful mastery of technique; the artworks are thus permeated with poetic melody, in some cases literally palpitating through the alternation of light and shadow, as if Nenad Kojic wished to emphasise the constant mobility, the perpetual movement of reality even where his gaze rests on the buildings, because after all, the mere fact of being dropped into the surrounding environment allows external energies to interact with the walls, which are no longer inanimate but dialogue with the emotions of those who pause to gaze upon their beauty. The human presence is constantly present, at times overtly recounted, at others simply intuited, because Nenad Kojic likes to present himself as the interpreter of his own feeling but also of that of those within the scenes he wishes to immortalise, almost as if of all the individuals portrayed, although distant and small compared to the grandeur of the scenarios in which he places them, he wanted to express a fragment of sensation, the fleeting thought that each one distractedly had at the moment when the artist was preparing to paint. But the undisputed protagonist of Kojic‘s watercolours is undoubtedly the landscape, the fragments captured during his visits to the cities he loves most, Venice, Prague, Dukbrovnik and, of course, his own Belgrade, as well as other places he has visited on his travels; the panoramas linger on the cities because after all, it is in the towns that life takes place, that man leaves the mark of his passage with the palaces, the roofs of the houses, the monuments and everything that fascinates the artist.

In the artwork Pedestrian cross on Terazije square Belgrade, the fascination received by observing a place that is familiar but constantly changing by virtue of the people who pass through it every day, losing themselves behind their daily commitments due to which they can no longer see the beauty of the square they are standing on and the building behind it; this is perhaps why Nenad Kojic makes individuals ephemeral through the fading narrowness of their legs, because they are there at that juncture but will no longer be there in the near future, emphasising the majesty of the square and the building that survive over the centuries by appearing more solid than any illusion of omnipotence and eternity of the human being. And again in Bela ladja na Jadranskom moru Rovinj Hrvatska (White Ship on the Adriatic Sea, Rovinj), the artist tells of a small port in which the presence of man is marginal, intuited by the sail, confirmed by the small, barely hinted at figures walking on the pier, the houses in the background, the curtains perhaps of a small restaurant in the distance; also in this watercolour, what strikes the artist’s attention is urban life in its totality, the atmosphere in the Croatian seaside resort where time seems to slow down and the positive sunny flow of life harmonises with Nenad Kojic‘s approach to existence. The drawing is the inescapable pictorial basis from which everything else starts; it is only through the graphic definition of the chosen settings that the artist can then embellish the pictorial compositions with the sensations perceived as a result of contemplating what is in front of his gaze. This is incredibly evident in Ljubljana in green Slovenia #44 where the precision in the description of the buildings on the sides of the narrow city street acts as a structure to the softness of the trees in the background, the impalpability of the sky and the relaxed walking of the inhabitants who seem to adapt to that slowness that has the flavour of real life. Here, the people are portrayed in a more consistent manner, almost as if their relevance were greater, based on a greater awareness of the beauty in which they live, thus making them more present because they are more predisposed to grasp the present moment. A self-taught artist, Nenad Kojic cultivated his talent in an amateur manner until the moment when he ended his professional career, dedicating himself completely to art. From that moment on, he exhibited his work, receiving numerous international awards and becoming one of Serbia’s leading watercolour masters. His artworks are part of private collections in Canada, the USA, Russia, Japan, Australia, Turkey and almost all European countries.