Spesso la fantasia immaginativa di un artista ha bisogno di entrare in quella terra di mezzo tra realtà e sogno, tra atmosfere che innegabilmente appartengono a ciò che lo sguardo conosce e la capacità di tratteggiare un universo fantastico all’interno del quale tutto assume un significato più ovattato, più soffice proprio perché si lega al desiderio di un mondo migliore, più puro e meno pragmatico di quello attuale. In questo tipo di approccio pittorico ogni dettaglio può trasformarsi in simbolo funzionale a permettere di comprendere, o riflettere, sul messaggio che l’autore desidera imprimere sulla tela, divenendo interprete del sentire dei suoi soggetti ma anche di quel nascosto che può svelarsi solo in virtù di una forte capacità empatica e di una particolare sensibilità. Šárka El ridisegna i confini dello stile a cui in maniera quasi innata sceglie di appartenere, trasformandoli in magia narrativa dentro la quale non si può fare a meno di lasciarsi cullare.

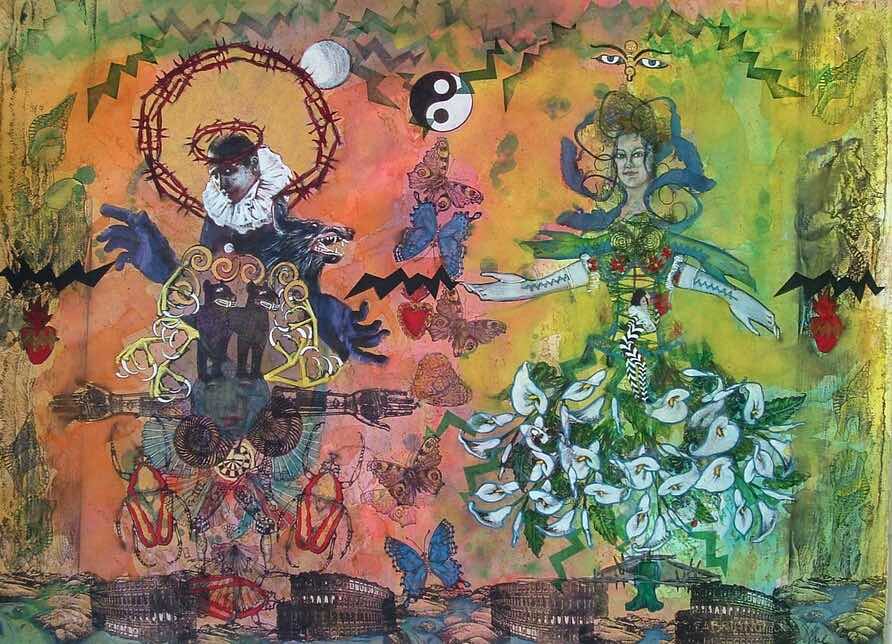

Tra la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo e gli inizi del Ventesimo, cominciò a delinearsi in alcuni artisti l’esigenza di andare a indagare tutto il non detto, il non percepito, l’aura incantata che spesso ammanta la realtà senza che l’essere umano sia in grado di scorgerla, questo oggi tanto quanto ieri; a partire dal Simbolismo di fine Ottocento fu chiaro che quelle energie sottili avevano bisogno di essere indagate, di emergere dal silenzio per trovare una voce espressiva che potesse mostrare la correlazione tra interiorità umana e le forze soprannaturali, o forse sarebbe meglio dire spirituali, che si nascondevano nella natura. L’attitudine a trasformare l’arte da osservazione oggettiva a emanazione soggettiva, interpretata secondo la sensibilità e le caratteristiche di ciascun autore, contraddistinse l’opera di Odilon Redon, di Gaston Bussière e di Arnold Böcklin, solo per citare i più rappresentativi, e aprì le porte all’indagine sull’inconosciuto che fu successivamente ripresa e approfondita dai movimenti del Novecento. Il Surrealismo, nella sua accezione più Metafisica dei belgi René Magritte e di Paul Delvaux, volle mettere in luce non solo il mondo onirico bensì anche il sottile mistero, l’enigma che contraddistingueva la quotidianità e che aveva solo bisogno di essere evidenziato per diventare un altro punto di vista sull’osservato, rivelando quei dubbi o fantasmi della mente a cui era difficile dare un senso se non attraverso la pittura. Il Realismo Magico concentrò la sua attenzione su tutto il non detto, sugli sguardi indecifrabili dei protagonisti delle tele di Felice Casorati e di Antonio Donghi, il quale quest’ultimo introdusse la magia del circo equestre all’interno di molte opere, quasi a voler sottolineare quanto la magia fosse sempre stata a un passo dall’individuo. Ma anche una parte dell’Art Nouveau, e più precisamente quella che andò a costituire a Vienna il movimento del Secessionismo, ebbe tra i suoi maggiori esponenti, nonché fondatore, Gustav Klimt una figura pittorica poliedrica riconducibile a sua volta all’impalpabilità del Simbolismo, soprattutto per le atmosfere di cui avvolgeva i suoi personaggi, sia nel caso in cui doveva esaltare la figura femminile, sia quando raccontava di amanti, di sentimenti troppo forti e intensi per essere raccontati in modo nitido. Nel caso di alcune delle tele più famose dell’autore austriaco, l’introduzione della decontestualizzazione degli sfondi e l’utilizzo generoso della foglia oro contribuirono a infondere nell’osservatore la sensazione di trovarsi elevato dalla realtà e immerso in una dimensione ideale dove tutte le emozioni erano esaltate e poeticizzate proprio in virtù della delicatezza realizzativa e di quell’ascolto verso le energie sottili e misteriose che circondavano la vita. Sebbene con un approccio molto più esistenzialista e formalmente meno soffuso, anche il Realismo Americano di Edward Hopper voleva tendere verso l’interpretazione di tutte quelle considerazioni, pensieri e stati d’animo dell’essere umano della società statunitense di quel periodo, mettendo in relazione l’ambiente esterno con il sentire interiore.

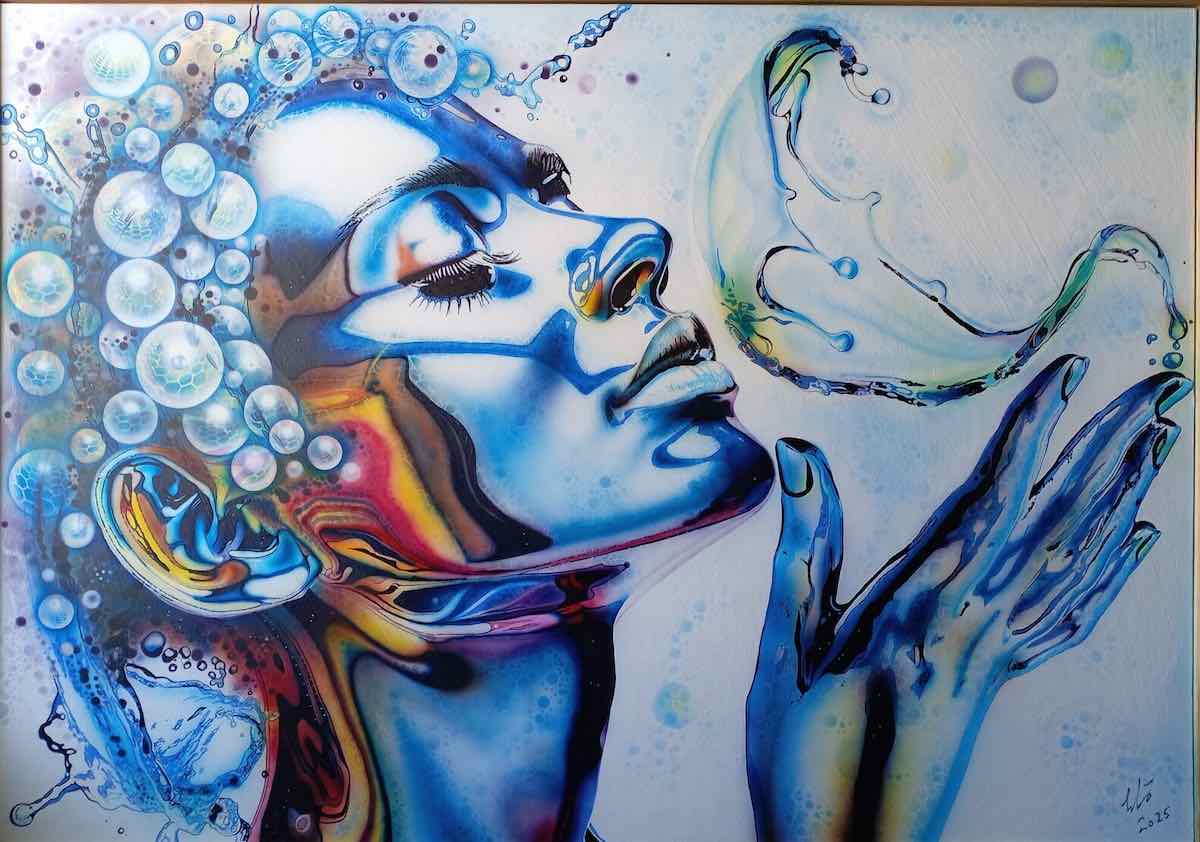

L’artista ceca Šárka Ledová, in arte Šárka El, attinge alle esperienze simboliste mescolandole con l’impalpabilità della Secessione Viennese di Gustav Klimt per dar vita a uno stile personale in cui svela la sua sensibilità, la capacità di cogliere la morbidezza e la soavità che si nasconde dietro espressioni o pose del corpo con cui ritrae le sue protagoniste, essenzialmente donne; in lei tuttavia spesso entra in gioco anche la dissolvenza dell’Astrattismo, come se quest’ultimo fosse funzionale a mettere in risalto gli sguardi, i pensieri, le emozioni che legano indissolubilmente la natura e l’essere umano. La presenza dei piccoli animali delicati con cui Šárka El contorna le sue figure femminili come a metterle in dialogo con essi, costituisce infatti un legame simbolico poiché le farfalle, gli uccellini, i gatti, costituiscono l’elemento incantato di legame con i desideri delle protagoniste, con la loro indole più autentica e con le loro personalità.

La morbidezza cromatica in cui spesso entra in gioco la foglia oro contribuisce a enfatizzare la poeticità delle ambientazioni, come fossero sospese nel sogno più avvolgente, quello più etereo e tratteggiato per cullare l’emotività e la sensazione che quei mondi immaginati dall’autrice siano sottilmente possibili se si è capaci di far parlare l’anima. I dipinti di Šárka El conducono dunque nell’universo della semplicità, dell’immediatezza, delle atmosfere in cui il fanciullo si immerge quando non ha ancora affrontato le difficoltà e gli ostacoli della realtà, e che l’adulto dimentica fino al momento in cui non si trova davanti a un’immagine che va a sollecitare proprio quell’ingenuità e spontaneità perdute nel percorso di crescita.

L’opera Con una valigia piena di stelle incarna perfettamente questo concetto poiché la bambina di spalle guarda con speranza verso il futuro il cui sfondo è indefinito, astratto, decontestualizzato perché non è possibile conoscere ciò che accadrà dopo, l’unica cosa che è possibile fare è sognare e affrontare le circostanze che verranno con fiducia e positività. Il gatto, compagno della giovane, simboleggia l’istinto, l’indipendenza ma anche il legame affettivo profondo che cura silenziosamente ma con una presenza costante, scegliendo di non lasciarla sola nel suo prossimo cammino. Malgrado il volto della bambina non si veda, si intuisce attraverso la posa del suo corpo sia l’esitazione per non sapere ciò che la aspetterà oltre quella cortina di foglia oro che l’ha protetta finora e sia l’aspettativa di un domani radioso e pieno di bellezza; che questo si realizzi o meno dipende solo dall’atteggiamento che saprà assumere e mantenere davanti agli inevitabili ostacoli che si presenteranno.

In Sorellanza Šárka El mostra quanto il Secessionismo influenzi la sua pittura perché qui i volti definiti e fortemente espressivi, quasi le due donne volessero proteggersi vicendevolmente dal mondo esterno, sono circondati dalla sofficità di uno sfondo che prende il sopravvento per avvolgere il sentimento intenso e inscindibile che lega le sorelle. Il bianco e nero dei ritratti viene pertanto esaltato dall’utilizzo della foglia oro con cui l’autrice impreziosisce tutto quello scrigno di ricordi, di condivisioni, di segreti e di solidarietà che appartiene alle figure femminili protagoniste dell’opera e che viene reso concreto e solido in virtù dei rilievi quasi graffiati che entrano e si insinuano sopra il tratto grafico con cui vengono narrati i volti in primo piano.

Anche nel dipinto In un’ondata di fiori è evidente il tema Art Nouveau con forte accezione simbolista poiché la donna sembra quasi sparire all’interno di quell’esplosione di natura, come se in qualche modo le sue emozioni prendessero il sopravvento facendola sentire sopraffatta; la purezza dei sentimenti viene esaltata mostrandone tutta la preziosità, e al contempo l’impalpabilità perché a volte è impossibile comprende e afferrare la cascata di pensieri e di sensazioni che avvolgono la mente e l’interiorità al punto di rendere impossibile l’intervento della logica e della razionalità. L’espressione della ragazza, che fa capolino tra i petali dei fiori, racconta esattamente di quell’istante in cui la ragione viene messa in silenzio dall’irrazionalità di un istinto in grado di essere guida e protezione.

Colibrì innamorati è un’opera più sperimentale dal punto di vista esecutivo poiché Šárka El introduce elementi materici come il gesso e le perline con cui completa la raffigurazione di uno dei simboli della bellezza di ogni tempo, Marilyn Monroe, circondata da uno sfondo astratto, quasi a indicare che pur essendo rimasta nel mito non appartiene più a questa terra, mentre intorno a lei volano dei piccoli e leggerissimi colibrì che simboleggiano da un lato l’effervescenza con cui la grande diva degli anni Cinquanta nascondeva la profondità della sua anima, dall’altro la purezza di un’interiorità che non è stata capita né considerata perché ciò che veniva messo in evidenza era solo e unicamente la bellezza esteriore. I colibrì invece, come suggerito dal titolo, si innamorano proprio di quell’essenza ben nascosta e svelata solo dall’intensità del suo sguardo.

Šárka El, che nel periodo più recente si sta misurando anche con il disegno a carboncino e a matita mescolandolo all’irrinunciabile acrilico, partecipa regolarmente a mostre collettive nella Repubblica Ceca e all’estero, riscuotendo consensi sia dagli addetti ai lavori che dal pubblico.

ŠÁRKA EL-CONTATTI

Email: sarky@centrum.cz

Facebook: www.facebook.com/sarkyeis

Instagram: www.instagram.com/sarka_el_art/

The delicacy of Symbolist Realism by Šárka El, when impalpability meets poetry

Often, an artist’s imaginative fantasy needs to enter that middle ground between reality and dream, between atmospheres that undeniably belong to what the eye knows and the ability to sketch a fantastic universe in which everything takes on a more muffled, softer meaning precisely because it is linked to the desire for a better, purer, and less pragmatic world than the current one. In this type of pictorial approach, every detail can be transformed into a functional symbol that allows to understand or reflect on the message that the author wishes to imprint on the canvas, becoming an interpreter of the feelings of his subjects but also of that hidden which can only be revealed by virtue of a strong capacity of empathy and a particular sensitivity. Šárka El redraws the boundaries of the style to which she almost innately chooses to belong, transforming them into narrative magic that one cannot help but be lulled by.

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, some artists began to feel the need to investigate everything that was unsaid, unperceived, the enchanted aura that often shrouds reality without human beings being able to see it, today as much as yesterday; starting with Symbolism in the late 19th century, it became clear that these subtle energies needed to be investigated, to emerge from silence and find an expressive voice that could reveal the correlation between human interiority and the supernatural, or perhaps it would be better to say spiritual, forces hidden in nature. The ability to transform art from objective observation to subjective emanation, interpreted according to the sensitivity and characteristics of each author, distinguished the work of Odilon Redon, Gaston Bussière, and Arnold Böcklin, to name only the most representative, and opened the door to the investigation of the unknown, which was subsequently taken up and explored in greater depth by the movements of the 20th century.

Surrealism, in its most Metaphysical sense as interpreted by the Belgians René Magritte and Paul Delvaux, sought to highlight not only the dream world but also the subtle mystery, the enigma that characterized everyday life and that only needed to be highlighted to become another point of view on the observed, revealing those doubts or ghosts of the mind that were difficult to make sense of except through painting. Magical Realism focused its attention on everything left unsaid, on the indecipherable gazes of the protagonists of Felice Casorati and Antonio Donghi‘s paintings, who the latter introduced the magic of the circus into many of his artworks, as if to emphasize how magic had always been just a step away from the individual.

But even part of Art Nouveau, and more precisely the movement that formed the Secessionism in Vienna, had among its leading exponents as well as its founder, Gustav Klimt, a multifaceted painter who can in turn be traced back to the intangibility of Symbolism, especially for the atmospheres he enveloped his characters in, both when he wanted to exalt the female figure and when he told stories of lovers and feelings too strong and intense to be recounted clearly. In the case of some of the Austrian artist’s most famous paintings, the introduction of decontextualized backgrounds and the generous use of gold leaf helped to instill in the observer the feeling of being elevated from reality and immersed in an ideal dimension where all emotions were exalted and poeticized precisely because of the delicacy of the execution and that listening to the subtle and mysterious energies that surrounded life. Although with a much more existentialist and formally less suffused approach, Edward Hopper‘s American Realism also sought to interpret all the considerations, thoughts, and moods of human beings in American society at that time, relating the external environment to inner feelings.

Czech artist Šárka Ledová, aka Šárka El, draws on symbolist experiences, mixing them with the intangibility of Gustav Klimt‘s Viennese Secession to create a personal style in which she reveals her sensitivity, her ability to capture the softness and gentleness hidden behind the expressions or poses of the bodies with which she portrays her subjects, essentially women; in her, however, often comes into play the fading of Abstract Art as if it served to highlight the looks, thoughts, and emotions that inextricably link nature and human beings. The presence of small, delicate animals with which Šárka El surrounds her female figures, as if to put them in dialogue with them, constitutes a symbolic link, since butterflies, birds, and cats are the enchanted element that connects the protagonists’ desires, their most authentic nature, and their personalities. The soft colors, often enhanced by gold leaf, emphasize the poetic nature of the settings, as if they were suspended in the most enveloping dream, the most ethereal and sketchy, to lull the emotions and the feeling that the worlds imagined by the artist are subtly possible if one is able to let the soul speak. Šárka El‘s paintings thus lead into a universe of simplicity, immediacy, and atmospheres in which children immerse themselves when they have not yet faced the difficulties and obstacles of reality, and which adults forget until they are confronted with an image that stimulates the very naivety and spontaneity lost in the process of growing up.

The work With a Suitcase Full of Stars perfectly embodies this concept, as the little girl, seen from behind, looks hopefully towards a future whose background is undefined, abstract, and decontextualized because it is impossible to know what will happen next, the only thing possible is to dream and face the circumstances that will come with confidence and positivity. The cat, the young girl’s companion, symbolizes instinct and independence, but also the deep emotional bond that heals silently but with a constant presence, choosing not to leave her alone on her next journey. Although the girl’s face cannot be seen, her body language conveys both her hesitation at not knowing what awaits her beyond the curtain of gold leaf that has protected her until now, and her expectation of a bright and beautiful tomorrow; whether this comes to pass or not depends solely on the attitude she adopts and maintains in the face of the inevitable obstacles that will arise. In Sisterhood, Šárka El shows how much Secessionism influences her painting because here the defined and highly expressive faces, as if the two women wanted to protect each other from the outside world, are surrounded by the softness of a background that takes over to envelop the intense and inseparable feeling that binds the sisters.

The black and white of the portraits is therefore enhanced by the use of gold leaf, with which the artist embellishes the treasure chest of memories, shared experiences, secrets, and solidarity that belongs to the female figures who are the protagonists of the work. This is made concrete and solid by the almost scratched reliefs that enter and creep over the graphic lines with which the faces in the foreground are narrated. The Art Nouveau theme is also evident in the painting In a Wave of Flowers, with a strong symbolist connotation, as the woman seems to almost disappear within that explosion of nature, as if her emotions were somehow taking over, making her feel overwhelmed; the purity of feelings is exalted, revealing all their preciousness and, at the same time, their intangibility, because sometimes it is impossible to understand and grasp the cascade of thoughts and sensations that envelop the mind and inner self to the point of rendering impossible logic and rationality.

The expression of the girl, peeking out from among the petals of the flowers, tells exactly of that moment when reason is silenced by the irrationality of an instinct capable of being a guide and protection. Hummingbirds in Love is a more experimental painting from an executive point of view, as Šárka El introduces material elements such as plaster and beads to complete the depiction of one of the symbols of timeless beauty, Marilyn Monroe, surrounded by an abstract background, as if to indicate that, despite remaining a myth she no longer belongs to this earth, while small, light hummingbirds fly around her, symbolizing on the one hand the effervescence with which the great diva of the 1950s hid the depth of her soul, and on the other the purity of an inner life that was neither understood nor considered because what was highlighted was solely and exclusively her external beauty. Instead hummingbirds, as suggested by the title, fall in love with that well-hidden essence, revealed only by the intensity of her gaze. Šárka El, who has recently been experimenting with charcoal and pencil drawing mixed with the indispensable acrylic, regularly participates in group exhibitions in the Czech Republic and abroad, receiving acclaim from both professionals and the public.