Nella società attuale la tendenza a nascondere la propria vera personalità, l’essenza che in un’altra epoca e in un altro contesto sarebbero liberamente manifestate, induce l’essere umano contemporaneo a sapere di non essere mai completo, di avere delle carenze che scaturiscono esattamente dalla sua incapacità di accettare tutte le sfaccettature di un’interiorità necessitante di essere accolta nella sua interezza. Alcuni artisti mostrano pertanto l’attitudine, oltre che l’incredibile sensibilità, di osservare le persone, di scrutare in profondità i loro occhi e tutto ciò che silenziosamente nascondono, per poter così interpretare, raccontando attraverso la loro arte, tutto quel non detto, tutti i veri colori appartenenti indelebilmente all’anima e che solo attraverso un approccio empatico possono trovare la propria espressione più spontanea. La protagonista di oggi effettua esattamente questo tipo di analisi e di approfondimento degli individui che ruotano intorno alla sua vita, scegliendo pertanto il ritratto come sua caratteristica riconoscitiva pur trasformandolo in qualcosa di nuovo in virtù del forte legame con la natura.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte di ogni tempo, vi sono stati alcuni interpreti che hanno saputo sottolineare con originalità l’esigenza di mostrare con la loro pittura una connessione speciale con l’elemento naturale che abitualmente era solo sfondo, sottofondo secondario alle vicende epiche, o religiose o ai ritratti commissionati da nobili e sovrani. Il primo a rompere gli schemi della figurazione tradizionale, inserendo nei suoi dipinti divenuti celeberrimi e inseguiti dai grandi collezionisti, fu Giuseppe Arcimboldo che sfruttando il fenomeno della pareidolia, a causa del quale lo sguardo tende a riconoscere come umano anche un volto composto con oggetti diversi, diede vita a opere in cui gli ortaggi, i fiori o gli animali abitualmente utilizzati per le nature morte, andavano invece a comporre i volti dei personaggi raffigurati. In qualche modo Arcimboldo nel Cinquecento anticipò la decontestualizzazione morfologica che contraddistinse il lavoro di Hieronymus Bosch, il quale tuttavia si allontanò dall’ironia e dalla natura per soffermarsi sull’inquietante, lo spaventoso e il disturbante in cui trasformava l’aspetto umano con forme animali o appartenenti al mondo della natura per sottolineare l’istinto dell’individuo che tendeva a ribellarsi ai rigidi insegnamenti della religione.

Entrambi i maestri furono precursori delle destabilizzazioni visive utilizzate dagli interpreti del Surrealismo per raccontare quel mondo onirico, legato agli incubi del subconscio attraverso il quale autori come Salvador Dalì, Max Ernst e in un modo più analitico e riflessivo anche René Magritte raccontarono il loro punto di vista sulla natura umana, sulle sue fragilità, sulle paure più inconfessabili e con l’equilibrio con gli istinti e impulsi naturali che tuttavia generavano inquietudini e resistenze nella vita quotidiana. A riprendere, ampliare e personalizzare la tecnica trasformativa di Giuseppe Arcimboldo, è nell’era contemporanea l’artista statunitense Brian Kirhagis che perde l’approccio ironico per entrare in una dimensione più armonica e, sostituendo i frutti con alberi, fiori, fili d’erba e prati, sottolinea la necessità di un ritorno alla natura, di ricostruire un dialogo tra tutto ciò che circonda l’essere umano e che viene ignorato nell’urgenza del vivere in una società dove il rumore e la tecnologia tendono a far dimenticare all’individuo la propria vera essenza. In tutti questi casi l’esigenza creativa è quella di lasciar emergere simbolicamente le caratteristiche interne delle persone, oppure quelle istintive o ancora invece quelle più orientate a connettersi al mondo circostante secondo un approccio più spiritualista e al contempo simbolista. L’artista olandese Angela Maria Sierra, in arte Riso Chan, attinge alle esperienze pittoriche sperimentali del passato per dar vita a opere in cui la natura non è più descrittiva come nel caso di Kirhagis, e neanche simbolo ironico e irriverente delle personalità dei nobili immortalati come nel caso di Arcimboldo, bensì semplicemente una manifestazione esterna tra anima, tra caratteristiche intrinseche dei personaggi raccontati, e quei veri colori che fuoriescono con la stessa delicatezza di un giardino fiorito le cui tonalità si armonizzano con i pensieri, i sentimenti, i ricordi, le emozioni e i desideri segreti troppo spesso nascosti e inconfessati.

Attraverso lo sguardo attento di Riso Chan i suoi protagonisti vengono messi a nudo, osservati in profondità andando oltre la maschera che indossano davanti al mondo e raccontati secondo la loro naturalezza più spontanea, con le foglie, i fiori, gli animali che più si avvicinano alle loro peculiarità caratteriali; dunque in questo caso la natura non va a comporre il volto o l’aspetto esteriore, al contrario diviene emanazione di un sé che sembra più rappresentare l’anima, come se nei ritratti di Riso Chan la vera essenza non potesse fare a meno di emergere, di manifestarsi fino a predominare sull’immagine esterna.

La vicinanza con il mondo che circonda l’essere umano è irrinunciabile per l’autrice perché in fondo nell’espressività più spontanea e immediata ciascun individuo ha fragilità e punti di forza riconducibili proprio agli istinti primordiali così vicini a quelle reazioni istintive di piante e animali. Quella dell’artista è quasi un’esortazione verso l’osservatore a lasciarsi dominare dal vero sé, da quella parte autentica lasciata in silenzio dietro la coltre della quotidianità, costretta a nascondersi per sopravvivere in un mondo contemporaneo che chiede, o forse sarebbe meglio dire esige, di vedere solo la perfezione della patina superficiale senza compiere troppi approfondimenti.

Dal punto di vista esecutivo le sue opere mescolano la tecnica dell’Arte Digitale, attraverso cui elabora i suoi volti fino a sovrapporli a tutti gli elementi naturali che corrispondono alla personalità dei protagonisti, all’acquarello con cui infonde un apporto manuale ma anche fortemente evanescente al risultato finale, sottolineando quanto quell’anima interiore si trovi in un punto a metà tra osservazione e intuizione, tra realtà oggettiva e soggettività che traspare in modo delicato quanto tuttavia fortemente caratterizzante. Il Surrealismo entra proprio in quell’apporto metafisico e simbolista che tende a decontestualizzare sia l’aspetto reale dei personaggi, sia un ambiente circostante che diviene solo e unicamente uno sfondo suggestivo che canalizza l’attenzione sull’immagine in primo piano.

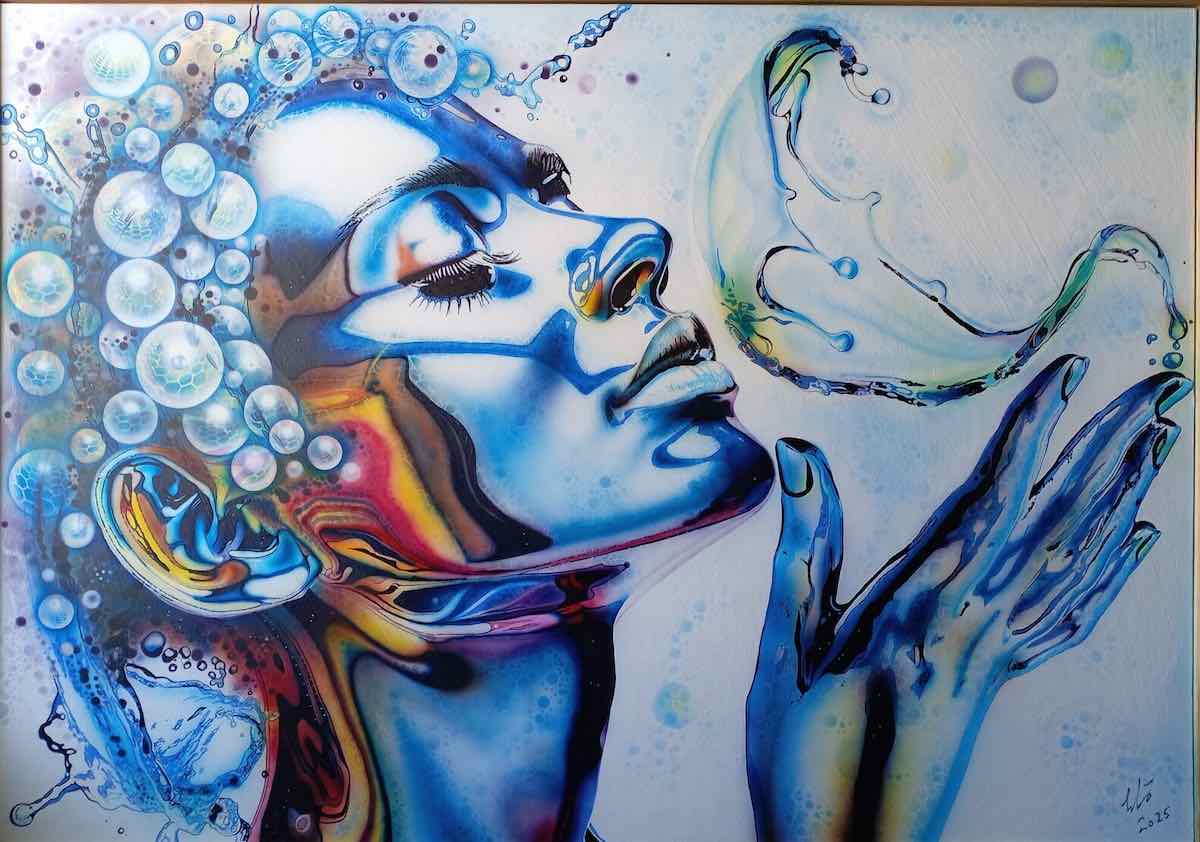

L’opera Freedom racconta di un desiderio inconfessato di affrancamento da tutte le gabbie che sembrano trattenere l’anima della ragazza, quasi come se la sua interiorità desiderasse librarsi in volo e allontanarsi da tutto ciò che la tiene saldamente a terra; l’azzurro e il celeste che predominano cromaticamente si vanno a legare agli uccelli che compongono il volto della donna, unendo così il cielo, che è il regno del volo, al sogno intimista e al mondo del desiderio, che è appunto quello di permettere alla sua essenza di fluire e determinare le scelte future.

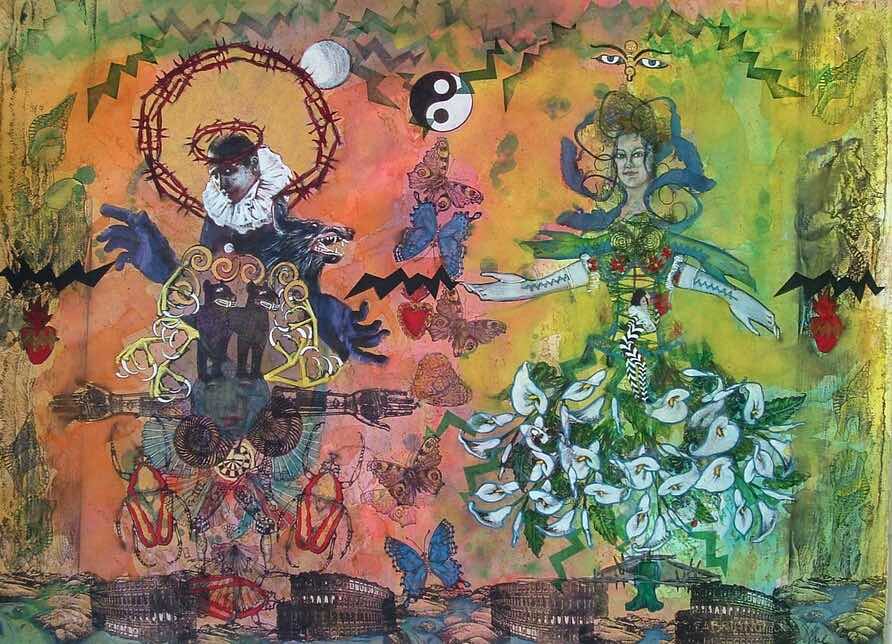

In I’m a kid and a man Riso Chan sottolinea quella tendenza a nascondere il bambino interiore dentro l’adulto, sebbene il primo non riesca completamente a essere oscurato dal secondo perché in fondo è quello che sa divertirsi, ridere a crepapelle, apprezzare anche i momenti più apparentemente insignificanti e non funzionali al raggiungimento di uno scopo o di un fine logico e forse proprio per questo pieni di intensità emotiva. In questa opera a predominare in maniera assoluta sono le differenti sfaccettature cromatiche, più equilibrate e fredde quelle legate al lato uomo, mentre più vivaci, calde, contraddistinte dalla stilizzazione dei fiori quasi accennati e impercettibili quelle riferite alla parte fanciullesca; nello sguardo del personaggio ritratto emerge in modo chiaro la perplessità dovuta alla consapevolezza di dover sostenere un dualismo che da un lato lo fa sentire privilegiato, dall’altro quasi destabilizzato dalla consapevolezza di dover convivere con le sue differenti e opposte parti di sé.

Fragile è emblematica della personalità femminile in generale, e della ragazza protagonista in particolare, che spesso ha al suo interno debolezze e una delicatezza talmente spiccate da poter essere ferite persino senza che la persona con cui si interfaccia ne sia consapevole, perché una farfalla con la sua bellezza impalpabile non può essere spiegata, semplicemente deve essere intuita con apertura empatica. Dunque la richiesta silenziosa espressa dallo sguardo, è di non ferire quell’intensa e profonda emotività, di non toccare le ali di quella farfalla che appartiene alla sua natura per evitare di farle perdere la polvere magica che le permette di volare; il prato fiorito che contraddistingue i capelli e il mezzobusto della donna sembrano essere uno scrigno protettivo avvolgente e colorato attraverso cui lasciar fuoriuscire le sensazioni più pure e positive.

Riso Chan, artista e insegnante creativa con sede ad Amsterdam, ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a esposizioni collettive internazionali in Cina, Stati Uniti, Paesi Bassi ed Estonia.

RISO CHAN-CONTATTI

Email: hello@risochan.com

Sito web: www.risochan.com/

Instagram: www.instagram.com/risochan/

The inner worlds by Riso Chan, between Expressionism and Surrealism to free the true nature of the individual

In today’s society, the tendency to hide one’s true personality, the essence that in another era and context would be freely manifested, leads the contemporary human being to know that he is never complete, that he has shortcomings that stem precisely from his inability to accept all the facets of an interiority that needs to be accepted in its entirety. Some artists therefore show the aptitude, as well as the incredible sensitivity, of observing people, of deeply scrutinising their eyes and all that they silently conceal, in order to be able to interpret, by telling through their art, all that is unspoken, all the true colours that belong indelibly to the soul and that can only find their most spontaneous expression through an empathic approach. Today’s protagonist carries out exactly this type of analysis and in-depth examination of the individuals that revolve around her life, thus choosing the portrait as her recognisable characteristic while transforming it into something new by virtue of the strong bond with nature.

Throughout the history of art of all times, there have been certain interpreters who have been able to emphasise with originality the need to show with their painting a special connection with the natural element that was usually only a background, a secondary backcloth to epic or religious events or to portraits commissioned by nobles and sovereigns. The first to break the mould of traditional figuration, including in his paintings that became famous and sought after by great collectors, was Giuseppe Arcimboldo who, exploiting the phenomenon of pareidolia, due to which the eye tends to recognise as human even a face composed of different objects, created works in which the vegetables, flowers or animals usually used for still lifes, went instead to compose the faces of the personages depicted. In some ways Arcimboldo in the 16th century anticipated the morphological decontextualisation that characterised the work of Hieronymus Bosch, who, however, moved away from irony and nature to dwell on the disquieting, the frightening and the disturbing in which he transformed the human aspect with animal forms or belonging to the world of nature in order to emphasise the instinct of the individual who tended to rebel against the rigid teachings of religion.

Both masters were forerunners of the visual destabilisations used by the interpreters of Surrealism to narrate that oneiric world, linked to the nightmares of the subconscious through which authors such as Salvador Dalì, Max Ernst and in a more analytical and reflective way also René Magritte recounted their views on human nature, its fragilities, its most unconfessable fears and the balance with natural instincts and impulses that nevertheless generated disquiet and resistance in everyday life. To take up, extend and personalise Giuseppe Arcimboldo‘s transformative technique, it is in the contemporary era the American artist Brian Kirhagis who loses the ironic approach to enter a more harmonic dimension and, by replacing fruit with trees, flowers, blades of grass and meadows, emphasises the need for a return to nature, to reconstruct a dialogue between everything that surrounds the human being and that is ignored in the urgency of living in a society where noise and technology tend to make the individual forget his own true essence. In all these cases, the creative need is to allow the inner characteristics of people to emerge symbolically, or those that are instinctive, or those that are more oriented towards connecting with the surrounding world according to a more spiritualist yet symbolist approach.

The Dutch artist Angela Maria Sierra, aka Riso Chan, draws on the experimental pictorial experiences of the past to create works in which nature is no longer descriptive as in the case of Kirhagis, nor even an ironic and irreverent symbol of the personalities of the immortalised noblemen as in the case of Arcimboldo, but simply an external manifestation between the soul, between the intrinsic characteristics of the characters portrayed, and those true colours that emerge with the same delicacy as a flower garden whose tones harmonise with the thoughts, feelings, memories, emotions and secret desires too often hidden and unconfessed. Through Riso Chan‘s attentive gaze her protagonists are laid bare, observed in depth, going beyond the mask they wear in front of the world and told in their most spontaneous naturalness, with the leaves, flowers and animals that come closest to their character traits; so in this case nature does not go to make up the face or the external appearance, on the contrary it becomes an emanation of a self that seems more to represent the soul, as if in Riso Chan‘s portraits the true essence cannot help but emerge, to manifest itself to the point of predominating over the external image.

The closeness with the world that surrounds the human being is inalienable for the artist because, after all, in the most spontaneous and immediate expressiveness, each individual has fragilities and strengths that can be traced back precisely to the primordial instincts so close to those impulsive reactions of plants and animals. That of the artist is almost an exhortation to the observer to let himself be dominated by his true self, by that authentic part left in silence behind the blanket of everyday life, forced to hide in order to survive in a contemporary world that asks, or perhaps it would be better to say demands, to see only the perfection of the superficial patina without going into too much detail. From an executive point of view, her artworks mix the technique of Digital Art, through which she elaborates her faces until they are superimposed on all the natural elements that correspond to the personality of the protagonists, to the watercolour with which she infuses a manual but also strongly evanescent contribution to the final result, emphasising how that inner soul lies somewhere between observation and intuition, between objective reality and subjectivity that transpires in a delicate yet strongly characterising manner. Surrealism enters precisely into that metaphysical and symbolist contribution that tends to decontextualise both the real appearance of the characters and a surrounding environment that becomes solely and only a suggestive background that channels attention to the foreground image.

The artwork Freedom tells of an unconfessed desire to break free from all the cages that seem to hold the girl’s soul, almost as if her interiority wished to soar and distance itself from all that keeps it firmly on the ground; the blue and light blue that predominate chromatically tie in with the birds that make up the woman’s face, thus uniting the sky, which is the realm of flight, with the intimist dream and the world of desire, which is precisely that of allowing her essence to flow and determine her future choices. In I’m a kid and a man, Riso Chan emphasises that tendency to hide the inner child within the adult, even though the former cannot be completely overshadowed by the latter because after all is the one who knows how to have fun, to laugh out loud, to appreciate even the most apparently insignificant moments that do not serve a purpose or a logical aim and perhaps for this very reason are full of emotional intensity.

In this work, the different chromatic facets predominate in an absolute manner: those related to the adult side are more balanced and cold, while those related to the childlike one are livelier, warmer, distinguished by the stylisation of the almost hinted at and imperceptible flowers; in the gaze of the character portrayed, the perplexity due to the awareness of having to sustain a dualism that on the one hand makes him feel privileged, and on the other almost destabilised by the awareness of having to live with his different and opposing parts of himself emerges clearly. Fragile is emblematic of the female personality in general, and of the girl protagonist in particular, who often has such weaknesses and delicacy within her that she can even be wounded without the person with whom she interfaces being aware of it, because a butterfly with its impalpable beauty cannot be explained, it simply has to be intuited with empathic openness. So the silent request expressed by the gaze, is not to hurt that intense and profound emotionality, not to touch the wings of that butterfly that belongs to her nature to avoid making her lose the magic dust that allows her to fly; the flowery meadow that distinguishes the woman’s hair and half-bust seem to be a protective enveloping and colourful casket through which the purest and most positive sensations can escape. Riso Chan, an artist and creative teacher based in Amsterdam, has participated in international group exhibitions in China, the USA, the Netherlands and Estonia.