Molto spesso gli artisti scoprono il loro talento naturale in maniera insolita, a volte dopo un percorso lungo e tortuoso che li induce ad avvertire l’esigenza di manifestare la propria interiorità attraverso il contatto con la tela e i colori, in altri casi invece pur essendo la consapevolezza dell’indole creativa chiaramente manifesta da molto tempo, si giunge a una rivelazione che spesso stravolge le convinzioni precedenti e permette di tendere verso un’evoluzione inaspettata la quale diviene il centro della ricerca artistica, e forse anche il suo compimento. Questo è stato il caso della protagonista di oggi che ha modificato l’essenza del suo dipingere da espressione del sé ad ascolto totale delle pietre le quali sembrano suggerirle la loro essenza più profonda che lei poi interpreta svelandole all’osservatore.

Il rapporto primordiale dell’artista con la roccia risale a epoche lontane, preistoriche, poiché la tendenza a imprimere la propria creatività ha sempre appartenuto all’essere umano, anche laddove la razionalità e la conoscenza non appartenevano a una condizione di vita in cui l’istinto predominava su tutto; è stato esattamente grazie a quei segni, i graffiti, lasciati all’interno delle caverne che è stato possibile ricostruire frangenti di quel lontano periodo scoprendo abitudini, usi e costumi di popolazioni distanti secoli eppure capaci, in modo rudimentale, di fare arte. Nell’evolversi dell’umanità è stata sempre la pietra naturale, compreso dunque il marmo, a essere protagonista principale della manifestazione del talento di grandi scultori che erano chiamati a effigiare le tombe o rendere omaggio ai faraoni, nell’antico Egitto, o a raccontare le gesta degli eroi e le loro qualità morali, nella Grecia antica che diede la culla a grandi autori come Fidia e Policleto; in entrambe le grandi civiltà la pietra era utilizzata per lasciare messaggi chiari e inequivocabili alle popolazioni, così come per testimoniare l’influenza del divino e della spiritualità nella quotidianità. Era elemento fondamentale ed eterno per elevare la coscienza del popolo e per permettere a tutti, malgrado l’elevato analfabetismo poiché a pochi era consentito di studiare, di comprendere gli insegnamenti delle religioni politeiste che incidevano e predominavano nella società.

Oltrepassato il Classicismo e avanzando nei secoli furono molti gli scultori che lasciarono grandi testimonianze del loro talento esaltando la capacità comunicativa della pietra naturale, concretizzando e affermando in maniera via via più evidente l’importanta dell’arte che comprendeva ormai anche la pittura. Dal Rinascimento fino all’epoca contemporanea si è assistito a un’integrazione della scultura nell’architettura, ma soprattutto alla rappresentazione delle differenti epoche e anche dei linguaggi stilistici che inizialmente si legavano a una figurazione tradizionale, mescolandosi spesso con insegnamenti religiosi o rappresentando iconografie cristiane, e poi lentamente evolsero fino ad adeguarsi ai cambiamenti epocali del Novecento dove il marmo e la pietra assunsero le forme indefinite tipiche dell’Arte Informale e Astratta. Donatello, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Antonio Canova furono maestri nel modellare il duro marmo rendendolo talmente uguale alla figura umana da togliere il fiato, tanto quanto Auguste Rodin infuse di emozionalità e di pathos le sue opere scultoree dove il materiale diveniva un mezzo per evidenziare il suo approccio esistenzialista all’arte. La pietra è stata fondamentale anche nel percorso dadaista-surrealista di Jean Arp, in cui la rinuncia alla forma era funzionale a esaltare il concetto e il tema narrato, sensuale o in alcuni casi enigmatico nella sua pura bellezza; infine Henry Moore con la sua astrazione completa attraverso cui stilizzava la figura umana dando vita a opere monumentali.

L’artista laziale Angela Pietropaoli approda all’utilizzo della pietra in maniera completamente diversa dai suoi predecessori perché lei di fatto non è scultrice, e non desidera esserlo, il suo talento inizialmente nascosto e scoperto per pura intuizione è quello di saper ascoltare la voce sottile di sassi che trova durante passeggiate ed escursioni e di cui osserva le forme, lasciandosene conquistare, per poi tirare fuori un’essenza nascosta che esse stesse sembrano suggerirle; il percorso creativo inizia dunque con un ascolto che può durare anche molto tempo, quasi tra lei e le pietre raccolte, già forgiate dall’erosione del vento e del mare e dalle intemperie della natura, si instaurasse un dialogo durante il quale l’autrice comincia a veder fuoriuscire le forme che successivamente diventano la superficie del suo apporto pittorico.

Una volta scoperta l’identità del sasso, Angela Pietropaoli prende in mano i pennelli e dipinge la storia che le è stata raccontata dalla superficie materica o l’identità che ha bisogno di fuoriuscire, mostrando un talento iperrealista acquisito in maniera naturale con una formazione autodidatta che non le ha impedito di cimentarsi con la sperimentazione di diverse tecniche creative come i dipinti a olio, la realizzazione di manufatti con la fusione a cera persa, i lavori in cuoio, per poi giungere alla sua tecnica attuale.

Tutto sembrava essere il preludio di quella che si è poi rivelata essere la realizzazione perfetta della sua inclinazione artistica, quella mescolanza tra ascolto, conseguenza della sua spiccata sensibilità, e il tocco pittorico grazie al quale riesce a dare voce ai sassi che contribuiscono a dare unicità e originalità alla sua arte. Differentemente dagli scultori poc’anzi citati dunque non è lei a dare forma alla pietra, è al contrario la pietra che usando lei come congiunzione tra la propria vita segreta e la possibilità di rivelarsi all’osservatore, ne fa la traduttrice di un’essenza magica che si concretizza divenendo visibile.

L’opera Il leone è viva, tutte le ondulazioni, le rugosità, le striature del sasso sembrano essere lì per esaltare i colori acrilici, mescolati agli acquarelli con cui Angela Pietropaoli lascia emergere, quasi magicamente, il vero volto della superficie, quasi come se fosse già pronta per essere raccontata dal punto di vista giusto; l’Iperrealismo dell’autrice qui diventa talmente vivido da indurre l’osservatore a sentire soggezione davanti allo sguardo intenso del felino, a rimanere immobile immaginando che prima o poi possa muoversi, sbadigliare, o scrutare l’ambiente intorno per lanciarsi in una battuta di caccia. La criniera sembra essere spettinata dalla lieve brezza della savana inducendo a dimenticare di essere davanti a una scultura, o per meglio dire a un dipinto su pietra che ne evidenzia la vitalità e la bellezza.

In Piccolo miracolo il sasso originario sembra essere stato forgiato dall’usura e dall’azione del vento e dell’acqua per assumere magicamente la forma in grado di accogliere il miracolo di una nuova vita, dunque il racconto sottile che Angela Pietropaoli ascolta e poi porta alla luce è quello di un neonato avvolto dal calore di una copertina che lo avvolge, proteggendolo. In questa opera emerge tutta la morbidezza tenera che anche un materiale duro come la pietra è in grado di evocare perché in fondo, nella natura come nella quotidianità, tutto ha un senso differente da quello che appare a un primo sguardo e l’artista diviene così un ponte di congiunzione tra il non visibile e l’inuibile che trova finalmente spazio di manifestarsi. Il pizzo che avvolge il bambino contribuisce a propagare il senso di sofficità che ricorda i regali delle nonne del secolo scorso, quelle memorie di vita che proprio elementi in osservazione silenziosa del trascorrere della vita umana, come le secolari rocce che si incontrano quotidianamente nel cammino, possono riportare alla luce.

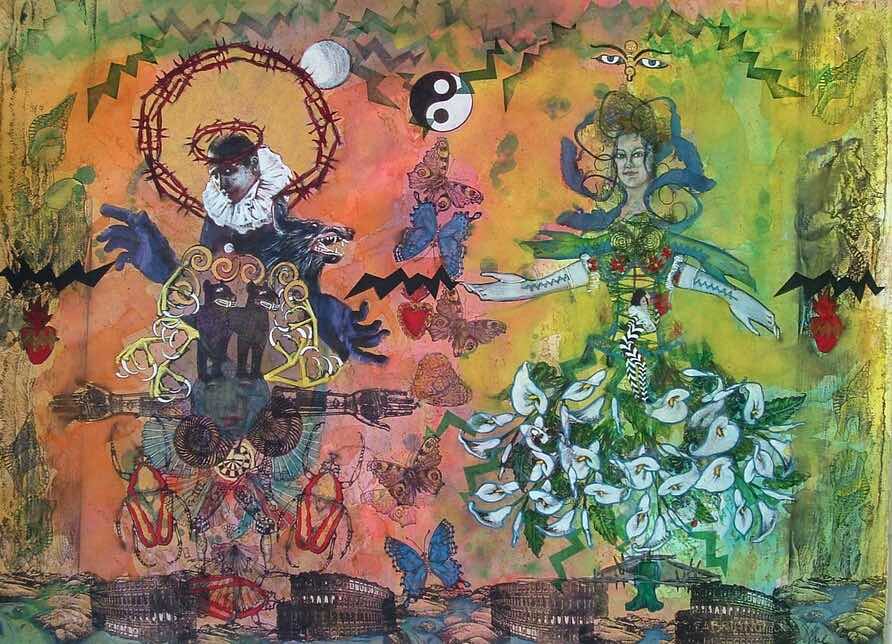

Ne Le maschere Angela Pietropaoli affronta, sotto la guida del sasso, uno dei temi più importanti del vivere moderno, quello del celare la propria vera identità sotto coperture che permettono di mostrarsi al mondo con l’aspetto necessario a sentirsi integrati nella società o semplicemente non vulnerabili; oltre la facciata però esiste un altro lato, quello più autentico forse, oppure un ulteriore strato a protezione di un’essenza che viene svelata solo a chi merita, o a chi ha il coraggio, di abbattere le difese. Osservando con attenzione questo lavoro, può emergere tuttavia anche un’altra chiave di lettura, quella dello yin e dello yang, quell’unione tra maschile e femminile, come suggeriscono le maschere unite tra loro quasi fossero due facce di una stessa medaglia, perché la completezza ha bisogno di due diverse essenze, di un’alternanza emotiva che genera l’evoluzione e l’elevazione della coscienza.

La pietra, i sassi, trovano così con Angela Pietropaoli una nuova vita, introducendo quindi anche il concetto del riuso, della trasformazione degli oggetti in punto focale di un’opera d’arte, senza l’irriverenza del Dadaismo né con la rottura e frammentazione del Nouveau Réalisme, bensì solo con la delicatezza interpretativa e un sentire che si sviluppa dopo un’attenta contemplazione di ogni singolo dettaglio del sasso che si approccia a dipingere, come se la natura più autentica avesse bisogno del suo giusto tempo per manifestarsi. Angela Pietropaoli ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre ed esposizioni, prediligendo eventi che le permettano di essere a stretto contatto con il pubblico, in particolare grazie a l’associazione Cento Pittori via Margutta e l’associazione Art Studio Tre di cui è socia.

ANGELA PIETROPAOLI-CONTATTI

Email: angysstoneart@libero.it

Facebook: www.facebook.com/angysstoneart?locale=it_IT

Instagram: www.instagram.com/angys_stone_art/

The magic of the true voice of stone in the hyperrealist works by Angela Pietropaoli

Very often artists discover their natural talent in an unusual way, sometimes after a long and tortuous path that leads them to feel the need to manifest their interiority through contact with the canvas and colors, in other cases instead, even though the awareness of the creative nature has been clearly manifest for a long time, is reached a revelation that often overturns previous beliefs and allows to tend towards an unexpected evolution which becomes the centre of artistic research, and perhaps also its fulfilment. This was the case with today’s protagonist, who changed the essence of her painting from self-expression to total listening to the stones, which seem to suggest their deepest essence to her, which she then interprets, revealing them to the observer.

The artist’s primordial relationship with rock goes back to distant, prehistoric times, as the tendency to imprint one’s creativity has always belonged to human beings, even when rationality and knowledge did not belong to a condition of life in which instinct predominated over everything; it was precisely thanks to those signs, the graffiti, left inside the caves that it was possible to reconstruct episodes from that distant period, discovering the habits, customs and traditions of populations centuries apart and yet capable, in a rudimentary way, of making art. In the evolution of mankind, it has always been natural stone, thus including marble, that has been the main protagonist in the manifestation of the talent of great sculptors who were called upon to effigy tombs or pay homage to pharaohs, in ancient Egypt, or to recount the deeds of heroes and their moral qualities, in ancient Greece, which gave birth to great authors such as Phidias and Polyclitus; in both great civilisations, stone was used to leave clear and unequivocal messages to the people, as well as to bear witness to the influence of the divine and spirituality in everyday life. It was a fundamental and eternal element to raise the consciousness of the people and to allow everyone, despite the high illiteracy since few were allowed to study, to understand the teachings of the polytheistic religions that influenced and predominated in society.

Going beyond Classicism and advancing through the centuries, there were many sculptors who left great testimonies of their talent by exalting the communicative capacity of natural stone, realising and affirming the importance of art that now also included painting. From the Renaissance to contemporary times, we witnessed the integration of sculpture into architecture, but above all the representation of different epochs and even stylistic languages that were initially linked to traditional figuration, often mixing with religious teachings or representing Christian iconographies, and then slowly evolved to adapt to the epochal changes of the 20th century where marble and stone took on the undefined forms typical of Informal and Abstract Art. Donatello, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Antonio Canova were masters in modelling the hard marble, making it so equal to the human figure that it took one’s breath away, just as Auguste Rodin infused his sculptural works with emotionality and pathos where the material became a means to highlight his existentialist approach to art. Stone was also fundamental in the Dadaist-surrealist path of Jean Arp, in which the renunciation of form was functional to exalt the concept and the theme narrated, sensual or in some cases enigmatic in its pure beauty; finally Henry Moore with his complete abstraction through which he stylised the human figure, giving life to monumental works.

The artist from Lazio, Angela Pietropaoli, approaches the use of stone in a completely different way from her predecessors because she is not in fact a sculptor, nor does she wish to be one. Her talent, initially hidden and discovered by pure intuition, is that of knowing how to listen to the subtle voice of the stones she finds during walks and excursions and whose forms she observes, allowing herself to be conquered by them, and then drawing out a hidden essence that they themselves seem to suggest to her; the creative journey thus begins with a listening process that can last a long time, as if a dialogue were being established between her and the stones she has collected, already forged by the erosion of the wind and sea and the weathering of nature, during which she begins to see the forms that later become the surface of her pictorial contribution. Once she has discovered the identity of the stone, Angela Pietropaoli picks up her brushes and paints the story told to her by the material surface or the identity that needs to come out, displaying a hyperrealist talent acquired in a natural way through self-taught training that has not prevented her from experimenting with different creative techniques such as oil paintings, lost-wax casting, leather work, and then arriving at her current technique.

It all seemed to be a prelude to what turned out to be the perfect realisation of her artistic inclination, that mixture of listening, a consequence of her marked sensitivity, and the painterly touch thanks to which she is able to give voice to the stones that contribute to the uniqueness and originality of her art. Unlike the sculptors just mentioned, therefore, it is not she who gives form to the stone, it is, on the contrary, the stone that, using her as the link between its own secret life and the possibility of revealing itself to the observer, makes her the translator of a magical essence that materialises by becoming visible. The work Il Leone (The Lion) is alive, all the undulations, the roughness, the striations of the stone seem to be there to enhance the acrylic colours, mixed with the watercolours with which Angela Pietropaoli lets emerge the true nature of the surface, almost magically, as if it were ready to be told from the right point of view; the author’s hyperrealism here becomes so vivid that the observer is induced to feel awe before the feline’s intense gaze, to remain motionless, imagining that sooner or later he might move, yawn, or scan the environment around him to launch himself into a hunt. The mane seems to be dishevelled by the gentle breeze of the savannah inducing us to forget that we are in front of a sculpture, or rather a painting on stone that highlights its vitality and beauty.

In Piccolo Miracolo (Little Miracle), the original stone seems to have been forged by wear and tear and the action of wind and water to magically assume the form capable of welcoming the miracle of a new life, thus the subtle tale that Angela Pietropaoli hears and then brings to light is that of a newborn baby wrapped in the warmth of a blanket that envelops it, protecting it. In this artwork emerges all the tender softness that even a hard material such as stone is able to evoke because after all, in nature as in everyday life, everything has a different meaning from what it appears at first glance and the artist thus becomes a bridge connecting the non-visible and the unseen that finally finds space to manifest itself. The lace that wraps the child contributes to propagating the sense of softness reminiscent of grandmothers’ gifts from the last century, those memories of life that precisely those elements in silent observation of the passing of human life, such as the centuries-old rocks one encounters daily on the way, can bring back to light. In Le Maschere (The Masks) Angela Pietropaoli tackles, under the guidance of the stone, one of the most important themes of modern life, that of concealing one’s true identity under coverings that allow one to show oneself to the world with the appearance necessary to feel integrated in society or simply not vulnerable; beyond the facade, however, there is another side, the more authentic one perhaps, or a further layer protecting an essence that is only revealed to those who deserve, or those who have the courage, to break down the defences.

Observing this work carefully, however, another key can also emerge, that of yin and yang, that union between male and female, as suggested by the masks joined together as if they were two sides of the same coin, because completeness needs two different essences, an emotional alternation that generates evolution and the elevation of consciousness. The stone, the rocks, thus find a new life with Angela Pietropaoli, thus also introducing the concept of reuse, of the transformation of objects into the focal point of a work of art, without the irreverence of Dadaism nor with the rupture and fragmentation of Nouveau Réalisme, but only with the delicacy of interpretation and a feeling that develops after careful contemplation of every single detail of the stone that is approached to paint, as if the most authentic nature needed its proper time to manifest itself. Angela Pietropaoli has participated in exhibitions and shows, preferring events that allow her to be in close contact with the public, in particular thanks to the association Cento Pittori via Margutta and the association Art Studio Tre, of which she is a member.